He was all alone now, but the birds were still there.

He was called Mars because new names can become scarce around a big kennel and someone had come up with Jupiter and with Mercury (shortened to “Mere” and “Jupe” for other pups). Later, he was registered as Morton’s Own Mars.

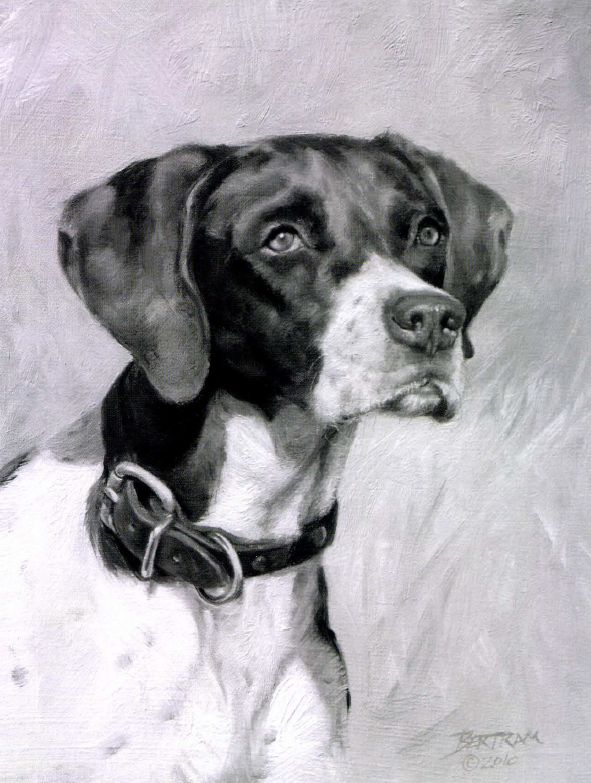

He was black and white – black around his head and ears with only one black spot on his light flank. They called him a Rip Rap, an honored black-and-white name from a century before. They showed him a quail’s wing on a pole, but he wanted to catch it instead of pointing at it first and seemed to think very hard about that. He scented a trace of something important, but it appeared he wasn’t sure what it meant.

John Morton, grinning a little ruefully, bought him when he was still a puppy. Morton was no longer young but he was lean with a sort of reach to his walk. Mars followed years of other bird dogs, the silky setters, the worshipful Brittanys, other leggy pointers and a German shorthair that had known about pheasants. At times there had been several dogs at once.

Morton said, “I guess I’ll finish up with you, buddy,” and Mars was a little confused – old enough to know his life was being changed.

The Mortons were a little past the edge of town – not a very big Florida town – and nearby were sand roads that went through old orange groves and past shaded ferneries. There were quail calls – not just bobwhite but other quail talk seldom recognized, and young Mars pointed a stray covey between the backyard and the stand of pines.

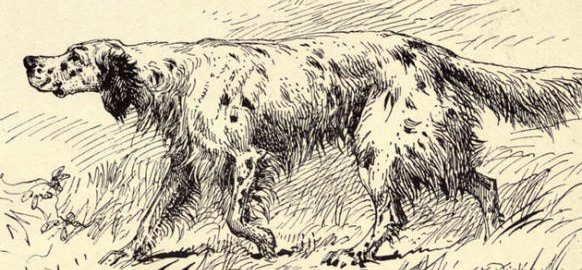

It was the ancient blood of Spanish ancestors, and later ones of England and France that made Mars motionless when he caught the scent, incredibly strong and cut sharply from a thousand other smells. He pointed and quivered as a hundred generations of pointers had done, but we do not know what he felt, only that he was doing what he had been born to do and that nothing else was so important.

“Pointing dogs are bird machines,” Morton had said, “not pets or house dogs, but bird machines.”

But Morton did not quite believe it. There were small tombstones near the piney woods, carrying typical dog names, and when Morton walked that way he walked slowly.

For more than ten years there were quail, often in familiar places that Mars learned to know by the special covers and special smells. Mars ran big in the wide country where the Dakotas’ oceans of grass seemed endless and the sharptail grouse were hard to hold in the draws with streaks of brush in the bottoms. They were different from the quail of the old orange groves and the scrub oaks, but there was the magic gamebird scent that called on the blood of hundreds of years of ancestors, some of them champions. We do not understand it, but we know it was there.

In Michigan, the fall aspen were gaudy and the ruffed grouse roared from bushy patches or sometimes sailed silent as owls from higher perches. Woodcock, strangest scent of all, moved with their ghostly wing whispers and tried to disappear through walls of leaves.

In Canada, there were the Hungarian partridge, feeding in immense grainfields or resting about silent and abandoned homesteads, monuments to long ago and faded dreams. In the Southwest there were the running desert quails and dog boots to protect from the desert things that jab and prick.

But at home there remained the nearby coveys of quail, and when the grouse woods were banked with snow, Mars and his master looked nearby for quail that had been there for countless generations – the sinkhole covey, the old oak covey and the camphor tree covey – especially the camphor tree covey.

The camphor trees were not native, of course, but had come there with the builders of an old shed, now shabby and crumbling. There had been a house too, but only the foundation outline remained. The camphor trees were in a row and on one side of them were the pines. There was a patch of broomsedge on the other side, and some partridge pea, and there was some brushy, thorny cover along the row of camphors.

The camphor tree covey must have been there long before Morton had found them, but he had followed several generations of dogs there, a short way from home and perfect for an hour or two with a single dog. He was careful not to over-shoot the birds and in especially good seasons there would be two or more coveys nearby.

Through the years, Mars knew the place as only a hard-hunting dog could learn it. No one accompanied him and Morton when they came to the camphors. It was a private place. Mars was more than ten years old, but he didn’t know that. He ran a bit more slowly, but he knew where the birds should be. There was a scar across one foreleg where something had cut him on a mountainside, and he had heard the soft cackle of chukar partridge on that day.

There were many little scars on his black ears from thorns and other things, for when he was younger he had done 100 miles of hunting a day; and there were gray hairs about his muzzle and eyes, showing plainly where there had once been glossy black. His ribs showed a little as they always had when he was in good condition. He was really not a very pretty dog and neither very big as pointers go, nor very small, and he weighed a little less than 50 pounds. Mrs. Morton had said he really wasn’t much trouble.

There were many little scars on his black ears from thorns and other things, for when he was younger he had done 100 miles of hunting a day; and there were gray hairs about his muzzle and eyes, showing plainly where there had once been glossy black. His ribs showed a little as they always had when he was in good condition. He was really not a very pretty dog and neither very big as pointers go, nor very small, and he weighed a little less than 50 pounds. Mrs. Morton had said he really wasn’t much trouble.

“You don’t know about this,” Morton told him, gently scratching an ear as he had done all those years, “but you and I are about the same age as men and dogs go. There’s a time to slope off a little, the way we’re doing now – and I guess there’ll be a time to quit.”

After that, Morton took his shotgun from the old log and they hunted some more. In his youth he had used many guns, but now it was only this one – a very good double gun from England, but a very plain one with the blueing worn from much of the barrels, leaving them dull silver, and the good walnut showing honorable scratches from a dozen states. There must have been some scratches from the camphor tree cover.

It was early fall that year when Morton came out to the kennel several times and let Mars circle the yard, pretending to point the doves by the rosebushes and play-pointing the gray squirrel that made squeaky barking noises from the golden rain tree. Morton did not wear the high leather snake boots or his heavy canvas pants and he never wore his whistle – but there was something wrong with the whistle anyway for Mars had not heard it very well lately.

And then there was a time when others brought Mars his food and scratched his ears. Sometimes it was one of the grandchildren and once or twice it was total strangers. They told him he was a good dog.

And then there were a number of people at the house and even the grandchildren wore their goods clothes and things were very quiet. After two days most of the visitors left and it seemed very still, and Mars stood in the center of his pen with his tail down and he probably thought very hard, but we do not know that for certain. He walked to a corner of his pen to the place where he knew he could crawl under the fence but never had, and this time he went under, flat on his lean side and working with all four legs. Then he shook himself and trotted away, past the stand of pines back of the yard and past the little tombstones and on to the sand road. He did not search the roadside weeds but followed one of the dusty tracks steadily.

Mars followed the sand road and turned from it on two sand tracks made by occasional cars and trucks, and he went past the frozen-out orange grove where he’d pointed quail the year before and where Morton had laughed when Mars tried to daintily retrieve two birds at once. The dead Australian pines in the grove were tall and ghostly and made the place look like an old battlefield. There were doves feeding by the road there, but Mars showed no sign he had seen them when they flew. He paid no attention to the gopher tortoise that paddled across the sand tracks.

It was another half-mile to the camphor trees and when he neared them he put up his head and his tail whipped a little, much as it had years ago when he first found the camphor tree bunch. He caught the breeze and turned a little upwind with his head up, and twice he lowered it for some trace of smell that hung close to the ground.

It was only a few minutes when he caught the gamebird scent, treasured through the centuries by his ancestors, and he moved soft-footed for the birds were some distance away. His belly went closer to the ground and his muzzle reached toward the birds, reporting to him in some mysterious way that they were moving, and he made a stealthy little half-circle to stop them cold, and then he had them without doubt and his stance changed from fluid to erect and solid, unmoving.

He stood there for some time, head and tail erect, and the quail held for him but there was no steadying voice from behind him and no sound of boots moving in the weeds. A blue jay watched him from one of the camphors and made no sound at all. There was not the slightest rustle from the quail. There were 11 of them but Mars could not know that.

Finally, Mars lowered his tail a little, and he backed away carefully, so gently that the quail did not move, and the blue jay only tilted its head a little. Mars turned away and went back to the sand road and left, his head low and his tail down. He trotted slowly on the warm sand and he went just a little sidewise as dogs have always gone.