All that day the old man’s thoughts were on Malachi, the grizzly and himself. He knew what he must do, but dreaded it.

Jasper Pratt came awake, suddenly pulled by the instincts of his breed as he heard the far-off cries of a wolf pack running down an animal, perhaps a doe, he thought. Looking around, he growled, “And just what would you be looking at?”

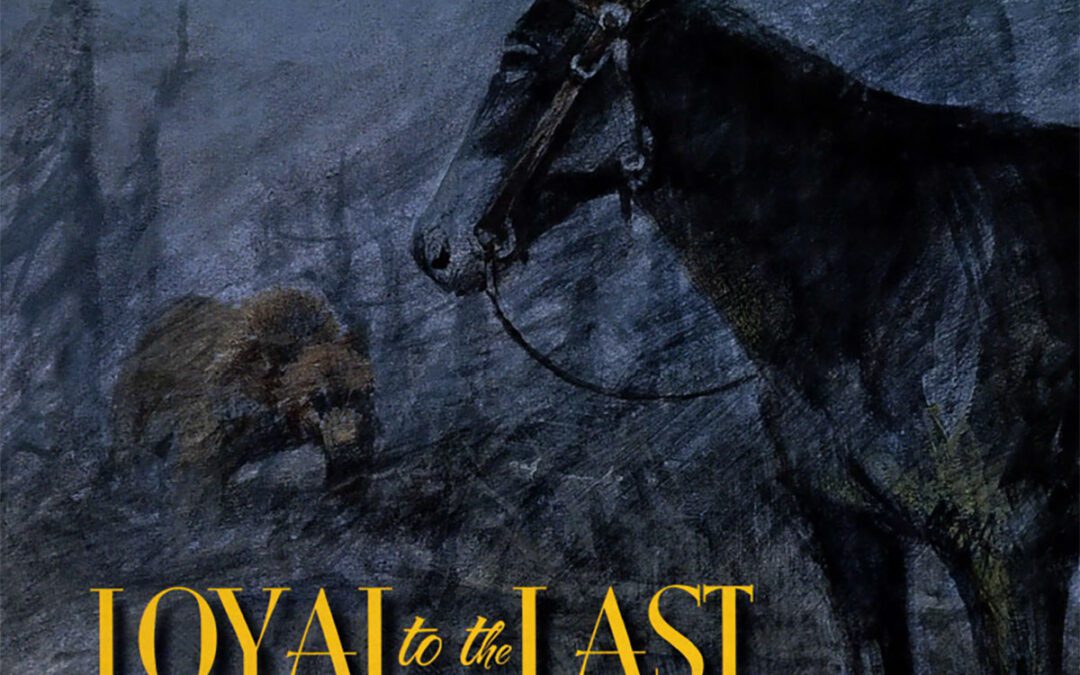

Malachi flattened his good ear and stared contemptuously at the old man who stumbled out of his bedroll in faded red underwear to scratch here and there, spit the dregs of his throat into a spent fire, empty his bladder and run a hand through tangled strands of loose white hair. His hat went on before his pants, boots, wool shirt and winter coat, his eyes constantly scanning the tiny clearing they’d camped in and beyond the whole time.

“Won’t be long before we wake to snow,” he mused.

Pratt set to digging out the buried, warm coals with a stick and then fanning them with his hat into smoke and flame to make coffee and biscuits. “Mule,” he said, “it’s a burdensome task I have of carrying you along. Can’t lightly say why I didn’t blow your brains out that floppy ear years ago.”

The old man turned away and coughed, the metallic blood taste in his mouth, and feeling once more the hollowness and chest pain he did not like to dwell on, but that hung at the back of his mind just the same.

Malachi had an excellent set of upper and lower teeth that, at times, he snapped shut to make his point, and used them now to gently bite the old man on his left side low down near his hip after moving close so he could take his share of tasty biscuits when they cooled — a morning ritual between them.

“Damn you, Malachi, cut that out,” said Pratt loudly while swatting the mule with a left hand, which had about the same effect as hitting a tree trump. “You’ll get your share, and you know it.”

The 17-hand black Spanish jack paid no heed.

When Pratt was seated in the Mexican saddle after breaking camp, Malachi snorted to clear his nasal passages, stuck his muzzle into the morning breeze, took a deep sample of up-wind weather, shifted his frame to adjust the load on his back, bugled once rumbled off, heading south.

The sun was at its peak when Malachi stopped at the hitchpole in front of a line of buildings on the main street of the small town of Jackson, Wyoming. Pratt eased down, draped the reins across the saddle and spoke, “Be here when I come out.”

The sign hanging above the door read “Dr Brooks.” Pratt entered.

“Morning, sir. How can I help you?”

Pratt eyed the tall, slim young man dressed in a white shirt and linen pants.

“Came a long way to see you. There’s a sawbones in Missoula that kills more folks than he cures. Word up north is that you’re good at doctoring. Is that true?”

“I try to help people the best way I was taught,” the doctor said, smiling at the remark.

Pratt nodded. “Can’t seem to get a good breath of air anymore … my chest hurts and I’m coughing up blood.”

Dr. Brooks had Pratt remove his shut, undo the buttons of his long-johns to his belly and take several deep breaths as one end of a contraption was placed against his chest with the connected hose plugged into the doctor’s ears. The deep breathing started the coughing and soon blood came.

“May I look at that bloody handkerchief?”

Pratt handed him the rag, crusted and stained with dried blood, and now fresh.

The doctor sighed, “Sir, you have lung fever and there’s no cure. I can give you cough syrup that will last a few weeks, but that’s about all I can do. If you were to ride south into Arizona or Old Mexico territory where the climate is dry and hot, you might live, Some have done that with surprising results, but there’s no guarantee.”

“Too far,” Pratt said. “Whiskey’s about as good as cough syrup — tastes the same and works wonders for the body and mind of a salty old man.”

The doctor smiled, but no humor reached his eyes, “Sir, you’re going to die, and from the color of that blood, soon. Do you have family?”

Pratt grunted, showing no outward emotion at the bluntness of the declaration, “Had a Cheyenne woman live with me for four years when I was younger. Lord, was shea looker. Made the mistake of taking her back to visit her people and she quit me cold, A good woman, she was.”

“Do you live around here?” the doctor asked.

“Nope. I got a cabin up north in Montana Territory Reckon I’ll cash in there if I don’t die on the trail somewhere getting there.” Goodbyes were said, the doctor wishing Pratt luck as the old man turned the mule north again.

Pratt had raised Malachi from birth eight years before and loved the mule more than his own life. He needed Malachi now more than ever, his hearing and eyesight having dimmed with time and age. With aching joints and bad knees, he could no longer walk up and down mountains on foot, and now lung fever.

In the rose and canted light of Northern Cheyenne and Sioux Indian country, Pratt sat the mule among rocks and looked around as shadows ran over the land. He could see the trace of a trail heading north through timber on the east side of the Snake River where painted ponies and riders of nations once rode south and east with chalked faces, long hair pleated and armed for war. The same bail was used by wintertime trappers to get to the Wyoming hole ringed by mountains with geysers and hot springs. When the wind was light, he thought he could hear them — horses’ hooves, the rattle of lances and travois poles on dirt and sand.

Darkness had arrived by the time Pratt watered Malachi at a stone stock tank amidst the rubble of a squatter’s shack where he would camp for the evening. The air was clear and cold with sparks from the fire rising hot and flaring away among the stars.

All the next day he rode with October sun and wind blowing out of the west, coppering his face. Turning northeast along what he knew was a not-too-long-ago war trail to the crest of a high ridge, he sat the mule hip-shot, looking, listening and hoping for the sounds of warriors riding north out of Arizona and Old Mexico once again. At 69, Jasper Pratt was still a dreamer of the past he knew so well that fall of 1888.

Another day found the old man fishing the Gallatin River far south of the tiny town of Bozeman, Montana. Pratt had shaved down, curved and sharpened the tips of elk horns, and bored holes in the larger ends to use as fishhooks. They ranged in size from a half-inch to an inch. Baiting one hook with parts of a grasshopper and tying it to a long, thin strand of deer hide, he soon had four brown trout for his supper. He preferred the needle-fine, curved horn to fishhooks.

Malachi sampled the smoky wind around the tiny fire, snorted in disgust at the smell and sauntered off to crop meadow grass that night while the old man feasted on fresh-caught trout.

Nine days later, mule and rider jumped a spiked buck from a stand of fir trees just north of Bozeman in the Gallatin Mountains, and Pratt shot it. That night, as he took a stick from the fire to poke coals and push unburned limbs close to the flame, the mule came close, his head riveted toward a dark form across the meadow to the north, his legs stiff, his muscles bunched and ready.

Pratt rose silently to stand by Malachi, his right hand cradling the cocked .44-40 Winchester carbine, the palm of his left hand on the mule’s shoulder, feeling muscles hard as rocks move and twitch. “Easy mule.”

Pratt thought about the deer kill; long strips of meat that hung near fire heat and smoke to dry. He’d carried the guts and hide far from camp, leaving them for scavengers. Was it a bear, cougar, wolves or an outlaw looking to upgrade his mount and gear? Pratt immediately ruled out a wolf pack. He had not heard them howl for three days, and Malachi was more than a match for them.

“What’s out there?” Even as he asked the question aloud, he knew. Bear, cougar or man.

After a half-hour of vigilant staring and waiting, Malachi dropped his head and moved off to graze or nap, and Pratt laydown, but did not sleep. Grizzly bears were plentiful in the country he was in and mighty dangerous. He would need two more days to cure the meat before turning northwest toward home in the Great Bear Wilderness.

Home was a chinked log, three-room cabin that sat 40 miles east of Bigfork, with seasoned, cut wood for winter fuel, a bed, table, two chairs and provisions. Would whatever was out there get tired and move on, or was it stalking him?

He did not know.

Pratt did know that outlaws on the dodge rode far wide of trails and towns. But they needed grub and a fresh horse from time to time, and Malachi was superior to any horse he’d ever owned or rode.

By midday on the morrow, a line of crouching, rumpled clouds, interlaced with veins of lightning, drifted toward him from the northwest. “Mule, we’re in for some hard weather.” Pratt was speaking to himself as much as to the mule as he gathered branches and pine bows to make a shelter from the coming rain and perhaps snow. Pratt also laid a supply of firewood up close. He would need that.

For two days, he kept a fire going as he dried deer meat and waited out rain and then snow. In those two days, Malachi moved to the fire several times to stand guard over the old man as something in the timber riveted his attention, causing him to stamp a massive front hoof in tile dirt and pine needles.

Pratt thought about going out to confront whatever was there, but his poor eyesight and hearing were his enemies now. And in rain, snow and dim light, he was nearly blind to spot something out of place in the trees and brush. When the storm passed, two feet of snow covered the ground.

With a bright sun and clear day, Malachi paid no heed to snow-depths as he moved north, instinctively knowing they were going home. In late afternoon, of their first day of travel, after forting up to wait out the storm and dry meat, Malachi turned about suddenly to face the timber they’d just passed.

Pratt swore. We’re being stalked by a bear, most likely a griz. He felt it in his bones, and shivered. An outlaw would have come in and tested him by now. Without a rider, Malachi could defend himself against a black bear, but not a grizzly. Pratt had seen the mule kick black bears, mountain lions and wolves, breaking bones and sending them away howling in pain. Was the griz after the mule or him? Could it smell the sickness inside him? Was it a man-eater?

Dismounting, Pratt edged toward the timber, the carbine’s barrel chest high, the tarnished walnut stock tucked into his right side, his left hand cradling the barrel, his finger on the trigger. He shuffled forward slowly and silently, his watery eyes scanning every bush and tree, looking for movement, something out of place, the wrong color or shape, his ears tuned to every sound, all the time knowing he was a target, that the bear could charge him before he saw it and reacted. He might get one shot off, but would it be enough?

At the edge of the trees he stopped and waited, every nerve in his body tense, his breathing ragged, his muscles cramped. Behind him, Malachi bugled once and then turned to crop grass once again. The old man swore. The bear would choose the time and place, not me or the mule, he guessed.

At the edge of the trees he stopped and waited, every nerve in his body tense, his breathing ragged, his muscles cramped. Behind him, Malachi bugled once and then turned to crop grass once again. The old man swore. The bear would choose the time and place, not me or the mule, he guessed.

In morning light, Pratt backtracked to a stream to look for horse or bear tracks. What he saw sent shivers up and down his spine. Grizzly prints as big as tin plates pointed north where he was headed. He thought he could smell it. How close? “Tracking us on the left side, mule. You’ve been right all along.”

All that day the old man’s thoughts were on Malachi, the grizzly and himself. He knew what he must do, but dreaded it. Then, that night, by a fire, Pratt coughed so hard that blood began running from his mouth in a steady stream. He tasted the metal bite of it and gagged.

Minutes passed before the bleeding stopped. The old man sagged back against a log, what little energy he had was gone. “Damn you, bear, now’s the time,” Pratt spoke softly, afraid he’d start coughing and bleeding again.

Weak now, Pratt stood on trembling legs and patted the mule he had loved for a long time. Malachi had eaten a dozen biscuits that morning and was as content as if he had good sense, which he did.

“Mule, it’s been the best part of my life knowing and having you for company. Now it’s time we part. That grizzly’s coming … you can’t whip him, and I don’t want you to die trying. Now go on.”

He removed he bridle and bit, and lifting his wide-brimmed, beat-up cowboy hat, he swatted the mule’s backside. “Go, damn you. And quit looking at me like that.”

Tears ran down Pratt’s cheeks as the 17-hand black Spanish Jack moving off a-ways, then stopped to stare at him for a spell. The mule bugled once, then turned and disappeared into the timber, heading north.

“Damn mule’s too ignorant to know I ain’t going to make the cabin,” he muttered as he collapsed to the ground and wept. When no more tears came, he did not want to move. His lungs ached. Blood coated his lips, its metal taste gagging him. His strength was gone. He did not want food or coffee, and was too weak to fix any. With a trembling left hand, he reached for the Winchester rifle, levered a shell into the chamber and waited.

Had the old man guessed wrong? Had the grizzly really been stalking him and the mule? Perhaps for a while and then moved on, looking for something else. Had it made a kill, its belly full, content? Had he sent the mule away for nothing?

Pratt waited but the bear did not come.

Late-night darkness and cold woke the old man. Too weak to move, make a fire, drink or eat jerky, he laid on bare ground, his body getting colder and stiffer by the minute. Above him, blurry stars littered the dark sky.

Then a giant, dark shadow moved close to block his view of the heavens. Malachi stomped a massive left hoof near the old man’s right shoulder, his nostrils brushing Pratt’s shirt to let the old man know he was there, Pratt guessed. And then he bugled once.

“Damn, Malachi, if you ain’t something.” After that, with tears running down his cheeks, Jasper Pratt, mountain man, tracker, trapper, Indian fighter and cowboy, slipped away silently and slowly, his mind at peace knowing Malachi would guard him until he passed on.

The two cowmen that were pushing cattle toward winter range spotted and chased the mule for an hour until darkness, then the next morning trailed him to the cold fire where they found a saddle, bridle, gear, bedding and the body of the old man. Pete Steadman, trail boss and ranch foreman, wanted the giant mule.

Both men had experienced much over their lives, and they just sat their saddles, silently taking in the scene before them. The 17-hand black Spanish jack, with deep scratches and flesh torn off his sides and left hip, eyed them contemptuously, then went back to cropping grass close by the old timer’s body.

Earl Gardner looked at the big man beside him and in a quivering voice said, “I ain’t never seen nothing like that. Have you?”

“I reckon that damn mule led us to the old man,” Pete Steadman observed. “He wanted us to follow him, and sometime during the night fought off a grizzly to protect the old man.” Earl quickly removed his hat before Steadman had to tell him, seeing how moved the ranch manager was by the scene. “Back in Tennessee when I was a young’n, an old gent passed on that lived a few miles from us,” Earl said. “After my pa and others buried him, his coon dog lay down by the grave and wouldn’t be coaxed or drug off. Died there. I never thought a mule would do that.”

Steadman eyed the cowpuncher beside him. “I don’t think the mule plans on dying. I think he just led us to the old man and protected him until we got here. Earl, ride back and point the cattle in this direction, and send Cookie and the chuckwagon on ahead. Tell him to come a’ runnin’. We need to doctor that mule.”

“What about the old man?”

“We’ll bury the old gentleman proper. Reckon he deserves that. His kind came before us to explore, carve the trails, fight Indians, trap and tame the land. He deserves all we can do for him … we won’t ever see his kind again.”

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson.