Don’t think of Linda as some sort of five-foot-four female Indiana Jones who’s hellbent on adventure. Rather, she’s a rare spirit who is both good and lucky, an unbearable combination for a wildlife artist.

The leopard had appeared fairly tame. Reared on a South African ranch that breeds an rehabilitates big cats for ultimate release onto the plains, the leopard an her handler ambled along with a group of artists who had come to take those close-up photos they use for inspiration and reference in their studios back home.

One of the artists was Linda Besse.

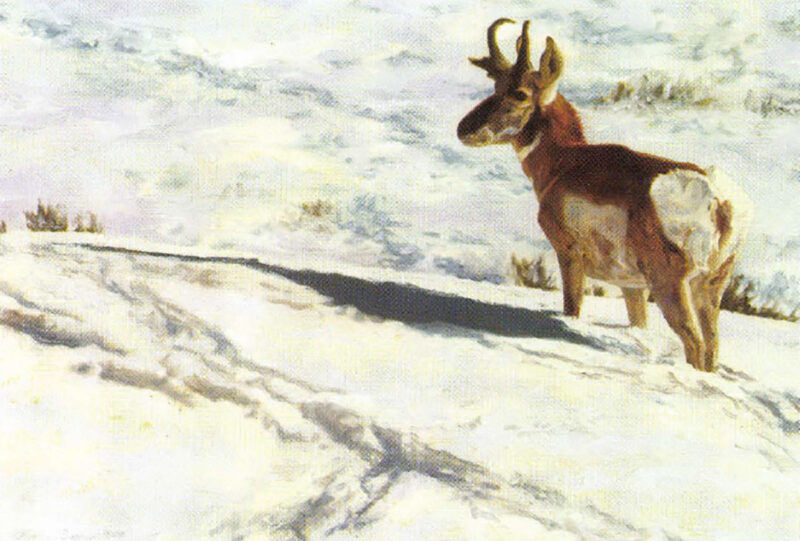

Tracks

The next day, they returned for another photo session. No longer docile, the leopard frisked, crouched and swatter the air the way playful house cats do when they’re happy. She leaped into a tree and froze, poised on a branch, perfectly backlit against the rising morning sun. Linda eased away from the group, hoping to get a different angle. She slid around the tree, raised her camera and started shooting.

Suddenly the leopard jumped down from the tree and padded toward her. Linda stayed calm, waiting for the cat to pass. Instead, it came closer. So busy was she observing the rolling movements of its shoulders and the intensity of its piercing eyes that, at first, the leopard’s spring did not register. The cat reared up , encircling Linda’s neck with its big paws and pressing its head against her ear.

“We dance that way for a moment or two,” she remembers, “and then she was gone.”

Only when the handler, breathless and fearing the worst, rushed up and asked: “Did she use her claws?” was Linda aware of just how close she had been to being mauled.

Linda attracts adventure the way a hot IPO draws investors. In recent years she was dropped off on an Alaskan mountain by a helicopter. She climbed to the top of a Mayan temple in Tikal, Guatemala, and visited the Iceland nesting grounds of the skua, a fierce, oceanic predator that feeds on the young of other birds. Things haven’t always gone as planned.

Polar Chase

Take her 70-kilometer canoe trek down the Zambezi River in Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools National Park. Alive with crocs and hippos, the water turned glossy as fresh tar as soon the sun dropped behind the hills. Linda and her partner, equally novice canoeists, paddled with enthusiasm spurred on, perhaps, by the knowledge that on average, two people are killed along this stretch of river every year.

“Our guide told us that if a hippo struck the canoe, we should stay with the wreckage,” Linda laughs with just a hint of the same nervousness she must have felt that night. “He said that if we tried to swim for it, we would surely be attacked by crocodiles.”

Steaks of copper moonlight rode the curls of waves from the canoe ahead. Trees loomed black as coal against swirls of stars deep in the gun-blue sky. “Hippo! Hippo! Quick, quick, back-paddle, back-paddle,” the guide’s stage-whispered instructions cut the night.

Frantically, they thrust their paddles into the current, careening around the bulky dark mass that had risen from the depths and sprintingf or the riverbank where they crashed with a jarring thud. Hippo skirted, they made for camp where they were soon asleep, oblivious to the roars of lions in the distance.

Lord and Master

Don’t think of Linda as some sort of five-foot-four female Indiana Jones who’s hellbent on adventure. Rather, she’s a rare spirit who is both good and lucky, an unbearable combination for a wildlife artist. Add on that a person who is super disciplined and incredibly organized. Given a moment, she will tell you how she has organized her 22,000 photographs in a cross-referenced card file and how when she wants, say, to look at pictures of elk, she can quickly find every elk photo she’s ever taken in the fifteen years since she first picked up a brush.

Holly Frye, a friend of more than a decade and owner of Pacific Flyway Gallery in Spokane, says that Linda paints water better than anyone else. “She accomplishes this through the judicious use of a natural palette, but with unusual highlights,” says Holly. “You’ll see golds and purples in water that you and I would just normally see as brown and green.”

Linda is driven by an intense determination, whether on a wilderness outing or in her studio. She is generally at her easel shortly after the sun’s first rays spread through the pine, spruce and tamarack trees that crowd the ridge behind her studio a half-hour north of Spokane. She puts in a solid day, perhaps working on a miniature or doing the tawny grasses in Lord and Master, a 30- x 48-inchpainting. She paints only in oils, using a wet-on-wet technique that gives her better control of color and texture.

“Linda is very impressionistic in a lot of ways,” says Gamini Ratnavira, a SriLankan nature artist now living in California. “She is able to capture the soul of an animal. If it’s a lion, the aggression; if it’s an antelope, the docility. She gets all of the emotion in the animals she works with. It can’t be done unless you have good experiences.”

Clouds of brown dirt fog the hindquarters of the elephant in Zambezi Thunder. I like this painting because it catches the beast in a moment that is so obviously unposed. “There’s a lot of movement there,” observes Gamini. “Linda creates emotion by not really making her lines sharp. She gives a nice vibration between the subject and the background.”

Tyger

Linda had so admired Gamilli’s wildlife portraits with their tinge of Eastern mysticism that she bought an original in the late 19805. Then, in 1998 Gamini offered to be her mentor and Linda jumped at the chance. He was impressed with her discipline and knew that she had the light qualities — the drive, the sense of color and composition, the yen to travel to see animals in their natural environs — so necessary to becoming a successful wildlife artist. Gamini’s style is dramatically different from Linda’s, but he is perceptive, and through a hint here, a gentle nudge there, and occasionally a firm push, he opened the doors that allowed her to develop her own style.

“I can go to a wildlife show and see 20 artists that are painting the same subjects, and I won’t be able to tell one from another,” says Gamini. “Linda has her own style — an impressionistic way of filling her paintings with a lot of movement. You can easily see the difference between her work and that of other artists.”

Gamini is obviously proud of his pupil. He attributes Linda’s success to her powers of observation, her penchant for detail and her rigorous self-discipline. Among important measures of Linda’s talent is her inclusion in major exhibits at Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum; Bennington Center for the Arts; Holland and Holland in Manhattan; Art of the Hunt Gallery in Greenwich, New York; Safari Club International and the Waterfowl Festival in Easton.

Linda’s sense of focus first emerged at Colgate University where she trained as a geologist with an emphasis on geochemistry. She was as fascinated by the beauty of microscopic crystalline structures of rock as she was by the formula which described their composition.

She met her husband Jim twenty-four years ago after moving to Washington state where she earned her master’s degree in geochemistry. Jim was also a geologist and both had a nose for gold. Linda’s thesis focused on the process of identifying ways to find Carlin (non-vein) gold deposits. Later, as a consulting geologist, Jim located a pair of deposits in the US and traveled extensively in Peru.

Jim’s travels, however, kept the couple apart. “He was gone for 260 days a year!” Linda recalls. ”We wanted more time together.” They remained in Spokane because they loved the countryside. Linda had created a successful career in real estate by then, so Jim phased out his geology consulting business and, with a partner, now designs and builds custom homes. Among them is their house and Linda’s “dream studio” next door.

Unaware of her talent, Linda had never picked up a paintbrush until the week following a vacation with Jim in Hawaii. “I saw a painter doing an outdoor scene. It looked like fun, so I went out and bought what I needed to get started.” That was in 1990.

Still selling real estate, Linda produced only two paintings a year until 1996. Then the bug bit, and a painting a month flowed from her studio. In ’98, she held her first show and a year later began painting full time.

Today, when Linda sets out to paint an animal, she is thinking primarily of how to convey it as an individual rather than as a stereotypical representative of its species.” I don’t want to paint just any leopard, bison or bobcat, but a particular one,” she insists. ”What was the animal feeling? What mood can I see in its subtle body language? If I was this animal at this moment, what would be my dominate emotion?”

I try not to project my own human thoughts, but to step aside and let the animal’s shine through. Then, I’m challenged to display and even enhance that dominate emotion as I build the rest of the painting.”

So how do you learn all these things about an individual animal? You let the animal show you.

Driving in Yellowstone National Park, Linda glimpsed something out of the corner of her eye. Pulling off the road, she spotted a coyote about 30 yards away. “He was magnificent,” she remembers. “It was just before wolves were introduced into the park, and this guy was still at the top of the food chain. He came closer and I just sat there, trying not to spook him. He explored the area around me, sniffed under a log, yawned and scratched his ear, even posed with his front paws on the log. I was able to watch him for about twenty minutes before he moved on.

“This is the kind of encounter that influences my art. It was a chance to observe a wild creature acting completely natural … to see how he moved and interacted with his environment. Those moments are priceless.”

Drawing from wild encounters such as this, Linda now creates about thirty paintings a year. She uses her miniature works to explore new designs, new subjects and new colors. Of the miniatures, she says, “You have to make a lot more decisions about how much detail to put in. You don’t just want to use tiny brushes to fill it in. Maybe there’s an economy found in a smaller piece as you work out the details. Per square foot, it takes more work to do a smaller piece than a larger one.

“When I do a small painting, I might sit there and work for eight hours straight. On a larger piece, I’ll work for three hours, take an hour break, come back to it, work a little bit more. I’ll spend more time thinking.”

High Stakes (detail)

During her breaks, she will often set the painting on an easel across the studio from her perch on a bench seat or the couch. She’ll be reading about the subject of her painting or how other artists have solved problems in their pictures, and she’ll glance up — just for a moment — and then look away, much in the manner of freezing the frame in a video.” In that instant, I might see the need for a little more color here, or the need to be lighter there. It’s like a set of continuous first impressions. It’s a good way to get a break and have a fresh perspective.”

Also during her breaks, Linda will devote time to the business side of her career. Hal duPont, owner of Western Masters, Inc. gallery and an importer of Krieghoff shotguns and rifles, will be the first to tell you that Linda is very savvy when it comes to the four “Ps” — product, price, place and promotion — of marketing art.

Linda is as diligent in producing originals that range in price from $500 to $25,000 as she is in offering them in a range of sizes that can be attractively hung in houses no grander than yours or mine. Producing a newsletter, Website and brochures and maintaining personal contact with customers and dealers and galleries — all are addressed in her marketing plan.

Gamini Ratnavira says it’s rare to find an artist with Linda’s touch and feel for painting combined with such astute business sense. Yet sales of paintings finance her adventures. As this issue goes to press, she’s deep in the wilds of New Zealand observing red stags and birds. Next summer will find her hunched in a kayak, photographing polar bears and beluga whales in the sub-Arctic north of Churchill, Manitoba. She’s laying plans for fishing steelhead and salmon on Vancouver Island and a return bout with elephants and lions in Zambia and Tanzania. Safe enough these treks would be if you or I made them. But remember Linda’s penchant for dancing with danger.

On these pages you will discover 134 paintings and 20 sketches of lions and other beasts of the veldt. Every one of these captivating images originated in Africa, where John has observed and, in some cases, studied more than 2,500 individual lions in the wild. Buy Now

On these pages you will discover 134 paintings and 20 sketches of lions and other beasts of the veldt. Every one of these captivating images originated in Africa, where John has observed and, in some cases, studied more than 2,500 individual lions in the wild. Buy Now