A tangled tale from the Carolina Lowcountry where writing runs deep in the blood.

Half-moon of July, a low tide at noon, glaring blight sun and nary a breeze to ruffle the waters of Port Royal Sound. Piney islands shimmer in distant heat waves, surf grumbles far offshore while the whole world waits for the tide change, for God to catch His breath.

The slightest splash of an oar upon the water, then another. A 20-foot skiff gliding along, cypress, fastened with copper, she’s beautiful, deep, long and narrow, rigged for sail but the sails are furled. Six good men at the oars. The oars are hand-carved from oak and the locks are oak pegs driven tight into oak gunnels. The oars are muffled with rags and gunny sacks. There is no sound except the whisper of the occasional oar-wash and the soft grunt of an oarsman.

A man stands upon the stern seat, the tiller in his hand. He wears a broad-brimmed hat and he shades his eyes with his right hand. He points with his left toward a riffle on the sea, swings the tiller toward it. He nods at an oarsman who quietly pads barefoot to retrieve a harpoon. One oar-stroke, two, the harpooner winds up, the missile flies true, and the water erupts in wild, bloody froth. A line rattles after the harpoon and everybody stands clear, ’cause a loop around leg or arm is a snatch to certain death.

Five seconds, ten, the harpooner gingerly pulls a loop from the bottom of the diminishing coil and makes a deft turn around the bow cleat. The line twangs, the cleat smokes and stinks, and the boat takes off with a sudden lurch, almost catapulting the helmsman over the stern. Faster, faster, the skiff on a plane now, throwing a wake of white water. The oarsmen lay their oars in the bilge, whoop, holler and hold on. One man loses his hat to the wind but doesn’t seem to mind.

It’s 1842 and William Elliott has just harpooned another Devil Fish.

Devil Fish, we call them mantas these days. Manta birostris, 30 feet across, 3,000 pounds. Not much went to waste. Meat and leather, oil for shoe and harness, scraps for chickens and hogs. And meanwhile there was fine sport for all hands.

William Elliott was an aristocratic antebellum planter and these men were his slaves. Not field hands, mind you. These Gullah boatmen were among the best in the world and were treated like African nobility, which they were. With skills honed on the far side of the sea and passed down through the generations, they provided daily transportation for mistress, master and children, and they held the lives of all in their hands. They competed in local regattas and propelled Elliott on many harrowing adventures over the years. Elliott may have doubted the weather, his priming and powder, but never these men.

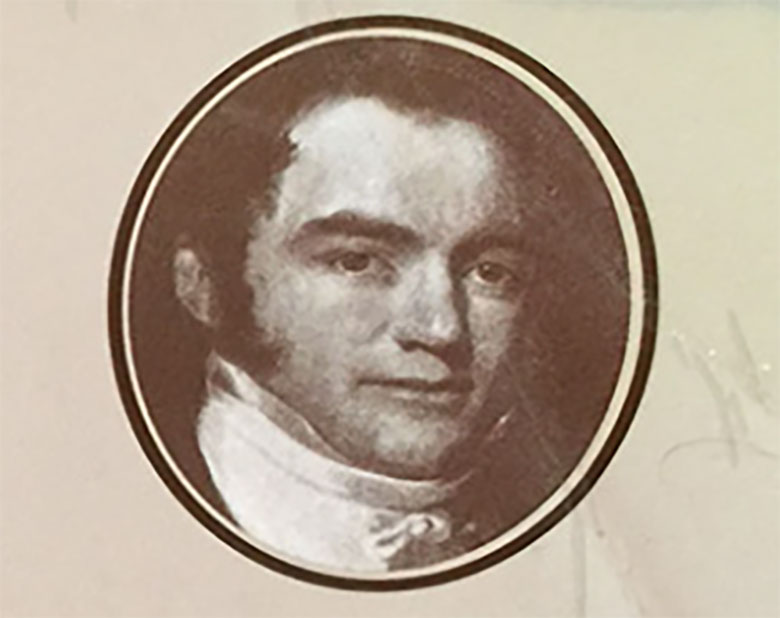

We know this because William Elliott was a writer. Poems, a play, articles about agriculture and politics published in Yankee newspapers, but mostly from his collection, Carolina Sports by Land and Water, including incidents of Devil Fishing, etc., published in Charleston in 1846 and continuously in print thereafter.

I grew up loving Carolina Sports, and a century and a quarter after its initial publication, almost to the day, I got my first paying gig, “Things that Vanish,” a tale of an island deer hunt like Elliott’s. In hindsight, it was hardly that good, but it first saw light of day in a magazine and sometime later was anthologized. It got me a discount on my last semester at Carolina and lastly, won me a full ride to the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, hailed in those days as the nation ‘s best. I had never even pulled the trigger and it became the most profitable deer I never shot.

My grandmother was a lifelong journalist, the first female to be allowed to write beyond the society pages in South Carolina. She had two books published posthumously, and I am damned happy I did not have to wait that long. She was mighty proud of me but wouldn’t let on. She sat me on her porch in the jasmine shade and poured me sweet tea though I was old enough then for a proper drink.

“Now Rogie,” she said, waggling her finger like grandmothers do, “you know printer’s ink is bad as liquor or dope. Once you get a hankering for it, you’ll be hooked for life. And it can skip a generation, too. Is your momma a writer?” She knew the answer and just asked the question to make a point.

“No ma’am,” I said.

“You know I tried to retire twice already.”

“Yes ma’am.”

She had been writing almost a half-century by then, with a weekly column in the Charleston paper. And when she started fresh out of college in 1919, she worked for William Elliott’s grandson, Ambrose.

William Elliott wrote for addictive pleasure rather than money. He was educated at Harvard, tried his hand at politics but resigned his seat in the legislature when it became apparent his constituents expected him to vote for secession. He came back home, looked after his plantations, hunted, fished and wrote. Things seemed about perfect until this Cuban freebooter showed up at his door.

He was Ambrosio Jose Lopez Gonzales, the son of a newspaper publisher, a revolutionary, on the run and a salesman for the famed LeMat grapeshot revolver. Nine shots and then a final blast of buckshot, ten good men with LeMats could break a cavalry change by one hundred, compelling advertising in those days.

Gonzales was the first man to stop a bullet in the cause of Cuban liberty and he proudly bore the scar. He had impeccable manners, was fluent in five languages and was a school chum of the dashing soon-to-be-Confederate-general Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, a widower and native of New Orleans, dubbed by the ladies as “Pretty Good Time Beauregard.”

Pretty good times, indeed.

Ambrosio Gonzales had his eye on Harriet Rutledge Elliott, William Elliott’s daughter. Polite society from Savannah to Charleston was shocked when daddy consented to the nuptials. Gonzales was 38; she was 16. Hattie bore him six children. With writer grandpas on both sides, it’s small wonder three of the children took up the profession.

But meanwhile, the Civil War got in the way. Beauregard fired on Ft. Sumter, won the First Battle of Manassas. He lost the Battle of Shiloh, then successfully defended Charleston from an 18-month Federal siege. At his side during the Charleston campaign was Col. Ambrosio Gonzales, chief of all Confederate artillery, from North Carolina to Florida.

After the surrender, Gonzales took a Spanish pardon and moved Hattie and the children to Cuba. Hattie died there of Yellow Fever in 1869 and Gonzales, struggling financially, sent the children back to South Carolina to live with their aunts on the family’s ruined plantation where they hunted, fished and grew vegetable for the Charleston market.

Two boys, Narciso and Ambrose, learned Morse Code and became “lightning slingers,” or telegraph operators. They moved from transmitting the news to writing it, and in 1891 founded The State soon the most widely read newspaper in South Carolina. They were joined by younger brother William Elliott Gonzales. The Gonzales brothers took issue with Governor “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, a vicious Jim Crow racist. In 1903, unarmed Narciso was gunned down by James Tillman, the lieutenant governor and Pitchfork Ben’s nephew. After Tillman’s acquittal, the jury foreman remarked, “Who ever heard of any jury anywhere convicting anybody for killing a newspaper man?”

Outraged citizens erected a monument to Narciso Gonzales, not on the spot where he was killed, but along the route James Tillman typically walked home for lunch. It stands to this day.

Surviving brothers, Ambrose and William, ran The State for the next 20 years, campaigning against corruption, for equal rights for all citizens, white, black, male or female. In 1922, Ambrose Gonzales published The Black Border, the first of a four-book series about his grandfather’s Gullah slaves and free black neighbors, who turned to subsistence farming, hunting and fishing after the Yankee army laid waste to the coastal plantations. Like his grandfather’s Carolina Sports, The Black Border is still in print and continues to delight lovers of outdoor adventure and authentic Americana.

After enduring his brother’ assassination and founding a major newspaper and nursing it to solvency, Ambrose considered his Black Border series his life’s foremost accomplishment.

But what of the third son, William Elliott Gonzales?

He enlisted in the Army in 1898 to finally free his father’s homeland from Spanish rule. And in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him ambassador to Cuba.

And a fourth son. Yes, Alphonso Beauregard Gonzales was born on the family plantation in 1860 and refused to leave. Join his brothers at The State? No. Run for public office? Definitely not! He was a fisherman, a duck and deer hunter without peer who kept his family and neighbors well fed during chao of Reconstruction. “He was a man of many friends,” his obituary noted in 1908, “and the account of his death brought sorrow to them all. For 17 years he had been in ill health due to an accident . . . but he never lost his cheeriness or his talent as a raconteur and wherever known was a favorite.”

A raconteur? A teller of tales? Isn’t that what writers do?

William Elliott would have been mighty proud.