In Marc Hanson’s personal hierarchy it will always be fine painting, not subject matter, that takes precedence.

There’s a painting in Marc Hanson’s studio that fans of his art will probably never see. It’s a simple piece, really — a winter landscape that is likely Minnesota, but could be anywhere. Snow-covered trees bend gracefully under a considerable mantle, the sky is grey and ashen. From the lower left corner of the canvas a ski trail emerges; two parallel cross-country tracks that bring your eye to focus at the painting’s center, then snake off through the winter scene and disappear.

The Artist

There are no birds gracing pine boughs, no subtly hidden critters and, most conspicuous by its absence, no skier. Yet the ski trail appears smoking-fresh and the viewer is left to wonder: Who is the path maker? Where’d he come from? And, more importantly, where’s he headed?

I’d spent the better part of an afternoon in Hanson’s studio and commented on the ski trail piece a couple of times before the soft-spoken artist admitted it was one of his favorites. I nodded vigorously in acknowledgment (we profile writers are ever-vigilant for those self-revelations by our subjects), scribbled the comment on my pad, and somewhat coincidentally, noticed a handwritten sign on the wall across from me. Neatly lettered, the motto read simply, “Savor the Path As Much as the Destination.” My gaze switches back to the painting, then over to Hanson, whose own stare is following the parallel Tracks as they disappear into the wintry scene. The juxtaposition of artist painting-motto is too perfect to b coincidence, and I realize I’ve just had an important look at what Marc Hanson is all about.

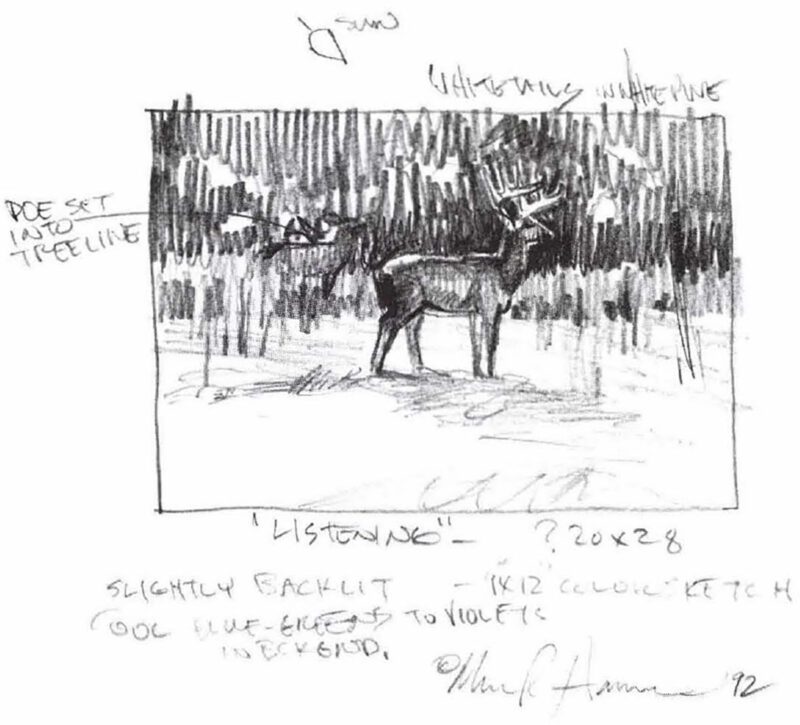

Hansons conceptual sketch for Listening provides insight into the evolution of a painting.

Marc Hanson is indeed one who enjoys the traveling as much as the getting there. This is most evident when you try to get Marc to talk about his successes. There have, after all, been many: he was among a handful of top artists commissioned by the National Geographic Society to illustrate a field guide to North American birds; he has been included in five Leigh Yawkey Woodson exhibitions and several world tours; he was named Artist of the Year by the Minnesota Conservation Federation, and he makes a good living in the increasingly competitive world of wildlife art.

But Marc Hanson will never give you the impression that he has arrived. He will talk at length about the path he’s been on; who and what has influenced him, for example, and where he’s going; he sees a broadening look at painting wildlife, especially big game, in his future. But trying to get Hanson to wallow, even splash around a little, in his success is a futile goal. He will only stress, gently but emphatically. “I am not anywhere close to where I want to go.”

Perhaps this refusal to settle into a groove and get comfortable is a reflection of his childhood. The son of a career Air Force navigator, Hanson’s youth was one long move. “I went to three different high schools and many grade schools,” he recalls. “I was in Alaska for a couple of years as a baby, then we lived in northern and southern California, moved to Nebraska, Arkansas, Norway, South Dakota and back to California. I was told later how awful that must have been, always being the new kid, but I thought it was great at the time.”

Listening

Hanson had artistic influences early; his aviator father was “a cartoonist/wannabe artist. I was always the kid who illustrated the school newspaper, but I never really took classes or anything.” Hanson was, however, deeply interested in something that would affect his future in a big way: birds. A love of ornithology was also a gift from his father, who had majored in waterfowl biology before settling into his aviation career.

Much of Hanson’s success as an artist can be traced to his sensitive portrayals of birds. “They have been interesting to me as long as I can remember, and flight had a lot to do with it,” Hanson says. “When I was young, we built countless gliders and radio-controlled airplanes. I collected a lot of butterflies, too, and hunted birds with a cork gun. And of course, I went flying with my father.”

The elder Hanson earned his wings early. Marc notes that when his father approached driving age he begged his parents for a motorcycle. “They were convinced that motorcycles were too dangerous and that he’d hurt himself. So they bought him an airplane instead.”

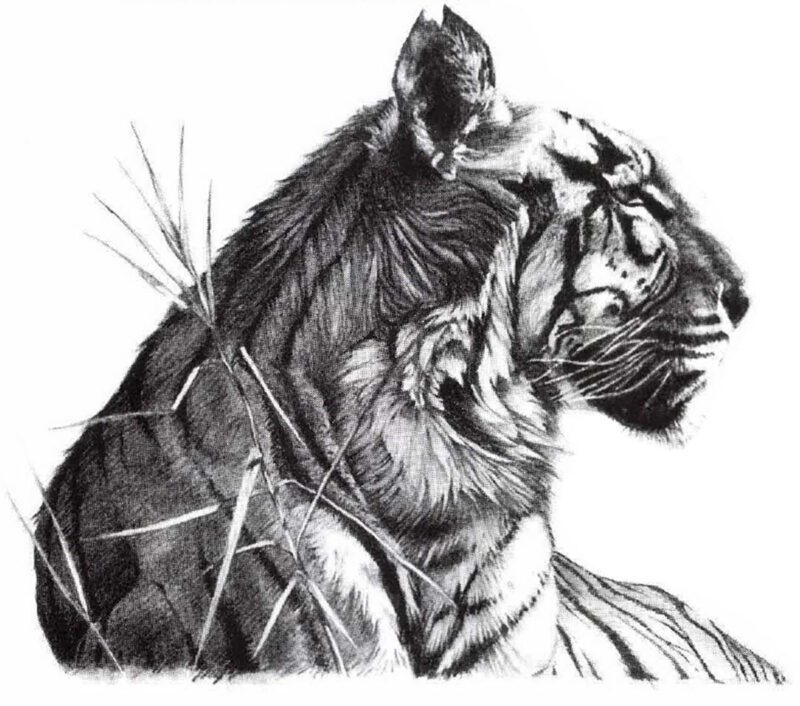

His great horned owl in Master of the Valley first took form as this pencil drawing of a captive bird.

Marc’s interest in flight remained with birds, though, and after graduating from high school he found himself at a crossroads. “I didn’t know if I wanted to study ornithology or teach skiing (an expert downhiller, Hanson had been an instructor since a teen), so I decided to go to art school,” he quips. Marc did study biology for three years at Rocklin, California’s Sierra College, then applied to the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. The school is famous for turning out many of the Disney animators, as well as some top designers and illustrators. He studied at the Art Center for two and a half years, learning the technique and style he would later carry into his career. “I can’t say that formal art training is necessary – there are a lot of artists in this field who don’t have it — but it can save you a lot of time. You learn techniques that would take years to pick up on your own.”

By the time his Art Center stint was up, Hanson knew that he wanted to paint wildlife full time. The California wildlife art scene, however, was not a particularly encouraging one. “Back then, there was only one wildlife art gallery in Northern California. But I had a grandmother in Wabasha, Minnesota, so I knew all about Wild Wings. I just packed up everything in my Vega and moved out there.”

The artist did not, as one might suspect, find immediate success. True to the starving-artist scenario, Hanson had to do his share of part-time work before anything resembling a “break” would come along. Fortunately, one of those side-jobs seemed tailor-made for a young, adventurous outdoorsman with an artist’s eye.

“I got a job tending bar for this beer-drinking, cigar-smoking river rat named Slippery,” Hanson laughs, remembering legendary Mississippi River man Richard “Slippery” Bach, who died in April, 1992. “I wouldn’t want to guess at his life story. We’d work at the bar until two a.m., clean the floors until four, then go out duck hunting. Slippery would usually put me on some great spot named ‘Mallard Point’ or something. Then he’d go back in the woods aways so I could have some shooting. After I’d take a couple of mallards, I’d just sit there and watch the birds come in to the decoys — and Slippery would be back there, swearing away at me.”

Master of the Valley

Despite his apparent rough edges, Bach was “a person who loved both the arts and the outdoors. “He knew every cut, slough and wing-dam in the Mississippi River bottom lands, where a newcomer could get lost for days.” With Bach’s encouragement, the young artist began displaying his paintings in and around Wabasha, eventually drawing the attention of Wild Wing’s founder Bill Webster. The sporting opportunities offered by Slippery, and the chance to market his work with Wild Wings (Hanson also sells his art through Jack Dennis’ Wyoming Gallery), were enough to finally anchor him in one area; he’s lived in southeastern Minnesota since his fateful move east.

There were, however, other attractions. Shortly after his migration to Minnesota, Hanson met his wife Anne (whose family, by the way, runs the locally famous Nelson Cheese Factory. Stop in after a day of chasing ducks or fish on the river and you can sample some of the best cheese and/or ice cream that Dairyland can offer); the two raise sons Fred, 9, and Erik, 7, in nearby Rochester.

Marc Hanson has settled into an idyllic lifestyle. He’s happy in Rochester and has jumped into fatherhood, enjoying his involvement in Cubs Scouts and baseball. And while he admits that his career is doing well, there will always be, I suspect, an underlying restlessness in him. At least when it comes to wildlife art.

“I think there are certain artists who were born with a lot of talent,” Hanson says. “I think it’s probably just a greater hand-eye coordination than most of us have. Others have to work very hard to achieve that success, and I feel I’m one of those people. I’m pretty much a 9-t0-5 painter, and I could go much longer if my family weren’t so important to me. I know I could work 15 or 16 hours a day if I had nothing else to do.

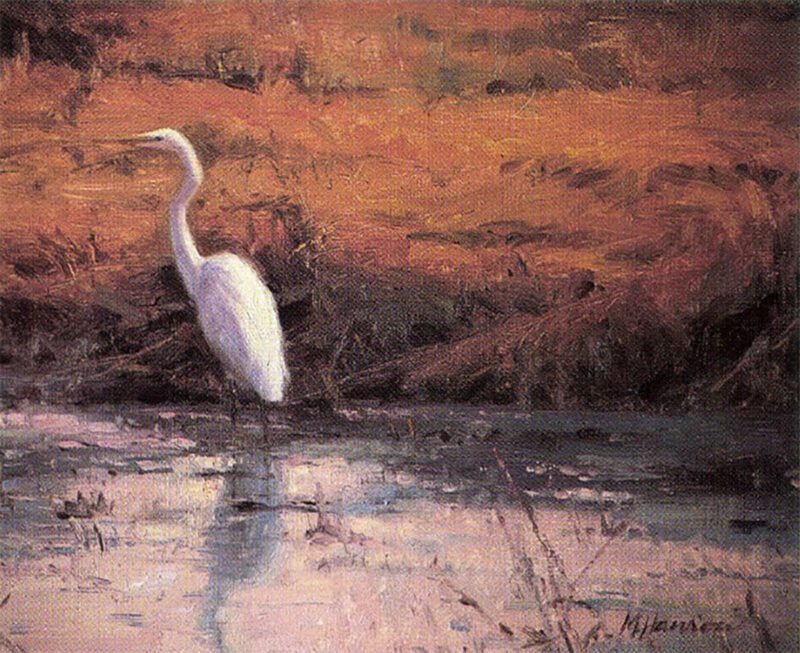

Early Spring Egret was a study for a larger oil.

“If I could combine the qualities of three artists into my own work, I would take the technical eye and ability of Richard Schmid, the flair and painterly qualities of Joaquin Sarolla and the anatomical abilities of Bob Kuhn. Put those three together and I think you’d have someone who’s pretty much unstoppable as more than just a wildlife artist.”

Hanson’s constant quest for improvement, and willingness to receive advice and instruction, opens him to the influence of other artists. He’ll enroll in a fall workshop under Chinese painter Zhang Wen Xin, and his study under Richard Schmid was an important influence. “Schmid helped me to see there’s more to wildlife art than just depicting the animal’s coat. He calls painting ‘the language of seeing’ and showed me a lot about being honest when you paint. Schmid was also the one who got me painting and sketching outside.”

Working “plein-air” is a big part of Hanson’s work and, he feels, an important contributor to his growth as an artist. “I do a lot of that now – I really think it allows you to pick up some of the subtlety in nature that you’d miss otherwise. Of course, it can be more of a challenge when the weather turns cold,” he laughs.

Observing wildlife is a favorite part of Hanson’s hours in the outdoors, but the perks don’t end there. “I get a lot of joy out of the sounds and smells in nature. In fact, when I’m painting, I think about these things as much as I do the subject.”

Hanson demonstrates his versatility in this detailed drawing of a tiger.

Listen to Hanson describe his process, from germinating idea to finished canvas, and you’ll hear an artist who’s infatuated with every aspect of his work. And, though he’ll admit not every painting flows easily, Marc recalls a recent piece where everything truly gelled. “I’d decided to do a loon painting, so I went to a northern Minnesota state park the third week of September. I had the place all to myself. I rented a canoe, threw in my camera and sketch pads, and paddled out on this lake. I soon had loons dancing around me on the water. I shot all the film I had, put down my camera and did some oil sketches. When I left the loons, I went to a stand of virgin white pine and started sketching those when some deer showed up. On my way back to the vehicle I walked past an alder bush and noticed five grouse eating buds, so I sketched them, too. I packed everything up and came home, all inspired. I finished Autumn Shoreline — Loons in five days.”

While the completion time for Hanson’s popular loon painting was atypical, the subject matter was not; he’s built his career on images of birds. Songbirds are major Hanson subjects, and game birds, especially pheasants, make strong appearances. But don’t make the mistake of thinking a creature has to sport feathers to appear on his canvas. This fall, for example, he’ll be chasing area whitetails with a bow and plans to incorporate them, and other big game animals, into his work more frequently.

“This bowhunting experience will really be nice for me. I want to do more work with whitetails and other large animals. That will give me a lot more latitude when working with landscape and background, which I love to do, than you have with songbirds. Songbirds especially are so small that it’s always been a personal challenge for me to meld the correct biological aspects of the bird and the painterly aspects of the background without one taking over. Big game will allow me to push my paintings toward a larger, more direct style.”

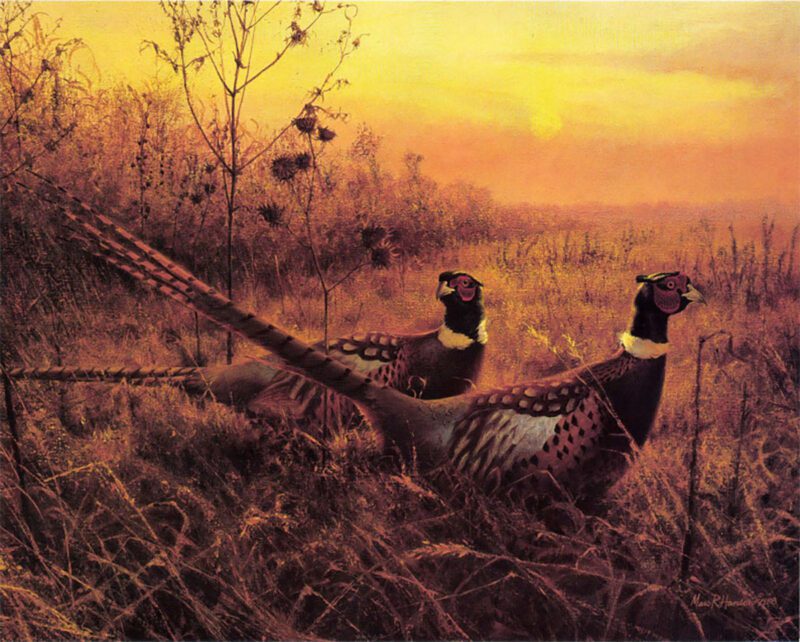

First Alert – Pheasants, a popular print for his publisher, Wild Wings, Inc.

If personal experience is the vehicle or Hanson’s art, fans might also look for more pheasant paintings, and maybe a fly-fishing scene or two. Marc admits that he’s not “one of these camouflaged hunters who’s out there 50times a year,” he sees a lot of pheasant hunting in his future. He’s in the process of getting his sons, and an English cocker spaniel, attuned to the sport. Area trout streams, among the best in the Upper Midwest, are a magnet for the talented painter/sportsman, and he’s fallen victim to the charms of taunting trout with flies he’s tied himself.

But in Marc Hanson’s personal hierarchy it will always be fine painting, not subject matter, that takes precedence. Minuscule nuthatch or statuesque elk, staring owl or strutting turkey, all will share the sensitivity to color and mood that characterize a Hanson painting. While the introspective artist admits to “a lifelong goal to have the anatomical knowledge of Bob Kuhn; it’s also clear that he is concerned with far more than careful rendering. Instead, Hanson advises, look at his paintings for “painterly things … color and brush strokes.” I’ll add one of my own: the eye of an artist determined to bring his unique vision of the animals he sees to life on canvas. “Being a painter is pounds of paint and miles of canvas,” Hanson will tell me before I leave. “But it also takes a subtlety of eye that takes life experience to develop. A building of experiences allows you to ‘see’ that way.

“I’m not normally one to notice stuff like this, but Marc Hanson was standing within a couple of feet of the ski trail painting when he made that remark. I can’t guess at the directions that bright young artist will head, but I’m sure he will, as the nearby, neatly-lettered sign said, “Savor the path…”

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now