Following a lion on foot locks you into a high-stakes game of hide-and-seek with Africa’s deadliest predator.

Armed with large, bone-crushing teeth and claws that grab like steel hooks, the African lion is one of the most formidable predators on earth. Lions are superb hunters, bringing down large prey by instinctively knowing the best time to launch their attack, an instinct that also works for them in defensive situations.

Lions are also opportunistic feeders, occasionally preying on people once they overcome the man-smell and realize humans are soft and easy to kill. Each year in Africa there are many incidents of man-eating lions, some of which go unreported due to the remoteness of bush villages where the incidents typically take place. Attacks occasionally occur in or near game parks and reserves where, owing to the constant presence of people, lions and other predators have shed their natural fear of man. The parks and reserves are not fenced, and the big predators roam freely in and out of those areas.

Botswana lions are known for their large size, full manes and aggressive nature. They normally bring down larger game to eat, such as giraffe, buffalo and zebra.

Where lions are hunted, being in close proximity to a national park or game reserve can be an advantage, but care must be taken to ensure that all paperwork, licenses and permits are in order as well as boundaries respected.

Bagging a mature, big-maned lion is not only a challenging endeavor, it’s a true test of a hunter’s stamina and ability. If a lion is lean, hungry and minus the distraction of a lioness in heat, all his senses are working for him, which keeps him acutely attuned to his surroundings. As a result, he becomes almost impossible to approach.

There are a couple of circumstances, however, that can greatly increase your chances of getting within shooting range of a lion. The first is after a lion has fed. With a full stomach, his primary interest is finding a shady spot where he can lie down and sleep. A full stomach induces lethargy, which in effect, seems to dull his senses.

The second behavior-altering circumstance happens when a lion goes “a-courting” and his attention becomes riveted on a receptive lioness. In both of those situations, a lion lets his guard down, providing advantage to a hunter attempting to stalk up to him.

You can’t count on finding a lion “drunk on love,” but you can entice him with bait to partake in a meal that will have him looking for a napping spot in the shade.

Traditionally, baiting involves pulling a medium- to large-size game carcass, such as a zebra or buffalo, into a tree and covering it with thorn brush to keep the hyenas and vultures away from it. Choosing the correct location to hang the bait allows you to either stalk up to it or wait in a blind for a lion to approach the bait. As long as the shooting takes place within daylight hours, baiting is considered to be an ethical and sporting method.

Sandy terrain provides hunters with another option—tracking the cat on foot, which is undoubtedly the most exciting and challenging way you can hunt a lion. Coming face-to-face with a lion on his own ground with nothing between you and him but 270 grains of copper bullet gives new meaning to hunting dangerous game.

Pursuing a lion in such a manner is not for the fainthearted. Often, only the flick of an ear or the swish of a tail signifies that the bushy patch of grass only a few feet away is actually a lion’s mane. I spent a number of years hunting lions with safari clients in Botswana, which gave me many opportunities to track the big cats on foot.

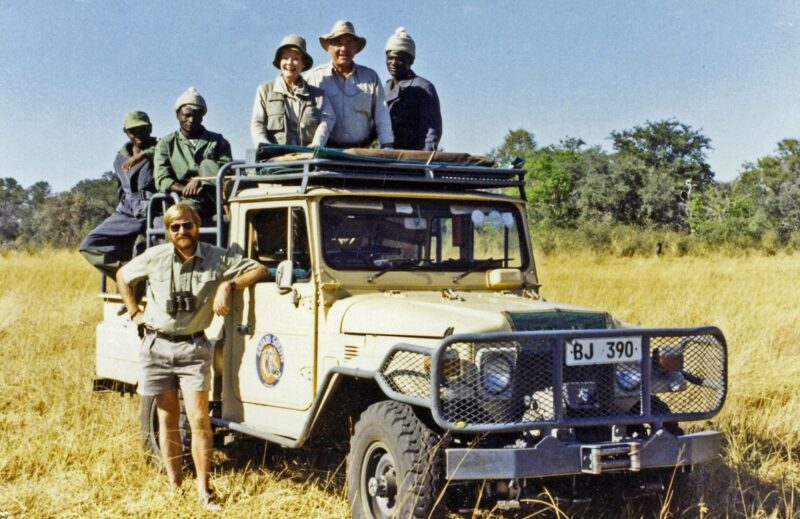

One hunt stands out in my mind for a number of reasons. My client was none other than Robert E. Petersen, CEO of Petersen Publishing Company. Known as “Pete” to his friends, he started his company in the late 1940s, which was destined to become one of the most successful special interest magazine publishing empires in the world.

Pete was an old safari hand who began his African hunting in Uganda back in the early 1960s. By the time he hunted with me in Botswana in 1987, Pete had done safaris in Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Central African Republic and South Africa. He had a lot of big game experience under his belt and it was pleasant to accompany someone on safari with as much game-savvy.

We were halfway through a 21-day safari and our attention was focused on finding a big lion. We had already turned down a couple of young lions and one big old fellow with little more than a Mohawk for a hairstyle.

On our way back to camp one afternoon, we spotted a mob of vultures festooning the acacia trees up ahead, indicating a likely lion kill. Sure enough, we found a dead giraffe killed by lions two days earlier. Vultures in trees and the lack of scavengers lurking about were good signs that the lions were still close by.

A .375 cartridge next to lion’s pugmark in sandy soil is shown for size comparison. The track entails four toe pads forward of a larger pad with three distinct lobes forming an “M” shape.

Studying the numerous tracks on the ground, I could see that a large male was in the mix. I didn’t want to disturb the situation, so I drove a short distance away to glass the surrounding bush and get a lay of the land. I studied the vegetation, noting the location of various termite mounds, bushes and trees. There was plenty of thick bush near the carcass providing lots of places in which the lions could hide.

“Let’s get going,” I told Pete. “I don’t want to disturb these lions. Hopefully they’ll feed for one more night. We’ll be back here in the morning.”

Satisfied with what I saw, I put the vehicle in gear and turned toward a brilliant sunset with a final sliver of sun backlighting the vulture-filled acacia trees. Flocks of storks and ibises drifted past us, flying toward roosts on fig tree islands deep in the Okavango Delta. A sweet grass smell drifted up from the sun-warmed sand as thoughts of a scotch and water over ice sundowner quickened our pace back to camp.

Around the campfire that evening, Pete and I discussed our options for finding the big male lion. I explained the first option, which was an early morning stalk up to the carcass in hopes of finding the lions still feeding on it. We would approach the kill site as if it were bait. If that failed, then the second option was to follow the lion’s tracks into the surrounding bush. We would track him during the mid-day hours when he’d most likely to be sleeping off his big meal.

I have sometimes seen people quickly turn pale with fabricated ailments when faced with the suggestion of following a big lion into thick bush. Although Pete had hunted lions on previous safaris, this would be his first opportunity to track one on foot. I emphasized to him that tracking a lion in thick bush is one of hunting’s greatest thrills—and challenges—but it’s not for everyone. If I had any doubts about Pete’s willingness to venture forth in this type of pursuit, he reassured me by saying that he looked forward to the experience.

Pete and I were awakened at 5:30 the next morning. It was June and a frost had settled on the camp sometime during the night. The temperature hovered at the freezing point as we sipped cups of piping hot tea by the fire. It was still dark when we climbed into the Land Cruiser and drove into the inky blackness beyond the light of the campfire.

My two trackers, Galabone and Sanga, sat in the back of the vehicle, wrapped in heavy wool overcoats. They pulled knitted balaclavas over their heads and faces to break the chill. Both of them were outstanding trackers, proven daily during many years of safari hunting. In spite of having felt the pain of tooth and claw from wounded lions, they both returned to safari work with lion vendettas to settle. Galabone’s encounter had taken place only a couple of years prior to Pete’s safari.

That particular lion had been wounded late one afternoon by a client hunting with Soren Lindstrom. The next day, Soren and I, along with Galabone and Sanga, set out to follow up the wounded cat. After three hours of tense, condition-red work in thick bush, our concentration began to lag, which of course, is when things turned serious. The enraged lion roared and charged in a quick rush from very close range. Soren and I both fired at the lion before he knocked Soren to the ground like a rag doll and brushed by me so close I could have touched him with my hand.

Once the lion was past us, a blood-chilling scream rang out from behind. I whirled to look in horror at the lion’s rear as he mauled one of the trackers. I could not shoot from where I stood for fear of hitting whoever was under the lion. I had only taken three steps toward the lion when he left his victim and I snapped off a shot at his rear end before he was swallowed by thick bush. I ran to the tracker, fearing the worst.

I carefully turned over the body and grimaced at the sight of Galabone’s expressionless face. The top of his head was badly gashed and blood from deep claw wounds seeped through his ripped and torn green overalls. I felt for a pulse in his neck just as his eyelids began to flutter. I silently thanked God he was still alive. We lifted Galabone to his feet and shuffled him over to my vehicle several hundred yards away. We called for an emergency aircraft to pick him up at a nearby dirt strip.

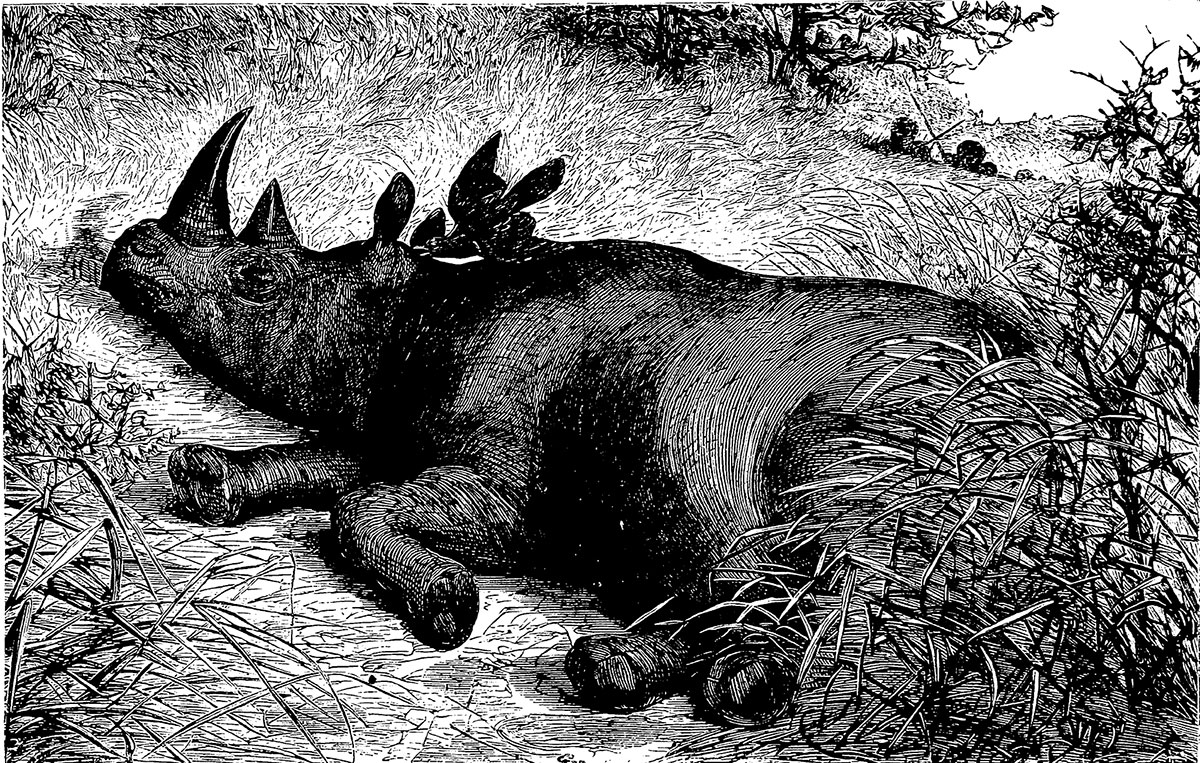

One of the most formidable game animals on earth, lions are armed with large, bone-crushing teeth and claws like steel hooks. They often wear scars from battling each other over food and mating rights.

Soren and I returned to where the attack occurred and had to go back into thick bush to finish the job. The lion charged us one last time before a final shot ended the affair. A little less than a month later, Galabone rejoined Sanga and me on safari and finished the season hunting a couple more lions, now with a score to settle.

Back in the then-present, Pete and I arrived at the dead giraffe that frosty morning only to find a couple of hyenas scuffling and fighting over bones and scraps of skin. The lions had finished feeding on the carcass, leaving it sometime during the night. We planned on returning around mid-day to track the big male.

Around noon, we arrived back at the carcass, but before Pete and I began tracking, I conferred with Galabone and Sanga. They both indicated that we would find this lion, but after that, no one could predict what might happen. Judging by the surrounding bush, it would likely be a close encounter.

When lying on his side, a lion blends in with his surroundings incredibly well. Your biggest concern is to spot the big cat before you get too close to him—close being sometimes only a few feet away.

We checked our rifles one more time to be sure they were loaded with the proper ammunition. Pete’s custom George Hoenig-built .375 H&H caliber rifle was loaded with 270-grain Winchester Power-Points. It was a rifle that accompanied him on most of his hunting trips involving dangerous game—he carried it comfortably and handled it like a trusted friend.

“Are you ready?” I asked before we began tracking. Pete nodded his head yes, and we moved off in single file. From then on, it was only hand signals and facial expressions for communication.

Tracking was not difficult, but because the lion could be anywhere in the thick bush, it was slow, deliberate work. The pale leaves of the mogata trees littered the sandy ground like large, crisp potato chips. As we followed the lion’s distinct pugmarks, the key to being silent was to step into the track of the person in front of you. As point-man, Galabone used the outer edge of his foot to quietly sweep the leaves away from where he would place his weight to step down, a nerve-racking task considering every step brought us closer to the lion.

An hour of tracking had honed our senses to a razor’s sharpness. We watched ahead intently for the slightest sign of the big cat as perspiration beaded on our brows, even though the air was cool. Suddenly, Galabone froze in front of me and I knew he could see the lion. An ear flick had stopped Galabone in his tracks. The lion was only a few feet away lying on his side with his back to us. Slowly Galabone eased back behind Pete and me. His job was done and we didn’t begrudge his moving out of the way.

An hour of tracking had honed our senses to a razor’s sharpness. We watched ahead intently for the slightest sign of the big cat as perspiration beaded on our brows, even though the air was cool. Suddenly, Galabone froze in front of me and I knew he could see the lion. An ear flick had stopped Galabone in his tracks. The lion was only a few feet away lying on his side with his back to us. Slowly Galabone eased back behind Pete and me. His job was done and we didn’t begrudge his moving out of the way.

But we were too close, for if the lion were to suddenly wake up, he would almost surely attack. Pete and I carefully back-stepped to the broad base of a termite mound a few yards behind us. We now had about 10 yards between us and the lion—which was still too close—but going any farther back would obscure our view of the lion.

I could see his mane and I indicated to Pete to aim to the right of it at a spot between the lion’s shoulder blades. That would put the bullet through the backbone and into the heart. Because of the angle, the shot was a tricky one, and we had little time—a shifting breeze could awaken the sleeping lion at any second.

Pete brought the .375 to his shoulder and aimed at the lion. The cat’s tail suddenly lashed, and he may have even begun to sit up when Pete’s shot shattered the silence. As intended, the 270-grain bullet slammed through the backbone and the heart, and then exited between the front legs, throwing up a large cloud of dirt and dust.

The lion roared as Pete quickly reloaded and fired again. The first shot slammed the lion back to the ground and the second shot was for insurance. We waited and watched for any sign of life. Then I signaled for Galabone to toss a stick at the body to see if there was any reaction. There was none, which seemed to confirm the lion was dead.

The case of Henry Poolman came to my mind. Poolman was a Kenya professional hunter whose client, back in 1966, had shot a lion that went down, appearing to be stone dead. The animal showed no reaction when a tracker bounced a stick off the body. As Poolman stepped forward, the lion suddenly leapt to its feet and charged. Poolman quickly put himself between the on-coming lion and his client. Just then, one his trackers who was carrying a shotgun fired at the lion. A full load of buckshot hit Poolman in the chest, killing him instantly.

I knew from a couple of my own close calls with charging lions that when it happens, it happens fast—but a charge of buckshot is even faster—and deadlier.

Cautiously, we eased up to the lion from the tail end and I prodded him with my rifle barrel—he was indeed dead. He seemed to grow bigger as we got closer and when we put our rifles down, the back-slapping, hand-shaking and cheering broke out like steam from a pressure cooker.

Moving him was not easy, much like dragging a 500-pound bag of wet sand, though nobody complained. While Pete relaxed and admired the big lion, Galabone and I hiked back to the Land Cruiser. Our slow, tedious tracking had taken two hours; the walk back took only 20 minutes.

The experience was still sinking in for Pete when we drove into camp where the crew came running and shouting to congratulate and thank him for killing the lion. There’s little love for lions among those living in the African bush where they’re regarded as the devil himself. In camp, a lion’s demise is enthusiastically celebrated with much dancing and singing.

For Pete, having hunted a lion in the most sporting manner possible, there was great elation, tremendous relief, but also a twinge of regret over the sudden end to a magnificent animal’s life. These are a normal range of emotions felt by those who take up the challenge and danger of tracking the king of beasts on foot.

John Banovich believes he was born to tell the lion’s story—from its ancient past to its troubling future. And in the new KING OF BEASTS, a strikingly beautiful 12- by 11-inch book, he tells that story the best way he knows how—by painting Africa’s most storied predator.

John Banovich believes he was born to tell the lion’s story—from its ancient past to its troubling future. And in the new KING OF BEASTS, a strikingly beautiful 12- by 11-inch book, he tells that story the best way he knows how—by painting Africa’s most storied predator.

Over his illustrious 26-year career as one of the world’s foremost wildlife artists, John has continued to draw and paint the African lion more than any other subject, simply because no other animal speaks to him quite the same way.

From LiveOak Press, publishers of Sporting Classics, King of Beasts – A Study of the African Lion showcases 134 stunning color plates and 20 drawings of the lion and the many fascinating creatures that share the big cat’s wild domain.

Written by David Cabela, an expert on conservation, wildlife and things Africa, King of Beasts pays homage to not only to lions but also to Banovich and his remarkable achievements in art and conservation. Two editions available, each signed by John Banovich. Buy Now