Angler, hunter and above all artist, Lynn Bogue Hunt was America’s most popular and prolific outdoor illustrator of the mid-20th century.

Note: This article is an excerpt from Tom Davis’ Lynn Bogue Hunt: Angler, Hunter, Artist.

Flushed by his success at Sports Afield and clearly feeling confident and battle-hardened after three years in the Free Press trenches, in 1902 Hunt followed his ambitions to New York City, then, as now, the center of the publishing and advertising worlds. Meaning, the worlds in which his clients, actual and potential, circulated. He found a place to live on the Upper West Side and, looking to beef up his repertoire and add a few arrows to his quiver, enrolled in what was called “antique art” classes at the famed Art Students League. When the last of these classes ended in January 1903, so, too, did Hunt’s formal training as an artist.

He had plenty left to learn—he was only 24, remember—but he had at least a couple of pretty powerful motivators. One, in that hyper-competitive, pressure-cooker environment, was simply to keep his head above water and survive. The other was to become well-enough established to marry Jessie, bring her back to New York and make a home and a life with her.

Hunt’s pen-and-ink drawing of a whitetail buck was published on the title page of Firelight, Burton Spiller’s 1937 classic.

He succeeded on both counts. According to Shelly, Hunt cleared $3,500 his first full year in New York, a tidy sum roughly equivalent to $70,000 in today’s dollars. And on June 11, 1903, he married Jessie Bryan. The ceremony took place on Grassy Island; Hunt’s mother attended, his father was conspicuous by his absence. For their honeymoon, the newlyweds took a leisurely steamship voyage through the Great Lakes and down the Hudson River back to New York, disembarking at Rochester for a few days to visit Hunt’s boyhood home in Honeoye Falls. On July 2, the couple moved into their first home together on Staten Island.

More than 40 years later, in a chapter entitled “Long Island Pond Shooting” for the book Duck Shooting Along the Atlantic Tidewater (compiled and edited by Eugene V. Connett of Derrydale Press fame), Hunt—writing again in the third person—reflected somewhat wistfully on that idyllic time.

“When this young man took the bit in his teeth, deserted a living job on a Detroit newspaper for that Mecca of all ambitious artists, New York, he settled himself there, began peddling his wares and looking over the shooting possibilities. He picked Staten Island as a place to live, where rents were cheap and he could enjoy the never-ending glory of the ferry ride to the city. In spare time he hunted the marshy shores of the island and discovered, to his amazement, black ducks galore. No mallards, no pintails, no teal—just black ducks, except for a few scoters and old squaws offshore. And all this in a borough of the great city only a few miles away…”

Hunt had an exceptional talent for arranging a flock of ducks in a realistic yet eye-catching composition. Scaup on the Outer Beach is based on a hunt at Sandy Island in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey. The oil on canvas appeared in Van Campen Heilner’s A Book on Duck Shooting.

Shelly refers to the period in Hunt’s career from 1903 to the mid-1920s as “The Journeyman Years,” and by and large this seems apt. Hunt was paying his dues, building his portfolio, making connections, establishing his reputation—all the things necessary for an artist competing against other artists for assignments, commissions, work. It’s all about convincing an art director, or an editor or an advertising manager that you can attract more readers, reach more customers and simply do a better job delivering the goods than the other guy can. Hunt learned early on that he had to earn whatever he got, that nothing would come easily.

Hunt enjoyed hunting pheasants and other upland birds, but he wasn’t much for roughing it in the great outdoors. After the hunt he preferred to return to a good meal, a drink with ice in it and a comfortable bed.

So he put his shoulder to the wheel and kept pushing. At first he did a lot of work for Sports Afield, including a number of covers that were “repurposed” (i.e., re-used) for multiple issues; he also wrote and illustrated several articles for Outing, a popular magazine of the era that specialized in long, somewhat rambling first-person accounts of hunting, fishing, and “outdoor adventure.”

The first of his record 106 covers for Field & Stream appeared in August, 1904, the second in December 1908—but it wasn’t until May 1924 that he painted another F&S cover. The reasons for the long hiatus are anybody’s guess—maybe he spilled a drink on the magazine’s art director at a cocktail party—but the most likely explanation is that, to a degree unrivaled before or since, there was simply a hell of a lot of top-drawer illustration talent to choose from.

This was particularly the case with the group of painters, all students of the legendary late 19th/early 20th century illustrator Howard Pyle, who came to be known as the “Brandywine Artists.” Led by the incredible N.C. Wyeth (father of Andrew and grandfather of Jamie) and noted for their stirring brand of heroic realism, their ranks included the likes of Philip R. Goodwin (designer of the iconic Winchester horse-and-rider logo), Frank Schoonover, Howard E. Smith, Frank Stick, and Oliver Kemp. The Brandywine Artists dominated American outdoor illustration in the early 20th century—and to a man they were born within a few years of Lynn Bogue Hunt.

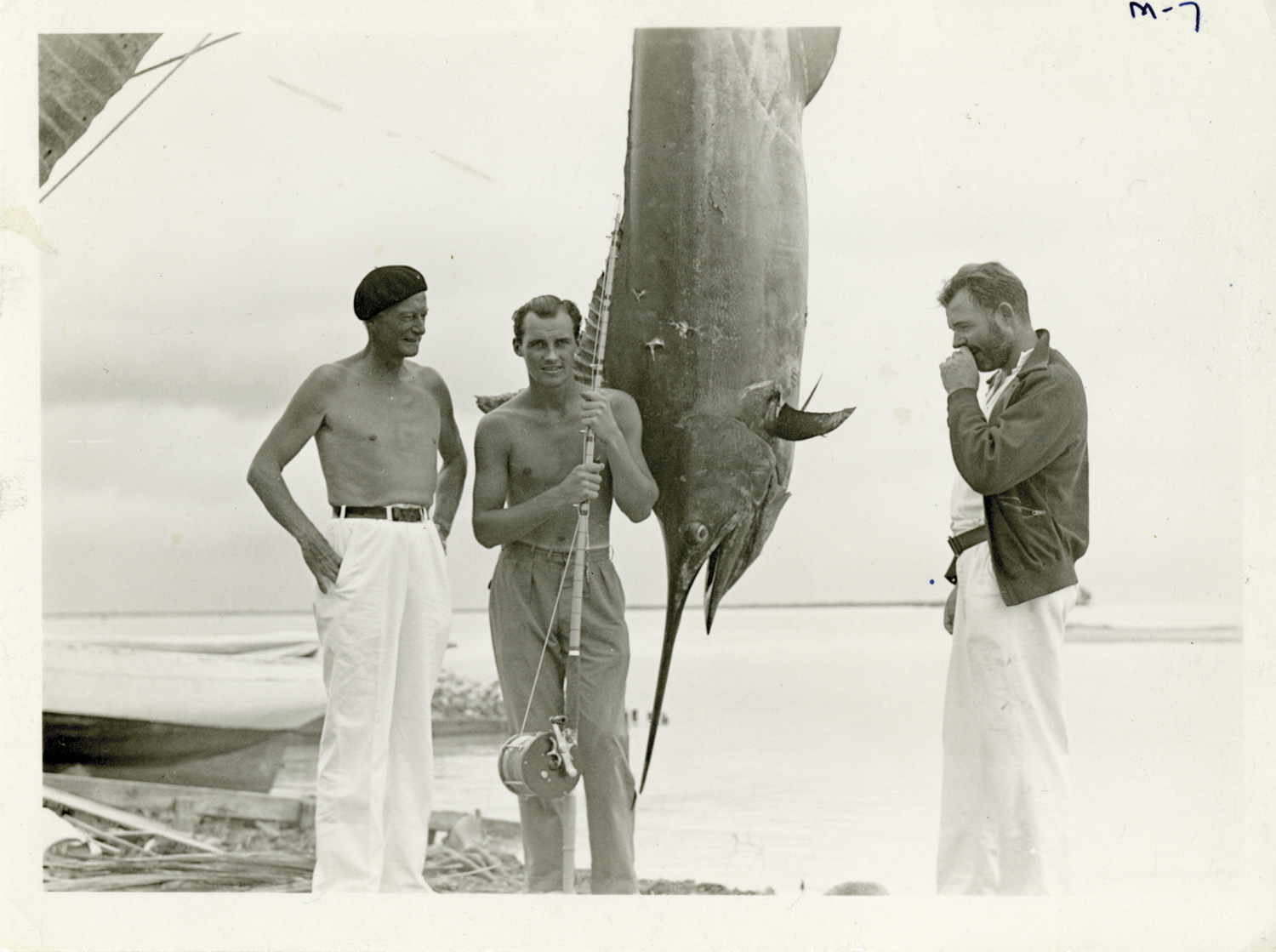

Lynn Bogue Hunt (wearing cap) poses with Ernest Hemingway (far right) and wealthy sportsman Tommy Shevlin with the new world-record blue marlin. Shevlin caught the 636-pounder off Bimini Island in the Bahamas in 1936.

The legendary A.B. Frost, “The American Sportsman’s Artist,” remained active during the early part of Hunt’s career as well. This was also the heyday of the great gundog artists Edmund Osthaus and Gustav Muss-Arnolt. The point being that the competition Hunt faced for illustration work was ferocious. He couldn’t afford to relax for a second, to take a single job for granted. Nothing but his best was going to cut it, and if his best wasn’t good enough, it meant he had to bear down and get better. He wasn’t just running with the big dogs; he was swimming with the sharks.

This article is excerpted from Tom Davis’ Lynn Bogue Hunt: Angler, Hunter, Artist.

This article is excerpted from Tom Davis’ Lynn Bogue Hunt: Angler, Hunter, Artist.

Here, for the first time, is the Vartanian Collection in its entirety, some 150 iconic images that will thrill Hunt fans and be a revelation to those less familiar with this legendary artist. With text by noted writer and sporting art authority Tom Davis, this spectacular book promises to do what the art of Lynn Bogue Hunt has always done: Trigger the machinery of dreams.

$60 $20 Buy Now and Save $40!