In all of art history, never has there been a more venerable emblem of wildlife conservation than the tiny U.S. Federal Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp.

Invented by an American sportsman during the Dust Bowl to protect habitat for migratory birds, revenue generated through Duck Stamp sales has been instrumental in safeguarding 5.7 million acres of wetlands, in turn benefiting hundreds of species and helping to create or expand more than 300 national wildlife refuges.

Until 2016, one master painter hovered above all the rest in the long history of the duck stamp art competition. Maynard Reece, a Quaker minister’s son from Arnolds Park, Iowa, near the shore of Lake Okoboji, had his name on more Federal Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamps than any other. Reece’s mark stood for nearly a half-century, equaled only in recent years when James Hautman, the phenomenon from Minnesota, triumphed with his fifth—a portrayal of three Canada geese that appeared on the 2017-’18 stamp.

While Hautman is an undisputed superstar still in the prime of his painting years, his legend doesn’t come close to rivaling Reece, whose career reaches back deep into America’s golden age of sporting art, when, notably, there were twice as many duck hunters as today.

Not only was the competition fierce, but given hunting’s more prominent profile in society, earning the top prize offered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was arguably more prestigious.

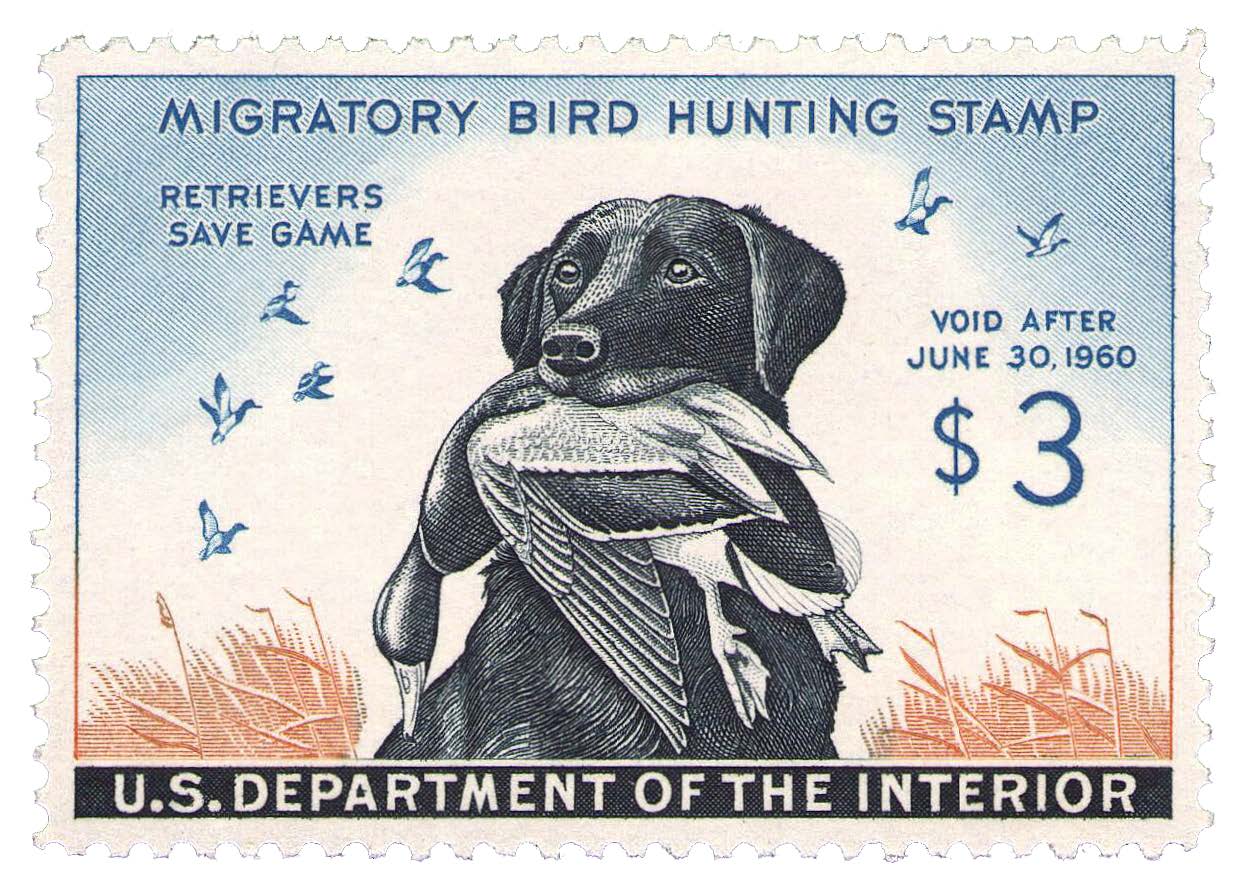

Reece’s 1959-60 Duck Stamp marked the first time for an animal other than duck or goose to appear on the Federal stamp.

Consider this: Reece won his first federal stamp contest as a 28-year-old in 1948, his second in 1951, third in 1959, fourth in 1969 and the last one in 1971.

The visibility of his art made him a revered figure to generations of waterfowlers, and his Duck Stamp dominance gave him mystique, leading us now to this question: Whatever happened to Maynard Reece?

The good news is that Reece celebrated his 99th birthday in April. When I reached him by phone in Des Moines some 20 years after the last time we spoke, he was as chipper and clear-headed as ever.

Despite the distraction of a hospital visit, he was indefatigable in spirit, back at the easel completing a commission of flying goldeneyes. Sharing the kind of detailed information that the late famed ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson—a friend of Reece’s—might have imparted in his bird guides, Maynard, off the top of his head, held forth with a near-poetic oratory on the life history of these beautifully plumed ducks.

And you could hear emotion quivering in the old sage’s voice.

Untold thousands of Americans have Reece’s art on their walls, be they coveted originals, limited-edition prints or any one of the dozen or so collectible wildlife stamps he created.

“For people of late Baby Boomer age and older, Maynard is considered one of the true greats of sporting art,” said Dr. Burt Brent, a wildlife sculptor, world-renowned children’s surgeon and close family friend. Brent’s encouragement, in fact, is one of the reasons that Reece’s eldest son, Mark, went into medicine. A second son, Brad, ran the Maynard Reece Gallery in Des Moines for 35 years.

Reece’s Jumping Whitetails as seen at Cisco Gallery in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

“I’ve known Maynard and his family a long time, and there’s no one else in wildlife art like him out there,” Brent said. “He’s outlasted all of his very talented peers.”

In 1988, McCall’s magazine called Reece “the dean of American waterfowl painters.” The release of a limited-edition print commissioned to raise money for wildlife habitat once earned him an invitation to meet with President Ronald Reagan. At that event, Reece’s wife, June, was initially denied access. Only after she pulled out the 1983 Arkansas Duck Stamp and said, “My husband painted this, and he’s here to meet the President,” was she allowed to pass by security guards, who were mightily impressed.

Decades ago, Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, honored Reece as a “master bird artist, joining a distinguished who’s-who pantheon of other bird painters.”

“If you look at Maynard’s portfolio, you quickly realize he’s had a feel for capturing classic scenes that resonate with hunters, including portrayals of fish and big game,” Brent said. “But the thing he’ll always be especially noted for, of course, are his depictions of waterfowl.”

Born in 1920, Maynard Reece had a natural talent for drawing, first working for the Iowa Department of History and Archives. Serving in England during World War II and displaying his artistic talent then, he forged lasting friendships on the other side of the Atlantic.

Brent recalls one Christmas spent with the Reece clan. When the Brents mentioned they were going to Scotland, Maynard recommended people they had to meet.

“The people he introduced us to were avid naturalists living on eight square miles of land in a manor house that looked like a castle,” Brent said. “They had some serious art—works by Renoir and Pierre Bonnard—and hanging nearby was an original Reece.”

Reece literally hunted and fished his way to excellence behind the easel, insisting that every moment he spent over decoys in a blind, skirting cornrows in search of ringnecks or casting a line helped him breathe more authenticity into his work. He believed great artists needed to hold nature in their hands, rubbing up against its texture, absorbing the elements with their senses and watching ducks rise or land during the glowing hours around dawn and dusk.

Reece painted this trio of mallards for the First of State Iowa Duck Stamp and print.

The Saturday Evening Post once called and wanted him to paint a trophy-size trout for a two-page spread.

“I said, ‘I’ll try to do it, but I need to find a ten-pound trout,’”Reece noted.

“The art director replied, ‘Can’t you just use a little one and make it bigger?’ “To which I said, ‘Sorry, it doesn’t work that way.’”

Reece refused to fake it. He wanted to be true to his subject, an ethic taught to him by his most influential mentor. He didn’t merely follow in the footsteps of Des Moines newspaper cartoonist Jay “Ding” Darling, who initiated the Duck Stamp concept and had his own artwork appear on the inaugural stamp in 1934. (Darling, it must be noted, won two Pulitzer prizes for editorial cartooning and founded the National Wildlife Federation in 1936.)

“Ding had vision. Right in front of us, in Iowa and everywhere else, we were seeing so many wetlands being drained and turned to crops or covered over with development,” Reece said. “Natural habitat for birds was being lost so fast, and nobody seemed to be caring. The advent of the Duck Stamp enabled the country to kind of reverse course. I was just honored to be part of it.”

When Reece was 18 years old, he first showed Darling his drawings and received a no-holds-barred critique. It was the young artist’s humble response, vowing to work harder and get better, that earned Darling’s respect and a friendship that lasted for two decades.

Over the Marsh Canada Geese by Maynard Reece. Courtesy Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum.

Reece’s talent eventually catapulted him to fame with Duck Stamps, and it brought illustration jobs for magazines ranging from Sports Illustrated and The Post to Outdoor Life, Sports Afield and Ducks Unlimited, among others. Along the way, he became friends with fellow Duck Stamp winners Frances Lee Jaques, most famous for painting dioramas for the American Museum of Natural History in New York and Lynn Bogue Hunt, the heralded outdoorsman and illustrator.

Reece told me his favorite Duck Stamp was the 1959 portrayal of King Buck, the near-mythical black Labrador, holding a mallard in his mouth. The champion dog was owned by John Olin, who created Winchester’s Super-X shotshell and founded Nilo Kennels. He filled a sketchbook of drawings showing King Buck from many different angles until he got it right.

When I asked Reece about his most satisfying achievements, he put his friendship with Darling, visiting Jacques in New York City, and his cabin in Minnesota at the top of the list. For decades the Reece clan spent summers in Minnesota at a lake place in the North Woods between Grand Rapids and International Falls.

“When I started it was a bold notion to believe you could actually make a living as a wildlife artist, but Ding encouraged me to stay with it,” Reece said, noting that he adhered to an annual ritual of showing Darling his paintings.

In 1959, when Reece built a new house and studio, the Des Moines Register featured a full-page story about “The House That Birds Built,” a reference to the windfall Reece enjoyed from painting the Duck Stamp.

“Ding called me up and said, ‘I want to see this house of yours,’” Reece said, noting that Darling was in declining health. Doctors told Darling he shouldn’t climb stairs, but he insisted on exploring all of Reece’s digs.

“I gave him a painting, and halfway through our conversation he winked and said, ‘Maynard, I’m sorry. I can’t help you anymore, but don’t stop coming to see me.’” Less than three years later, Darling died at age 85.

“You could say that Ding Darling changed the course of my life, and he benefited the lives of millions of hunters,” Reece said. “His conceiving of the Duck Stamp idea when he served on a presidential commission created by Franklin Roosevelt was ingenious, but it was such a necessary thing that all of us should be grateful.”

Maynard Reece insists that America’s future be forged by conservation.

“As hunters, we need to remain vigilant in defending habitat because there aren’t as many of us around as there used to be and human population pressures are greater than ever,” he said.

What is Maynard Reece’s next goal? If he were a younger man, he might consider coming out of retirement and giving Jimmy Hautman a run for his money.

“My boys tell me I ought to aim for 100. It would be a nice feat to reach,” he said.

In fact, Reece has already reached the sky. His Duck Stamps are a part of art history, and the wildlife habitat they’ve helped to secure for future generations is eternal.

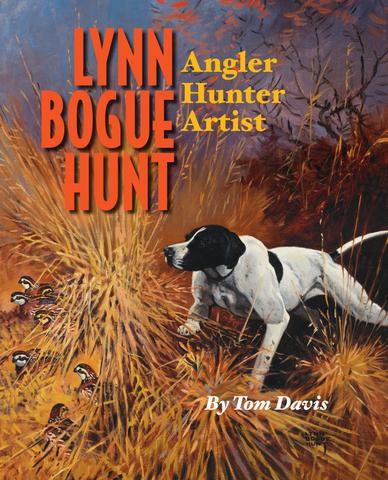

Acclaimed wildlife artist Lynn Bogue Hunt, who illustrated more national magazine covers than any other artist in history, is the focus of a beautiful new coffee-table book from Sporting Classics.

Angler, hunter, and artist, Lynn Bogue Hunt was America’s most popular and prolific outdoor illustrator of the mid-20th century—the “Golden Age” of the American outdoors. He painted a record 106 covers for Field & Stream; illustrated dozens of books on waterfowling, upland bird hunting, and saltwater fishing; designed the 1939-’40 Federal Duck Stamp; and was described by his friend Ernest Hemingway as “the finest painter of game birds that we have in America.”

Lynn Bogue Hunt—Angler, Hunter, Artist showcases the complete collection of Hunt paintings acquired by New Jersey sportsman Paul Vartanian. Not only is it the world’s largest collection of Hunt paintings, drawings, and memorabilia, but the largest and most complete collection of the work of any major sporting artist.