Poetic justice, I thought — that on the same mountain where I’d shot that bull in the heart before, I got hit in the heart.

About mid-morning on a Montana mountainside the guide heard “Cody, just a minute.” He turned to see the hunter lean forward, then fall straight back.

About mid-morning on a Montana mountainside the guide heard “Cody, just a minute.” He turned to see the hunter lean forward, then fall straight back.

Cody got the hunter’s rifle out from under him, kneeled over, called his name, saw he wasn’t breathing and found no pulse. Then he saw and heard a sound he says he won’t ever forget — a gasp. The hunter died.

Cody immediately applied CPR for three or four minutes — he said it seemed like an hour — which brought breathing and a pulse. He waited five or 10 minutes, then learned close and said, ‘I’ll go for help.” The hunter, unable to speak, blinked both eyes.

I lay there an hour.

With no memory of any of it, I learned later from Cody that he had turned me on my side when I showed signs of vomiting. That is to be expected with very low blood pressure, since my circulation had just been restored. The vomit was mostly saliva and mucous — none of the Milk Way candy bars we have just enjoyed. He supported my head with his seat pad (for sitting on snow), rolled up my collar and placed my hat back on my head. Then, he covered my body with Polar Fleece from his pack. Finally, Cody marked the spot by laying his hunter-orange vest atop a tall sage bush.

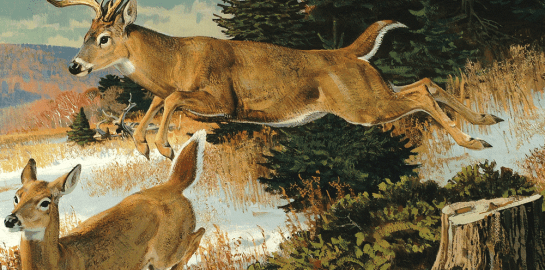

We had been stalking two bunches of elk up high. The first had been scattered by another hunter. We had gotten within range of the second group of seven, but found no legal bulls. We had been hiking back to the truck, still a mile-and-a-half away, crossing a great hillside of sage when my heart gave out. The bushes around me, all about the same height, would hide the largest of men and most animals lying down. Without the orange, I’d have been hard to find. Even with it, one would have to get fairly close.

Cody ran down the mountain, then slowed when his own chest started to complain. He skidded his truck into the Harrison ranch yard, six miles down the road. Ted and John Harrison came out of the shop. Cody yelled, “Get an ambulance. Quick.” Then he phoned the Rapid Response Team at the Circle S ranch.

With John Harrison aboard, he raced there, about nine miles, to guide the EMTs to me. When Cody saw his footprints in the snow, he jumped out to walk lead. At about 200 yards, he spotted the orange vest and waved the truck toward it.

I was found, still unconscious, a short distance and at a right angle from where Cody had left me. The Polar Fleece was under my head. My old, much-exercised heart must have been working well enough for me first to think about moving and then to actually crawl a few feet.

From that point on I was given oxygen, transported by Chevy Avalanche to Pole Creek where the ambulance waited, unable to get across. On a pack board, my 160 pounds made an easy crossing. But they told me I was combative when they put me in the ambulance. Don’t know why. It may have been my reaction to the EMTs cutting my clothes off. They do that for fast access to blood vessels, etc. In my belongings, my wife found my Filson wool hunting pants and a fine shirt in shreds. Good thermal long underwear, too. Damn!

Leaving that mountain this time contrasted sharply with the thrilling, full-filled experience I’d had before, when in near dark I took the bull at about 300 yards high above. Hit in the heart, it was a shot beyond my ability, bordering on miraculous. This time it was I who was dragged out.

My wife arrived the next day. Poor dear, all she knew was that I was unconscious. My good color, open arms and, ”I’m just fine,” relieved her some. But in the four hours she was with me that evening, I asked her what day it was five times.

Cody came to see how I was getting along. I said, “I think I have a couple of days left of my hunt.” He didn’t get to answer. Mary disagreed very quickly.

After three days in the Butte hospital’s ICU where both my wife and I were treated with loving care, I was flown home for evaluation, heart surgery and fancy electrical regulation of the heart rhythm.

Working to regain my injured short-term memory, I learned the nurses’ names as they came and went. Everyone was thanked by name for interrupting me, waking me or sticking me.

Working to regain my injured short-term memory, I learned the nurses’ names as they came and went. Everyone was thanked by name for interrupting me, waking me or sticking me.

While I was still in cardiac intensive care, a male nurse, on learning of my experience, invited me to hunt elk with him next year. The hospital has since repaired the ceiling of the room where I told Mary of the invite.

Day after day I was “up,” in good spirits and high appreciation. I was euphoric, a sort of continuing high and I wondered why. Was it appreciation for being alive, appreciation for the great care or the effect of hundreds of people praying for me? Whatever, I loved it. I also thought it might not last. And it didn’t.

Depression set in. I knew to expect it but seeing my thin body now looking like a prisoner of Japan in WWII, feeling strength gone and with life dependent on an electronic device, dark thoughts came. Probably I had missed my best chance to depart this earth perfectly — without pain, fear or worry. Quickly. Doing what I loved. Now, I’d have to wait for another system to fail, maybe slowly.

Poetic justice, I thought — that on the same mountain where I’d hunted before, I got hit in the heart. On that earlier deep-dusk kill, my bullet had torn part of the bull’s heart away. Heart for heart. But mine stayed whole and got a jump start.

It wasn’t all “down.” For one procedure, a heart catheterization, two nurses leaned over my groin. I felt them rub, shave and paint. Raising my head, looking hard at them, I said sternly, “Girls, I’m going to tell my wife what you’re doing to me.” A laugh and then sleep.

For several weeks negative thoughts would spring up through the fatigue. Realizing that depression was to be expected didn’t alleviate it. Reasoning that I was extremely lucky to be alive didn’t help. Then, on Christmas eve, things changed.

On the floor in front of the fire, twin Grandsons gave me a back rub. Those small hands touching my back, rubbing without prompting, brought a surge of thankfulness. I turned the corner. Then, with the full realization that I had been given another chance, a new lease on life, I wondered, as I have many times throughout my life, why I have been so lucky — spared in WWII and, now. Why me Lord?

People ask if I had any images, death visions, out of body type. If I did, I don’t remember them. My last recall is tying my down jacket sleeves around my waist before climbing in the predawn.

But lying there, I must have had thoughts. I was aware enough to blink acknowledgement that Cody was leaving. I moved, made a head support from the Polar Fleece. What did I “see?” What were my thoughts? Survival thoughts seem reasonable now, but the brain’s chemistry for memory was gone. Short-term memory goes first in old age and from physical or physiological trauma.

Perhaps I wanted to get out and didn’t have the strength, but I did have the sense to stay put. I must have felt alone, but having spent many, many hours alone on a snowy mountain, I could handle that. Were my thoughts focused on my heart? Doubtful. In the Butte hospital I argued with the doctor, “I didn’t have a heart attack. Couldn’t have.” I’d felt so invincible from years of exercise and nutrition-conscious eating. Oh, to have recall of that hour alone on the snow. But it might be better this way.

From the leisure of healing, before busyness returns, there is time for thought and there is an enhanced sense of awareness — to see everything almost for the first time, actual sights and smells and memories.

And one comes full circle to what mankind forever has pondered: the meaning of life. We live, learn, work and play mostly for ourselves. Yes, we do help others, some even to the point of giving their lives, but so much time passes without notice. Seldom do we get outside of ourselves. I wonder … How can I make my second life more worthwhile?

Facing a year without venison, during long nights, wakeful hours I plotted. A plan evolved. Last year, at the ranch where I had permission, I’d walked to the logs which I had previously pulled to the fence-line close enough to the grand old buck’s corner of the vast winter wheat field. I napped, then awoke to find instead of the usual thirty to forty deer, the field was empty. Apparently, some deer watch that field all day.

My scheme, my plot, based on the fact that deer can’t count, involves the ranch foreman and his vehicle — familiar sight and sound. He could drive me to the blind, get out and make a show of himself while I crawl into the logs. Then he’d drive away and return for me after dark. My concern, do I have enough strength to dress the animal?

I’ll say to her, Mary, the season is ending. I won’t have to hike. I’ll lie down for a couple of hours. I’ll fire once. ‘The foreman will pick me up and help lift the animal. My heart is safer now than it’s been in years. Surely she’ll say that I am correct and to have a good time.

Returning to the hunt six weeks after heart surgery might seem a little soon to some people — to those who don’t hunt. But I’m a hunter and just thinking of future hunts and remembering past ones will continue to entertain and please me. There’s no knowing how many seasons remain, but Cody, thanks for the rest of my life.

Returning to the hunt six weeks after heart surgery might seem a little soon to some people — to those who don’t hunt. But I’m a hunter and just thinking of future hunts and remembering past ones will continue to entertain and please me. There’s no knowing how many seasons remain, but Cody, thanks for the rest of my life.

Addendum: The plot worked. The patient/hunter found adequate strength and deep satisfaction in cutting and wrapping his whitetail venison; not as much nor quite as good-tasting as elk, but simply wonderful, considering.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson. Buy Now