In one of his most fascinating chapters, he gives the reader an extraordinary glimpse into this creature’s remarkably terrifying and volatile behavior.

The winding road to Albert National Park between Lake Kivu and Lake Albert in Central Africa picks its way through lush vegetation, the occasional banana plantation and clusters of beehive huts. On the right side of the road is Mount Mikeno, a volcanic peak that soars 14,557 feet above the jungle where in the swirling mists that shroud its head, it broods like an unhappy ogre. Through glasses one can just make out on its slopes the great belts of dripping bamboo, chief food of the last of the world’s gorillas. If the mists lift, one can also see the spot where they buried Carl Ethan Akeley.

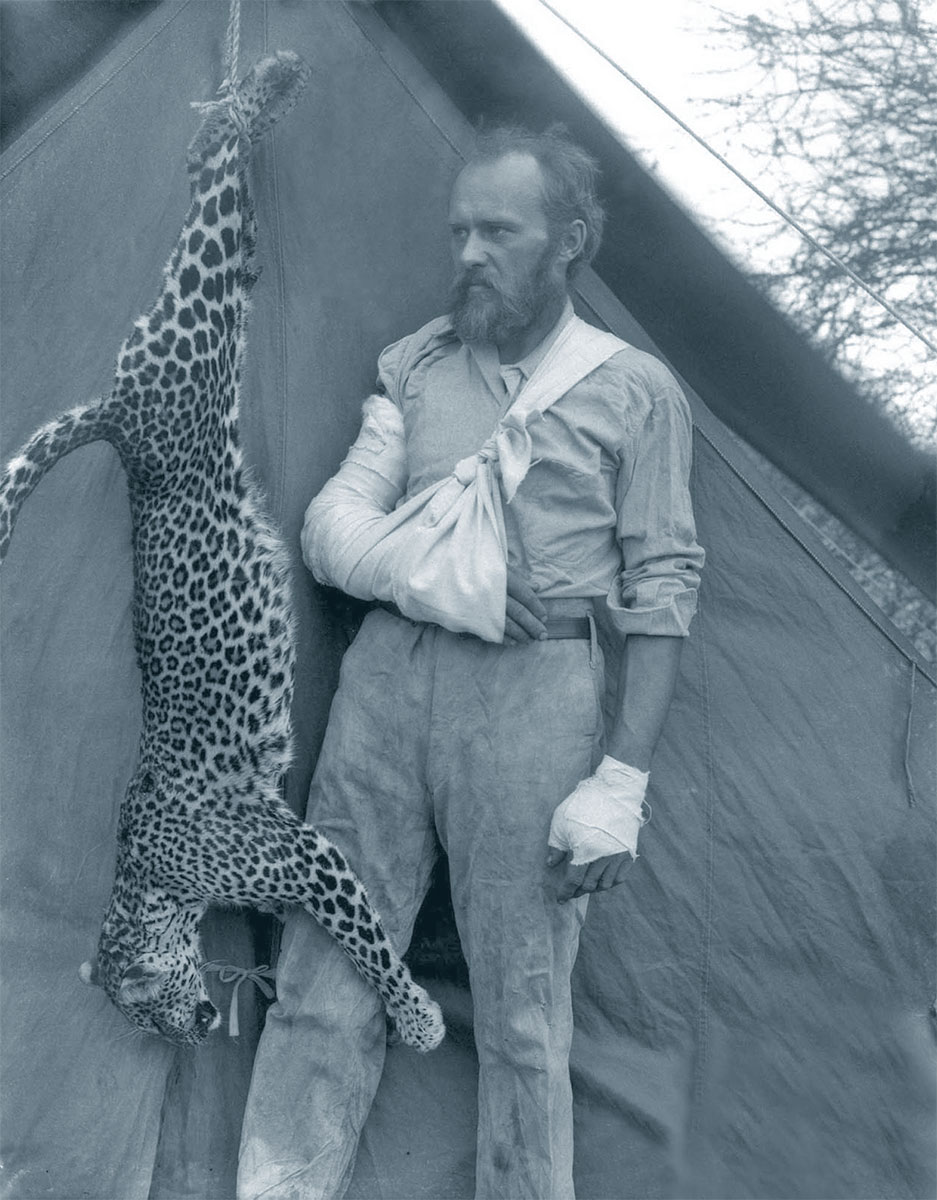

A sculptor, taxidermist and naturalist, Akeley was an American by birth and an African at heart. He made five visits to Africa to collect and to observe. On his return to America, he organized the mounting of some of the world’s finest wildlife museum exhibits, including one tableau of an entire family of elephants. It has been said that his imaginative handling of museum exhibits ended the era in which taxidermy was something akin to soft-toy stuffing.

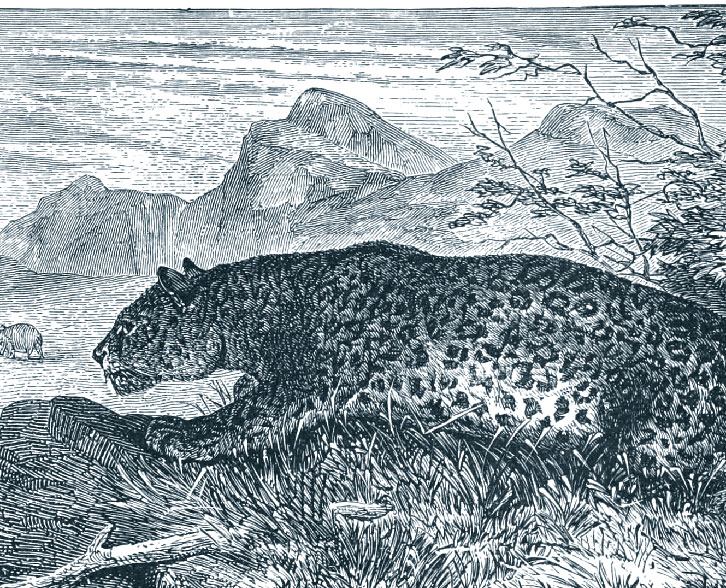

A heavily bandaged Carl Akeley stands next to the leopard that he strangled to death after it attacked him at point-blank range.

Akeley died a natural death at age 62 in 1926, but twice he had cheated death—once when an elephant badly mangled him and once, in 1896, on his first visit to Africa, when a wounded leopard charged him at point-blank range and sent his rifle flying. Caught completely by surprise when the cat came at him, he had time only to throw his arm up in front of his face. The leopard seized his arm in its teeth and began clawing at him with its front paws. Akeley, with his free hand, grabbed the cat around the throat and held it away from his body, his main concern being that the leopard might bring up its back legs and rip him down the middle. Leopards occasionally use this tactic, though in most attacks they prefer to latch on with their front claws and then tear with their teeth.

The taxidermist tightened his grip on the cat’s throat and slowly worked his arm out of its mouth every time he felt its jaws relax. Soon, only his fist was in its mouth, which he kept there so the leopard could not bite his face and head. Akeley then deliberately fell on top of the animal and dug his knees into its rib cage and his elbows into the leopard’s armpits to force its flailing front feet apart. Slowly the cat went limp. By the time Akeley rose, the leopard was dead. It had died from strangulation, and its ribs were cracked from the pressure Akeley had exerted.

Akeley’s escape is by no means unique—wounded leopards, ferocious though they are, rarely manage to kill their human victims and usually end up running away.

The leopard, whether it is hunting along the nullahs of India or on the African veld, is a veritable Jekyll and Hyde. Unmolested and in normal health, it is a shy, almost nervous animal with a very marked fear of man. Unlike the lion and tiger, both of which move out of man’s way with aplomb and dignity, the leopard will usually run, perhaps pausing to cast a quick glance over its shoulder. Should you make a sudden movement, the cat will spring into the nearest thicket and then flee like a startled hare. Many are the stories that speak of the leopard’s apparent lack of spirit.

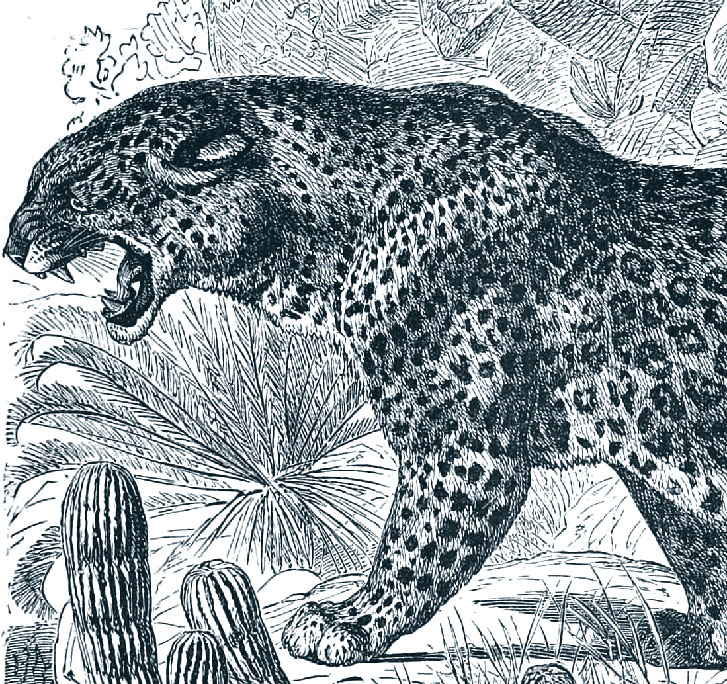

But when a leopard is wounded, trapped or cornered, it is an entirely different animal. Indeed, there is no other animal in the world more likely to attack when wounded, and many hunters believe there is no animal more desperate or savage.

Stevenson Hamilton described a wounded leopard at bay as “the very incarnation of ferocity; his ears are laid back low against a flat-looking head, his long white teeth gleam between withdrawn and snarling lips, while his eyes, fixed with a steady and sinister stare upon his enemy, are filled with dull, greenish-red light that shows murderous hate. Even when you know his back to be broken, his appearance is so little assuring that you have qualms about approaching close enough to administer the coup de grace.”

Before we look at the leopard as a man-killer or as a man-eater, let us look at him under happier circumstances, unmolested in his natural habitat. Panthera pardus is the most graceful and beautiful of all the big cats and is found throughout Africa, from the Cape of Good Hope to the shores of the Mediterranean, including the jungles of Central Africa, where the lion is absent. It is found thinly distributed in Asia Minor and then is more densely distributed in western Asia and in the Far East to the Chinese seaboard and down to Java. An estimated 6,000 to 7,000 leopards live in India. They are also found in Ceylon, where the tiger is unknown. Technically, the leopard is extant in Europe, for a few are said to survive in southeast Russia and, if so, these would be descendants of the leopards that hunted Europe during Pleistocene times.

Throughout this vast area, the species remains the same with only sub-specific differences, which are mainly in size and coloring but which to the layman would hardly be noticeable. The panther of India is precisely the same as the leopard of Africa, and the Asian “black panther” is merely a melanistic leopard that is capable of throwing off normal, spotted offspring. The “tiger” of South Africa is also the common leopard.

The animal is inclined to be a little on the stocky side when conditions are favorable, but never so much that it loses its graceful appearance. It weighs an average of 100 pounds or slightly more, and a really heavy one in the wild might go as high as 160. The record length is nine feet, which is not far off the record length for a lion—but a third of a leopard’s length is tail.

It is strange that a creature so well equipped in tooth and claw, so given to fierce attacks when wounded, and so capable of lightning action should, at the same time, find it difficult to overpower a man. (I am referring to the “incidental” attackers such as freshly wounded leopards and not to confirmed man-eaters, which are a different kettle of fish entirely.)

The leopard certainly doesn’t lack strength. T. Murray Smith saw a 150-pound leopard kill a 90-pound antelope, carry it in its jaws “like a dog carrying a hare,” and then climb 30 feet into a tree with it. This feat is by no means unusual, for leopards frequently carry their prey into trees out of the reach of hyenas, jackals and lions. There is a record of one carrying a 200-pound baby giraffe 12 feet up a tree.

Why then does the leopard not employ this strength when tackling a man? I can only believe it is because it relies upon fast claw work and biting to overcome its victim—unlike the lion and the tiger, which often kill by cuffing their victims. And it might be partly due to the leopard’s streak of cowardice. Perhaps cowardice is not the right word—the leopard’s fear of man could be a mark of its intelligence and, along with its strictly nocturnal habits, is one of the chief reasons it has survived within sight of large cities.

This apparent feeling on the part of the leopard that discretion is the better part of valor is often manifest when the cat is attacking a baboon troop and runs into a big male.

I once watched such an incident. A dog baboon immediately attacked the stalking leopard, and screaming at the capacity of its lungs, it tore at the cat’s neck and shoulders with its long canines. The leopard, spitting and snarling, rolled in the dust with the baboon and then withdrew and tried to “box” the animal with open claws. But the baboon knew better and once again closed in and began biting. After perhaps a minute, the big cat disengaged itself and fled, leaving a badly torn baboon licking his wounds.

In the old days, a good 75 percent of people mauled by leopards died from infection caused by the rotting meat between the leopards’ toes. According to one researcher, the incidence of infection from leopard wounds is higher than with tigers. With the advent of penicillin, deaths were cut down to less than 10 percent of the people mauled.

Going by the very inadequate statistics available from local authorities and wildlife organizations, and mainly from incidents reported in newspapers, leopards probably cause a minimum of 400 casualties a year. Of these, only a quarter would be due to man-eaters and the rest to the work of wounded or cornered leopards.

Of the remaining 300 victims of “accidental” skirmishes, only 10 to 15 percent die of their wounds and, in most cases, the leopard is either shot or killed by hand.

On the basis of these figures, there must be upwards of 10,000 people alive in the world today who bear the scars of a fight with a leopard.

In 1960, according to these reports, three leopards were killed barehanded, one of them by a 70-year-old, gray-haired Rhodesian named Kudziburira, who took his dog and an axe to look for a leopard that had killed one of his goats in Sinoia, Rhodesia. The dog flushed the leopard and was immediately killed, and the cat then turned on the old man, who in his fright dropped his axe. The leopard went for him and bit into his left arm, which he had thrown up to protect his face. The man gripped the cat by the throat with his free hand and held it there until he felt its jaws relaxing. Then, pulling his arm from its mouth, he put both hands around the cat’s neck and half-strangled it. He let the leopard fall into an unconscious heap before he picked up his axe and delivered the death blow.

Two months after this, a Portuguese man in Mozambique was attacked by a wounded leopard, which he managed to strangle, and not long after that, another Portuguese man strangled a leopard with his bare hands at Silva Porto in Portuguese West Africa, just north of South West Africa. In all these incidents the men were severely mauled.

There are scores of incidents on record of men strangling or choking leopards and, in at least one recorded incident, the man killed two leopards by crashing their heads together. The man who performed this feat was Cottar, a Texan who became a white hunter in East Africa and who, according to J.A. Hunter, killed three leopards barehanded in his career.

In India, leopards also occasionally find the tables turned against them. In July 1963 there was a remarkable story from Calcutta about an elderly woman named Debku who, in the state of Himachal Pradesh, throttled a leopard after an hour-long struggle during which her dogs kept worrying the cat.

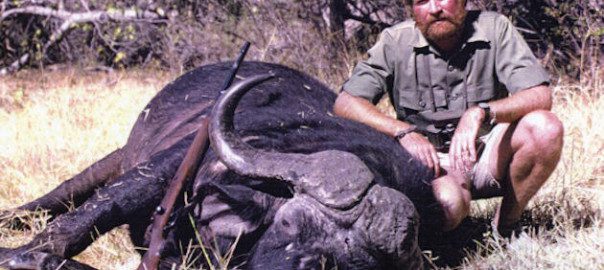

Significantly, many hunters class the leopard as the most dangerous of all the big game animals to hunt. Ionides considered it the most dangerous animal in the world, and Rushby classed it as more dangerous when wounded than a wounded buffalo. He described the leopard as “a perfectly built killing machine” and said that as a target, it was so small and so fast that it was most difficult to hit. To make things doubly difficult for the hunter, the leopard specializes, a little like the tiger, in short-range charges. But, in spite of all the claims from hunters, I cannot think of a single big game hunter who was killed by a leopard. Some may well have been, but the number must be insignificant.

There is a theory that a leopardess will charge a man on sight if she has cubs with her. Ted Reilly of Mililwane Game Sanctuary, Swaziland, told me how he once came across a leopard cub in the bush, and assuming it was orphaned or abandoned, picked it up. Even as he straightened up, he could sense danger, and as he held the spitting bundle in his arms, he found himself looking into the smoldering eyes of a she-leopard. Reilly, being alone and unarmed, fairly jumped out of his skin. His involuntary movement caused the mother leopard to turn and flee. This behavior seems to be fairly unusual, but it does illustrate how highly strung these animals are in the presence of man.

An Acholi game ranger in Queen Elizabeth Game Reserve in Uganda was not so fortunate the day he cycled past a leopard cub. He guessed the mother would not be far away, so he pedaled harder. The next thing he knew the mother was pelting in behind him and sprang onto his back, where she remained firmly latched as the ranger put on an admirable burst of speed. The leopard fell off 200 yards farther along.

A similar incident befell Arian Suque of Dodoma, Rhodesia, in 1964, when a mother leopard with three cubs attacked him and pushed him off his bike. Suque fought the leopard and she ran off, but a minute later she came back for another round. Again Suque fought her, and again she retreated. But this was an occasion when the leopard came out on top: She punctured the African’s wheel, and he had to walk ten miles to a hospital.

At the state opening of Kenya’s Parliament in 1963, Senator Godfrey Kipbury, the Masai member of the Senate, made a grand entrance wearing a smelly leopard-skin hat. It smelled because the skin was only 48 hours old. The senator had speared the leopard on his farm but was clawed in the process. Annually, scores of leopards are speared by Africans mainly because of their threat to livestock.

Although India, through the writings of such men as Jim Corbett, has received more publicity for its man-eating leopards, Africa’s record is as bad. Throughout its range, when a leopard does turn man-eater, it goes mainly for children and sick adults, and sometimes it has even dragged humans into its larder in the branches of trees. George Rushby, who was senior game ranger in the notorious Njombe district of the Southern Province of Tanzania, said that at least 15 Africans a year were eaten by leopards there during the 1950s. Oddly, most of Africa’s man-eating leopards have been in Central Africa. I have come across no instance of man-eating leopards at all in South Africa, and there are few in East Africa, but in Central Africa man-eating leopards have caused entire villages to be abandoned. Some leopards are crippled or old, and one feeble old cat that killed 22 people in northern Mozambique was even too weak to carry off its victims. It used to tear chunks out of them and then limp away into the night.

C.J.P. Ionides describes the depredations of a typical man-eater that haunted Rupenda, Tanzania, in 1950. This leopard might have been forced into eating man because of the ill-fated British Groundnut Scheme. Africans had been clearing the bush for miles around for the scheme, and the leopard’s natural prey had entirely disappeared. The leopard began by killing a laborer, but before it could eat him, it was beaten off by villagers. That same night, six miles away, it ate a baby after stealing it from its bed.

Two days later, it hid behind some scrub and watched a mother teaching her toddler to walk. Then, when the mother went indoors for a few seconds, the leopard snatched up the child and later ate it. A third and fourth child were taken near Rupenda before Ionides got to the village and then the leopard struck a fifth child seven miles away. Eighteen children were taken in a few months; the youngest a 6-month-old baby and the oldest a 9-year-old girl. The killer was eventually caught in a trap.

Leopards will often kill humans apparently for the sake of killing. One of the most notorious in this regard was the leopard of Masaguru, Tanzania, on the Ruvuma River. It killed 26 women and children, not one of whom was eaten. Rushby says that not even a bite was taken from them and, when it was finally shot, the killer cat was found to be in good shape. Possibly the leopard had taken a liking to drinking human blood, for this has happened from time to time.

Rushby has an interesting theory about man-eating leopards and surmised that they eat humans merely for variety. He points out that even as man-eaters, they continue to kill and eat monkeys and baboons. In fact, says the hunter, there cannot be much difference between human meat and monkey meat.

There there have been some incredibly successful man-eaters in India. The Panar leopard is supposed to have eaten 400 before it was shot a generation ago by the legendary Jim Corbett. The man-eater of Rudraprayag ate 125 during roughly the same period. More recently, the man-eaters of Bihar state in 1959 and 1960 are said to have killed 300 people. There are so many more: the Gummalapur man-eater, shot by Kenneth Anderson, and a host of others that have plagued the wild and beautiful valleys of central and northern India. In centuries gone by, the record hardly varied. Oddly enough, man-eating leopards are almost as rare in southern India as they are in southern Africa—except in the narrow, 400-mile-long forest belt in the Western Ghats.

Man-eating leopards in India kill a significantly greater number of victims than their counterparts do in Africa. One reason is that the man-eaters of India seem to survive a great deal longer than the man-eaters of Africa. But this is only half the answer. Is it perhaps because the Indian hunter is less persistent and bold when pursuing man-eaters than the African hunter?

Jim Corbett, the man who shot both the Rudraprayag and Panar leopards, puts it down to the way Hindus, in times of plague or famine—when there is no time to bury their dead as they normally do—put a piece of coal into the victim’s mouth and leave the corpse in the bush. Leopards, always partial to a little carrion, eat these bodies and acquire a taste for human flesh.

This is not an entirely satisfactory answer, because in Africa, tribesmen in many parts habitually leave their dead in the bush for scavengers. This does create man-eating leopards, but none has ever approached killing the numbers claimed by the big man-eaters of India.

The character of a man-eating leopard differs from that of the mauler. Man-eaters show no ill temper but instead, hunt with awesome calm and cunning. In India, as in Africa, most of them specialize in children, and E.P. Gee speaks of one that ate only children between 6 and 10 years of age. Because of the leopard’s strictly nocturnal habits and its custom of hanging about on the outskirts of villages in the hope of knocking down stray livestock or dogs, the Indian leopard is familiar with the ways of men. To add to its efficiency as a man-killer, it is always supremely cautious, never really losing its fear of man, no matter how many men it has eaten.

When, in 1910, Jim Corbett was called upon by the Indian government to hunt down the Panar man-eater, he made straight for the area, which was not very far from where he lived at Naini Tal in northern India. Questions were being asked in the British House of Commons about the killer, for it was haunting the same area as the infamous tigress of Champawat. Between them, the two cats killed 836 peasants, enough to populate a small village.

Until Corbett made a move, no other hunter had heeded the government’s appeal for somebody to kill the animal. The peasants’ reaction, as always, was to barricade themselves in at night—and even during the day when they could. This often forced the Panar man-eater to tear down doors or burrow into grass roofs to get at the occupants.

On Corbett’s first day in the leopard’s hunting area, he met a dazed and frightened young man who staggered from his lonely farmhouse and told the hunter how the night before, the leopard had climbed over his balcony, stolen into the bedroom and grabbed his 18-year-old wife by the throat. The poor woman had screamed and then flung an arm around her husband, who held on and played tug-of-war with the cat. The leopard let go and retreated, enabling the husband to slam the door and hold it shut while the leopard, gaining new courage, tried all night to tear it down. The woman huddled in a corner until at dawn she lost consciousness. The husband was too frightened to face the mile-long journey to his nearest neighbors.

Corbett saw the woman and noticed that her wounds—tooth punctures in the throat and four deep claw marks on her breast—were now septic. The room was windowless and filled with flies. The hunter was faced with the choice of going for medical aid, which was several hours away—for what he knew was a hopeless case—or hunting down the leopard while it was still in the area. He elected to wait for the return of the leopard, but he waited in vain. The woman died.

The month was April, and Corbett was forced to abandon the hunt until the following autumn. In September, the leopard was still eating humans at an alarming rate. In the space of a few days, it had eaten four men, one after another, in the same patch of brushwood. The villagers, not having a firearm, had allowed the leopard to finish its meals undisturbed.

Corbett decided to bait the leopard with a goat tied to a stake while he balanced himself on a tree branch 30 yards away. The leopard came, but showed no interest in the bleating goat; instead, it tried to climb the tree to get Corbett, who had taken the precaution of surrounding himself with thorns. He managed to shoot the leopard but succeeded only in wounding it. Later, with reckless courage, he sought it out by the light of a flaming torch and killed it.

Few of India’s notorious man-eating leopards have shown signs of injury or old age, signs which might have explained why they suddenly took to man-eating. True, Kenneth Andrson’s Gummalapur man-eater was found to be lame, and his “Sangam panther” was old and decidedly worn in the tooth, but mostly they were in good health.

It is significant that the Panar and the Rudraprayag man-eaters followed hard on the heels of cholera and Spanish flu epidemics.

The pilgrimage to Badrinath in the rugged, deeply forested Garhwal district of Uttar Pradesh in northern India is long and arduous. Annually for 2,000 years, tens of thousands of Indians have climbed to the shrine of Badrinath in the temple on the shoulder of the 23,420-foot Mount Badrinath. The pilgrimage has always been a tough one and is only for the really devout. Between the years 1918 and 1926, it was particularly arduous because the 60,000 pilgrims who trudged each year along the narrow, winding paths knew that watching their thin, straggling line was a leopard: the man-eater of Rudraprayag.

Occasionally the leopard would take a pilgrim, but mainly, it contented itself by coolly and calmly snatching villagers who ventured out at night. If it grew impatient, which was often, and if no villagers showed themselves, it would then pad silently between the huts until it saw a door weak enough to tear down.

Sometimes the leopard found open windows or groups of pilgrims sleeping in the open, and then it would swiftly and soundlessly sink its fangs into a sleeping victim and carry him away, often without disturbing those who were sleeping nearby. For eight years, 50,000 villagers lived in terror and observed a strict curfew that under any other conditions might have been intolerable. For eight years, a fearful silence settled over the villages after sunset, for each inhabitant believed the leopard was listening outside his door.

The government appealed to hunters and employed India’s finest shikaris at elaborate fees, but the man-eater was too cunning, and the men who hunted it became infected by the villagers’ dumb terror. Even though there were something like 4,000 licensed guns in the district, the government granted 300 more, just to aid the hunt. But although the footprints of the hunters in the deep, echoing ravines often obscured the pugmarks of the man-eater, the Rudraprayag leopard carried on undaunted.

The government offered 10,000 rupees to the man bold enough to kill the cat but there were no takers. None—except Jim Corbett.

The hunter’s first attempt failed. This was due mainly to Corbett’s own ill health and partly to the superstition of the villagers, who by now believed that the leopard was supernatural. Then, on May 1, 1926, Corbett, using a goat as bait, shot the leopard dead. It was an anticlimax in a way. The official death toll was 125. There have been worse leopards before and since, but somehow none has ever achieved the same notoriety or instilled the same degree of terrorism.