The great naturalist and outdoor philosopher Aldo Leopold once wrote, “There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.” To that I might add that the third is supposing that muskrats are actually little beavers.

While I didn’t grow up on a farm, I did spend my formative years in a town of 4,000, where our playgrounds were the potato fields and creek bottoms of farmland Minnesota. As kids we spent most of our summer days outside, where we chased a wide variety of critters, including each other, all over hill and dale. And we were endlessly bringing home frogs and turtles and various other wondrous creatures we knew would make our mothers squirm.

The point is, even though we weren’t farm kids, we were “of the soil,” and we knew what a beaver was and what a muskrat was, and how to tell them apart, even though we’d never touched either. That didn’t make us special; it just made us small-town kids.

Today I spend much of my year on a river between two lakes. On that river we have an embarrassment of wildlife riches. Mink and otters and fox patrol the shorelines, loons and mallards and herons raise their broods, and deer and bears and even the occasional wolf meander along the course of the waterway. On and in the water, aquatic critters of all kind thrive—including muskrats and beavers.

Which brings me to the Fourth of July weekend earlier this month. As I sat on a dock overlooking the widest portion of the river, a pair of small boats came around a bend in the river. Both were heavily laden with humanity; you might even say overladen. Each little boat looked to have five or six occupants, along with a five- or six-horsepower motor mounted to the stern. All of the aforementioned were running wide open from the sound of it.

The two boats were obviously together, as the occupants were yelling back and forth over the din of the motors. Holidays are like that here, but what caught my attention was that one boat slowed dramatically and the driver starting yelling something peculiar.

“Little beaver! Little beaver!! Little beaver!!! Little beaver!!!! Little beaver!!!!!”

The other boat stopped and spun back toward the first, and when they killed their motors I could hear them all gasp at the sight. They broke out their cell phones for photos and whispered loudly at each other about this beautiful little baby beaver they’d found. The “little beaver” ignored them and floated nearby, munching on cabbage weed.

Of course they were looking at one of our omnipresent muskrats, but boy, were they excited. I could see the little bugger clearly from where I sat, but I didn’t have the heart to tell them that it wasn’t a “little beaver.” Yes, it struck me as funny, and the temptation was strong to dismiss them as city people and make fun of their ignorance of wild things and wild places. But it occurred to me almost as quickly that I was witnessing a vanishing human characteristic.

People are becoming really bad at viewing the natural world around them with awe. As part of my job, I spend a lot of time in national parks, and the way most people choose to view wildlife these days is a mystery to me. For far too many people, wild things are meant only to be seen, casually photographed in a selfie for social media, and checked off a mental list. “Look at me with the cool critter! Don’t you wish you were as adventurous as me?” And then it’s on to other death-defying things.

At least these folks in the little boats cared enough to stop and watch, if only for a few minutes. Most boaters on this river during a holiday week don’t acknowledge anything but the cute girls in the next boat over. I’ve watched them plow through sensitive habitat and run over loons and turtles too many times to count. But these folks, naïve though they were, were inspired to pause and appreciate the world around them. It doesn’t really matter if they got the species wrong.

So, while it wasn’t really a little beaver, it was nature, and the boaters reverence was inspiring, to me at least. My yellow Lab Rosie was there with me on that dock, and she was less inspired. She understands that muskrats aren’t little beavers—she knows full well that they’re really “water squirrels.”

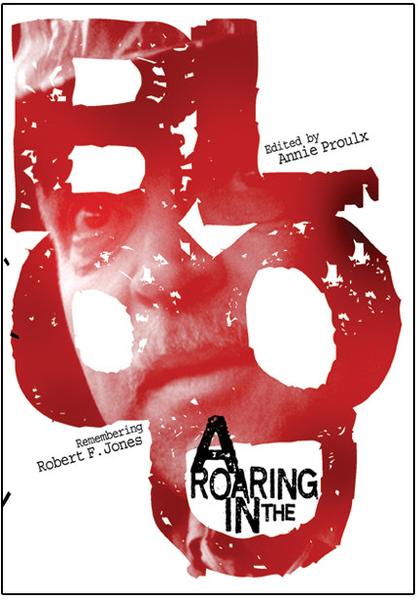

Created and edited by Pulitzer Prize wining author Annie Proulx, this frank, funny, richly textured portrait of legendary writer Robert F. Jones features 15 of his best stories, both fiction and non-fiction. The book also includes 17 wonderful tributes by some of America’s greatest outdoor writers and a collection of Robert Jones’ images by renowned photographer Bill Eppridge. Buy Now