Hunters and anglers are particularly vulnerable to these fiery sky wires.

Around 6 a.m. on Sunday, November 5, 2017, Curtis Atkins and one of his hunting buddies sat in their truck near Zanesville, Ohio, debating whether to hunt. Skies had been variably cloudy during the night. Rain was in the forecast, and to the west a half-hour earlier, they’d seen flickers of lightning. But the skies seemed to be clearing.

Ohio hunter Curtis Atkins stands next to his ladder stand and the tree that was struck by a bolt of lightning, knocking him unconscious.

By 6:30, Atkins had settled into his ladder stand against a tree on a rise overlooking a well-worn deer trail with heavy rubs nearby. Drizzle began five minutes later. He wasn’t about to let a little rain bother him. Bow season would end in a couple weeks, and he was eager to fill his deer tag before rifle hunters crowded the countryside.

Moments later, a bright blue-white light filled the woods. Curtis never saw it. At the instant of the flash, he blacked out. Unconscious for only a minute or two, he awakened to the smell of burning skin. His. Oddly the bolt of lightning that struck his tree didn’t blast him from his stand.

He stumbled out of the woods, and his buddy drove him to Genesis Hospital. Doctors treated burns on his hands and the left side of his face, according to an article by Kate Snyder in the Zaneville Times Recorder, and for “an entrance wound and three exit wounds in his back.” Vision in his left eye was blurry, and Atkins remembers feeling that his head was on fire.

By the following Thursday, Atkins was back on his treestand, which his wife calls a 20-foot lightning rod. He’s vowed, however, never again to hunt in the rain.

Ed Singleton wasn’t so lucky. He and his pal, Tom Brown, were fishing in a Bass Rattlers Association tournament on Lake Okechobee on June 8, 2013. As Brown tells it, they were out in Ed’s boat when “the first bit of lightning showed.” They stowed their rods and lit out full throttle for the dock. Just 30 seconds later, the boat was struck, knocking both anglers unconscious.

Brown came to first. A retired fireman with 27 years’ service, he immediately tried to revive his friend. “That was the hardest time I ever had to do CPR in my whole career,” he said. Singleton was transported to Hendry County Medical Center where he was pronounced dead.

Brown came to first. A retired fireman with 27 years’ service, he immediately tried to revive his friend. “That was the hardest time I ever had to do CPR in my whole career,” he said. Singleton was transported to Hendry County Medical Center where he was pronounced dead.

Equestrians, especially those riding in open country where they are the tallest thing around, can be susceptible to lightning strikes, as well. While riding on a rural road near Sedalia, Colorado, Laural Miller and her horse were killed when a bolt of lightning hit a tree about 15 feet away.

While pheasant hunting in South Dakota, a good friend’s father saw lightning strike a fence a short distance ahead. He watched, completely enthralled, as a ball of fire came spinning toward him along the top wire. The brightly glowing orb danced right past him and continued for another 50 feet or so before suddenly fizzling out. He was lucky. A side or ground current could have traveled up his boots with tragic results.

The odds of being struck by lightning vary by year but are roughly one in 800,000. During an average lifetime, the odds narrow to roughly one in 3,000. In 2017, only 16 lightning-related deaths were recorded. A decade earlier, the number was 47 in one year. Most lightning deaths occur in the Southeast due to prevailing weather patterns.

St. Elmo’s Fire on Airbus windshield.

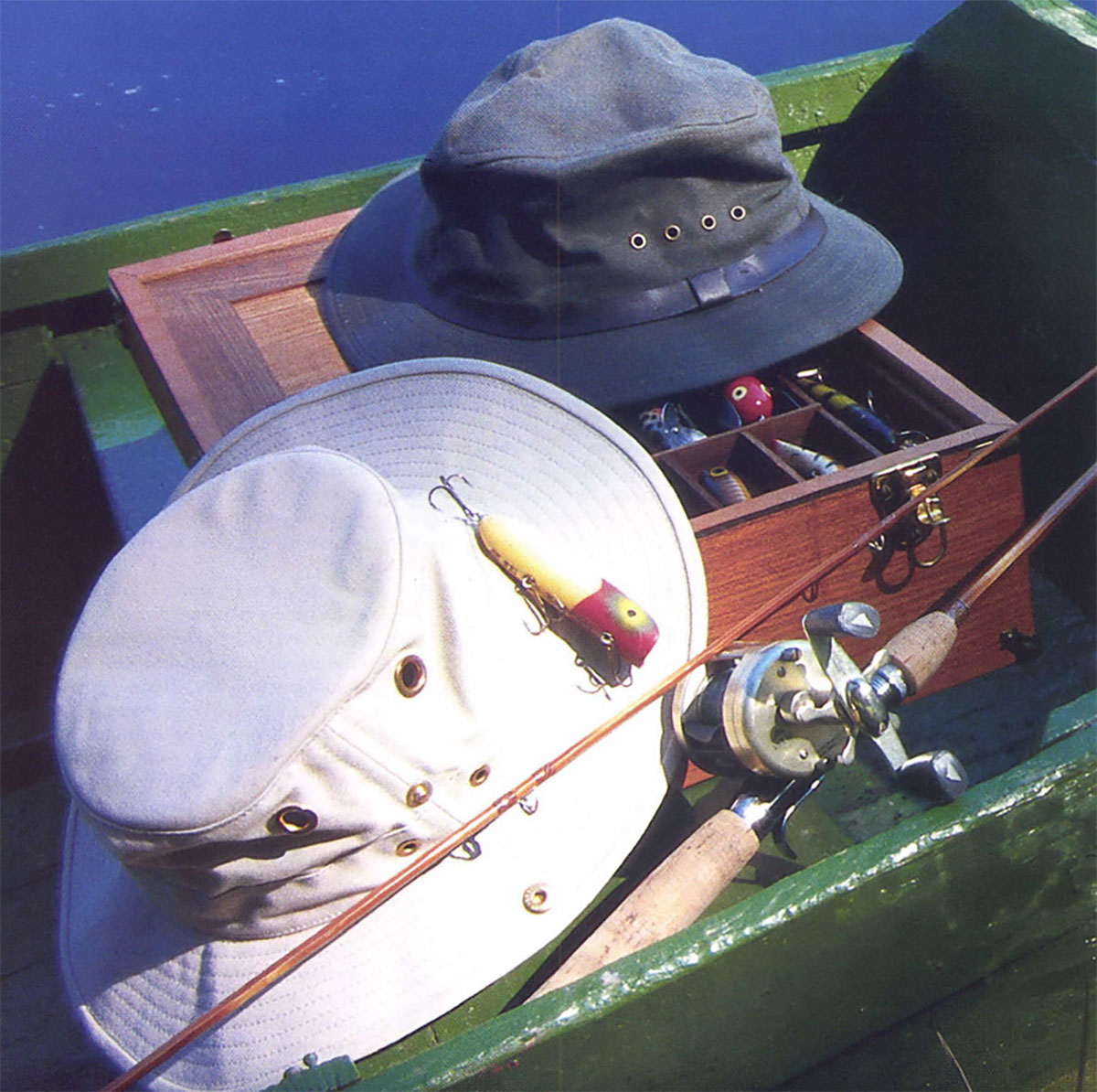

Anglers are far more likely to be struck by lightning than hunters, according to records kept by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA). From 2006 to 2017, leisure activities accounted for 63 percent of lightning fatalities. The biggest group of those, 34, were related to fishing, not just from boats, but also from docks and on shorelines.

Thinking back, I’ve come close to being struck a number of times. Our Boy Scout troop canoed the lower Little Tennessee River at least once each summer before it was impounded by Tellico Dam. On one trip, we were about three miles from our campsite when a line of thunderstorms brewed up. Lightning zapped the hills on both sides of the river. After each strike, particles glowed like embers hanging in its wake, and the air was heavy with the pungent smell of ozone. I was mesmerized and fascinated.

A few years later, a pal and I were floating the Nolichucky River in Greene County, Tennessee, for smallmouth bass in my Alumacraft jon boat. We heard a heavy rumble of thunder and felt the wind pick up, so we drove to under a tall cliff. The thunder grew louder and louder. Grasping the gunnel, I could feel pulsing voltage. A bright flash illuminated the barn in the field across the river followed not a second later by a piercing crash of thunder. Through the rain, we could see the silo smoldering.

A decade or so later, my sons and I had another hair-raising encounter with lightning. We were hiking from Clingman’s Dome, the highest point in Great Smoky Mountains National Park via Thunderhead and Spence Field on our way to Cades Cove. Midsummer thunderstorms in the Smokies are the norm. After lunch, the sky darkened. Son Seth was carrying the steel pruning saw we planned to use to cut wood when we camped for the night. We quickened our pace, hoping to make the shelter at Siler’s Bald before it poured.

We didn’t make it. Rain was so heavy that the trail ran about afoot deep with water. Lightning began to crash down on the peaks around us.

“Drop the saw!” I hollered to Seth. He did and when I bent to pick it up, my hand felt as if I’d just grasped a live 110-volt wire. I immediately dropped it, and we hustled down into a low gap between two peaks, knowing that lightning was most likely to strike the highest point on the terrain, not us.

St. Elmo’s Fire across cockpit windshield.

Lightning is superheated ionized particles of air marking the path of an electric charge leaping between negative and positive poles in clouds or between clouds and the ground. Thunder is noise caused by rapid expansion of air superheated by lightning, somewhat like the shockwave of a sonic boom. Lightning’s much more benign cousin, St. Elmo’s Fire, is well known among ocean sailors and pilots, though it occasionally makes a dazzling appearance on the ground.

Anglers are generally pretty good at reading water. We immediately pick up rises of fish feeding on the surface. We can also see subtleties, like what I call “nervous water” caused by the wakes of baitfish being chased by predators. These little ripples run counter to wave patterns raised by breezes.

We should be equally adept at reading weather. Like Rodney Dangerfield, meteorologists “don’t get no respect.” Yet the accuracy of five-day weather forecasts is 90 percent, according to NOAA. All of us carry cell phones, on which we can pick up excellent weather forecasts from NOAA and the Weather Channel, in addition to radar data that’s often no more than an hour or two old. Whether we heed it or not is up to us.

Ever since I saw lightning strike that barn, I’ve been very conscious of weather while hunting or fishing. My interest sharpened during research for my latest book, The Forecast for D-Day and the Weatherman behind Ike’s Greatest Gamble. These days, I pay serious attention to the tracks of high- and low-pressure cells and their attendant cold and warm fronts.

Still, when planning a trip, this old children’s nursery rhyme governs my preparations:

Whether the weather be cold, Whether the weather be hot, We’ll weather the weather whatever the weather, whether we like it or not.

If weather radar shows approaching thunderstorms, and forecasters broadcast severe weather watches and warnings, I pay attention. Without putting too fine a point on it, a “watch” reports the potential for severe weather. A “warning” reports that such weather has been observed and may be headed in my direction.

If weather radar shows approaching thunderstorms, and forecasters broadcast severe weather watches and warnings, I pay attention. Without putting too fine a point on it, a “watch” reports the potential for severe weather. A “warning” reports that such weather has been observed and may be headed in my direction.

The sky also tells the story. Dark clouds are called ominous for a reason. Watch their movement. Pick a stationary object like a tree or a steeple and, in comparison, track the speed and direction. Ditto with those grey veils of rain falling in the distance. If the weather starts looking nasty and you can’t take shelter in a vehicle or building, make tracks for the lowest spot wherever you are. If you’re caught out in the open while, say upland bird hunting, find a swale, lay your shotgun down flat, squat, hug your dog and let the squall pass.

If you’re fishing in a boat and can’t get to shore, lower all rods and antennae. Disconnect VHF radios, fish finders and other electronic gear. Hunker down without touching any metal fittings, but maintain power to keep the bow pointed into the wind. Though it would seem that fishing on a mountain trout stream surrounded by high peaks and tall trees would offer ample protection, you might not be as safe as you’d think.

Classic thunderstorms are mini-cyclones and lines of severe thunderstorms may be accompanied by violent downdrafts called microbursts. While trout fishing in the Smokies, I felt I’d be pretty safe surrounded by high mountains when the skies darkened and the wind picked up. Instead of hiking the half-mile to the car, I crouched behind a big boulder. All went well until a vicious gust felled an old tree not 25 yards from where I sat. Next time I’ll wuss it out and make for the car.

Essential Hunting And Survival Skills From The World’s Elite Forces

Essential Hunting And Survival Skills From The World’s Elite Forces

Elite Forces Handbook of Hunting and Shooting demonstrates the core skills involved in being a self-reliant hunter. Includes detailed illustrations from tracking large game to shooting wild pheasant, this book is the essential guide to finding, killing and surviving off animals in the wild. Buy Now