“Come get me!”

He found me a garage on an alley behind a mansion on Summit Avenue, just down from the governor’s mansion, just down from the bar where F. Scott Fitzgerald fell off many a stool. But before I could dig out my wrenches, he said, “Rog, let’s fix this thing tomorrow. I got a party this evening. Why don’t you come along?”

Why not?

More Swedes in St. Paul than in Stockholm. There was this fetching, green-eyed, redheaded thing.

“Hey Honey, are you a Swede?”

She flashed me a million kroner smile. “I’m half Swede and half German.”

“Well, which half is Swede?”

Another smile, this one punctuated with a not-so-shy wiggle. “The best half!”

Oh, Lordy.

Small wonder it took me 20 years to get back on the road.

Six months in downtown St Paul, just off West Seventh, at the foot of the old steel High Bridge across the Mississippi, groaning and trembling and contracting at midnight when the mercury dropped and the traffic slacked off. From thence to an Anoka County farmhouse made of old Soo Line boxcars.

“Anoka” is an Indian word meaning “on both sides of,” as the Ojibwe could not comprehend why the White Man would build a town on both sides of a river, where he would need a boat or a bridge to visit his neighbors or procure a jug of Old Tangle-Foot firewater. And finally, I moved to a pioneer log cabin on 80 acres in Otter Tail County where a man might throw a cat through the cracks in the chinking.

But I digress.

There were cornfed white-tailed deer in Minnesota, lots of ’em and a nice buck would tip the scales at two-fifty, walking weight. I had no proper deer rifle, hailing as I did from a country where we drove deer with horses and hounds and hammered them on the run with buckshot thrown from fine old long-barreled double guns.

Minnesota permitted slugs, required them in some locales but a double gun will not handle slugs to any satisfaction. Deer dogs were prohibited outright and a horse was considered a motor vehicle and all firearms transported thereupon had to be completely cased. And no, a pistol holster was not a legal case, which is no doubt why Jesse James and company got into so much trouble when they rode into Northfield with their Colt six-shooters in September, 1876.

Forewarned, I set out to find suitable alternative armament.

It was a M-94 Swedish Mauser, originally a cavalry carbine, 17-inch barrel, Herter’s stock and Weaver K-4 scope in 6.5×55. A long noodle of a round-nosed bullet at about 2,500 feet per second, it was perfect for woods work. Deer or bear, I became notably proficient with it.

Sporterized Swedish Mauser

A typical after-hunt conversation at the Loon’s Nest Café in Vergas, population 462, over hot roast pork sandwiches went like this: “Yah, Pinkerney, how did you do den?”

“Fat eight pointer.”

“You Mauser-ize him?”

“Yah.”

A Minnesota hot roast pork sandwich is two pieces of white Wonder Bread, an inch-thick slab of pork in between, a side of mashed potatoes and a pint of salty brown gravy slobbered over the whole God’s-thing. With another side of cooked-to-a-fare-thee-well green beans and everything loaded up with a healthy dusting of black pepper, it tasted a lot better than you might suspect.

Two desperadoes tried to rob the Vergas State Bank, just down the street from the Loon’s Nest Café, one minus-zero morning in December. Henry Iverson left his pickup idling in his driveway, heater on high, as he usually did, as everybody usually did, so he might drive down to the Loon’s Nest for coffee in comfort. The desperadoes figured it would make an excellent getaway vehicle, ditched theirs, stole his, left it running outside the bank while they went inside with pistols drawn. Meanwhile, Knute Knutson chanced along.

“I vonder vot Henry Iverson’s pickup is doing dere vid-out Henry?” He drove it back to Henry Iverson’s and left it running in the driveway as before. When the desperadoes backed out of the bank, they suddenly found themselves on foot. They bolted and hid in a snow-covered cattail slough just west of town. The cops never even gave chase. They just sat in their cruiser overlooking the slough, heater on high, till sundown when the frostbit desperadoes were more than happy to turn themselves in.

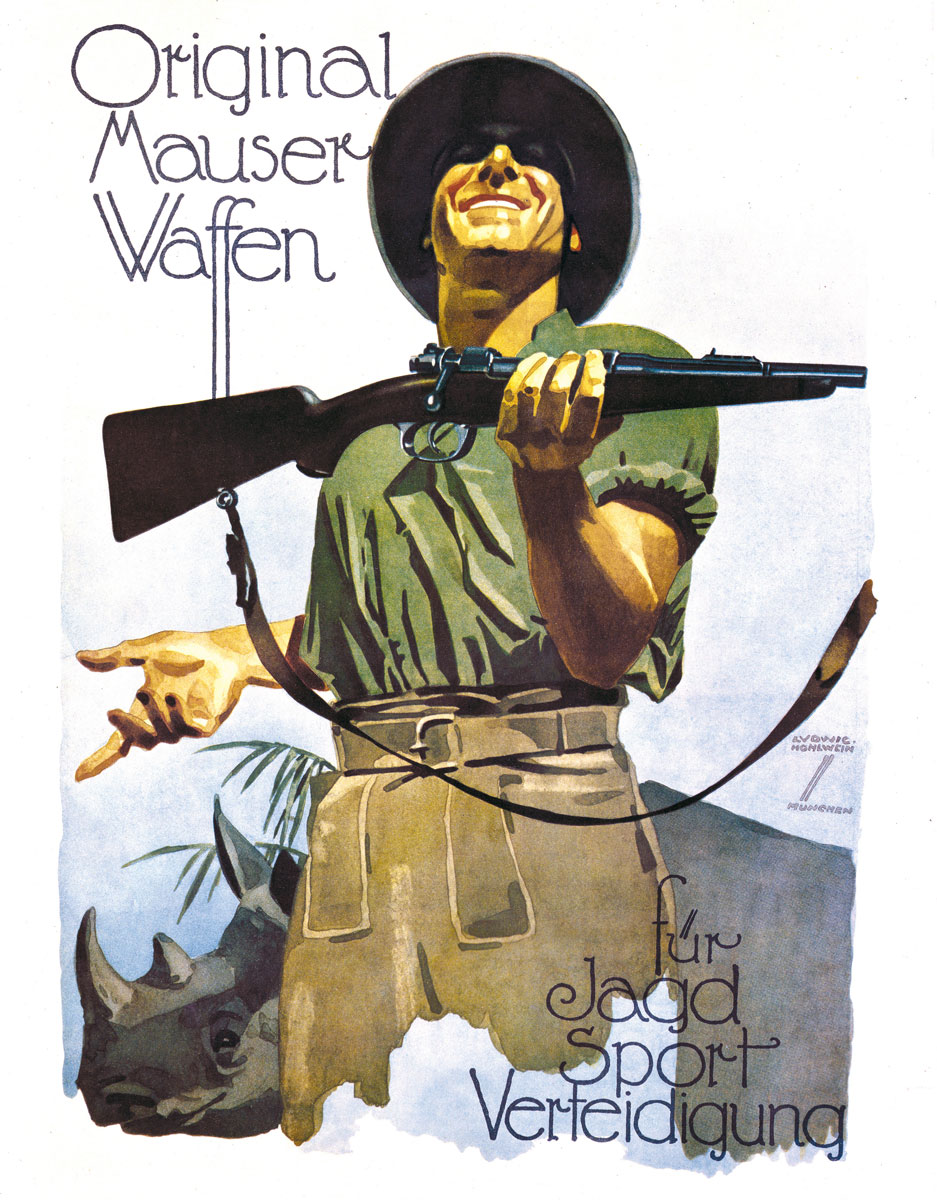

The Mauser System was the work of two German brothers, Peter Paul and Wilhelm Mauser from Oberndorf, sons of a noted German gunsmith. Beginning in 1871 with a turn-bolt magazine rifle for the Prussian Army, the brothers revolutionized firearms design at the dawn of the smokeless powder era.

There was the 1893 for Spain that gave Teddy Roosevelt fits at the base of San Juan Hill, my 94 Swede carbine, the 95 for the Chileans, Mexicans and Boers, the 96 for the Swedes again, and the crown of creation, the 98 for the Germans, Slovaks, Turks, even the Chinese. Altogether, ten million rifles were produced by Mauser or under license by others and associated civilian variations upon it that were sold to sportsmen worldwide, especially African settlers and safari hunters where the Mauser’s robust reliability could easily make the difference between supper and brutal death. The famed U.S. Springfield Rifle of 1903 so closely resembled the Mauser 98 that the Germans sued the U.S Government for patent infringement—and won a quarter-million dollars.

M98 Magnum Mauser

My deer hunting mentor in those days was Gerald Grahn, son of Erik Grahn, the Swedish immigrant. There was Gerald, Albin, Elsword and Ronald. Gerald milked Holsteins and played polkas on the accordion at all hours; Ronald milked Jerseys, walked around in ragged overalls with his bare ass hanging out; Albin brandished a crippled arm and liked to brag about all the times his bulls had tried to kill him; ditto Elsword who ran a sawmill. Neighbors shook their heads. “Vere it fell, it fell deep,” they said.

Gerald shot a Swede rifle, too, a commercial Husqvarna Mauser in .270. He called me about noon one opening day. “Pinkerney, you got your buck hanging?”

I did.

“Vell, can you help me wid mine? He’s a leetle too heavy for me to handle myself. I’ll come pick you up.”

The buck was a monster, 10 points, piled up in a thick grove of prickly ash. Gerald had cut off the nut sack but had not field-dressed the deer. I snicked open my field blade, a heavy, brass-trimmed folder, re-sharpened after my own field dressing. “Let’s get the guts out of this thing.”

“Oh no, Pinkerney. I called Fred Kratzke and told him I shot a tree-hundred pound buck and he called me a liar. Vee are going to take dis to him whole and veigh it vile he vatches.”

Good Lord!

So, Gerald got one antler and I took another and we grunted and sweated the buck to his pickup, 200 yards uphill.

Fred Kratzke lived on the east side of Otter Lake, rough country in Candor Township. He was German and his grandfather’s hand-carved sign still hung on the gable of the barn: Wo Felsen ist, ist Brot. Where there is rock, there is bread. Stony ground grew good wheat, in between the boulders.

Gerald judged his land better than Fred Kratzke’s. “Vhere dere is rock, dere is bread? Yah, but damn leetle cake.”

Fred Kratzke, his wife, daughters, sons and sundry kinnery were all gathered in the tractor shed, the deer were hanging and the drinking lamp was lit. Gerald and I struggled the buck to the platform scale, normally used to assay chicken feed. The buck, dead two hours, was stiffening quick. It was a trick getting the whole carcass on the scale, so not a hoof or a tine touched the floor. Weights slid, the beam rocked and the eager assemblage gathered round to note the results—298 pounds on the nose.

Fred Kratzke, his wife, daughters, sons and sundry kinnery were all gathered in the tractor shed, the deer were hanging and the drinking lamp was lit. Gerald and I struggled the buck to the platform scale, normally used to assay chicken feed. The buck, dead two hours, was stiffening quick. It was a trick getting the whole carcass on the scale, so not a hoof or a tine touched the floor. Weights slid, the beam rocked and the eager assemblage gathered round to note the results—298 pounds on the nose.

Crestfallen, Gerald and I hauled the deer back to the pickup to the guffaws of the Kratzke clan. Gerald reached inside his hunting coat, threw the buck’s testicles atop the carcass. Thump, splat. “Dese vould have made him tree-hundred pounds easy, but dere vere vas just too many vimmen hanging around.”

Invitation to hunt bear in Northwest Ontario, clean past Lake of the Woods. Shooting over clearcuts rather than deep in the jackpine snarl, I thought it wise to adjust the old Weaver accordingly. Alas, at 200 yards, the bullet holes were slightly oblong—the long 156-grainers were starting to yaw at maximum range for the short-barreled Mauser. I managed to kill a bear anyway and, when I recovered the slug, it had just started to mushroom, then went through the vitals sideways, dictating another change in armament.

I found it at a gunshow in Fargo, North Dakota, an arsenal refinished 1908 DWM Mauser in 7X57 made under contract for Brazil sometime before The Great War shut off export of Mauser rifles, both military and civilian. In original military configuration, it was far from woods ready, but Gerald Grahn introduced me to Arnold Landgren, a gunsmith and another Swede. Trouble was, Arnold Landgren was slowly going blind, and I wondered if he would ever get my Mauser done before the inevitable darkness overtook him. It took him seven years and it was the last rifle he ever made. When he was done, he stamped his name, a little unevenly, upon the barrel.

Arnold Landgren passed, Gerald Grahn passed, but the Mauser remains. With its gracefully swept bolt handle, full-length walnut stock and lustrous bluing, it is indeed a beauty. At 100 yards, it will put all the bullets into a inch all day long, remarkable for a full stock and a century-old bore. I took more deer with that rifle, a dozen black bears, wild boar, and I took it to Africa where I shot a puku in heavy cover and an impala at impossible range. It’s still on my gunrack, still my go-to rifle, my first choice, my only choice, the only big-game rifle I will ever need or want.

Make mine a Mauser, henceforth and forevermore.

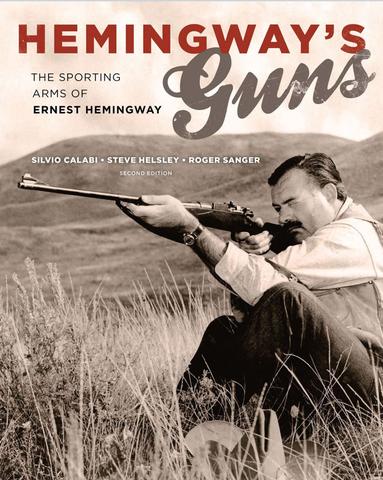

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now