The indigenous hunting heritage of the Americas should never be forgotten. Perhaps it’s time we learn anew the lessons we should have learned generations ago—from those who learned them first.

“Indigenous Peoples. First Nations. Native Americans. Indians.” There are numerous terms used to reference the first humans to occupy the western hemisphere—as though they are, or for that matter ever were, one collective group. Personally, I have always thought it a misnomer to call these indigenous peoples “Indians”—that they should be encumbered with a such a misappropriated label assigned them due to the gross navigational errors of one misplaced Italian mariner sailing west in a fleet of borrowed Spanish ships, who missed his intended destination of India by two oceans and a continent.

An Ohio arrowhead dated to 8,000-5,000 B.P.

From the Yupik, Inuit and Aleut of the Arctic north, to the Apache, Sioux, Comanche and Navaho of the American West; from the Catawba, Cherokee and Seminole of the southeastern United States, to the Boruca, Aztec and Yucatec Maya of Central America, and all the way south to the Araucan, Inca and Mapuche of the southernmost reaches of Argentina and Chile, the list of peoples who originally occupied the pre-Columbian Americas is virtually endless.

Yet all of them shared the same objectives of procuring and securing the resources and territories necessary for survival, and by the time Eriksson and Columbus arrived, these cultures had already greatly transformed the various ecosystems in which they’d settled to conform to their own purposes.

Philip Hylen, Natural-and-Historic Interpreter for the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC), who regularly presents lectures and interpretive programs on this subject, most accurately points out:

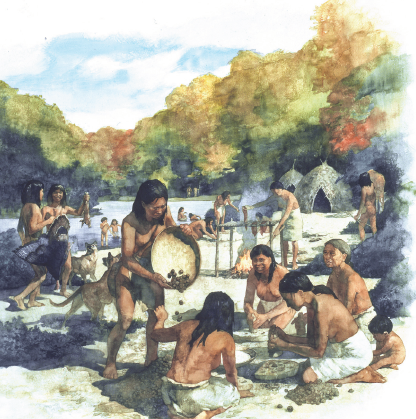

“While people today are becoming ever more aware of the misuse of the term ‘Indian,’ they still have a fundamental misconception as to the nature of the American landscape prior to the introduction of European influence. Most envision the pre-Columbian Americas as an untouched, pristine wilderness, absent the influence of man. But this is far from the truth. The fact is that by the time the first Europeans arrived, the native populations had already significantly transformed the various landscapes and ecosystems they had settled to meet their own individual and collective needs. They were in essence the forefathers of modern land management and conservation.

Signals on the Wind by Brett James Smith

“Today, their ancient practices have become the model for managers and biologists who have rediscovered the foundational environmental principles of the original native populations, who not only honored and respected the land and its resources, but understood that the health of the entire biosphere rests ever so delicately on a balanced and properly organized interplay between man and nature.”

A strong case can be made that we are the humans we are today because long ago these people and their ancestors learned to eat meat. Once considered, the implications are profound.

For not only did they learn to consume their protein directly, they also learned to kill—and this has been a continuing source of human consternation and conflict ever since. Yet killing, for better and for worse, has become an intrinsic part of who we are.

Hunting was an integral component of life for these people. Yet they developed a rigorous and disciplined ethic through which they nurtured, obtained and managed the fauna, flora and other natural resources that underpinned their livelihood—the wood and stone used for tools, weapons and shelter; the nuts, berries and grasses to be gathered at their appointed seasons; the vegetables and fruits to be cultivated and harvested when mature; and the wild fish and game, both big and small, to be taken and utilized to its fullest extent—but only as needed.

This was an ethic long in its establishment, and one they painstakingly nurtured. They had to.

Prior to the introduction of European influence, the indigenous cultures of the Americas had already transformed the ecosystems they inhabited to meet their own individual and collective needs.

For they lived much closer to the land and its resources than the vast majority of those who live today can ever imagine— no freezers, no stores or shops, no banks or investment vehicles or hedge funds.

There were no companies or corporations they could pay to produce their necessities for them, and no brick-and-mortar institutions of learning to which they could send their children to be taught the skills required to survive and thrive. Individual or collective ownership of land was as counterintuitive to them as the concept of owning the air and water, and instead, they thought of themselves as Stewards.

Their operational currency and intellectual capital lay in their own abilities to understand and care for the resources upon which they relied.

It was all about the economics of survival, the abilities and liabilities they possessed, and the insightful management of their assets and resources.

They perceived the world around them as something to be a part of, rather than something they must subdue and conquer. At their best, they possessed a great appreciation for the perfection of the ordinary and the virtues of silence. Life itself was a wonder, and their perceptions and understanding were rooted more in faith and humility and an embedded sense of belonging than in fear and regret.

Their laws and community structure were based on honor, truth and personal integrity and, in some cases, the act of lying was punishable by death.

Individual and community wealth was measured by the materials, tools, knowledge and skills necessary to support their day-to-day living standard, rather than by any stockpiling of excess goods or currency, and hunting lay somewhere among the intermingled realms of necessity, passion, art and even religion. But hunting was most assuredly not a sport.

Nor should it be—either for them, or for those of us who hunt today. Hunting was and is something far more basic and spiritual than mere sport. For at its best and most intense, the hunting experience is a direct encounter with death and life, and without that awareness and spirituality, it is reduced to little more than an idle, self-indulgent pastime.

It is probable that the acquisition of live protein was at first more or less a matter of coincidence and circumstance, if not pure scavenging—taking advantage of other creatures’ kills, and even of accident.

But then, perhaps it occurred to the Leonardo of his age to try and manage or even create specific situations or settings whereby a few of his tastier fellow creatures might be coerced over some cliff or guided into some man-made pit or enclosure or natural ravine.

The advent of actual weaponry was a quantum leap. The advancement from club to stone to sling to spear, and eventually to atlatl and bow, encompasses the vast majority of the human experience, and the invention of gunpowder and the subsequent progression of firearms is a mere blip on the current end of the human timeline.

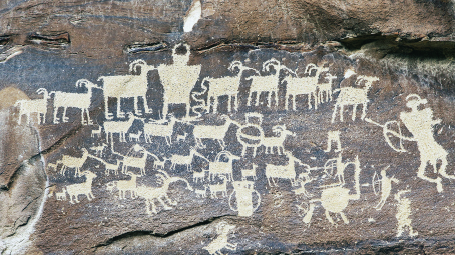

The Great Hunt Panel at Nine Mile Canyon in Utah

Yet the advancement of these concepts and technologies eventually enabled man to become the apex species on this delicate planet we share with so many other life forms—a multitude of whom no longer exist, directly due to our own ascent.

And while we have kept and codified such things as the sling and spear, the atlatl and bow, we have abandoned or lost much of the individual spiritual and managerial ethos that enabled our predecessors to flourish and grow.

Theirs, like ours, was a consumer-driven society. But their methods of acquisition were far more intimate and direct.

I consider myself fortunate, indeed blessed, to remember a time when hunting and fishing and gathering were an important part of our family’s food supply. Whether for live game and fish, or chestnuts, walnuts and wild berries, our elders passed along their knowledge of seasons, locations and techniques to succeeding generations—just as we now pass that knowledge along to those who follow us and care enough to learn.

I’m certain it was much the same for many of you.

Yet, I am equally certain that there is an ever-decreasing number of young people in today’s digital culture who grow up embracing that heritage and perspective, and who therefore have no tangible reason to learn and cherish this valuable but fragile body of knowledge.

An Archaic

Plainview point

from Missouri

This threatens the loss of a treasury of human experience and wisdom that, once gone, will be virtually irretrievable. For the further detached we become from the earth and the resources upon which we rely, the less likely we will be to care about loving and sustaining the planet upon which we are totally dependent. In the end, it begs the question: “What if we couldn’t hunt?” What if we couldn’t fish? What if we couldn’t directly and intimately gather for ourselves the treasures and resources that make us who we are? And what if we couldn’t share such experiences with others or appreciate them for ourselves?

What if we become content to perpetually yield to the ever-expanding constraints of the sprawling urban culture and the infrastructure in which most of us spend the vast majority of our lives, and fall victim to the societal inertia of our own willingness to rely upon others to provide both the necessities and the bounties of life to us—for their own profit, of course.

What if we couldn’t pray? What if there was no pathway, no connection between the temporal and the spiritual, and no open line of communication between ourselves and the Infinite?

How can we permit it?

For the earth is not ours alone. We, just like those who first occupied these lands and called them home, are only temporary occupants, fleetingly dominant though we may be, our tenure tied to the planet of which we are either willing or unwilling custodians, yet often oblivious to the fact that we are the first, and most likely the last, species with the ability to destroy both our habitat and ourselves.

Philip Hylen sums it up best: “Too many people fall under the impression that if we as a human race remove ourselves from nature, it will somehow restore itself to ‘the way it was.’ But humans have always been connected to the land and always will be, no matter how deeply we may take refuge in some self-constructed, self-constrained concrete and asphalt edifice of a city.

“By simply eating, breathing and drinking, man remains a constant factor upon the world. But without a firm and unbiased understanding of the land and water and air and the way they work, there will be no respect. Without respect, there will be no love. And without love, the resources upon which we daily depend will eventually be squandered or selfishly mismanaged, to their and our own ultimate demise.”

Philip Hylen is, of course, absolutely right.

Crows Hunting Buffalo by John Ford Clymer

For we live in a world of ever-growing populations and ever decreasing resources, where the environment has become a political and economic chess piece to be played and, if necessary, sacrificed by people and politicians who are more interested in their own agendas than the good of the fragile planet that provides for those who inhabit it.

Unlike those indigenous peoples who preceded us, much of today’s society views land as a mere commodity to be bought and sold, owned and utilized, regardless of effect. The air and rivers and oceans have become dumping grounds for those who own far too much, and the future is something to be traded away or sold by those who have become disconnected from the age-old rhythms that have sustained the earth and the micro-thin envelope of gases that for eons has protected it and the life it holds from the cold and fire of the Universe.

It is unfortunately a self-prophetic and potentially self-destructive path we tread. But it doesn’t have to remain this way forever.

So instead of resentment and regret, let there be relief and reconciliation. Instead of perpetual conflict, let there be cooperation and understanding. For we are all of the same society, though that society is much too often contentious and fragmented, and tolerance and constructive engagement is in far too short supply.

Let us never forget or abandon, or much worse, apologize for the fact that we are human—as human as the ancestral lines from which we are descended, with all the inherent strengths and weaknesses, successes and flaws that come with the human condition. And let us never dishonor those who walked these lands before us by allowing the loss of the heritage that made us who we are.

Instead, let us try, if we are not already too late, to learn anew and press into play the lessons we should have absorbed and internalized generations ago—from those who learned them first.

For in the end, we are all indigenous peoples.

Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now

Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now