“He’s gone!” Mack cried. Hurled from the canoe, Evans had vanished in the ensuing violence.

Paul Templer had seen Evans’ distress. He spun his canoe about. He’d almost reached his friend when a “bow wave” rushed toward him, an underwater beast of great size. He slapped the water with his paddle to turn it, and stretched to grab Evans. “Our fingers almost touched.” Then his world exploded.

The morning had started routinely. Paul, age 28, was standing in for another tour guide laid up with malaria. Each of three canoes carried a guide and two clients as they started down the Zambezi, Africa’s fourth-longest river. Skirting a small pod of hippos, Paul slowed in backwater to let the rear-most craft, trailing a kayak, catch up.

That’s when Evans’ canoe flipped skyward, as if blasted by a submerged mine. Passengers and gear were flung into the Zambezi. As Mack pulled the clients into his canoe, Templer was reaching for Evans—a union severed by an eruption that jerked Paul into the river. He lost his bearings. “Below my waist, I could feel the cool river water. But my upper body was warm. Oddly, it was wet too. There was great pressure on my lower back. I tried to move and couldn’t.”

Paul was halfway down a hippo’s throat. Instantly he knew he might well die here, soon.

But the beast must have choked, for it spat him out. Paul caught sight of Evans and lunged toward him. Then he was hit again, from below. The hippo engulfed his legs in a crushing grip.

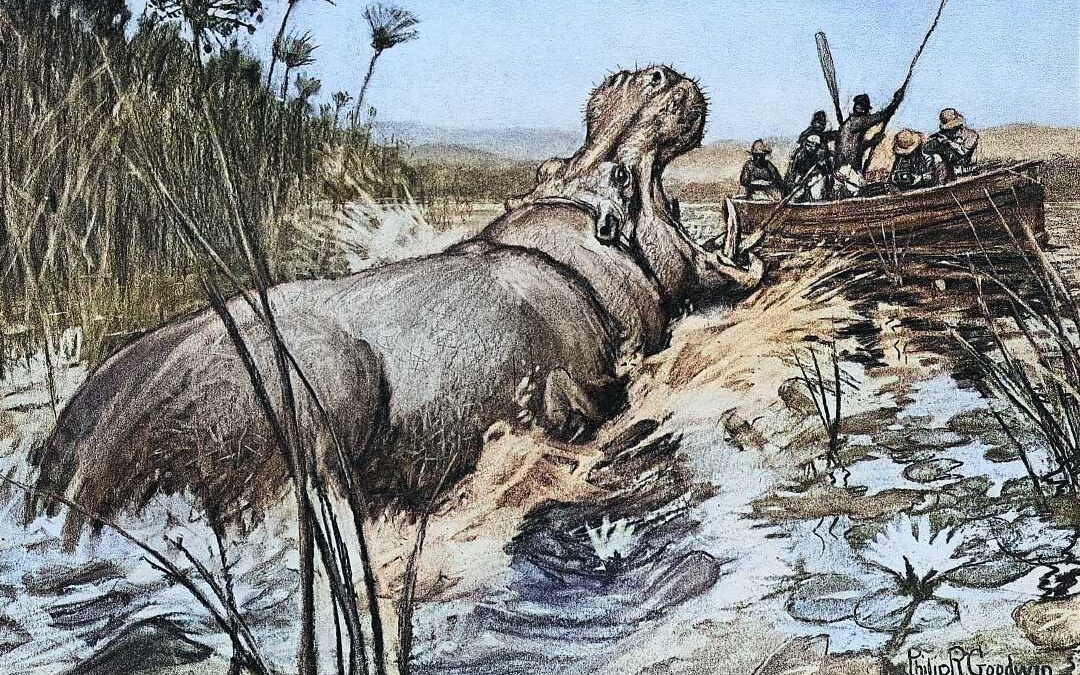

Expelled a second time, Paul looked around frantically for Evans. Then he struck out for shore as fast as he could swim. Mid-stroke, he saw the hippo come up behind, “mouth wide open.” It grabbed him sideways, at the waist, and “went berserk,” as hippos do in fights that maim three-ton opponents. Templer amounted to no more than a rag. A hippo’s thick, tusk-like canines can grow to great length, in jaws that open 150 degrees to span three feet. They exert triple the force of a lion’s. One bite can cut a man in half.

Bloodied and in shock, one arm pulped, Paul had the presence of mind to gulp air at the surface and clutch the tusks to avoid being shredded as the creature submerged. “Meanwhile, at great personal risk, Mack paddled the kayak through the surf alongside us. As the beast rose again, he grabbed my hand. I managed to grip the kayak.”

Mack muscled the craft to a mid-river rock. Templer had a big hole in his back. Mack plugged it with Saran Wrap. The first aid kit was gone as were the group’s rifle and radio. And Evans. Blood bubbled from Paul’s mouth: a punctured lung. With one paddle for the two remaining canoes, guides and clients made for shore. Long minutes later, they reached a vehicle. A hospital was eight hours away.

Paul’s left arm was beyond saving; but several surgeries would repair the other damage.

Evans’ body would turn up in the river, unmarked. He had drowned.

The hippopotamus (from Greek for “river horse”) shares rivers, reed-beds and shore-line pastures with swamp-dwelling antelopes such as sitatunga and red lechwe. On hot days, hippos keep cool and protect their skin from the sun in the shade of nearby bush. Or they lie mostly submerged in sloughs. Lazily slipping under water, a hippo lets its bum sink, to descend at an angle, head up. To enter water fast or to submerge quickly, it makes for the bottom nose-first.

Hippos can swim at 10 knots but prefer to run on river bottoms. They can submerge for more than six minutes, their bulk no barrier to ballet-like moves below the surface. In narrow channels, territorial hippos pose a hazard to small boats. Stout legs and big, webbed, four-toed feet propel these creatures at up to 25 mph for short sprints on land.

Villagers take care to avoid hippos during their nocturnal trips ashore. A hippo is faster off the blocks and quicker in the turns than its bulk suggests. Accidentally getting between a hippo and water, or a hippo cow and its young in the dark, has little to recommend it. But hippos don’t kill to eat. Fourteen pairs of molars and premolars grind 250 pounds of greenery daily. A hippo clips grass close with strong lips. Two pairs of central incisors in either jaw complement the tusks (canines). If a tusk breaks, the tusk opposite can grow to 30 inches. During mating brawls and territorial tiffs, these forward teeth, all of hard ivory, leave bulls badly scarred, occasionally with fatal wounds.

Hippo bulls mark their territories by scattering dung with a switching tail as they defecate. They live on the fringe of the family unit or crèche, a matriarchy that can number more than 30 cows and calves. The cows tolerate no intrusions, attacking with equal vigor bulls and boats that stray too close to their young. Before bulls reach sexual maturity at age five, they’re driven from the crèche.

The hippo figures heavily in native lore. Bagoma fishermen on Lake Tanganyika told the Belgian explorer Jean-Pierre Hallet that hippos bump boats to honor an ancient agreement. “Mamba (Swahili for crocodile) made a treaty with Kiboko (the hippo). ‘I’ll permit you to graze the shore if you’ll overturn the fishermen’s canoes so I can eat.’ Kiboko consented.” Less entertaining logic for a hippo-hull collision: the boat came too close to a calf or accidentally struck a surfacing hippo. It’s been suggested that small craft may be mistaken by submerged hippos for crocodiles, which aren’t welcome in hippo crèches. Incidental contact with a resting hippo typically sends the animal in a dive for the bottom.

Early European explorers had little good to say about kiboko. It destroyed boats, muddied pools and sometimes killed hapless natives and livestock. Adventurer Samuel Baker reported seeing a panicked hippo attack the floats of a paddle-wheel steamer on the White Nile, breaking several.

Hippos can still be a nuisance. They pound deep trails into pastures and chomp through gardens with exasperating efficiently. Their dung is no selling point for suburban real estate—and where they’re not shot, hippos blithely graze neighborhoods after dark. On the shores of Lake Victoria, hippos nightly pocked the greens of Uganda’s Jinja golf course. Frustrated staff eventually ruled that balls landing in a hippo footprint could be hit from adjacent turf with no penalty!

On Zimbabwe’s Lake Kariba, a lodge owner decided that a hippo grazing on the grounds was bad for business. As luck would have it, I was hunting buffalo nearby with a colleague who wanted to shoot a hippo. We scouted by sitting on a picnic table one evening as the beast emerged from the lake and trotted up to the lodge’s green grass apron, walking within feet of client cabins. At its next appearance, my friend opened up with his .416 from behind a veranda. I heard at least three 400-grain solids strike ribs. The bull ran off into the lake. A long rope and a tractor helped with the retrieval the next morning, after he’d surfaced.

Another hippo I saw shot was in a properly wild place: a pool surrounded by thick brush with the look of buffalo cover. Hippo spoor from pool to bush and back indicated this was a big bull. Jamy Traut, Janice’s PH, said her best bet would be an ambush the next day, “when he comes out to feed.”

We parked the Cruiser well away from the pool in mid-afternoon. To our surprise—and chagrin—we had barely begun our approach when the hippo slipped into the water on its far side. A blazing sun had pulled it early from the bush. Now it was cooling off where it might stay until dark. “Recovery is easier when they’re not in the water,” Jamy sighed. “But let’s try to make this work.” He led, bending low, then crawling through cover to reach a kopje near the shore. Blessedly, the hippo’s head was not only visible, but carving a wake toward us at 40 yards! Jamy raised the sticks. Janice eased her Ruger over them and peered through the 1.5-5×20 Leupold. At the .375’s blast, the bull submerged. We would have to wait to confirm the effect of her 300-grain TSX.

A hippo that has fed recently will surface sooner than one with an empty gut. Expanding gas lifts the carcass slowly into view. Janice’s bull rose in just over an hour. After snaking the Land Cruiser close to shore, the experienced crew waded out with a tow strap, then winched the hippo in until friction in the shallows braked it. Then a group of able natives drawn to the site by the rifle’s blast waded into the pool, braced shoulders against the beast and, with collective heave-hos, rolled it to water’s edge for butchering.

Hippo meat makes good table fare. The lard (200 pounds on a big bull) is likewise valued. Hippo hide is traditionally dried in strips, then, in southern Africa, hammered into whips called sjamboks.

Mamba Crocs

From his camp on a branch of the Tana River late in 1894, ivory hunter Arthur Neumann trekked to the southeast corner of Lake Rudolph where he fought challenging terrain and cold wind. Persevering, he shot two elephants whose four tusks averaged more than 110 pounds! But his luck was about to change.

On New Years Day, 1896, his servant, Shebame, was snatched at river’s edge by a huge crocodile. That afternoon, after his .303 misfired, Neumann failed to out-run an elephant cow and barely survived a pummeling. Bedridden with crushed ribs, he was nursed back to health by his staff on a milk diet.

While crocodiles and elephants rank near the top of any roster of Africa’s most dangerous beasts, the Nile crocodile, like the hippo, is chronically under-rated. Credit their habitat. Unless witnessed, then reported, people killed in the water vanish without record. Also, most victims are villagers—not visiting hunters whose misadventures with elephants, buffalo, lions and leopards are headline news.

Recent estimates of people killed every year by animals in African waters range widely: 300 to 1,000 for crocs, 500 to 3,000 for hippos. Numbers for deaths caused by the “Big Five” are almost census-solid: 500 for elephants, 200 each for buffalo and lions. Leopards aren’t as benign as low fatality counts suggest. “About 80 percent of animal-caused injuries to hunters in Zimbabwe are from leopards,” one PH told me. “Most happen during follow-ups of wounded cats waiting to shred everyone in the party. Given prompt medical attention, though, the wounds are seldom fatal.” He added that elephants cause 80 percent of human deaths attributed to Zim’s wildlife.

The size of hippos and crocs, their great jaws, and the water that renders victims all but helpless if it doesn’t drown them, makes these creatures particularly lethal.

Unlike the vegan hippo, the crocodile views humans not just as a threat, but as food. This antediluvian predator hunts at water’s edge, which draws all manner of prey. Women washing laundry wade, then turn their backs on the deep to beat laundry on rocks. Children frolic in shallows. A croc can lie submerged for up to an hour. Eyes still as a lily pad above the surface are dismissed at a glance as flotsam. A crocodile can approach so slowly as to appear motionless. Attacks are seldom premature; the beast is almost always within certain reach of its target when it rockets ahead to kill. Its muscular tail is both engine and rudder. It can also bludgeon big antelopes off their feet.

Jean-Pierre Hallet, who after WW II spent years studying people and animals of the Congo, wrote that the Nile crocodile is a “paradox and a miracle,” a creature with many handicaps “half-crippled by his own anatomy.” Cursed with bony ribs on cervical vertebrae, “he cannot turn his head to seize a man [or] chew [him] with his huge battery of teeth or gulp [him] down his narrow gullet.”

While a crocodile’s upper jaw closes with tremendous force, exerting pressure of up to 5,000 psi (compared to 100 for a human’s bite), this animal can’t move its lower jaw. Only the upper is hinged, and muscles that open it are weak. Even a big croc can be muzzled with a length of twine. The tongue is also immobile; it’s unable to manipulate food.

Long ranks of thick, hollow, separately socketed teeth give prey little chance to escape a croc’s grip. Those teeth, by the way, are useless for aging, because they’re replaced as needed over a lifespan that can exceed 70 years. An old bull may have grown 8,000 teeth!

Seizing an animal, a croc typically drags it into water and, submerging, drowns it, dismembering big prey by grabbing appendages and twisting them free. Stubborn carcasses may be lodged in underwater debris until they become soft enough to gulp in pieces. Swallowing is usually done at the surface.

Once, while hunting along the Zambezi, I was almost upended by a crocodile that blasted through reeds to gain the safety of the water. When it surfaced to look back, its eyes seemed a foot apart! My pulse may have skewed that measure. But croc attacks farther than a lunge from water are rare. A 20-knot swimmer, a croc is only half that fast on land. It can’t easily kill or eat there. It’s aware it has few defenses against heavy bush-dwelling beasts that are also quick and agile. Its legs aren’t suited to chasing or escaping.

Hallet once saw a big crocodile grab a cow elephant by the trunk as she extended it to drink. She endured what must have been terrific pain to tug the 1,500-pound lizard ashore where she pounded it to pulp. C.S. Stokes wrote of another crocodile-elephant tussle. The croc wound up in a tree.

On October 24, 1955, Lake Tanganyika tested Hallet’s knowledge of crocs—and his will. From a pirogue with Bagoma fishermen 100 yards off-shore, he was using gelatin explosive to gather herring-like ndagala for people in drought-stricken Burundi. Then a fuse failed. Hallet saw the Bickford cord light up and hurled the charge—but too late. The blast blew off his right hand and threw him into the croc-infested water. His helpers, wanting nothing to do with a white man’s death, paddled off at once.

Ears ringing and partially blinded, Hallet made out two “scaly backs carving a wrinkled wake” toward him. He pressed his bleeding stump to his side, then kicked and pulled furiously with his good arm toward shore. Seven more crocs homed in like torpedoes. One was “almost as large as a native dugout…. I heard [its] jaws snapping shut. Another clack sounded [and] I felt a crocodile pass behind me, his scutes scraping my back….”

Terrified and losing blood fast, the six-foot-five Belgian forced himself to abandon his crawl for a slower, more upright dogpaddle. “A vertical target is not easily snatched by jaws designed to operate in one plane on horizontal prey,” he told me years later—when he defended the crocodile as a wild creature with only natural cravings. “It has no grudge against humans. It responds to hunger. As do we all.”

Safari operators bait crocodiles with meat hung over water or secured on the shore near sandbars and other places they might “lie up” exposed. Crocodiles move most actively at night, aided by rhodopsin on their retinas. It glows yellow in a torch beam. Most shooting is from blinds near bait at dawn and dusk.

“We must bait where crocs feel safe,” explained Jamy Traut as we motored up the Kwando River, which threads elephant-tall reeds in northern Namibia. “Old crocodiles are sensitive to disturbance. They often lie up unseen where they can monitor the bait.” We beached well shy of a post on a garage-size sand apron fronting a slough. We sneaked forward to the post where a big chunk of wildebeest meat was wired at shin height. Our tracker added meat higher on the post. “The height a crocodile’s reach helps us gauge its size. Torn bait at waist height is promising. Tooth furrows above that get our attention.” Jamy reset a trail camera and indicated a spot 70 yards across the pool. “I’ll sit with a client there.”

Heavy hippo traffic may have limited croc action on that section of the Kwando during my visit. One of Traut’s clients later shot a 16-foot croc, a very old, very heavy beast.

PHs tell me accurate shooting is the key to killing and retrieving crocodiles. No need for big-bore power; a 308 Winchester or 30-06 is enough. But the first bullet must anchor the beast. From the front or behind, say the experts, “center the skull. From the side, aim just above the tip of the smile.” Muff the first shot, and you’ve missed your chance. If the croc can move, it will reach water faster than most hunters can send an aimed follow-up. The odds of finding and retrieving a croc that dies under water are slim.

Even when plentiful and confined to watercourses shrunk by drought, crocodiles can be elusive. Shot early on as dangerous vermin, later for their hides and as trophy game, crocs have endured hunting since before colonial times. Conservationists, too, have targeted them. “I avow, with what regrets may be necessary,” wrote Winston Churchill, “[a] hatred of these brutes, and a desire to kill them….” Theodore Roosevelt boasted he “always shot crocodiles” when he had the chance.

Crocs have been used by native peoples who accept their depredations with stoic shrugs. In 1874, while returning from a hunting trip on the Chobi, F.C. Selous met a trader just back from Sesheki, known for its especially aggressive crocodiles. At that time, wrote Selous, “many people were executed for witchcraft and other offenses, and their bodies thrown to the crocodiles….” The trader told him that one day as he drank beer with Sepopo, king of the tribe, a beggar interrupted. Sepopo observed he was a very old man—could he do any work? Informed that he was too old to work and dependent on charity, the potentate said: “Take him to the river and hold his head under water.” The beggar was led off by a steward, who returned shortly. “Is he dead?” asked Sepopo. The man nodded. “Then give him to the crocodiles,” said the king, and turned back to his beer.

The behavior of Africa’s most feared beasts is not always hard to explain.

This article originally appeared in the 2024 Sporting Classics July/August issue.