One father-son mule deer hunt through the Arizona desert leads to an unbelievable discovery and a miraculous shot by a young hunter.

It was hard to believe a whole year had passed since last deer season and, as this one approached, I considered it with great excitement tempered with a little sorrow. Dad and I were headed to the small desert crossroads town of Arivaca, Arizona, for the annual youth deer hunt where we looked forward to meeting up with our friends, Scott Mayer and his son, David. We met them in this same camp years ago when my older brother, Brennan, was the one with the tag and I was along for the sport.

Since first meeting in that dusty camp, we’ve all become good friends, burnishing that friendship over the years in the dove fields and deer mountains in the Sonoran Desert of the Southwest. I looked forward to us hunting together again, but this would likely be our last hunt together as both David and Brennan had aged out of the youth camp, Scott was moving to South Carolina and my father was transferring to Utah.

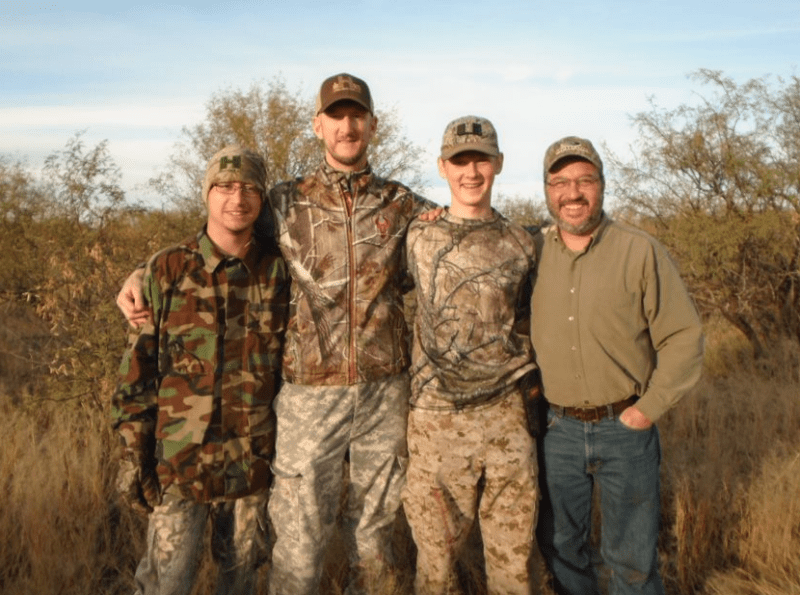

David Mayer, Alan Thompson, Ethan Thompson and Scott Mayer had a successful “last” deer hunt together.

As I’m sure it is in most deer camps, ours was always rich with the kinds of experiences that help forge adults out of young people. There was that year it rained most of the night, filling our tents with water before the temperature plunged so low it encased everything in ice, including us in our sleeping bags. Mind you, this was in the desert where it’s supposed to be hot and dry.

There was the mountain lion a few years back that jumped out of his perch in a mesquite tree landing silently mere feet from us before sleeking away into a wash. Free-range horses nosing tents at night, illegal drug smugglers stealing across the desert, sleepless nights caused by Scott’s epic snoring, rattlesnakes and once, even a black bear track, are just some of the things that made camp interesting and formed the basis for many stories.

Since this was our last hunt, we decided to forego our usual tents and pit toilets in favor of more civilized circumstances. “Two-bedroom house” is what the Airbnb was billed as. The vast turn-of-the-century stucco building in the center of town had once been a hotel. A sign with “Casino Rurál” hung above the thick, solid wood door, and sure enough, when we entered the “two-bedroom house,” found that it was a private casino complete with slot machines, craps table, roulette, formal dining room, banquet room several tables and, of course, two bedrooms.

Friday morning just before dawn, the four of us piled into Scott’s truck and made our way to the main camp where we grabbed a breakfast of egg and potato burritos. We retraced our route along the blacktop road snaking its way through town until we came to a hill near Lake Arivaca where we began the tedious task of glassing for a buck; either mule or Coues deer were on my tag.

Just as the sun was stretching its warming fingers over the horizon and bringing a welcoming orange glow to the otherwise greyscale terrain, my dad located a young Coues buck. It was more than a mile away and courting a couple of uncooperative does, as it was still a little early in the season to be in the mood for any serious romance.

We packed up our gear and scrambled to get closer, but the buck had crossed around the back of a rocky ridge and was gone. Our little group circled the hill to see if we could find him, but the two-point gave us the slip and was back around the other side of the hill. We cat-and-moused him a little, but when we split up to try and keep him on my side for a shot, he and his ladies split the hills altogether.

Though it was only the first morning, my hopes diminished a little when we lost that buck. I had been on this hunt twice before and I knew that, even though there were many deer, shots didn’t come around very often and when they did, they were typically challenging.

Our Airbnb “two-bedroom house” came with slot machines and other gambling equipment.

Getting back in the truck, we drove along dirt roads surrounded by sage brush and mesquite trees looking for another good vantage point from which to glass. Hills loomed up all around, and in the distance past all the hills lay a vast plain.

As the truck continued plodding through the hills and gullies, Scott and my dad found a small outcropping that would allow us to look across a large valley. We pulled over and as we were getting our gear out, sixteen does emerged from a ravine across a hillside about 400 yards away.

I turned around to see Scott signaling that there was a good mule deer buck with them. Grabbing my shooting sticks, binoculars and rifle, I scrambled over to him, heart pounding with excitement.

I never caught a glimpse of the buck. It melted into a thick patch of mesquite and disappeared as desert bucks tend to do.

We waited patiently as the does continued feeding and Scott offered a prayer aloud, while my dad intently glassed the area for any sign of the buck. After several minutes and with the sun starting to descend over the mountain range behind us, the buck came out, feeding with the does on the open hillside.

There isn’t much cover in the desert and when there is, it’s low and thick so shots tend to be on the long range end of things. In this particular camp, most deer are shot between 300 and 400 yards, so I had practiced regularly at 300 yards. We were quickly losing light so closing the distance wasn’t an option. When Dad ranged the buck at 460 yards, I adjusted my scope, sat down and set up for the shot, confident that I could make it.

But I didn’t make a good shot.

I don’t know if it was because of my excitement or the cold breeze that had been blowing for a few hours, but at the shot the buck spun, then trotted downhill toward us, favoring its right rear leg. When he stopped broadside, I shot again but missed clean over his back. Rattled from the first shot, I hadn’t adjusted my scope for the closer shot.

The buck walked into a brushy ravine and out of sight just as the sun was making its departure for the day as well. We quickly established that the best thing to do was to leave the buck alone for the night instead of pushing him in the dark. Our hope was that the leg shot had hit an artery and that he would bed down, bleed out and we’d find him in the morning.

“Hunt with your eyes” is a saying that’s familiar to desert hunters as you spend most of your time glassing for game.

If not, then maybe he would at least be a little stiff and slow moving and we could pick him up again. We marked the spot and drove back to camp with a heavy heart for wounding an animal, hopeful for what the next morning would bring and ended the day together in prayer that we recover the buck if it was dead, or get a clean, broadside shot at it if it was not.

Picking up a sparse blood trail from 460 yards the next morning was no easy feat, but we had left our spotting scope set up looking at where we last saw the buck and Dad and David glassed while Scott and I eased through the mesquite following their hand signals to a small drop of blood. And then another. Small. Specks. Sometimes nothing more than a brownish-red hint on the straw-colored grass that you had to wipe with a wet finger to see if it was really dried blood, or just the color of the grass.

Dad and David joined us as we slowly leapfrogged from one speck of blood to the next for a couple of hundred yards. All told, it took us about an hour to cover that distance. The trail ended in a patch of mesquite where the deer had bedded down and licked his wound until it stopped bleeding, then walked off without leaving any other sign.

Frustrated and disappointed, but confident and relieved the shot was not fatal and the buck would recover, we continued hunting for it in the surrounding area with no luck before heading back to camp for lunch. I scolded myself for blowing the shot, believing I had probably wasted my only chance for success, and on our last hunt together.

We were just getting out of the truck back at camp when Gabe, a retired game warden who helps guide and run the youth camp, let Scott know that a father and daughter team who weren’t hunting was watching a buck that had bedded down for its midday rest. If we were interested in making a stalk, they would show us where it was. Gabe described their location, a curiously familiar one to us as it was one small ridge south of where we had been hunting.

Could it be?

We jumped back in the truck and headed down the road with our spirits and hopes high. A few miles from camp, we went right on the road where earlier in the day we had gone left and quickly found their white truck at the end of the road. Andy Lopez and his 18-year-old daughter, Hunter, allowed us to get behind their scopes and pointed out where to look. We spotted the buck bedded down at the base of an old, black mesquite tree, facing downhill at about 900 yards.

“He’s been chasing those does around and bedding down up there all morning,” said Andy gesturing in the direction of the buck.

My dad and I put a strategy together based on the terrain ahead of us while everyone else stayed back to help give us direction through hand signals. The hunt was on!

Dad and I neared the top of a ridge hoping for some elevation and a clear view of the deer but looked back at our team of spotters who were signaling for us to stop. They signaled that the buck was just above us, a doe was locked in on us and if we moved much more, we would scare him off. Looking in the direction they were signaling, we didn’t see any deer.

We later discovered that their perspective and ours were completely different. In their scopes, it appeared that the deer was right in front of us, but really he was on a hillside beyond.

We snuck around the side of our ridge, keeping a prickly pear cactus in front of us as we made the careful climb to the edge where we could glass and set up for a shot. The doe near the top of the ridge was looking intently in our direction. She knew something was up and, knowing the buck had to be nearby, we scanned all around her and found him bedded to her right with only his head exposed.

I crawled alongside my dad to get set up, using his backpack for a gun rest as I lay prone. Dad got out his rangefinder and whispered, “He’s 395 yards away.” Almost instantly, the buck stood up and looked directly toward us. He didn’t appear spooked like the nearby doe but it was a head-on shot and I decided to wait until the buck was broadside.

The father-son duo made a several-hundred-yard stalk to get close enough for a clean shot on the mule deer buck.

My heart was pounding, and I took some deep breaths to try to calm down. Thoughts raced through my head, and again I had to calm myself. Time seemed to slow down, and the only thing I could hear was the pounding of my heart inside my chest. After what felt like an eternity, the buck turned broadside, and I fired. There was a loud “bang” followed by a “thump” as my round hit the deer directly in the heart. Though dead on his feet, he was still standing so I bolted my gun and fired again with the same accuracy. The buck stumbled backward, collapsing behind the trees and out of our view.

A wave of relief and joy washed over me and filled my entire body with new energy. To say that I was happy would be a huge understatement. I was so excited that I had done what I set out to do and that this time I made a good shot. We looked back to our team and they gave us a touchdown signal.

Dad and I waited for Scott to regroup with us and then headed up together to find my buck while David headed back to camp to bring us some much needed lunch. I was so excited! Luckily, it didn’t take long to find him laying under some brush. I had shot a mule deer, but the antlers looked more like those of a Coues.

It was obvious that the deer Ethan harvested was the same deer he had wounded the day before.

Scott pointed out another interesting thing about this deer— he had a day-old flesh wound on his back leg from a bullet that had torn the skin but not much else.

At first I thought, “How odd. I shot a deer in almost the exact same spot yesterday,” and then I realized the truth. The buck I had wounded the day before and the buck I had killed were one and the same. I was so happy to know that I hadn’t left a wounded deer out in the desert. We tagged the deer, took a few photos and then packed it out.

Looking back on the hunt, there are a few things that stick with me. First, I loved being able to hunt one last time with our close friends. Second, I lost a buck, but because of great people such as Gabe, Andy and Hunter, I got another chance for success. And finally, I think it is incredible that the two deer I shot were actually one and the same—my “miracle mule deer.”

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor, Gordon MacQuarrie and many others. Buy Now