Mind-boggling numbers of mallards, mallards like blackbirds, tornadoes of mallards, more mallards than sky.

Way down in October, in The Moon of Falling Leaves, me and Joe Merganser on the back loading dock of the farmer’s co-op elevator. Joe Merganser was full-blood Ojibwe. Hard to find a full blood even then, no-count squaw-men marrying to get a claim on reservation land the way they did. Two hundred and fifty miles from Minneapolis, north by northwest, another world, another time.

Population 1,859, ten blocks wide, 20 blocks long, where the train did not stop and the bus never did. The elders gathered on the post office steps, conversing in Norwegian and Finn, adjudicating the rise and fall of sow bellies as reported on KFGO, Fargo, North Dakota. Co-op electric company, co-op feed mill. A note above the time clock at the co-op gas station read: “All employees are requested to take a shower before reporting to work, as it is necessary to kiss your ass to get you to do anything at all.”

The loading dock broke the wind, and the sun on the tin melted the snow on even the bitterest days. Joe would cut and split firewood, till a garden, butcher chickens or a hog as the spirit moved, Phillips blackberry brandy being the coin of the realm. When Elmore Pladsen passed, Zion Lutheran hired Joe to dig the grave. Poor Elmore’s casket lay in public view three days. When the elders finally caught up with Merganser, he said, “You just hired me to dig the grave.”

I was negotiating a transaction and offering a retainer when there came a mighty whistling on the wind. Joe looked up and squinted at the bright pewter sky, pointing with his nose like Indians do. “Dabazo,” he said in Ojibwe. “Ducks.”

Not just ducks but mallards, curly-tailed dippers, a flock of a thousand or more, knotted up and headed west, low enough so you could hear the quacking. This was where the rocky hills dropped off to pool table prairie, where the glacier made one final swipe ten thousand years before; lakes to the east, grain to the west. At the top of the Mississippi Flyway, there was often as much east-west traffic as north-south. But I had never seen anything like this.

“Many more,” Joe said. “Every day this time.”

“Must be a sign,” I said.

“Yes,” Joe smacked his lips. “Say, ‘go like wind to liquor store.’”

I slipped him five bucks.

I fueled the Ford, went to the body shop, and rounded up Brush Wolf, a Bohemian from Biwabik, a name you can’t say drunk, which is just up the road from Bemidji, a name you can’t say sober.

“Grab your binoculars, Brush Wolf, and come with me!”

Those were the days before the government mandated paint booths in the shops, and Brush Wolf was like most body men, always eager for a breath of fresh air. If a man kept at it 15, 20 years, he would wind up drunk as Joe Merganser. If a body man didn’t drink, the paint fumes would give him the colic.

So we chased mallards the rest of the afternoon, trying to figure out their ways. They came on the wind in knots thick as diesel smoke, a thousand at a crack, knot after knot after knot, then swung upwind to land in the stubble. Waddling along as fast as a mallard could wobble, gobbling wheat and barley to the left and right, whatever the combines missed. By and by the back mallards thought the front mallards were getting the better pickings and they would take wing and fly over the front mallards until the former front mallards, suddenly the back mallards, figured they were getting shorted and would do the same. Ever see ducks playing leapfrog? We saw it that afternoon by the tens of thousands.

Brush Wolf glassed them long and hard, his elbows on the open pickup window to steady the view. Open country thereabouts, with ditches every mile upon the mile, checkerboard square. Red and black willows in the ditch bottoms, a few lonesome cottonwoods, no place to hide.

“Look at dem silly bastids,” he said in his heavy Bohunk brogue. “Dey vill be easy to get on.”

His grandpa came to Minnesota a hundred years before to work the ore pits along the Mesabi Range. Mesabi iron built the ’53 Buick, the ’57 Chevy, locomotives and Liberty ships.

“Oh yah, up on da St. Looey after freeze up, veed shuvel a barrel of snow and den build a fire under it, and ven it vas tawed out, trow in a pack of blue dye. Veed dump dat on da ice and da ducks vould tink it vas open vater.”

“We damn sure can’t do that here, Brush Wolf.”

“No, but you got black plastic, don’t you? Dat vorks da same. Ve’ll poot in in dat low spot yonder. And den ve vill vait it down vit decoys.”

It was a good idea, but it didn’t work. Out slogging around the plowing before dawn, I unfolded a piece of black construction poly about 40 by 100 feet. Brush Wolf plopped decoys here and there, with congregations at the corners and along the edges to keep the wind from rolling it up. We lay beside it, flat on our backs in the wet and pungent dirt. The first flock roared in like artillery, so low we felt the wind on our faces. But they kept going. So did the second and the third.

“What in the hell are you boys doing in my field?”

That was a couple of hours later, the sun two handbreadths up the sky. He was leaning from his pickup window, trying to make sense of the spectacle, me and Brush Wolf, bloodshot and muddy, one miscreant struggling a shotgun and a G.I. duffel bag bulging with decoys, the other with his shotgun trailing a long, battered train of black poly, like refugees from the Siege of Stalingrad.

You dassn’t open a gate, cross a fence or standing crops, and we hadn’t. Farmers were generally too busy to hunt anyway, though eventually they realized there was money in pheasants.

“I’m sorry, sir. I hope you don’t mind. We were just trying to shoot a few ducks.”

“Ducks?” he laughed. “Ducks? Let me tell you about ducks! Those pirates at the co-op elevator docked me forty-two cents per bushel of barley! Forty-two cents! That’s forty-two cents times ten thousand bushels! And do you know why?”

“No sir, why?”

He spat out the window. “Duck crap! There was that much duck crap in the swaths!” Then, as an afterthought, he added, “Goose crap, too, of course! You want ducks, you follow me!”

“Well, that’s mighty nice of you, sir, but I’d like to change clothes first.”

We were upwind, and he caught our scent. He wrinkled his nose, curled his lip.

“Peterson, Pete Peterson, third place on the left on that section road yonder. Name’s on the mailbox; Peterson with an O. First two places are Petersens with an E; don’t bother them. You smell bad? They raise feeder calves. Be back about four.”

And then he rattled away, and damn, that shower felt good.

We were at his place at the appointed hour. He walked us behind the machinery shed and pointed to the southwest. It was open country, the flattest of the flat, so flat a man might swear he saw the curve of the earth along the edge of the sky and distant barns looked like ships sailing on an ocean of grass.

“Beaver plugged a culvert and flooded out sixty acres of corn. You want ducks? You’ll have ducks before sundown.”

The water was knee deep and the footing was good. But once again, no place to hide way out there in that raggedy, windblown corn stubble. We were trying to figure out our next move when the ducks were suddenly upon us and there was no more time to figure. A cloud of ten thousand, likely more, swirling, pulsing like a single being and roaring like a tornado. We did the only thing we could do; we sat on our bony fannies in the chilly Minnesota water, tucked our heads, laid our guns across our knees. It hurt.

Hard to fool a mallard, but we didn’t have to. There just wasn’t enough sky for all of them. They circled clockwise, and when they spied us and tried to turn, there was outraged quacking, bone beating upon bone, wing slapping wing, pop, pop, pop, the outer rim of the avian escadrille in easy gun range. Three times they circled and three times we shot. By the fourth pass we had our limit—six each, all drakes.

Pete Peterson met us in the barnyard. “Good job. Why’d you quit?”

“Da limit,” Brush Wolf said, proudly hefting his birds. “Ve got da limit.”

“Limit? Limit?” Pete Peterson fumed. “Who said anything about limits?”

He spit and squinted off toward the flooded corn, black now with feeding birds.

“No limit on duck crap in my grain! I was good enough to put you boys on these ducks. And this is how you repay me? Get the hell off my land, and don’t come back!”

“Jeepers, creepers,” Brush Wolf said. That was a mile or so down the road, the sun and daylight slipping away. “You tink ve can get da Indian to clean dem?”

“Maybe,” I said. “He owes me five bucks.”

We looked till dark but never found him.

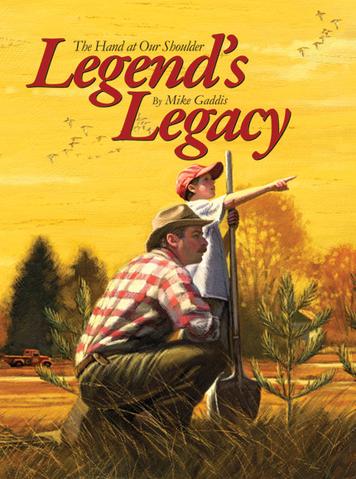

There was a time when the world spun more gently, when family was the axis of its existence and folks lived closer to the land. A time when a gun was no less valuable to the scheme of being than a Bible or a blade, when a hunting dog could be found under the front porch and a fishing pole sat ready in a chimney corner.

There was a time when the world spun more gently, when family was the axis of its existence and folks lived closer to the land. A time when a gun was no less valuable to the scheme of being than a Bible or a blade, when a hunting dog could be found under the front porch and a fishing pole sat ready in a chimney corner.

There was an age, a space of innocence, freedom and fascination, where every day brought another revelation, and tommorow could never come fast enough. When, as boys and girls, we learned as much from woods and waters as from a spelling book.

Most of all, there were moments of infinite beauty and sharing, when someone laid a hand at our shoulder and led us there. So that later we might lead another, in turn.

Here, in parables of incomparable warmth and intonation, the author of the celebrated books, Jenny Willow and Zip Zap, explores the enchanting realm of outdoor mentorship. Not only in kind and gentle remembrances, but in intuitive vignettes, present and future.

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still. Buy Now