In the end, the best sporting artists are skilled translators of ideas.

Years ago, my husband Charlie and I were rummaging through a barn full of “antiques” in southern Ontario when he pulled a framed upland shooting print out of a corner. “How much?” Charlie asked the dealer.

“If it was a Bateman, I could get three or four hundred,” the man replied, squinting at it. “You can have that one for $75.”

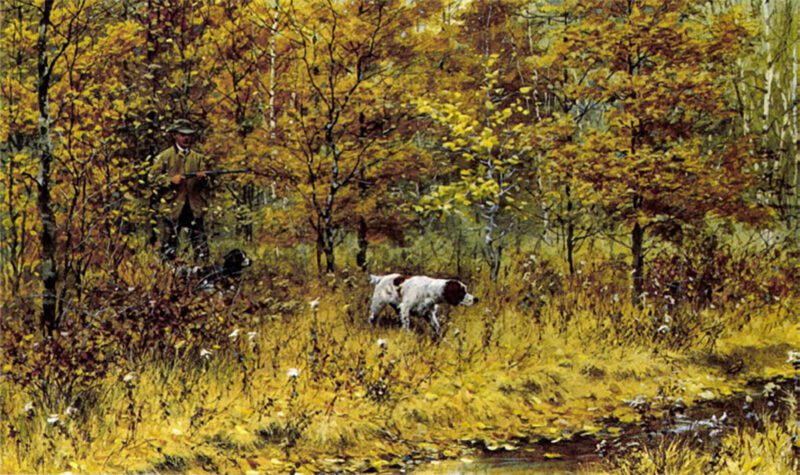

I wrote the check and Charlie took home a signed artist’s proof of A. Lassell Ripley’s After Grouse, painted in 1949. Ripley considered grouse hunting the epitome of sport, and this sensitive rendering of two hunters, two setters, and two birds communicated that passion. Still in its original frame with an Abercrombie & Fitch label on the back, the print was probably worth about $1,500.

Charlie buys what he likes, but he also has a good eye for a good painting. He does his homework, and he knows his artists. In the case of upland hunting art, it’s fairly easy to name the choice painters, past and present, because there are so few of them. This article looks at the best of yesterday along with a trio of present-day painters and why they lead the pack.

A. Lassell Ripley was one of a handful of past masters of upland shooting art in this country that includes A.B. Frost, Lynn Bogue Hunt, William Harnden Foster, and Ogden Pleissner. All of them Easterners, all of them gunners, they knew what upland hunting and autumn were all about. They painted hunters and bird dogs and upland game from firsthand experience distilled through years afield.

The progenitor of this legendary lot was A.B. (Arthur Burdett) Frost (1851-1928), who painted for the magazines and illustrated nearly a hundred books for numerous well-known authors including Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens, Joel Chandler Harris, Theodore Roosevelt, Frank Stockton, William Thackeray, and Mark Twain.

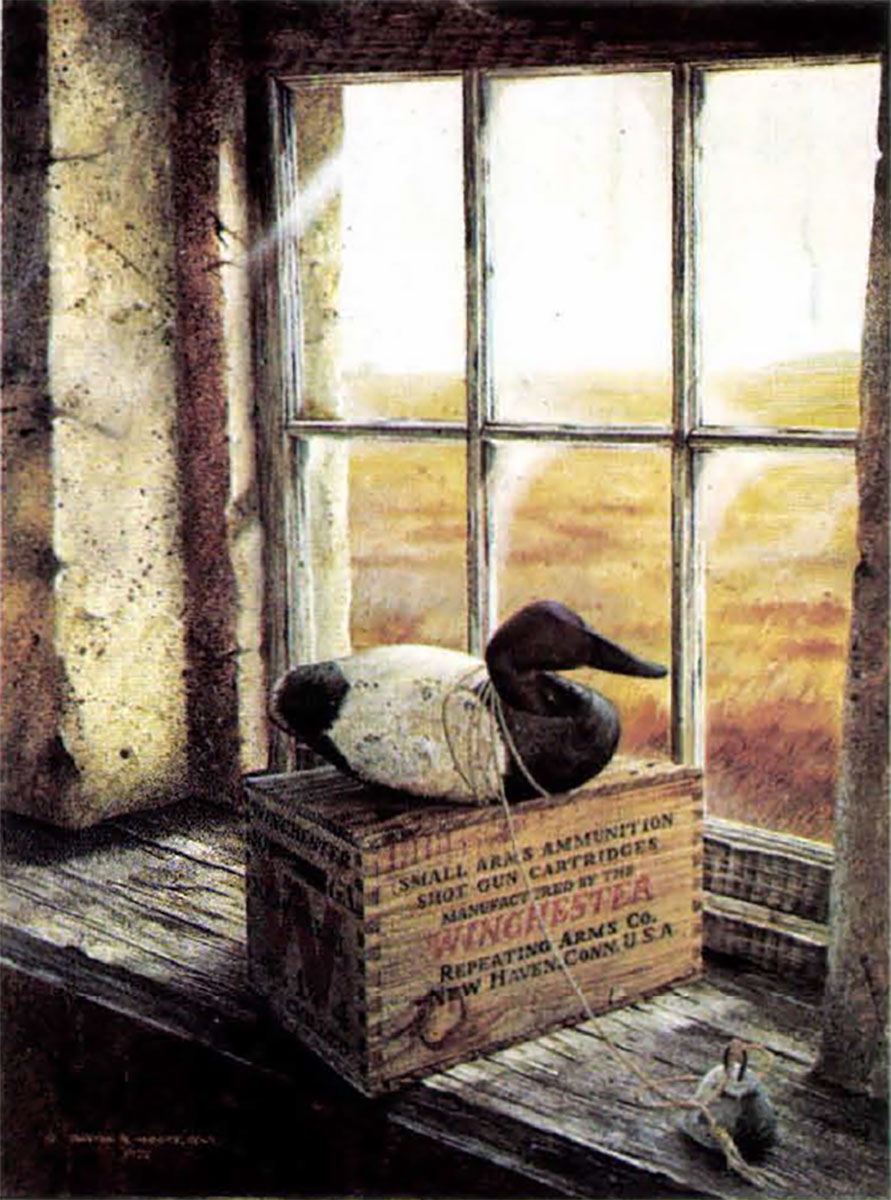

This print of A. Lassell Ripley s After Grouse was purchased for just $75.

It was A.B. Frost who breathed life into Harris’ Uncle Remus characters — Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Tar-Baby, Mr. Possum, and the others, but his definitive sporting scenes outshined everything else he did. “No one ever equaled his ability to depict the mood, the detail, the authenticity of sporting scenes,” wrote Eugene V. Connett in his foreword to The A.B. Frost Book. During the golden age of illustration, painting at his large country estate called Money sunk near Morristown, New Jersey, AB. Frost was the “Sportsman’s Artist.”

Following in Frost’s heroic footsteps, Lynn Bogue Hunt (1878-1960), born in upstate New York, was probably the most productive shooting artist during the first half of this century. A lifelong sportsman, Hunt painted brightly-colored canvases exploding with drama. From boyhood, his studio was the vast outdoors.

“There was never a keener gunner than this lad,” he said of himself as a youth, “and in addition to his enthusiasm for shooting he was endowed with … an ability to draw [the birds he bagged]. Since he could not bear to stuff the handsome creatures into the pockets of his shooting coat, he carried paper to wrap them in, one by one, that they might reach home unruffled and unsoiled, to become models for the artist.”

In an era before modern color photography, Lynn Bogue Hunt sold covers to almost every popular periodical in the country He painted more than a hundred covers for Field & Stream alone, and turned out advertising art for the Remington Arms Company. The 50-plus first-rate books he illustrated include Grouse Feathers and More Grouse Feathers for Derrydale Press.

Eight years younger than Hunt, William Harnden Foster (1886-1941) was both artist and writer. In the 20sand 30s, Foster edited National Sportsman and Hunting and Fishing magazines, doing most of the covers, and writing and illustrating articles, stories, and columns. His classic New England Grouse Shooting was published posthumously in 1942and again in 1970.

A grouse dog lover who kept pointers in the kennel behind his home in Andover, Massachusetts, Foster also served as secretary of the Association of New England Field Trials Clubs. Liked famed bird dog painter Edmund Osthaus before him, he painted portraits of national field trial champions for DuPont calendars.

A.B. Frost and Lynn Bogue Hunt were largely self-taught as artists, but Foster studied three years at the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston and another three years at the Howard Pyle Art Colony in Wilmington, Delaware. While working as a magazine editor, Foster helped invent the game of skeet.

By mid-century, A (Aiden) Lassell Ripley (1896-1969) and Ogden Pleissner (1905-1983) were the sporting painters of their day. Both were academically trained landscape artists and eminent watercolorists (although Pleissner also painted in oils). Ripley studied at the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston, Pleissner at the Art Students League in New York.

Ripley was already an established landscape artist and portrait painter when he began adding hunters and bird dogs to his landscapes about 1930. The success of his first exhibit of sporting paintings at the Guild of Boston Artists (to which he had been elected by a jury of his peers including Frank Benson, John Singer Sargent, and William Paxton) proved the turning point in his career.

During the Depression, when his paintings sold slowly, Ripley taught briefly at the Harvard School of Architecture (where one of his students was cartoonist Al Capp, whom he considered hopeless as a draftsman). Later, acclaimed for his ability to render color, atmosphere and light, Ripley had his pick of commissions. In the name of research, the artist enjoyed great gunning and choice fishing at some of the best locations in the country.

Brooklyn-born Pleissner considered himself “a painter of landscapes who also likes to hunt and fish.” During a career that spanned 55years, he painted 2,500 large oils and watercolors, twice that many small paintings, and oversaw the production of signed limited edition prints from more than 30 of his paintings.

Fall Woodcock Shooting shows a theme that appears in many A.B. Frost works: A lone hunter moving in behind his dog for the flush.

Prior to World War II, Pleissner spent his summers in Dubois, Wyoming, where he fished and painted western landscapes. Beginning in 1943, he covered the war in Europe for Life magazine, producing more than 80 paintings in England, France, Belgium, Germany, and Italy. Thereafter, into the 1970s, Pleissner and his wife Mary returned to Europe each year to paint and fish and hunt in Scotland and England.

Pleissner had no time for run-of-the-mill sporting art, believing that it lacked feeling. A good painting is more than subject, he pointed out, it hinges on the feeling conveyed by “form, bulk, space, dimensionality, and sensitivity.” The word Pleissner used for it was mood.

Continuing the tradition of fine up land shooting art in America today are Robert K. Abbett, Chet Reneson, and Eldridge Hardie. Like their predecessors, all of them thrill to the hunt, and their art reflects the lives they lead.

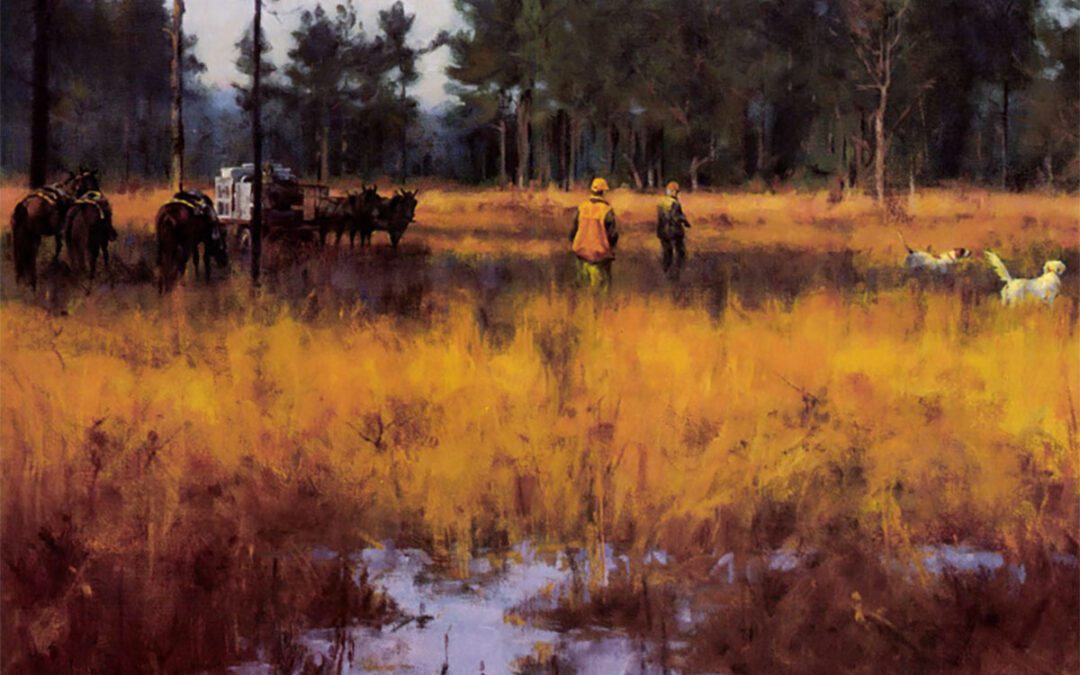

Robert K. (Bob) Abbett, a commercial artist on the fast track in Chicago and New York for 20 years, changed gears when he moved tohis present farm in Connecticut in 1970. With property enough “to walk out of sight on,” he has explored “once again the excitement of on-site landscape painting.” Nature has come into sharper focus in both his life and his oil paintings.

A genius at what he does, Bob has set new standards for shooting art and gun dog paintings. Not satisfied to let go of a good day’s hunting with a friend and a dog, he paints a picture of it. Inspiration is seldom a problem for Abbett who “turns on quickly to the beauty of nature in all its shapes and textures.”

As an easel painter, Abbett counts the freedom to express himself in his work as his most valuable asset. This honesty is what makes his paintings work. “When present, it is the very delicate filament which lights the paintings from within and makes it special.”

Chet Reneson lasted six years as a commercial illustrator in New York before striking out on his own to paint sporting scenes in 1978. Like Ripley and Pleissner, Reneson is a master draftsman who expresses himself best in watercolors.

Taking his cues from artists like Winslow Homer, N.C. Wyeth, and the French Impressionists, Reneson has developed an easily recognizable style of his own that is strong on design and uncluttered. His vibrant paintings of hunters and dogs on warm fall days in the uplands need no signature.

Eldridge Hardie graduated first in his class from the Washington University School of Fine Arts in St. Louis in 1964. His distinctive style can be traced to the influences of the Old Masters — Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Cezanne, and Velasquez. In 1966, Hardie moved to Denver for reasons that included good bird hunting and fly fishing.

A versatile artist who works in oils, watercolors, and pencil, Hardie characterizes his painting style as “representational but not tight or slick.” A stickler for accuracy, which is not to be confused with feather painting, he focuses on creating a total atmosphere — the weather, light, weeds, trees. His own hunting and fishing experiences are the “grist and soul of my art.”

In the end, the best sporting artists are skilled translators of ideas. The art of upland hunting will continue to evolve with the times, but it will always rely on firsthand gunning experience, for which there is no reliable substitute. Bob Abbett sums it up nicely when he says:

“Being there is honesty for an artist.”

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1991 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

Featuring more than 200 decoys and hundreds of historical photos, maps and documents Lloyd Newberry traces the fascinating story of the Cobb Family through three generations. It’s a chronicle that historians and folk-art collectors will find both educational and enjoyable. Buy Now

Featuring more than 200 decoys and hundreds of historical photos, maps and documents Lloyd Newberry traces the fascinating story of the Cobb Family through three generations. It’s a chronicle that historians and folk-art collectors will find both educational and enjoyable. Buy Now