Unlike many artists, Carl Rungius had been fully appreciated during his lifetime.

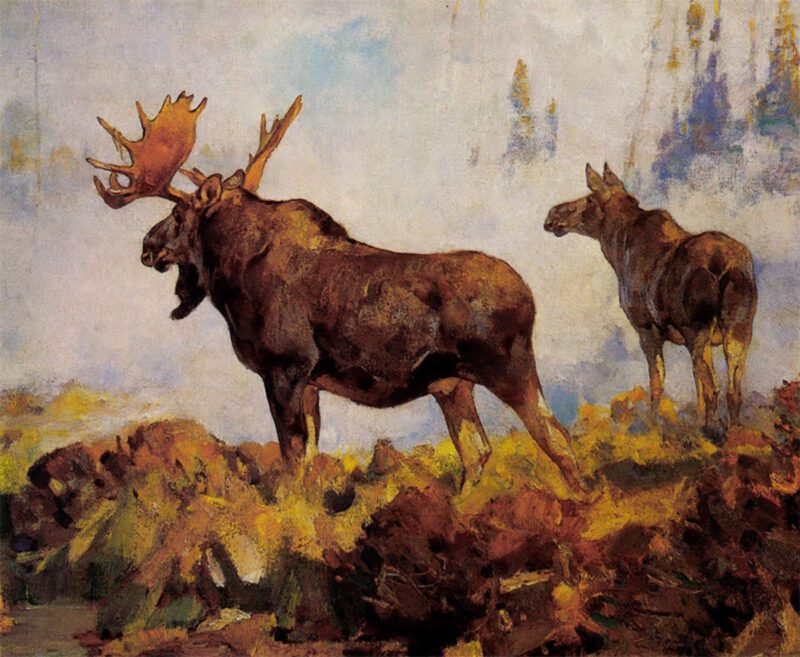

On a winter day in 1913, Carl Rungius was alone in his studio on West 42nd Street, at work on a painting of a bull moose. There was a knock on the door. The artist was not expecting company. He put down his brushes and answered the door, surprised to find Teddy Roosevelt standing there. Rungius knew the former president, but was not a personal friend. Rungius invited him in, and Roosevelt immediately walked over to the easel, curious to see what he was working on.

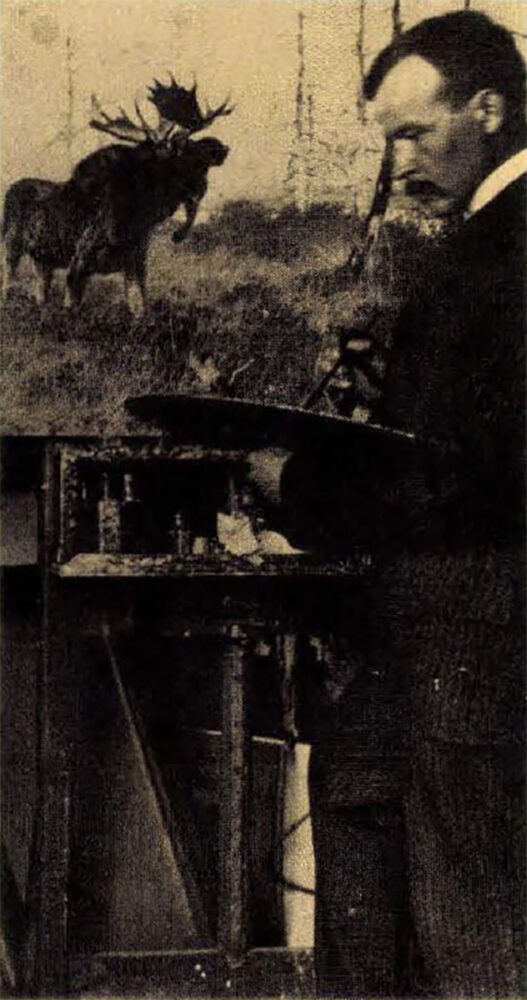

Carl Rungius in his upstairs studio at Fulda House on Kent Street in Brooklyn.

During his fall campaign to regain the presidency, Roosevelt had declared himself “as fit as a bull moose” when a reporter had questioned his health. The moniker stuck, and Roosevelt’s party became known as the “Bull Moose Party.” For his birthday in October, Roosevelt’s good friend August Heckscher had given him a Rungius painting of, most appropriately, a bull moose, with a proviso that if he didn’t like it, he could exchange it for another.

It was clear the Roosevelt was smitten with the canvas in progress. Rungius agreed to an exchange, and to bring the finished work by train to Sagamore Hill. On his way out the door, Roosevelt spotted Rungius’ only bronze of a moose (he did one other, a bighorn sheep, and each were small editions). Today, both moose painting and sculpture still reside in Roosevelt’s library at his home, now a museum in Oyster Bay, Long Island.

What had brought Roosevelt to Rungius’ studio that day was not just his appreciation of the artist’s talent for painting a subject which both men deeply admired. Nor was it the fact that Rungius captured the correct anatomy and appropriate habitat. What Roosevelt saw in this moose painting was a lone bull striding forward, head lowered to meet his challenger — an image charged with all the power and charisma for which the male of this species is famous. “Why, that’s the most spirited moose painting I’ve ever seen!” he exclaimed.

Just how Carl Rungius came to be the most admired portraitist of big game is a saga of opportunity, talent, determination, and luck. Ironically, some of the crucial events which launched Rungius’ long and productive career hinged on his favorite animal, the bull moose. If Rungius were to have chosen a talisman, it would most certainly have been a moose.

November Morning and other paintings in this article are reproduced courtesy of JKM Foundation in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

As a young boy growing up in Germany, Rungius dreamed of painting the furious battle of two bull moose during the rut. But moose had been extirpated throughout much of Europe by the mid-1800s. What few remained were on great private estates of the nobility, and thus inaccessible to a boy from a middle-class family.

Rungius’ father, a Lutheran minister, wanted his oldest son to have a proper career, the church and the military being the most desirable choices. The career of an artist was of “doubtful prospect.” So, in 1894, at age 25, Rungius apprenticed to a house painter to appease his father.

The following year, Rungius received an invitation from his uncle in New York to hunt moose in Maine. Dr. Clemens Fulda, a physician who had emigrated from Germany as a young man, was a keen hunter who had never pursued game as large as moose. He knew of his nephew’s enthusiasm for hunting, and realized that sporting opportunities were limited in Germany. With the invitation, he enclosed funds for Carl’s passage, making it hard for the elder Rungius to refuse. The first in a series of pivotal events had begun. Rungius sailed for the United States.

The September moose hunt was a disaster. The hired guides turned out to be fishermen, not hunters, but Rungius seemed pleased at least to shoot his first white-tailed deer. His uncle, disappointed, invited him to stay for the following year. Although he knew Carl was homesick for his brother and seven sisters, Dr. Fulda believed that his three cousins, Carl, Louise, and Harry, who were only slightly younger than Carl, would provide ample companionship. This arrangement appealed to Rungius, who set up his studio on the top floor of Dr. Fulda’s comfortable home in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn. They agreed to try for moose again in the fall.

The September moose hunt was a disaster. The hired guides turned out to be fishermen, not hunters, but Rungius seemed pleased at least to shoot his first white-tailed deer. His uncle, disappointed, invited him to stay for the following year. Although he knew Carl was homesick for his brother and seven sisters, Dr. Fulda believed that his three cousins, Carl, Louise, and Harry, who were only slightly younger than Carl, would provide ample companionship. This arrangement appealed to Rungius, who set up his studio on the top floor of Dr. Fulda’s comfortable home in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn. They agreed to try for moose again in the fall.

The decision to stay in New York proved to be the most crucial in Rungius’ life, for that winter he made two acquaintances that were to change the course of his life. Rungius met Ira Dodge, a guide from Wyoming, at the First Sportsmen’s Show held at Madison Square Garden. Dodge was there, dressed like Buffalo Bill Cody, representing the United States Cartridge Company. Rungius later described him in his biography by William Schaldach, Carl Rungius: Big Game Painter, as “the first buckskin man I had ever seen and a thoroughly Remingtonian figure. The upshot of this was that, early in the summer, I was on my way to Wyoming with little money and a little short of English.”

The second important character to affect Rungius’ career was William Temple Hornaday, first director of the recently founded New York Zoological Society in the Bronx. Here again, a moose figured in the event. Letting his artistic imagination supply what had not materialized in Maine, Rungius had painted a life-size moose head from a mount by a local taxidermist. Through a friend of his uncle, he was able to exhibit the portrait at a gallery on Fifth A venue. One wintry night in February 1895, Hornaday and his wife potted the portrait in the lighted window from across the street. “One look convinced us that it was something new and different,” said Hornaday. “Boldly and confidently painted, it was signed by a name both new and strange —C. Rungius.” Hornaday tracked down the artist and invited him to the zoo. Abundantly self-confident and eager to play impresario, Hornaday took Rungius under his wing.

Rungius with a bighorn ram shot in 1914.

Hornaday’s connections proved invaluable to the young artist. George Shields, editor of Recreation magazine, hired Rungius to do illustrations, and arranged free rail passage for what were to become annual trips to Dodge’s ranch in Cora, Wyoming. Another of Hornaday’s colleagues, George Grinnell, dynamic editor of Forest& Stream magazine, was a close friend of Roosevelt. Over dinner one night in 1888, Roosevelt and Grinnell founded the Boone & Crockett Club, an exclusive sportsmen’s fraternity dedicated to the preservation of America’s big game species. (Rungius was elected a club member in 1927.)

The opportunities presented by such a high-level entry into New York circles were too fortuitous for Rungius to deny. Even though he barely understood the language, he knew that living in America would enable him to do exactly what his heart desired — to become a painter of big game. In 1896, the 27-year-old artist returned to his family in Germany, and after a lengthy visit, packed his belongings and sailed back to the country that had opened doors never possible in his homeland.

Rungius’ early years of study were during the summer and fall at Dodge’s ranch. He combed the rugged Wind River Mountains hunting elk and pronghorn , quickly becoming proficient enough with pack horse and saddle to guide himself for weeks at a time. He paid Dodge a dollar a day for the outfit and, in addition, brought back meat for the ranch.

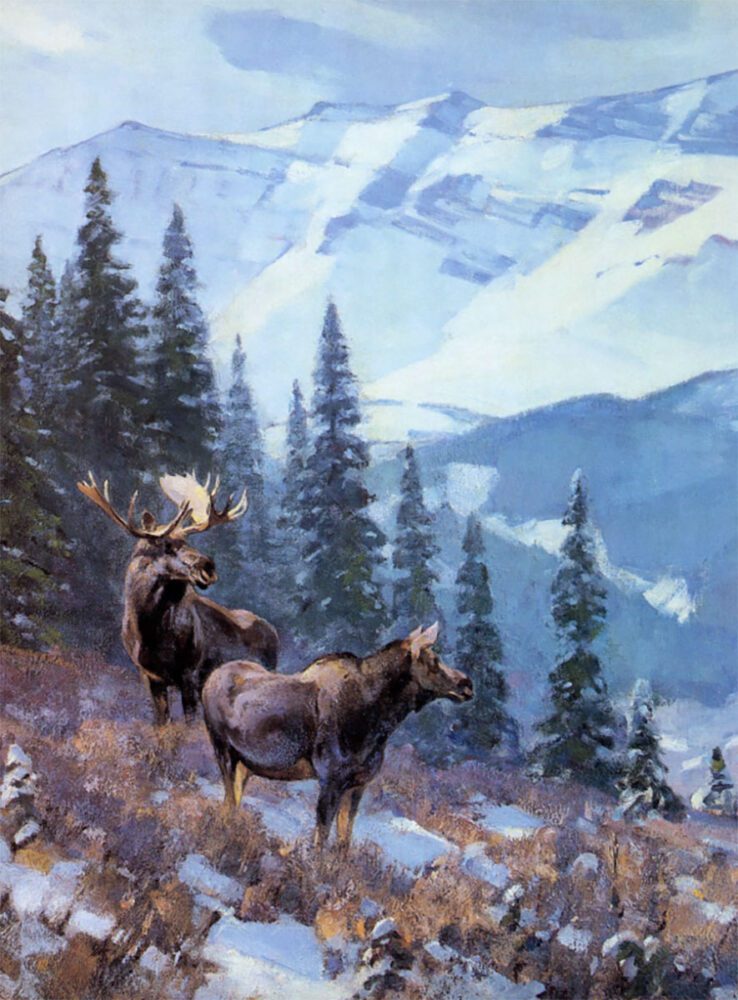

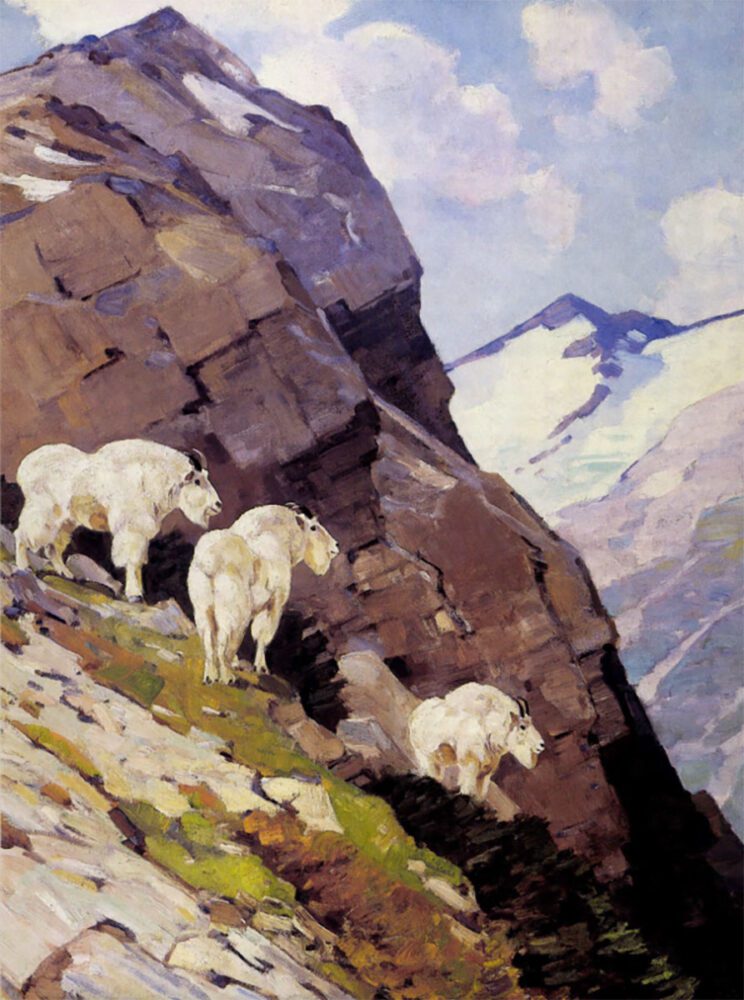

Coming to the Call, circa late 1920s.

In an interview years later, Rungius said: “I loved the solitude. I used to travel up into the hills about 25 miles from any habitation. And I’d stay there for four to five weeks, often until my work was finished or my provisions were exhausted. My pack consisted of bedding, clothing and implements — as well as my painting and gunning paraphernalia. Then I had flour, bacon, tea, dried fruit and a few other staples. At first I could only make flapjacks.

“The advantage of being alone is that one man can get much closer to his quarry than if he were accompanied by several other. I get more inside the life of my models when I go after them myself. But hunting in the West isn’t what it used to be. I’ve seen thousands of antelope in places where antelope are now almost unknown. And I’ve shot a moose in Wyoming eighty miles south of where they find moose now. My moose had the record at the Zoological Society for being shot furthest south.”

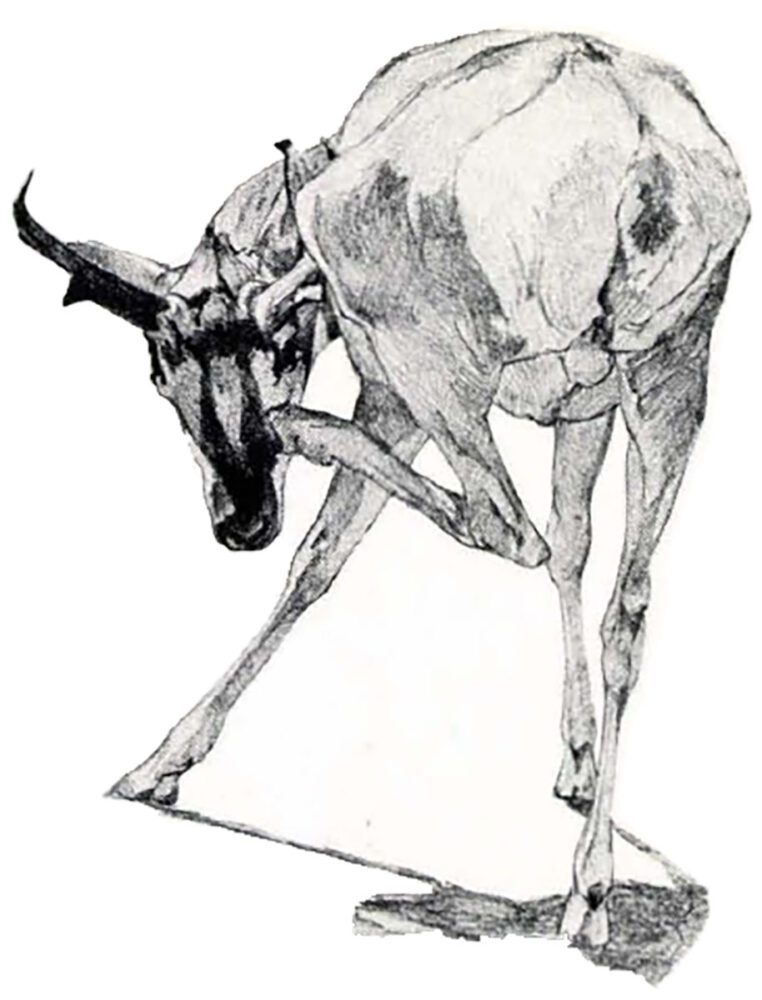

During those Wyoming years, Rungius established methods of field study that remained basically unchanged all his life. The animals he killed were strung up between tripod made of branches, and posed in a manner to indicate running, walking, or scratching, actions too quick to record by sketching from life. Rungius would then make detailed pencil drawings from different angles. Later he would work these poses into finished canvases back in New York.

Rungius considered himself largely self-taught, but his ability to draw was honed under the strict tutelage of a German professor at the Berlin Academy of Art. There, students learned to work from live models against the clock to develop rapid eye-hand coordination. Rungius’ ability to record quickly what he saw, fir t with pencil and later with brush, became the cornerstone of his stylistic development later in his career.

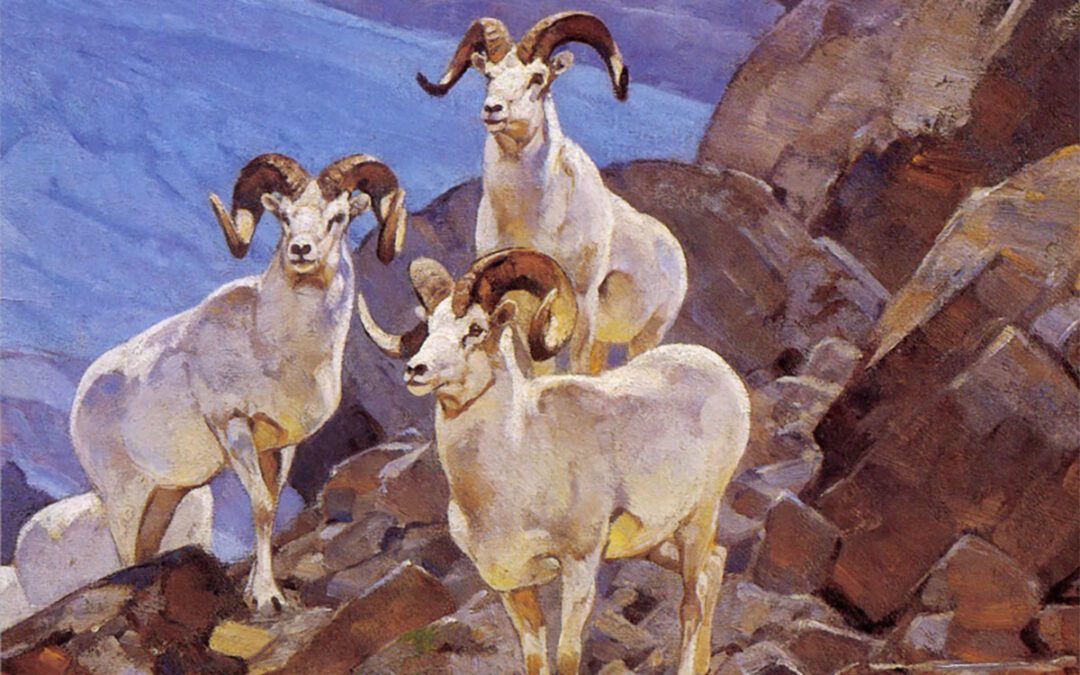

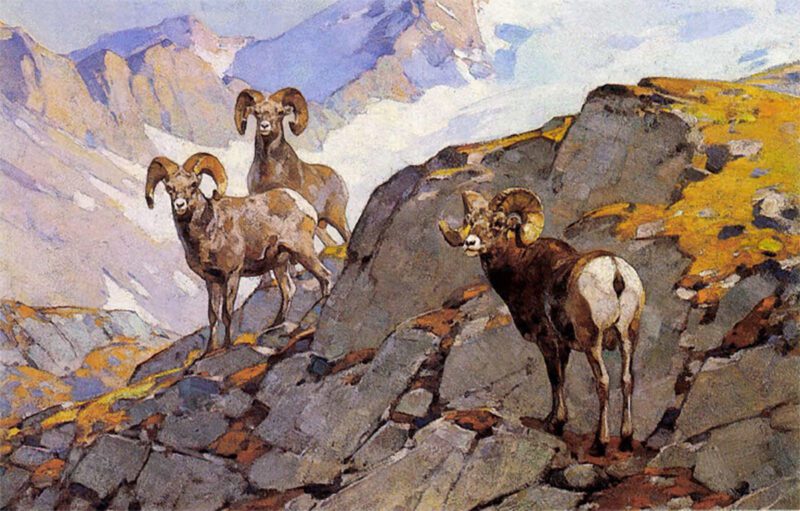

Mt. Athabasca, circa early 1950s, depicts a trio of bighorn rams.

Rungius once said, “The secret of all success is a willingness to work. I have always been a hard worker.” His innate German discipline and attention to detail reaped huge benefits during his early years in the field. Even when game was scarce, he made 9×12 oil studies of horse and cattle, trees and rocks, recording information on light, shadow, and color.

In his correspondence, Rungius rarely discussed art, but on a few occasions, talked about methods with friends and colleagues. Their recollections provide insight into his painting techniques. One was Canadian artist Clarence Tillenius, who had sought out Rungius for guidance and criticism. He was especially helpful on the subject of form.

“To gain strength,” Rungius advised, “see your forms in flat planes — think of an apple peeled — a sphere made up of flat planes. Think of every round or cylindrical object that way. Tree trunks, for instance, rocks, boulders — make them so a single brushstroke makes the plane. To emphasize the plane and keep it distinct, make a light patch within the edges of the darker plane.”

Coming to the Call, circa late 1920s.

His parting advice to Tillenius: “If something bothers you in a newly finished painting, leave it a few weeks and then look at it again. If it still bothers you, change it, or it will never give you any peace. That’s what art is about.”

In Wyoming, while the artist was gathering important material, Rungius the hunter was learning the behavior and habits of his subjects, and also to become more selective.” While I shot bulls (elk) during the first two years, they were not very good heads; the novice is too anxious to shoot when the occasion offers. But soon I learned the animals’ habits, knew where every bull with a good head stood, and where they went when the weather changed. From that time on I wouldn’t consider taking a head under 55 inches.”

Rungius not only lost his heart to the West, he also lost it to cousin Louise. They were married in 1907, just after Louise graduated from college with a teaching degree. Rungius, 37 at the time, was keenly aware of the financial risks of his career choice, and had waited 11 years to ask for her hand. As he once explained to a reporter, “When I returned from selling 15 pictures at an exhibition in Philadelphia, I proposed.”

Until 1904, Rungius’ field trips had been to Wyoming and New Brunswick. But that year, William Hornaday convinced his friend, railroad magnate Charles Sheldon, to take Rungius on an expedition to the Yukon. Sheldon wanted to collect specimens of Ovis dalli dalli, hopefully to determine if the animals were a race of Dall sheep or a new species. The trip proved arduous, but Rungius found new landscapes to inspire him and new subjects to paint, among them Dall sheep and caribou.

Field conditions in the Yukon were the worst he ever experienced: “This was in July and the mosquitoes were at their peak. Our backs were covered with them even on the highest mountain tops and you had to brush your gunsight to shoot — and what about painting? Making oil sketches was possible only with gauntlet gloves and mosquito veils, and the finished sketches looked like mince pie with the crust off, and had to be cleaned in camp with a forceps before they dried on. Pencil sketching was only possible between smudge fires and a good deal of choking, as I couldn’t see through the netting sufficiently to draw. Mosquito dope was useless, and we used it for our poor horses.”

Despite the hardships, Rungius found the terrain inspiring: “A sinking winter sun was painting the snow-covered summits and outcropping cliffs rose and gold until they were lost in purple haze in the distance, while the valleys, in shade, were a cold deep blue. “This new interest in landscape was soon reflected in his work. Instead of the somber tones of German Realism that characterized his early paintings, Rungius began using more color, notably warmer yellows, oranges, and bright yellow-greens.

Rungius was determined to achieve recognition as an artist, thereby attaining recognition for his subject matter in respected circles. To earn money in the early years, he did commercial illustration. But to succeed at what his heart desired, full-time easel painting, he had to establish his reputation as a painter first, and as an animal portraitist second. To achieve this, he turned to landscapes and western subjects which had more popular appeal.

Rungius was determined to achieve recognition as an artist, thereby attaining recognition for his subject matter in respected circles. To earn money in the early years, he did commercial illustration. But to succeed at what his heart desired, full-time easel painting, he had to establish his reputation as a painter first, and as an animal portraitist second. To achieve this, he turned to landscapes and western subjects which had more popular appeal.

He had set his sights on memberships in the proper organizations, and in 1906, began submitting paintings to the National Academy of Design. The next year, Rungius was elected to the Salmagundi Club, an important social meeting place for prominent artists and writers. In 1913, he was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design, the most prestigious organization of the time, and one that practically guaranteed financial success to artists who made the grade. He was 44.

In 1920, Rungius was elevated to the rank of full academician. From then on, he concentrated on gaining acceptance of his animal subjects since he could enter shows without passing a jury. Rungius won several important prizes, including the Academy’s highest award, the Carnegie Prize, in 1926 for his brilliantly colored landscape of Lake McArthur in British Columbia. In 1910, Rungius received a letter from Alberta guide Jimmy Simpson, who had seen a reproduction of a Dall sheep painting Rungius had done after his Yukon trip. Simpson knew sheep well and recognized a superior talent at work. He offered to supply and guide Rungius to bighorn terrain near Banff.

The two men had much in common. Both were small, wiry, self-made, and resilient, with a great love for the wilderness, and mutual respect for each other’s abilities. For his supplies and expertise, Simpson received a painting foreach expedition.

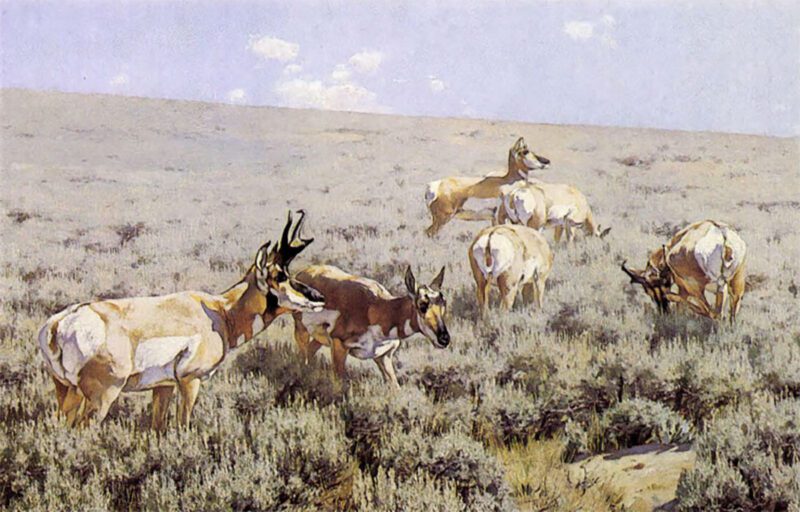

Spring on the Range, painted in 1900.

Rungius hunted and painted with comparative ease in the mountains he later adopted into his heart and painting. In 1922, with Simpson’s help, Carl and Louise built a summer home and studio, which he christened “The Paintbox.” From then on he alternated homes between Banff and New York — mid-April to mid-October in the mountains and the winter months in New York, where he painted most of his finished works.

Although Rungius had painted the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming since 1895, he found the atmosphere of the Canadian Rockies more inspiring:

“Wyoming is fairly arid in most places and lack of humidity — atmosphere’ to a painter — results in sharp edges, even at a distance, which gives objects a photographic appearance. But in Alberta, with its scenic grandeur and its remarkable wealth of big-game species, I felt that I had found at last the land which I had been seeking.”

As his eye and knowledge developed, his painting style began to change, natural with any artist. In Rungius’ case, his field studies in oils, done in an hour or two to record changing light and color, caused him to use rapid, coarse brushstrokes, and to make color judgments based on working wet paint into wet paint without letting the undercoat dry before overpainting. Like the Impressionists, Rungius discovered that color brilliance was enhanced by laying color components next to each other, letting the eye do the “mixing” at a distance from the canvas.

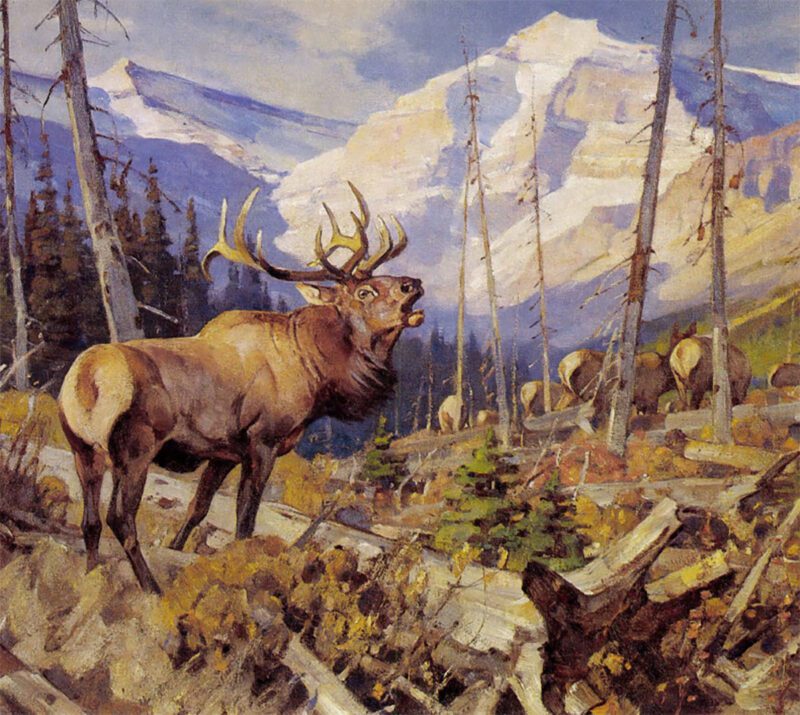

The Herd Bull, circa 1930s.

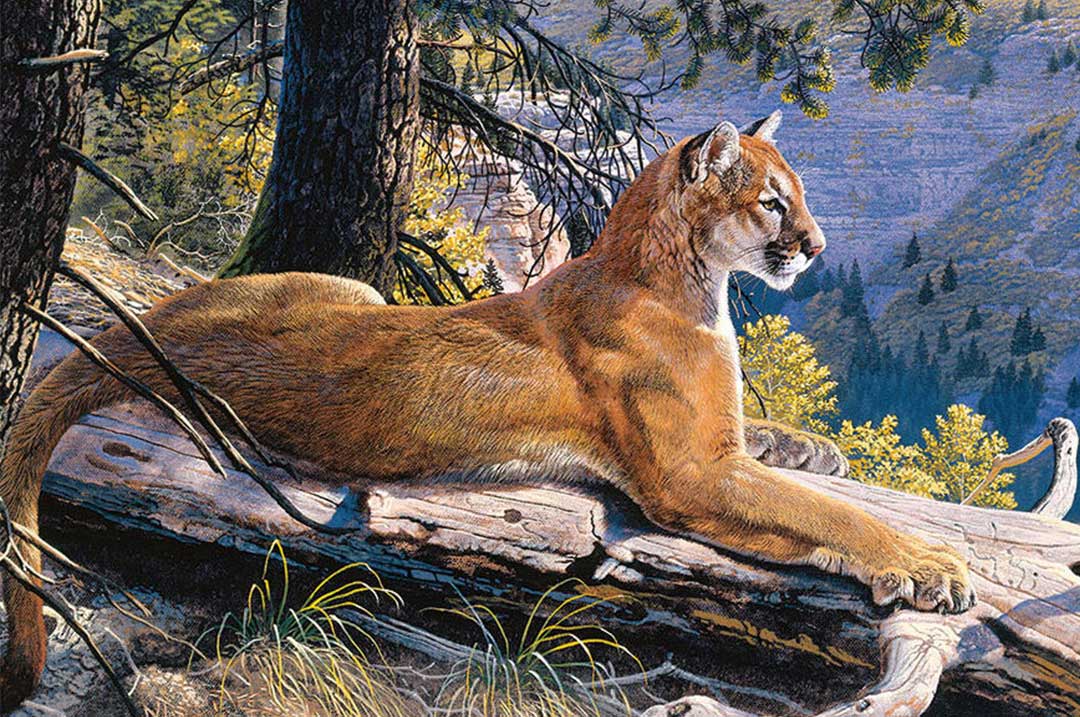

Rungius’ painting, from the 1920s until his death in 1959, evolved along Impressionistic lines, but he never strayed from being a realistic interpreter of his subject matter. His early work is more photographic and illustrational: He created drama and interest through story-telling action, such as deer fleeing a hunter and showing a panicked white in the eye to increase the impact of the image. This worked well for the outdoor magazines, but when it came to easel paintings, Rungius realized that such drama was difficult to live with over a long time. He was sensitive to the desires of his clients, mostly hunters who wished for a nostalgic portrait of the living animal, rather than a dramatic reminder of the actual hunt.

The New York Zoological Society’s collection of Rungius paintings, inspired by Hornaday who wanted a gallery of vanishing game, was commissioned over a period of roughly20 years. Between 1914 and 1934, Rungius painted about30canvases of different American mammals, some never duplicated like the wolf, wolverine, bobcat, seals, polar bear, and fox. Over this span, one can see his brushwork becoming looser and his palette becoming brighter.

The “modem” style almost brought his friendship with Hornaday to an end. Hornaday wrote to Rungius that his new style was a “horrible mistake, and it is of such a large size that in view of everything you have done before, it amounts to a tragedy.” Rungius diplomatically summed up his differences with Hornaday as “looking at art through different binoculars.” Indeed, the artist could sympathize because he himself deplored “modernism,” the evolution to non-objective subject matter. He remained a representational painter, grounded in drawing. “Modem artis a joke,” he told a reporter once, “just an excuse for not being a good draftsman.”

However impressionistically painted, a Rungius bull is always in his prime. He outlined this in a brief writing for the zoo’s Bulletin on bighorn sheep. “Whenever the artist intends to standardize a certain species, he must choose for the landscape that season of the year which will bring out the characteristic points of his subject. The pelage must be neither too long nor too short; and the animal must be in good condition.

“With some of our big game species, the growth of the winter hair produces changes so great that their external form seems to change completely, and go out of drawing. September is the month when the ram is at his best. Then he is an inspiring subject for the animal sculptor or painter. I might add that all our hoofed game looks its best during September and early in October.”

Rungius’ clientele was mainly wealthy hunters and sportsmen he met through his New York club affiliations, orthose who came through Banff, some even clients of his friend Jimmy Simpson. In those years, there were few art galleries in which to display paintings, so the clubs provided an important social milieu for promoting his work. Rungius was adept at mentioning, in casual conversation over cocktails, that he could turn a photo of a trophy into a lovely painting to hang in the den.

By the time he reached his early 50s, Rungius was clearly the best in the business. Because of his outstanding knowledge of animals and his ability with paint, he had very little competition. From the 1920s on, his larger canvases brought $1 ,500 to $3,500, and his gallery sold an average of two per month before the 1929 depression. He and Louise lived simply and invested wisely. When Rungius died in1959, he left an estate worth $675,000 in today’s economy.

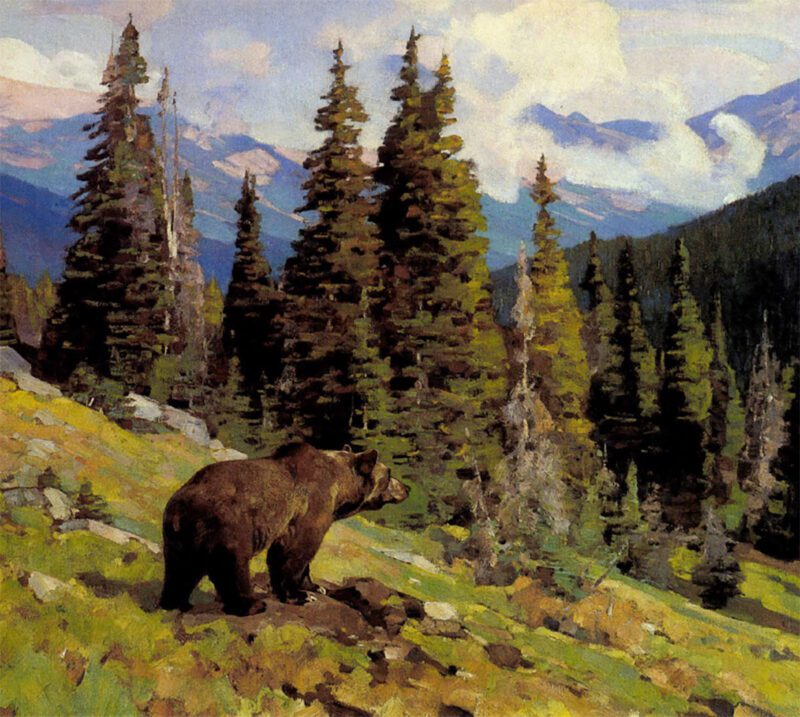

Alberta in the Late Summer, circa late 1940s, conveys the rugged grandeur of the Rockies.

And he was not above recycling a successful image or background. Rungius was merely following a long tradition. In his book Looking at Pictures, Lord Kenneth Clark said this about the great 16th-century painter EI Greco: “Like other painters whose ideas have come to them with unusual completeness and intensity, he was prepared to repeat individual figures or whole compositions as often as was required. This is characteristic of all magic art: Once the image is charged with its meaning it need not, or must not, be varied. The magic animal in Paleolithic paintings have identical outlines in northern France and southern Spain. No doubt EI Greco was satisfied that he gave his clients good magic. He had a large room containing small replicas in oil of all the pictures he had ever painted in his life. His customers could take their choice.”

Rungius gave his clients good magic too. Many who visited his studio, in Banff or New York, would provide photos of a favorite trophy or select one from heads that Rungius had hanging on his walls. Wisconsin hunter John Batten recalls visiting Rungius in his New York studio to commission a caribou painting. He had seen one of Rungius’ dry point etchings and liked the poses of his animals. It was decided that Rungius would use the image in reverse, and then Batten and his wife selected a combination of two backgrounds from hundreds of landscape studies.

After Louise’s death in 1940, Rungius lived alone, gradually falling back into the old habits he had formed while living on the trail, like sleeping in a sleeping bag rather than making a bed. Until his 80s, he attended the annual week-long ride of the Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies, which prepared him for his annual fall hunt. Although he was modest about his hunting exploits, he was proud of his ability as a marksman. Until he quit hunting in the 1950s, he only used rifles with open sights, a remarkable feat considering he had been nearly blind in his right eye since boyhood.

Rungius gave up hunting, but continued to paint, when a series of small strokes began to take their toll on his health. At age 84, in a letter to Smith in 1953, he complained: “Last summer was pretty dull, I did not feel too well, and my best friends in Banff had left town for good. Did not go hunting either, as my outfitter was busy early in the season, and hunting in Alberta has gone almost the same way as in Wyoming. And they built a new highway touching my hunting country. Well, I had my share!

“But in September, I walked three time up to Mount Edith to photograph rock; and while I was up there elk bugled below; it was grand and my climb did not t ire me in the least.

“My summer work consisted of goat, elk, and sheep pictures, I’m finishing them now together with some work from former years. That will keep me busy until I go West again. And so it goes, one pays for living too long, but I’m still enjoying it.”

He died of a stroke at his easel in October 1959, at the age of 90. His ashes were scattered on the slopes of Tunnel Mountain overlooking the spectacular Bow Valley and the town of Banff. He had been lucky. Unlike many artists, he had been fully appreciated during his lifetime. In 1931, at age 62, Rungius had been honored by the Camp Fire Club, receiving the tenth Medal of Honor in the club’s history, thus joining the ranks of its other illustrious recipients: William Hornaday, Gifford Pinchot, Teddy Roosevelt, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Dan Beard. The citation read: “For his outstanding accomplishments in the interpretation of the spirit of the wilderness and as a painter of wildlife.”

He died of a stroke at his easel in October 1959, at the age of 90. His ashes were scattered on the slopes of Tunnel Mountain overlooking the spectacular Bow Valley and the town of Banff. He had been lucky. Unlike many artists, he had been fully appreciated during his lifetime. In 1931, at age 62, Rungius had been honored by the Camp Fire Club, receiving the tenth Medal of Honor in the club’s history, thus joining the ranks of its other illustrious recipients: William Hornaday, Gifford Pinchot, Teddy Roosevelt, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Dan Beard. The citation read: “For his outstanding accomplishments in the interpretation of the spirit of the wilderness and as a painter of wildlife.”

This is his legacy. More than mere portraits of big game posed in magnificent surroundings, his paintings are romantic visions of an elemental world where life is survival, driven by the seasons, food supply, procreation, and luck. Rungius conjured up his most majestic imagery to give us the spirit of wilderness — imagery inspired by the breathtaking vistas of his beloved Rockies, and the animals he had come to know intimately in 65 years of life on their trail. These images have the power to speak to succeeding generations. And that is the magic of art.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1986 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

Inspired by the vanishing subgenre of agricultural memo books, ornate pocket ledgers, and the simple, unassuming beauty of a well-crafted grocery list, Draplin Design Co. brings you “Field Notes” in hopes of offering “An honest memo book worth fillin’ up with good information. Buy Now

Inspired by the vanishing subgenre of agricultural memo books, ornate pocket ledgers, and the simple, unassuming beauty of a well-crafted grocery list, Draplin Design Co. brings you “Field Notes” in hopes of offering “An honest memo book worth fillin’ up with good information. Buy Now