A few years ago, I stepped out of the Dennis Chavez Federal Building in downtown Albuquerque where I work. Outside in the cold wind around the corner from my office, ironworkers were hard at work. Passing by I turned up my coat collar and heard one man holler orders to a crane operator. A labored clomp of mallet on metal filled the air. Like a sculptor shapes clay, these guys turned a tangle of iron and concrete into a downtown building.

An ironworker 10 years my junior worked near the street. He heaved heavy rebar onto his shoulder. His tool belt hung low on his waist from the weight of a spud wrench, his clothes flecked with welding burns. His hard hat sported the Union Ironworkers emblem. My heart swelled.

My dad made ironwork his career. Ernie Springer walked the I-beams of bridges and tall buildings in the making. As a youngster I couldn’t fully know how hard he worked, but I appreciate my dad now more than ever.

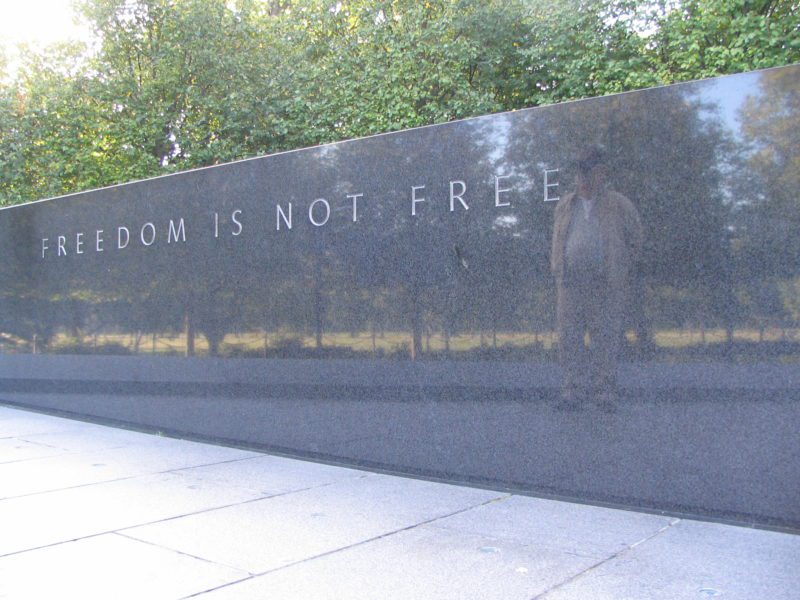

Ernie Springer reflecting on, and in, part of the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

In summer he’d come home from work covered in dirt and no doubt tired. Still, he somehow had the energy to take me fishing on many evenings. I recall summer nights with the shadows getting longer while we hoped for one more sunfish. When I got big enough he introduced me to quail and pheasant and was right there with me when I took my first game as a teen. Dad made it a point that I know the outdoors life.

When Veterans Day comes around he is heavy in my heart. He died the day before Veterans Day in 2009, leaving me with many memories and a dearth of answers to questions I never got to ask. Some of those questions arose after his passing.

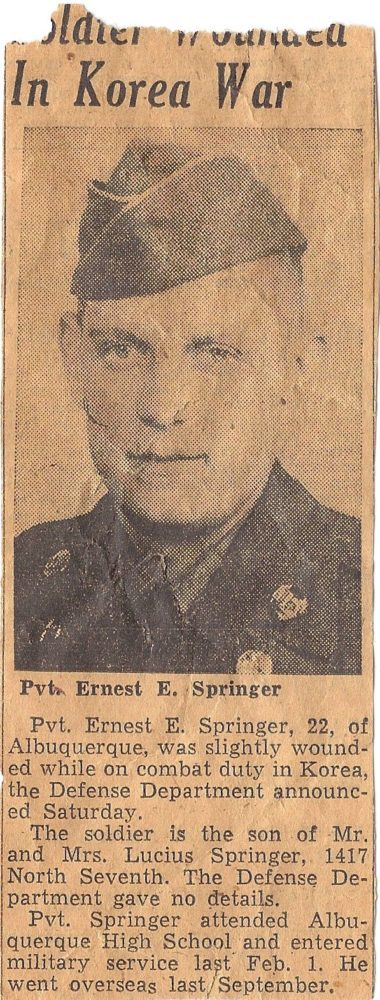

Through 1951 and part of 1952, Dad was on the front lines in the Korean War, a member of the U.S. Army’s famous 2nd Infantry Division. His unit was well inside North Korea. It was a meat-grinder experience, vicious and unspeakably violent, heightened by brutally cold weather. His time in North Korea was something he simply wouldn’t discuss at length.

But he couldn’t hide his limp. Each time he bought a new pair of shoes or work boots, the sole had to be stacked on his right foot to compensate for what happened in October, 1951. Enemy shrapnel earned him a Purple Heart. Only on the day of his military committal at Santa Fe National Cemetery did we learn that he had earned a Presidential Citation for valor.

Ernie Springer during his time overseas in the Korean War.

Like most real heroes he remained tight-lipped about what he endured. Through sorrowful watery eyes six decades after the fact, he once simply remarked, “It was so cold.” I am entirely convinced that talking through trauma was not in his DNA. It was better to bury the memory of having to do the unthinkable to an enemy combatant.

The 2nd Infantry Division fought in rugged, mountainous terrain that typified Korea. Dad was wounded in action during a month-long battle known as “Heartbreak Ridge” when a grenade exploded in his squad. Dad got the least of it; one man’s leg was shredded, two other men lost their lives.

A month before Heartbreak, Dad fought through “Bloody Ridge,” a days-long affair where combatants faced each other at close range and the Americans did mop-up with flame throwers torching machine gun nests. The book Combat Actions in Korea, published by the U.S. Army, revealed that only 20 men from the 9th Regiment’s Baker Company survived it all. Dad was one of them.

Last year, I had the good fortune to locate one of the other 19 men from Baker Company. Though time erased any memory of my father, his brother-in-arms tearfully recalled their company commander. I learned that Captain Edward C. Krzyzowski heroically gave his life for his men on Bloody Ridge, and for that he earned the Medal of Honor.

Dad went from a soldier’s steel pot to an ironworker’s hard hat after the war, and he loved his work. To his last days he showed his fidelity; he identified himself in two ways: a 2nd Infantry Division soldier and an ironworker. He regularly wore a Korean Veteran hat or jacket emblazoned with the Union Ironworker logo.

Talon Noh, a young Seoul-born and naturalized-American pastor whom Dad admired, officiated his military committal at the Santa Fe National Cemetery. He read Psalm 23 from the very same snow-stained Bible that Dad carried in combat. Noh, referring to Dad as his “brother,” remarked that Dad had walked through “the valley of the shadow of death” with a rifle. He noted that without the sacrifice of Americans, there would be no South Korea.

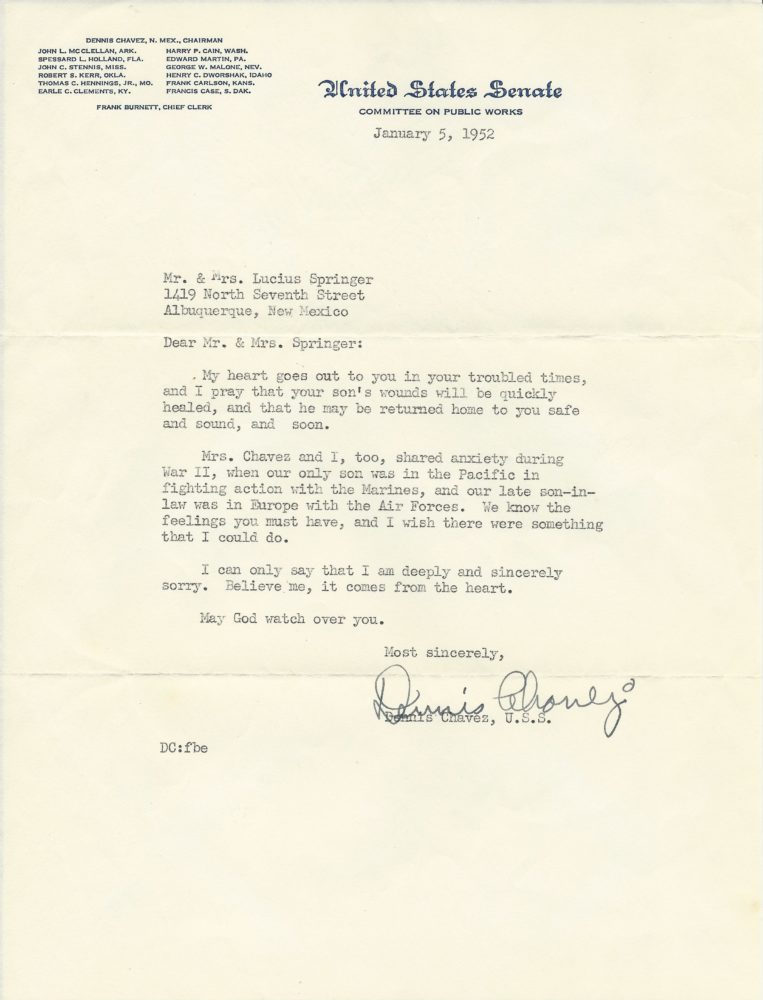

A newspaper clipping highlights Springer’s service to his country.

The sacrifice was large. According to the American Battle Monuments Commission, 54,246 Americans died in the 37 months of the Korean War; the number is engraved on the Korean Veterans War Memorial in Washington, D.C. The monument also has these words etched in polished stone: “FREEDOM IS NOT FREE.”

Dad was proud to have served in the 2nd Infantry Division, and he was a dad second to none. As another Veterans Day comes to pass, I remember this orphan of military history, “The Forgotten War,” and my father’s sacrifice in a special way.

Every work day I pass under a sign that reads “Dennis Chavez Federal Building.” It has become a mental habit to recall a poignant letter from January 1952 addressed to my grandparents. U.S. Senator Dennis Chavez offered condolences, wishing for Dad’s speedy recovery. By the time they had received the letter, their son was already back on the front lines in combat.

The letter Ernie Springer’s family received from Senator Chavez.

As a father of three children myself, Dad’s devotion to country, his work ethic and his love of the outdoors sit with me as guiding examples. There is no question time together outdoors with Dad steered me to a career in conservation, and I certainly had his encouragement to do so.

Those small spots of time we shared as father and son have become beautiful moments — moments everlasting.

You can learn more about the Korean War at koreanwar.org.

Editor’s Note: Craig Springer works for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in the Southwest region.