An infuriated, full-grown bull moose, with eyeballs of most spiteful fury and making mighty lunges straight for you, is absolutely terrifying.

It was in the forests of lower Canada, in front of a glowing campfire after a day of fascinating sport with the Salmo fontinalis, or spotted brook trout, with our tent duly pitched under the cedars on the shore of the lovely, yet sometimes bold and rapid Madawaska River that the story was related.

Dr. Stephen Griggs of Brooklyn and myself were taking a canoe trip on these waters from their source in Mud Lake to where they flowed into the St. John at Edmundston in the northeastern corner of Maine. Peter Theriot of Caribou was our guide.

Scarcely out of his teens, Pete is a physically powerful young man who is skilled in woodcraft. From his trapping experience, he knew the entire region of the Tobique—the Green, the Restigouche and other rivers, and had killed much game, large and small.

Pete was returning one day from his customary visit to his line of traps—which run for 20 miles or more—that he had set for mink, fox and other creatures according to the country and conditions. He carried a medium-sized, single-barrel, muzzle-loading gun, charged with buckshot, simply to be on the safe side.

It was in the afternoon, near the end of his circuitous route. The heavy load of skins on his back attested not only to his skill, but to the fact that his physical powers that day would be drawn upon more than usual.

Timber by Carl Rungius

Walking rapidly over a little rise of ground, he suddenly came upon an immense bull moose lying in the forest. The range was very short, so Peter quickly raised his gun and fired at the moose, the heavy buckshot rattling against his antlers. Stunned and wounded, the massive animal dropped to the ground.

Pete’s joy knew no bounds when this unexpected forest inhabitant, for which no trap had been set, seemed likely to be an additional trophy to the spoils of the day. Drawing his hunting knife, he sprang forward, unfortunately leaving his gun behind, to cut the animal’s throat, after which the blood would run freely and the meat would be in better condition for the morrow when, with help, he would return.

Approaching quickly but with great precaution, Pete had just started to slice the animal’s throat, when presto! Like a dash of cold water, the prick of the cold steel apparently revived the moose, which jerked back his head and, in a moment, as if its 1,200-pound form had suddenly been filled with powerful springs of steel, regained his feet.

Pete jumped backward and stood face to face with the giant, which issued a long snort, evidently betokening war. Doubtless goaded by pain, the moose aggressively lowered its massive antlers and charged the young guide.

Reader, have you ever seen a full-grown bull moose? The bulls of Bashan, the warhorses of the Orient, the excited Amazons of fable—none can surpass his really formidable look. But let him be infuriated, his bristly hair standing up along that immense spine, his most ungainly snout below, those mammoth horns above, those eyeballs of most spiteful fury and making mighty lunges straight for you—these things altogether can be absolutely terrifying.

The moose was so close that Pete could feel the hot, panting breath from his furnace-lungs. Pete dexterously leaped to one side to avoid the animal’s plunging body. That would be his most narrow escape, and only the greatest agility and strength on Pete’s part enabled him to avert disaster and death.

In a twinkling, Pete cut the straps holding his bundle of spoils as he started to the nearest tree, with the moose close behind him. Happily for Pete, the bundle of skins tumbling down behind him caught the moose’s attention, leading him to think, if a moose ever thought, that here was a portion of his enemy’s person, and thus giving Pete the second of time he needed to get behind a tree.

One plunge of the moose’s antlers scattered the skins and showed them not the hide he was after. Apparently, he became even madder for being fooled, and rushed toward the tree, behind which, with hunting knife still in hand, Pete stood, every muscle tense, awaiting the fearful charge.

On the moose came, plowing through the snow and making the frozen earth fairly rumble with his cantering hooves. But the moose had to take the one side or the other because the tree, fortunately for our guide, was too large to be broken down. Of course, the side that the moose took would be minus Peter and, as the moose could not fight backward, it had to turn around each time to renew the fray, giving Pete a breath and a half for recovery.

After some half-dozen terrific lunges on the part of the moose, leaving hair from his scraped side on the back of the tree, Pete thought he had a chance, unless he should stumble, but as a half-hour of this unique man-and-beast contest had left the moose apparently as fresh as ever, Pete began to worry about his endurance. He had already done a good day’s work with his traps, and was not physically fresh for this unexpected foray. He also needed food, and began to think and to reason.

The moose seemed to realize he was making no headway and would stand for some time, apparently studying the situation, then would start his deadly game again.

Up to this moment, Pete had had no chance to look around. His eyes had to narrowly observe and his alert muscles had to quickly follow, the directions that the brain flashed to them.

He began now to study his situation and to look around him. A little way off was another tree, and from its stock near the ground grew some wrist-sized shoots. A thought struck him—a tactful thought—a possible father of a possible deed, and he at once proceeded to put it into execution for Pete knew that the setting sun could bring no darkness that would enable him to escape. He also well knew the bulldog tenacity of a moose, for once before he had been treed and kept up in it until, after a day’s sojourn in that peculiar bivouac, his companions had secured his release.

Watching his chance, when the moose dashed by him in the opposite direction, he sprinted off to the other tree. The moose rushed forward with increased speed, but came up and found the same old objection to a free fight: an intervening tree.

Holding his hunting knife in his teeth, Pete now took off his loose-fitting but warm hunting jacket and threw it to one side. He was having exercise enough to keep warm, so he took it off for fear that one of the prongs of his enemy’s antlers might catch in it, and so be the means of giving the moose the victory.

The moose made a dash for the garment, but like the bundle of skins, it afforded him no satisfaction. With his hunting knife, which was stout and strong and double-edged, Pete proceeded to trim off the superfluous twigs and upper growth of a sprout. He left it about as long as a broom handle, then he commenced to cut it off at the base. All of this had to be done while on that side of the tree, because the moose kept him moving most of the time. It was slow work, but finally, after several vigorous thrusts with his staunch and trusty blade, he succeeded in wrenching clear and free from its parent stock that strong, young shoot. His eyes gleamed with hope as he handled it, hefted it and measured its capabilities.

After such further trimming to smooth its surface as his continual forest dance would allow—for the moose got madder yet, apparently, when even a short respite came—Pete cut a few small creases like the thread of a screw around the smaller end and shaved one side of it flat for nearly six inches. He laid the handle of his hunting knife upon this flattened surface, and looked carefully for any place where a little removal of wood would make the handle fit as snug as possible.

Then, after a little more paring, under circumstances that naturally would take pieces of fingers with it, a bigger hope shone in his eye. Neither he nor the moose had yet uttered a sound.

Now Pete took from his breeches pocket the always-carried buckskin string and, laying the handle of his knife upon the end of his impromptu spear handle, with its double edge of steel for the projecting blade, he commenced to carefully and strongly tie the thong into the notches made for its firm holding. He took up all loose places, and made that hunting knife and handle feel, and practically be, like one solid piece.

Then, very coolly taking from his pocket a small piece of Nova Scotia whetstone about the size and shape of a package of chewing gum, he turned the spear point up, as a woodsman does an axe and, after moistening the stone with saliva, he plied it in a lively manner with, apparently, as much nonchalance as a barber does a razor to his favorite hone.

Many times he had been obliged to change his position, but his physical strength had up to this time met every demand upon it. He knew the fight had but just commenced; it was his turn now and, before the moose could take the least precaution or realize the changed state of affairs, he thrust the keen blade around the tree like a flash into the bottom of the moose’s jaw, inflicting a smarting wound. He followed it up with another stab right on the snout, as that was most exposed, and scored again.

In all these thrusts, he was compelled to exercise great care lest some prong of the quickly moving antlers should disarm him. As the moose came up against the tree, Pete put in his best work, reaching for the vital throat artery, whose location he so well knew.

What a fool the moose was! His madness took away his judgment. If he had just stood back a little way from the tree, he would have been out of Pete’s reach, but his very madness stood in the way of his own safety.

Pete’s skillful thrusts were beginning to tell, till finally, the great artery of the neck, to the joy of our guide, was severed, and a tide of blood now deluged the ground. The moose seemed to realize that his time had come. He stood with all fours well out from his body, and let the life-blood flow, as he must. It was the speediest, yet gentlest dissolution of great living forces.

Pete stood unmoved. The shadows of natural darkness and physical death were settling down together. The sun had gone down, and Pete knew the contest was over. While gratitude was beginning to swell Pete’s heart, the great monarch of the forest suddenly collapsed and fell to the earth.

Gathering up his hunting coat and scattered pelts, Pete returned to camp, leaving his last conquest for additional help on the morrow.

Note: This story originally appeared in the November 1902 issue of Outing magazine.

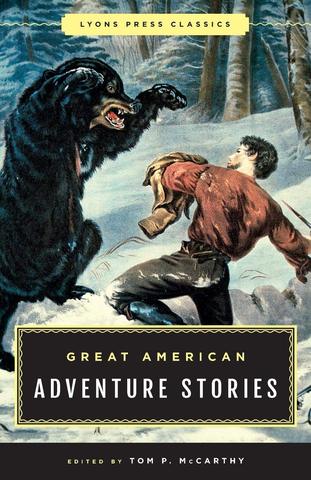

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today. Shop Now

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today. Shop Now