“I decided awhile back that I wouldn’t paint any animal unless I’d seen it first.”

It’s a dangerous trap to fall into, but I’d formed quite a few impressions about Michael Sieve through his paintings long before I ever met him. You hear public figures complaining about this very thing all the time in interviews; the spotlighted actor/artist/musician warning audiences not to search his work for any glimpses into his personality or lifestyle. It’s a legitimate complaint and a better protective device; if I were rich and famous, I’d probably use it constantly. But I had spent a lot of time gazing at the many Sieve prints in our local gallery, even more at the half-frozen in our home, and there were some things about the guy I just felt I knew.

It’s a dangerous trap to fall into, but I’d formed quite a few impressions about Michael Sieve through his paintings long before I ever met him. You hear public figures complaining about this very thing all the time in interviews; the spotlighted actor/artist/musician warning audiences not to search his work for any glimpses into his personality or lifestyle. It’s a legitimate complaint and a better protective device; if I were rich and famous, I’d probably use it constantly. But I had spent a lot of time gazing at the many Sieve prints in our local gallery, even more at the half-frozen in our home, and there were some things about the guy I just felt I knew.

For one thing, it seemed pretty obvious he was a sportsman. That doesn’t make Sieve an aberration among wildlife artists, of course — many of his contemporaries are known to stick a blaze-orange or khaki-clad figure in a scene. But Sieve’s hunters were somehow different. Less obtrusive. Incidental, not central, to the action. As a bowhunter who spends a lot of time up a tree every year, I felt Mike Sieve saw the presence of sportsmen in the woods like I did — tucked away, gazing tensely, watching stuff unfold.

It should go without saying that the animals were good. But there was something different about them as well. When I looked at some of Sieve’s whitetails, for example, I felt, well, nervous. Like they had just winded me, or were about to. Or, if I stayed real still and kept my back against a tree, they might stick around and offer me a shot. There are probably dozens of wildlife artists who can draw an anatomically correct deer. But, and this will sound like an echo from an art-gallery-patron-near-you, few can make them seem like they’re real, breathing critters. I’m not a seasoned enough critic to identify how he pulls it off, but Mike Sieve’s deer transcend the physically correct and enter the land of the living. This guy, I decided, didn’t just watch animals, he saw into them.

It should go without saying that the animals were good. But there was something different about them as well. When I looked at some of Sieve’s whitetails, for example, I felt, well, nervous. Like they had just winded me, or were about to. Or, if I stayed real still and kept my back against a tree, they might stick around and offer me a shot. There are probably dozens of wildlife artists who can draw an anatomically correct deer. But, and this will sound like an echo from an art-gallery-patron-near-you, few can make them seem like they’re real, breathing critters. I’m not a seasoned enough critic to identify how he pulls it off, but Mike Sieve’s deer transcend the physically correct and enter the land of the living. This guy, I decided, didn’t just watch animals, he saw into them.

But the biggest guess I’d made about Sieve’s persona was the hardest to prove by just staring at my favorite prints. I’d developed this feeling about his level of commitment — a kind of craze for perfection and attention to detail that showed up not when I dug into each new print and eagerly gobbled up the image, but when I carefully studied the ones I’d seen for years. I’d find a gamebird tucked away in some corner, barely visible but carefully drawn. A meticulously rendered morel mushroom by a jack-in-the-pulpit in the background. These images went beyond the cutesy can-you-spot-the-whatever-in-this-picture photos that once threatened to saturate sporting magazines. Instead, they showed me an artist who saw wild things as a part of a vital, important landscape; a landscape he was committed to study and depict carefully.

Obviously, this was all a lot of speculation, with a healthy dose of admiration thrown in. I could deduce that he was a careful, thorough hunter, an astute observer of wildlife, and an artist with a bent on excellence, but the only way to be sure was to do the obvious — actually meet the guy. Living only 30 miles apart, this didn’t take much in the way of elaborate arrangements. A phone call to Sieve’s studio near Houston in southeastern Minnesota, and a short chat resulted in directions to the house and an invite to go on an upcoming photo shoot for wild turkeys. Naturally, I accepted.

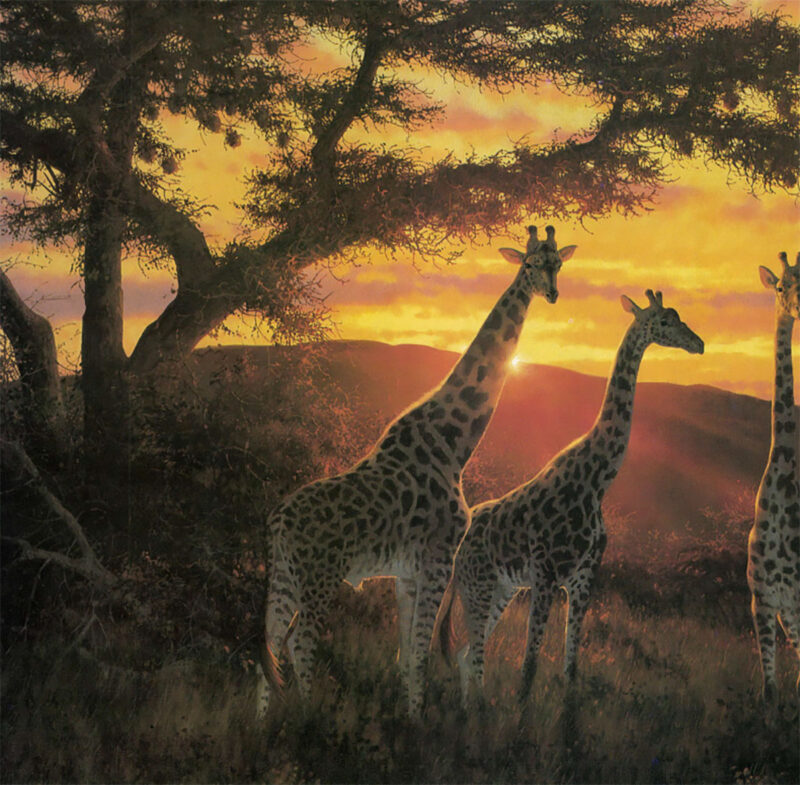

Sand River Sunrise. Sieve painted this captivating portrait of giraffes after watching a particularly beautiful sunrise over the famous river valley in southern Kenya.

My pickup bumped onto the Sieve drive three minutes late for our 5 a.m. date on an April morning. I wasn’t surprised to find him waiting in his truck, camo on and gear ready.

“Did you bring a decoy?” he asked as I slung my gear in with his.

“Sure,” I said, silently congratulating myself for remembering the thing.

“Me too,” was Mike’s reply, as he smiled and pointed to a dark lump near the wheel well. I peered at the object, trying to distinguish a Redi-Hen or Jenny Vane, but was unable to pick out either.

“This is Tammy,” Mike chuckled. I peered again. Tammy purred. A very large, very live domestic turkey, she was wrapped comfortably in a sleeping bag and strapped in a small children’s sled. “We’ll bring your decoy along in case we move very far from the blind I’ve set up, but I think we’ll rely on Tammy for the most part.” Tammy cocked her head and clucked, more soft and pleasant than the sweetest box call.

“Sounds like a good plan to me,” I said.

Half-an-hour later, after walking out on a long, pastured ridge toting gear and dragging Tammy’s sled, Mike and I are crouched in his blind. It is a small, nylon camouflage tent that he has set at field’s edge and covered with netting, grass and branches. I am well-acquainted with the acuity of turkey vision, having had an ambush or two foiled by that line of defense, but Mike has disguised our blind so thoroughly I’m convinced that no bird will ever see it.

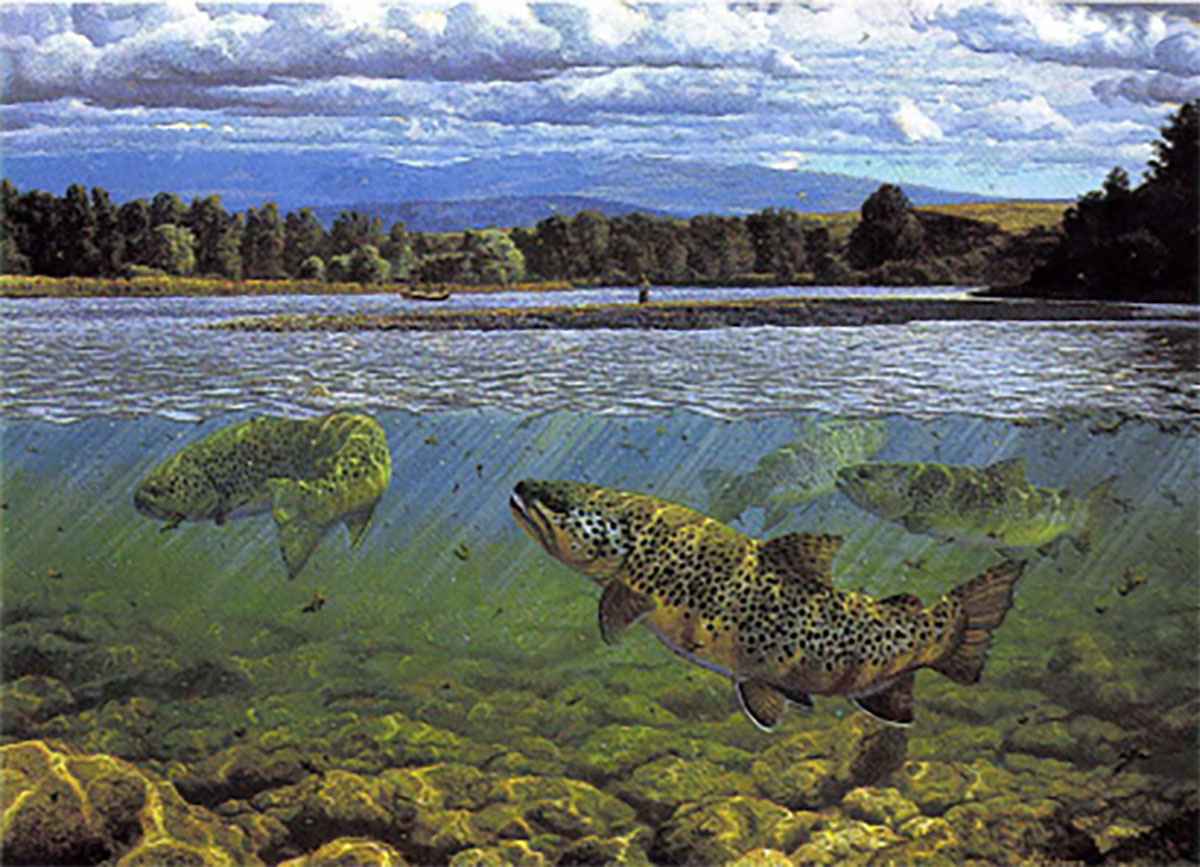

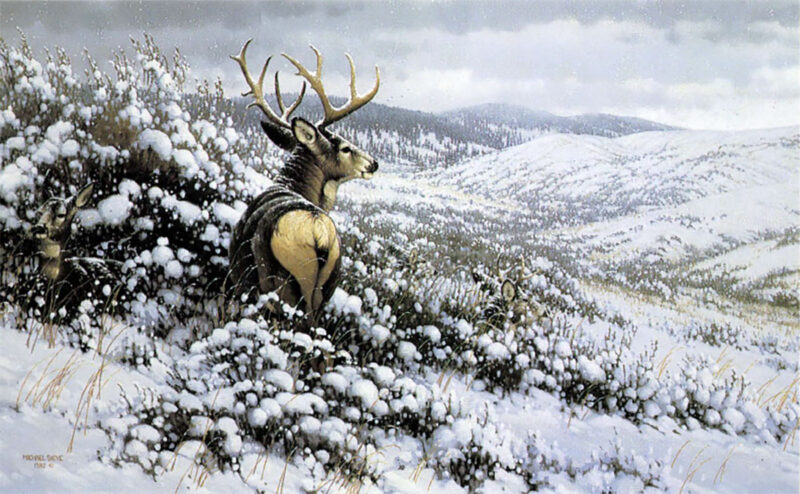

Look carefully or you might miss one of the bucks in White Silence – Mule Deer.

As the sun brings pink light to Minnesota’s bluff country, we hear the first distant gobblers. Mike and I listen intently, trying to wish the birds into our set-up. Should a gobbler show up and offer a compelling courtship drama with Tammy, the scene might actually find itself in the next Mike Sieve painting. It’s common, though local, knowledge that his paintings are the direct result of actual field experiences. His Oak Ridge whitetail series was inspired by a buck fight he saw while bowhunting nearby. The group of bucks in Boys of Summer was a memorable sighting on a mountain bike ride near his home. And, most fitting to the occasion, his popular Chisholm Valley Strut was a recollection from his first successful turkey hunt. Local landowners, hoping their homestead will be the scene in a new Sieve original, have actually called the artist and asked him to hunt their farms.

Suddenly, the soft clucks and purrs of a small group of turkeys join Tammy’s contented babble. Mike leans forward and peers through the viewfinder of his Nikon. I watch his face for signs that the birds have appeared in the powerful lens, but a muted yelp tells me they are hanging back in the woods, unwilling to join Tammy in the sun-warmed field. Minutes pass and their calls fade into the oak and hickory stand behind us. “They must be leaving,” Mike says, eye still to the camera. “She keeps looking back to the woods. Have a look at her.”

Chisholm Valley Strut recalls the artist’s first wild turkey hunt.

He leans back and I press my eye to the camera. Tammy’s image nearly fills the lens. She looks perfect, natural, almost wild to me — but what did the real birds see? What, indeed, did Mike’s trained eye focus on? He was an art major at Minnesota’s Southwest State University where he was schooled in “all types of art.” But Sieve dismisses the importance of any innate ability, even the value of his degree. Later, he’ll tell me “if you give me a person, anyone, who is intelligent, has steady hands and isn’t colorblind, and who is willing to work extremely hard for one year, I can turn them into a wildlife artist.” I am, of course, skeptical, having long ago found myself in the legion of folks who did their best art in coloring books. But Mike Sieve seems certain on this point, and insists research, study and most of all, hard work, are responsible for his success.

When the birds have been out of earshot for an hour, Mike and I are both certain of one fact: the tiny tent is killing us. We crawl out gratefully, stretching cramped leg and back muscles. Mike attempts an apology, but I’ve anticipated this scenario. “Forget it. You know the absolute kiss of death for a hotspot is to show it to a friend,” I say.

He nods and smiles. “I know what you mean.”

On the walk out, with Tammy riding happily behind us and Mike talking about earlier, more successful outings at this spot, it strikes me how elaborate this all is — the carefully concealed and positioned blind, the expensive photo gear, the care and feeding of a tame turkey to hoodwink wild gobblers. Sieve is, after all, a wildlife artist. He could save time gathering reference material on the birds in any number of ways. When I mention this to him, I get an immediate response. “I decided awhile back that I wouldn’t paint any animal unless I’d seen it first,” he says emphatically.

Sieve painted Red Heat – Jaguar after visiting the tropical jungles of Belize in Central America.

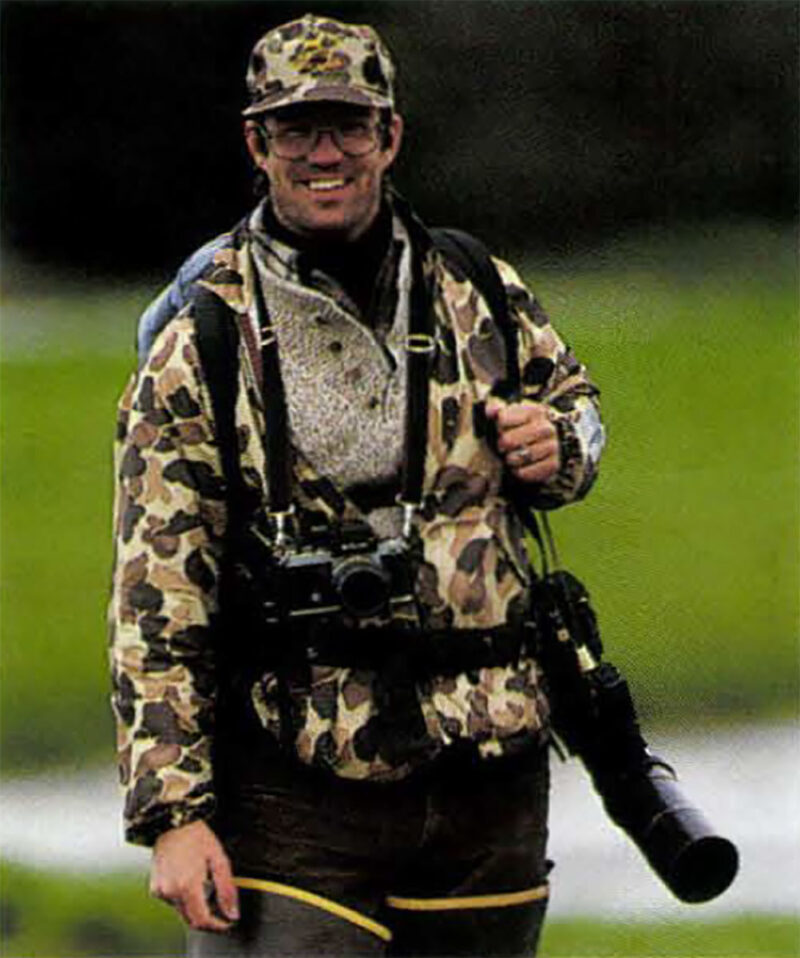

That’s a vow Sieve has taken seriously, and it has resulted in photo expeditions after most wildlife species on this continent and a growing list in others. His Nikon has “taken” brown bears in Alaska, giraffe in Africa, jaguar in South America. Future trips include the Arctic (for musk ox) and the North Pacific (for whales). A professional-quality wildlife photographer, Sieve’s camera work is used only as reference material for his art. He shoots hundreds of rolls of film of wild subjects before he begins an original (he had over 3,000 slides of brown bears in his studio the day of my visit.) and his total photo collection includes over 250,000 wildlife and landscape images.

To build such a library has, of course, taken some effort. Sieve takes “one or two major trips a year and several minor ones” to research and photograph subjects. That effort and devotion is not something all his contemporaries share. “I’ve had one artist tell me he gets most of his research material by taping nature shows on television, and I talked to one guy, who’d just won a state pheasant stamp contest, who didn’t know how to distinguish a juvenile pheasant from an adult.” Sieve laments.

While he is quick to credit his careful wildlife study and photography, Sieve is also grateful for his extensive background in hunting. “I don’t think you have to be a hunter to be a wildlife artist, but I do feel that many of my paintings reflect a real sense of tension, a sense of immediacy and potential explosive action in my subjects. I feel that comes from my hunter’s eye.”

That hunter’s eye, and his artist’s vision, developed as Sieve grew up in western Minnesota. “In that open farm country, you spend a lot of time spotting and stalking, or spotting, then ambushing, animals,” he recalls. “It’s a different kind of challenge, but I’ve stalked close enough to whitetails that I couldn’t draw my bow to shoot them — I was too close. I’ve had friends sneak up and touch deer. That type of hunting really puts you in tune with an animal.”

As a young sportsman, Sieve and his friends spent countless hours hunting deer, predators, pheasants and waterfowl near their homes. But the budding artist realized his native region was about to change drastically. “If the land in southwestern Minnesota hadn’t been decimated, I’d still live there,” he told me. “I’ve seen ponds in the area covered with 10,000- or 20,000 snow geese. Now most of those wetlands have been drained and are used for farm crops. I probably spend as much time thinking about that now as anything. You know; will my son ever see the wildlife numbers I saw in my youth?”

I couldn’t offer him much hope for waterfowl numbers, but it’s a safe bet his son Eric, and twin daughters, Heather and Hannah, will have plenty of wildlife to watch near their home. Mike and wife Deborah Miller moved to the rugged bluff country in 1986 and live in an attractive home that sits on a scenic ridge. Trophy whitetails frequent the nearby hills, and ruffed grouse and turkey densities are among the best in Minnesota. A stone’s throw from their home is his studio, an appealing structure filled with photographs, shed antlers, memorabilia and of course, easels and brushes.

Canadian Gold – Snow Geese, which reflects a lifetime of hunting and photographing geese.

It is here, in this quiet workplace, where Michael Sieve has established his reputation as one of America’s premier wildlife artists. He’s racked up some impressive awards since his debut in 1979 — three Oregon duck stamps, commissions for conservation organizations, “Best of Show” awards at major exhibitions and, most recently, DU’s International Artist of the Year. Sieve acknowledges the prestige of such honors but counts his People’s Choice Awards (voted on by show attendees) as the ones he appreciates most.

“You know, 10 years ago, you could have painted a duck flying upside down with a cigar in his mouth and it would have sold,” he says, recalling wildlife art’s first big growth spurt. “Just the fact that a painting was printed seemed to validate that it was good. Now, people have visited galleries, they’ve been to DU banquets, and they’ve become their own experts.”

Those wildlife art experts are the ones that determine People’s Choice winners, and they’ve been putting their money where their hearts are, too. Over half of his limited edition prints are currently sold out, and despite intense competition from more, and increasingly skilled, colleagues, each new Michael Sieve image seems eagerly snatched from Wild Wings’ galleries. The 41-year-old seems to be enjoying a wave of popularity and success, and I wondered aloud about his goals for the future.

“I’ve seen artists who’ve done a complete turn-around in their subject matter and approach. I don’t see that happening to me.

“I would be happy to keep doing just what I’ve been doing so far. But I do feel that the next whitetail, the next giraffe, the next whatever, has to be the best one that I’ve ever done before I’ll decide to paint it.

“I also want to round out my experience with wildlife species from around the world.

Sieve created Evening Stand – Whitetail Deer for Pope & Young.

“And, I would like to bridge the gap between non-hunters and hunters. I feel that I have my feet solidly in both camps — I’ve found myself at campfires with photography friends where I’m sounding like Joe Kill-‘Em All, and I’ve shared fires with hunting buddies and come off sounding like a preservationist. I’d like to bring reason to both groups.”

That goal, though admittedly important, seems too remote, too difficult and I tried to dismiss it as our conversation stretches into the afternoon. But later, when I’m capping my pen and getting ready to leave, I glance at a print hanging in Sieve’s studio. In it, a carefully drawn whitetail buck leaves the safety of a woodlot to sprint across a field. In the background, part, but not the focus, of the action is the shadow of a hunter in a treestand. Deer and man are overpowered by an orange-red setting sun. It’s not a print I own, and one I’ve never really studied. But if there is one thing I’ve learned since I’ve met Michael Sieve, it’s that his paintings do reflect his personality — his love for wildlife, his passion for hard work and attention to detail, and yes, his hunter’s eye. If those people who enjoy wild places and the creatures who inhabit them can rally around anyone, someone like Mike Sieve just might be the guy.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1992 September/October issue of Sporting Classics.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now