It was a cold, clear night in the little camp at the Grummetti in Tanganyika. A sharp, winy night, like New England in the fall, with the stars distinct against the sky. The boys had built a roaring blaze out of dead thornbush logs. The dinner was responding kindly to a third cup of coffee. Everybody was tired. It had been a big day. There had been the immense waterbuck in the morning and the red-headed lion in the afternoon, and the business with the lioness and the cubs.

Suddenly the wind veered. A smell swept down on the breeze, a dreadful smell.

“O-ho,” Harry Selby said. “Chanel No. 5, if you are a leopard. That delicious aroma would be your pig and your Grant gazelle. It may smell awful to you, but the bait has hit just about the right stage of decay to be better than Camembert to our noisy friend of the fig tree. I was never able to figure why the cleanest, neatest animal in the bush waits until his dinner is maggoty before he really works up an appetite. Let’s see. We’ve had the bait up five days now. The boys say your pussycat’s been feeding since yesterday. He ought to be through the pig now and working on the Grant. He ought to be feeling pretty cheeky about his vested interest in that tree.

“I don’t know what there is about the tree,” the professional hunter went on. “I think maybe it’s either bewitched or made out of pure catnip. You can’t keep the leopards out of it. It’s only about five hundred yards from camp. I come here year after year, and we always get a leopard. I got one three months ago. I got one six months before that. There’s an old tabby lives in it, and she changes boy friends every time. We’ll go to the blind tomorrow and we’ll pull her newest fiancé out for you – that is, if he’s eaten deep enough into that Grant. That is, if you can hit him.”

At this stage I was beginning to get something past arrogant. Insufferable might be the right word.

“What is all this mystery about leopards?” I asked. “Everybody gives you the old mysterious act. Don Ker tells me about the safari that’s been out fourteen years and hasn’t got a leopard yet. Everybody says you’ll probably get a lion and most of the other stuff, but don’t count on leopards. Leopards are where you find them. We got two eating out of one tree and another feeding on that other tree up the river, and we saw one coming back from the buffalo business yesterday. They run up and down the swamp all night, cursing at the baboons.

“You sit over there looking wise, and mutter about if we see him and if I hit him when we see him. You’ve been polishing up the shotgun and counting the buckshot ever since we hung the kill in the tree. What do you mean, if I hit him? You throw a lion at me the first day out, and I hit him in the back of the neck. I bust the buffalo, all right, and I get that waterbuck with one in the pump, and I knock the brain pan off that second Simba today okay enough, and I break the back on a running eland. What have I got to do to shoot a sitting leopard at thirty-five feet with a scope on the gun? Use a silver bullet?”

“Leopards ain’t like other things,” Harry said. “Leopards do strange things to people’s personality. Leopards and kudu affect people oddly. I saw a bloke fire into the air three times once, and then throw his gun at a standing kudu. I had a chap here one time who fired at the leopard first night, and missed. We came back the second night. Same leopard in the tree. Fired again. Missed. This was a chap with all manner of medals for sharpshooting. A firecracker. Splits lemons at three-hundred and fifty yards, shooting offhand. Pure hell on running Tommies at six hundred yards, or some such. Knew everything about bullet weights and velocities and things. Claims a .220 Swift is plenty big enough for the average elephant. Already had the boys calling him One-Bullet Joe.”

“So?” I inquired.

“Came back the third night. Leopard up the tree. Fired again. Broad daylight, too, not even six o’clock yet. Missed him clean. Missed him the next night. Missed him for the fifth time on the following night. Leopard very plucky. Seemed to be growing fond of the sportsman. Came back again on the sixth night, and this time my bloke creases him on the back of the neck. Leopard takes off into the bush. I grab the shotgun and take off after him. Hapana – nothing. No blood and no tracks. Worked him most of the night with a flashlight, expecting him on the back of my neck any minute. Hapana chui – no leopard. My sport quit leopards in disgust, and went back to shooting lemons at 350 yards.”

“How do you know the marksman touched him on the neck?” I asked sarcastically. “Did he write you a letter of complaint to Nairobi?”

“No,” Harry said gently. “I came back with another party after the rains, and here was this same chui up the same tree. This client couldn’t hit a running Tommy at six hundred yards, and he couldn’t see any future to lemon-splitting at 350. But his gun went off, possibly by accident, and the old boy tumbled out of the tree and when we turned him over there was a scar across the back of his neck, and still reasonably fresh. Nice tom, too. About eight foot, I surmise. Not as big as Harriet Maytag’s, though. He was just on eight-four.”

“If I hear any more about Harriet Maytag’s lion or Harriet Maytag’s rhino, Mr. Selby,” I declared with considerable dignity, “it will not be leopards we shoot tomorrow. It will be white hunters, and the wound will be in the back. Not the first time it’s happened out here, either. I’m going to bed possibly to pray that I will not embarrass you tomorrow. Evan if I am not Harriet Maytag, I still shoot a pretty good lion.”

There was an awful row down by the river. The baboons set up a fearful cursing, the monkeys screamed, and the birds awoke. There was a regular, painting, wheezing grunt in the background, like the sound made by a two-handed saw on green wood.

“That’s your boy, chum,” Selby said brightly. “Come to test your courage. If you find him in the tent with you later on, wake me.”

We went to bed. I dreamed all night of a faceless girl named Harriet Maytag whom I had not met and who kept changing into a leopard. I also kept shooting at lemons at three and a half feet, and I missed them every time. Then the lemons would turn into leopards, and the gun would jam.

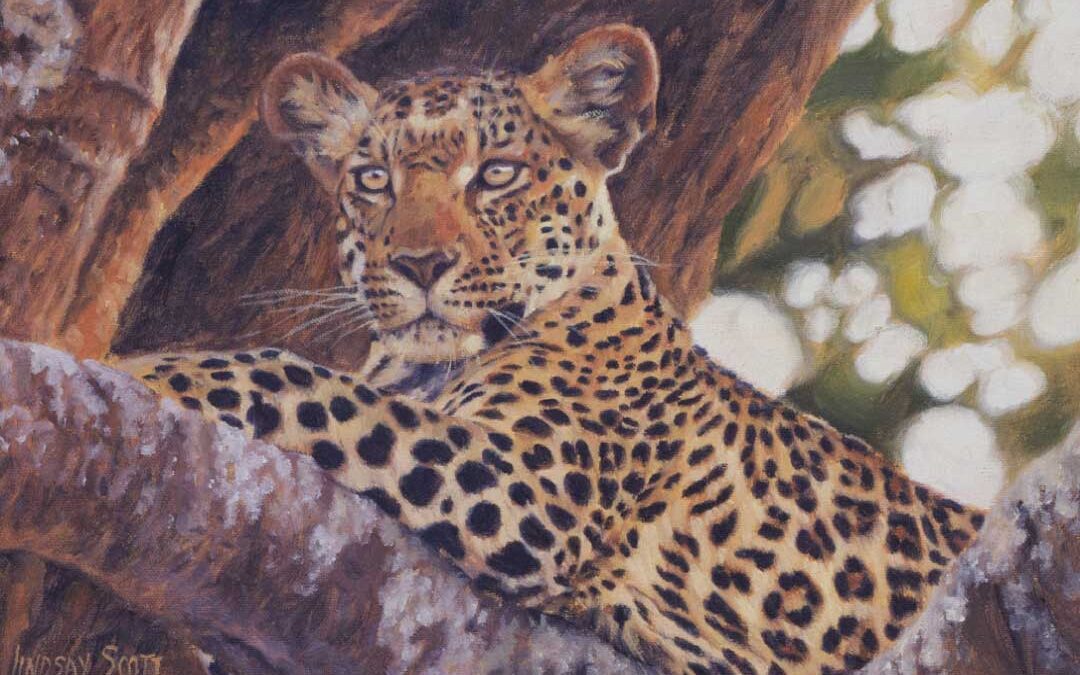

Leopard! by Linda Besse

Everybody I had met in the past six months had a leopard story for me. How you were extremely fortunate even to get a glimpse of one, let alone a shot. How they moved so fast that you couldn’t see them go from one place to another. How you only got one shot, and whoosh, the leopard was gone. How it was always night, or nearly night, when they came to the kill, and you were shooting in the bad light against the dark background on which the cat was barely perceptible. How if you wounded him you had to go after him in the black, thick thorn. How he never growled, like a lion, betraying his presence, but came like a streak from six feet or dropped quietly on your neck from a tree. How, if four guys went in, three always got scratched. And how the leopard’s fangs and claws were always septic because of his habit of feeding on carrion. How a great many professionals rate him over the elephant and buffalo as murderous game, largely because he kills for fun and without purpose. And how unfortunately most of what you heard was true.

I had recently talked with a doctor who has sewed up three hunters who had been clawed by the same cat within the last six months. A big leopard runs only 150 pounds or so, but I had seen a zebra foal, weighing at least two hundred pounds, thirty feet above ground and wedged into a crotch by a leopard, giving you some idea about the fantastic strength that is hidden by that lovely spotted golden hide. I reflected that there are any amount of documented stories about leopards coming into tents and even houses after dogs and sometimes people and breaking into fowl-pens and leaping out of trees at people on horseback.

“A really peculiar beast,” Harry had said when we jumped the big one coming back from the buffalo. “Here we find one in broad daylight right smack out in the open plain, when there are people who’ve lived here all their lives and have never seen one. Here is a purely nocturnal animal who rarely ever leaves the rocks or the river-edge, standing out in the middle of a short-grass plain like a bloody topi. They are supposed to be one of the shyest, spookiest animals alive, yet they’ll come into your camp and pinch a dog right out of the mess tent. They’ll walk through your dining room on some occasions, and spit in your eye. They’re supposed to have a great deal of cunning, yet I knew one that came back to the same kill six nights in a row, being shot over and missed every time. But they’re a great fascination for me, and for most people.

“The loveliest sight I’ve ever seen since I stared hunting was a leopard sleeping in a thorn tree in the late afternoon. The tree was black and yellow, the same color as the cat, and the late sun was coming in through the leaves, dappling the cat and the tree with a little extra gold. We weren’t after leopard at the time, already had one; so we just woke him up and watched him scamper. He went up the tree like a big lizard.”

I was getting to know quite a bit about my young friend Selby by this time. He was a professional hunter and lived by killing, or by procuring things for other people to shoot, but he hated use a gun worse than any man I ever met. He has the fresh face and candid eyes of a man who has lived all his life in the woods, and when he talks of animals his face lights up like a kid’s in a toy store. He had nearly killed us all, a day earlier, coming back from a big ngama – lion dance party – in the Waikoma village. There were some baby francolin in the trail, and he almost capsized the Land Rover trying to miss them. What he liked was to watch animals and learn more about them. He refused to allow anyone to shoot baboons. He hated even to shoot a hyena. The only things he loved to shoot were wild dogs, merely because he disapproved of the way they killed by running their prey in shifts, pulling it down finally, and eating it alive.

“You’re a poet, man,” I told him. “The next thing, you’ll be using the sonnet form to describe how old Katunga howls when his madness comes on in the moonlight nights.”

“It would make a nice poem at that,” Harry said. “But don’t spoof me about leopards in trees. Wait until you have seen a leopard in a tree before you rag me. It’s a sight unlike any other in the world.”

When we got up that next morning, the scent of the rotting pig and the rotting Grant was stronger than ever. Harry sniffed and ordered up Jessica, the Land Rover. We climbed in and drove down the riverbank, with the dew fresh on the grass and a brisk morning breeze rustling the scrub acacias. As we passed the leopard tree there was a scrutching sound and a rustle in the bush that was not made by the breeze. A brown eagle was sitting in the top of the tree.

We made a daily ritual of this trip, after we had hung the bait the first day, in order to get the cat accustomed to the passage of the jeep. We also made a swing back just around dusk to get him accustomed to the evening visit. Always we passed close aboard the blind, a semicircle of thorn and leaves with a peephole and a crotched stick for a gun rest. Its rear was open to the plain and its camouflaged front faced the tree. By now it would seem that the leopard had been feeding on the two carcasses we had derricked up to an L-shaped fork about 30 feet above ground and tied fast with rope.

You could just define the shape of the pig, strung a little higher than the Grant, as they hung conveniently from another limb, in easy reach of the feeding fork. The pig was nearly consumed now, his body and neck all but gone and his legs gnawed clean to the hairy fetlocks. The guts and about twenty pounds of hindquarter were gone from the Grant. The steady wind was blowing from the tree and toward the blind, and they smelled just lovely.

Harry didn’t say anything until he had swung Jessica around and we were driving back to the camp and breakfast. “You heard the old boy leave his tree, I suppose. I got a glimpse of him as we drove by. And did you notice the eagle?”

“I noticed the eagle,” I said. “How come eagles and leopards are so chummy?”

“Funny thing about a lot of animals,” Harry observed. “You know how the tick-birds work with the rhino. Rhino can’t see very much, and the tick-birds serve as his eyes, in return for which they get to eat his ticks. I always watch the birds when I’m stalking a rhino. When the birds jump, you know the old boy is about to come bearing down on you. Similarly, you’ll always find a flock of egrets perched on the backs of a buffalo herd. You can trace the progress of a buff through high grass just by watching the egrets.

“I don’t know how they work out their agreements,” Harry went on. “Often you’ll see a lion feeding on one end of a kill and a couple of jackals chewing away on the other. Yet a lion won’t tolerate a hyena or a vulture near his kill.

“Now, our friend, this leopard which you may or may not shoot tonight, or tomorrow night, or ever, has this transaction with the eagle. The eagle mounts guard all day over the leopard’s larder. If vultures or even another leopard comes by and takes a fancy to old Chui’s free lunch, the eagle sets up a hell of a clamor and old Chui comes bounding out of the swamp to protect his victuals. In return for this service the eagle is allowed to assess the carcass a pound or so per diem. It’s a very neat arrangement for both.”

We went back to camp and had the usual tea, canned fruit and crumbly toast. It was still cold enough for the remnants of last night’s fire to feel good.

“We won’t hunt today,” Selby said. “We’ll just go sight in the .30-06 again and you can get some writing done. I want you rested for our date with Chui at four o’clock. You’ll be shaking enough from excitement, and I don’t want it complicated with fatigue.”

“I will not be shaking from excitement or fatigue or anything else,” I declared. “I am well known around this camp as a man who is as icy calm as Dick Tracy when danger threatens. In nearby downtown Ikoma I’m a household word amongst the rate-payers. I am Old Bwana Risase Moja, slayer of Simba, Protector of the Poor, Scourge of the Buffalo, and the best damn bird shooter since Papa Hemingway was here last. I promise you, you will not have to into any bush after any wounded leopard this night. I’m even going to pick the rosette I want to shoot him through. I intend to pick one of the less regular patterns, because I not want to mar the hide.”

“Words,” Selby said. “Childish chatter from an ignorant man. Let’s go and sight in the .30-06. We’ll sight her pointblank for fifty yards. They make a tough target, these leopards. Lots of times you don’t have but a couple of inches of fur to shoot at. And that scope has got to be right.”

“How come the scope? I thought you were the original scope-hater. At thirty-five yards I figure I can hit even one of those lemons you’re always talking about with open sights, shooting from a forked stick.”

Harry was patient, as if talking to a child. “This is the only time I reckon a scope to be actually necessary out here. The chances are that when that cat comes it will be nearly dark, well past shooting light. You won’t even be able to see the kill with your naked eye, let alone the cat. The scope’s magnification will pick him out against the background, and you can see the post in the scope a lot easier than you could see a front sight a foot high through ordinary open sights. And if I were you, I’d wear those polaroid glasses you’re so proud of, too. Any visual help you can get you will need, chum.”

We sighted in the .30-06, aiming at the old blaze on the sighting-in tree. Then we trundled Jessica back to camp, pausing on the way long enough to shoot a Thomson gazelle for the pot. It was a fairly long shot, and I broke his neck.

“I think I can hit a leopard, I said.

“A lousy little Tommie is different thing from a leopard,” Harry replied. “Tommies have no claws, no fangs, and do not roost in trees.”

“We slopped around camp for the rest of the morning, reading detective stories and watching the vultures fight the marabou storks for what was left of the waterbuck carcass. Lunchtime came, and I made a motion toward the canvas water bag where the gin and vermouth lived.

“Hapana,” Harry said. “No booze for you, my lad. For me, yes. For Mamma, yes. For you, no. The steady hand, the clear eye. You may tend to bar if you like, but no cocktails for the Bwana until after the Bwana has performed this evening.”

“This could go on for days.” I grumbled. “Bloody leopard may never come to the tree.”

“Quite likely,” Harry remarked, admiring a small glass of lukewarm gin with some green lime nonsense in it. “The more for me and Mama. A lesson in sobriety for you.”

A bee, from the hive in the tree behind the mess tent, dive-bombed Harry’s glass and swam happily around in the gin-and-lime. Harry fished him out with a spoon and set him on the mess table. The bee staggered happily and buzzed blowsily.

“Regard the bee,” he said. “Drunk as a lord. Imagine what gin does to leopard shooters, whose glands are activated by fear and uncertainty.”

“Go to hell, the both of you. I’ll eat while these barflies consume my gin.”

The lunch was fine – yesterday’s cold boiled guineafowl flanked by some fresh tomatoes we had swindled out of the Indian storekeeper in Ikoma, with hot macaroni and cheese that Ali the cook produced from his biscuit-tin over and some pork and beans in case we lacked starch after the spaghetti, bread and potatoes. Harry allowed me a bottle of beer.

“Beer is a food,” he told me. “It is not a tipple. Now go take a nap. I want you fresh. I hate crawling after wounded leopards who have been annoyed by amateurs. It’s so lonesome in those bushes after dark, the leopard waiting ahead of you and the client apt to shoot you in the trousers the first time a monkey screams.”

I dozed a bit, and at four o’clock Harry came into the tent and roused me. “Leopard time,” He said. “Let’s hope he comes early. It’ll give the bugs less chance to devour us. Best smear some of that bug dope on your neck and wrists and face. And if I were you, I’d borrow one of the Memsahib’s scarves and tie it around most of my face and neck. If you have to sneeze, sneeze now. If you have to clear your throat or scratch or anything else, do it now, because for the next three hours you will sit motionless in that blind, moving no muscle, making no sound, and thinking as quietly as possible. Leopards are allergic to noise.”

I looked quite beautiful with one of Mama’s fancy Paris scarves, green to match the blind, tied around my head like an old peasant woman. We climbed into Jessica. Harry was sitting on her rail from the front-seat position. The sharp edge of her after-rail was cutting a chunk out of my rear. We went past the blind at about twenty miles an hour, and we both fell out, command-style, directly into the blind. The jeep took off, to return at the sound of a shot or at black dark if no shot.

I wriggled into the blind and immediately sat on a flock of safari ants that managed to wound me severely before we scuffed them out. I poked the .30-06 through the peep-hole in the front of the blind and found that it centered nicely on the kill in the tree. Even at four-thirty the bait was indistinct to the naked eye. The scope brought it out clearly. I looked over my shoulder at Selby, his shock of black hair uncluttered by shawl or insecticide. A tsetse was biting him on the forehead. He let it bite. My old 12-gauge double, loaded with buckshot, was resting over his crossed knees. He looked at me, shrugged, winked and pointed with his chin at the leopard tree.

We sat. Bugs came. Small animals came. No snakes came. No leopards came. I began to think of how much of my life I had spent waiting for something to happen – of how long you waited for an event to occur, and what a short time was consumed when the event you had been waiting for actually did come to pass. The worst thing about the war at sea was waiting. You waited all through the long black watches of the North Atlantic night, waiting for a submarine to show its periscope. You could not smoke. You did not even like to step inside the blacked-out wheelhouse for a smoke because the light spoiled your eyes for half an hour. You waited on islands in the Pacific. You waited for air raids to start in London, and then you waited some more for the all-clear. You waited in line at the training school for chow, and for pay, and for everything. You waited in train stations, and you sat around airports waiting for your feeble priority to activate – you waited everywhere. From the day you got into it until the day you got out of it you were waiting for the war itself to end, so that it was all one big wait.

Sitting in the blind, staring at the eaten pig and the partially eaten Grant and waiting for the leopard to come and hearing the sounds – the oohoo-oohoo-hoo of the doves and the squalls and squawks and growls and mutters in the dark bush ahead by Grummetti River – I thought profoundly that there was an awfully good analogy in waiting for a leopard by a strange river in a strange dark country. I began to get Selby’s point about the importance of a leopard in a tree – waited for, planned for, suffered for – to be seen for one swift moment or maybe not to be seen at all.

These are the thoughts you have in a leopard blind in Tanganyika when the ants bite you and you want to cough and you nose itches and nothing whatsoever can be done about it. Five o’clock came. No leopard. Hapana chui, my head said in Swahili. I looked at Selby. He was scowling ferociously at a flock of guineafowl that seemed to be feeding right into the blind. With his hand he made a swift, attention-getting gesture. The guineas got the idea, and marched off. Selby pointed his chin at the leopard tree and shrugged. Now it was six o’clock. I thought about the three weeks I sweated out in Guam, waiting for orders to leave that accursed paradise, orders I was almost sure of but not quite. When they came, they came in a hurry. They came in the morning and I left in the afternoon. Six-thirty. Hapana chui.

It was getting very dark now, so dark that you couldn’t see the kill in the tree at all without training the rifle on it and looking through the scope. Even then it was indistinct, a blur of Lodies against a green-black background of foliage. I looked at Selby. He rapidly undoubled both fists twice, which I took to mean 20 more minutes of shooting time.

My watch said 12 minutes to 7, and it was dead black in the background and the pig was nonvisible and the Grant only a blob and even where it was lightest it was dark gray. I thought, Damn it, this is the way it always is with everything. You wait and suffer and strive, and when it ends it’s all wasted, and the hell with all leopards.

Then I felt Harry’s hand on my gun arm. Down the river to the left the baboons had gone mad. The uproar lasted only a split second, and then a cold and absolute calm settled on the Grummetti. No bird. No monkey. No nothing. About a thousand yards away there was a surly, irritable cough. Harry’s hand closed on my arm, and then relaxed. My eyes were on the first fork of the big tree.

There was only tree to watch, a first fork full of nothing. Then there was a scrutching noise like the scrape of stiff khaki on brush, and where there had been nothing but tree there was now nothing but leopard. He stretched his lovely spotted neck and turned his big head arrogantly and slowly, and he seemed to be staring straight into my soul with the coldest eyes I have ever seen. The devil would have leopard’s eyes, yellow-green and hard and depthless as beryls. He stopped turning his head and looked at me. I had the post of the scope centered between those eyes. His head came out clearly against the black background of forest. It looked bigger than a lion’s head.

You are not supposed to shoot a leopard when he comes to the first fork. The target is bad in that light and small, and you either spoil his face if you hit him well or you wound him and there is the nasty business of going after him. You are supposed to wait for his second move, which will take him either to the kill or to a second branch, high up, as he makes a decision on eating or going up in the rigging. If he is not shot on that second branch or shot as he poises over the kill, he is not shot. Not at all. You can’t see him up high in the thick of foliage. And Harry had said, “On a given night there has never been more than one shot at a leopard.”

I held the aiming post of my telescopic sight on that leopard’s face for a million years. While I was holding it the Pharaohs built the pyramids. Rome fell. The Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock. The Japs attacked Pearl Harbor.

And then the leopard moved. Only you could not see him. Where there had been leopard there was only fork. There was not even a flash or a blur when he moved. He disappeared.

Then he appeared on a branch to the left of the kill, a branch that slanted upward into the foliage at a 45-degree angle. He stood at full pride on that branch, not crouching, but standing erect and profiling like a battle-horse on an ancient tapestry, gold and black against the black. There was a slightly ragged rosette on his left shoulder as he stood with his head high.

The black asparagus tip of the aiming post went to the ragged rosette, and a little inside voice said, Squeeze, don’t jerk, because Selby is looking and you only get one shot at a –

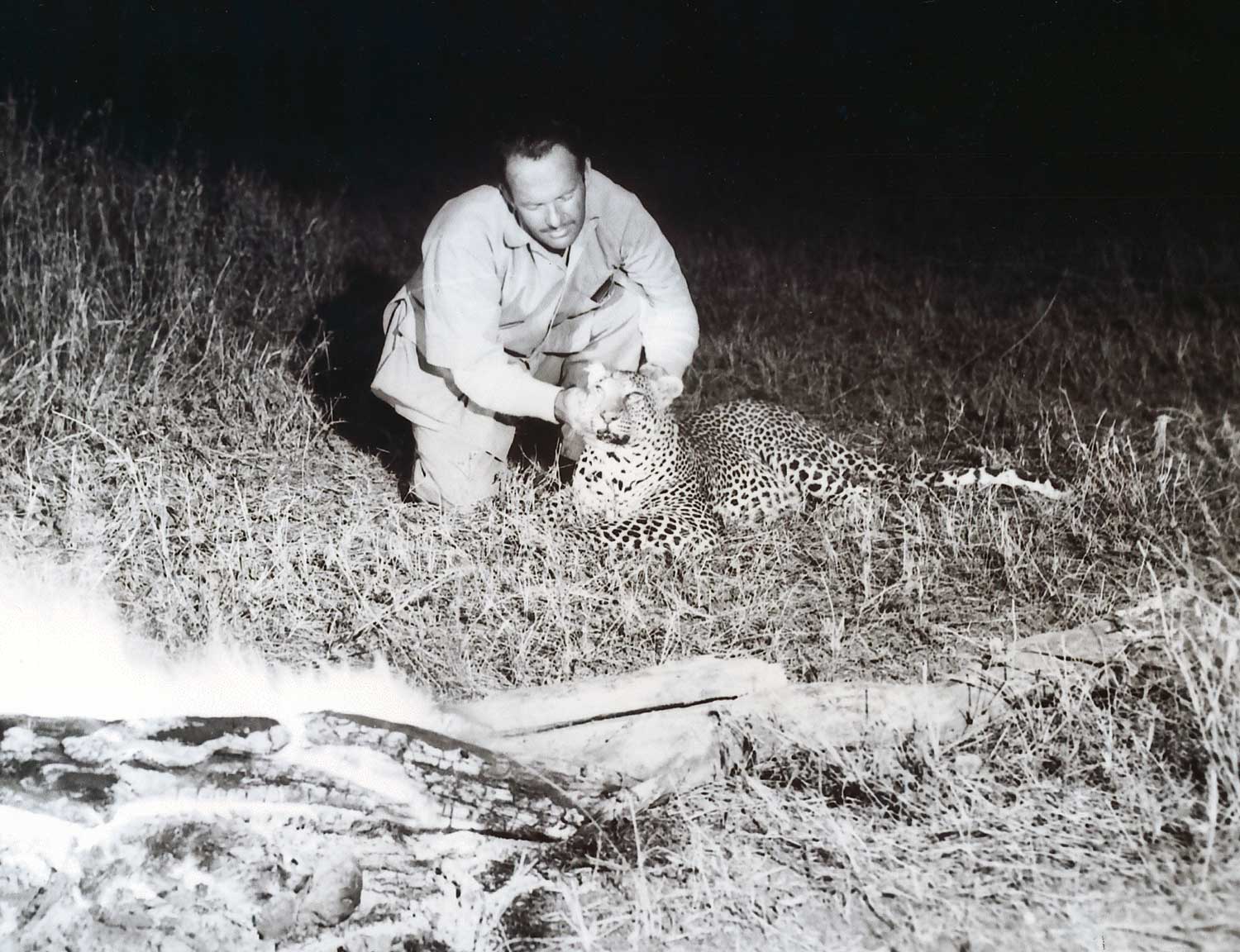

I never heard the rifle fire. All I heard was the bullet whunk. It was the prettiest sound I ever heard. No, not quite the prettiest. The prettiest was the second sound, which said blonk. That was the sound the leopard made when he hit the ground. It sounded like a bag of soft cement dropping off a roof. Blonk. No other sounds. No moans. No growls. No whish or swift, bounding feet on bush.

A hand hit me on the shoulder, bringing me back into the world of living people.

“Piga,” Harry said. “Kufa. As bloody kufa as a bloody doornail. Right on the button. He’s dead as a bloody beef in there. We were as near to losing him as damn to swearing, though. I thought he’d never leave that bloody fork and when he went I knew he was heading up to the crow’s nest. You shot him one-sixtieth of a second before he leaped, because I could just make out his start to crouch. You got both shoulders and the heart, I’d say, from the way he came down. Aren’t they something to see when they first hit that fork, with those bloody great eyes looking right down your throat and that dirty big head turning from side to side! You shot him very well, Bwana Two Lions. Did you aim for any particular rosette like you said?

“Go to hell twice,” I said. “Give me a cigarette.”

“I think you’ve earned one,” Harry said. “Then let’s go retrieve your boy. I’ll go in ahead with the shotty-gun. You cover me from the left. If he’s playing possum in there, shoot him, not me. If he comes, he’ll come quick, except I would stake my next month’s pay that this chui isn’t going anywhere. He’s had it.”

Harry picked up the old 12-guage and I slipped the scope off the .30-06 and slid another bullet into the magazine. We walked slowly into the high bush, Harry six steps ahead and I just off to the left. I knew the leopard was dead, but I knew also that dead leopards have carved chunks out of lots of faces. Selby was bobbling the shotgun up and down under his left shoulder, a mannerism he has when he wants to be very sure there is nothing on his jacket to clutter a fast raise and shoot. We needn’t have worried.

Chui – my chui now – was sleeping quietly underneath the branch from which he had fallen. He had never moved. He was never going to move. This great, wonderful golden cat, eight foot something of leopard, looking more beautiful in death than he had looked in the tree, this wonderful wide-eyed, green-yellow-eyed cat was mine. And I had shot him very well.

“You picked the right rosette,” Harry said. “Grab a hind leg and we’ll lug him out. He’s a real beauty. Isn’t it funny how most of the antelopes and the lions lose all their dignity in death, while this blighter is more beautiful when he’s in the bag than he is in the tree? Look at those eyes. No glaze at all. He’s clean as a whistle all over, and yet he lives on filth. He eats carrion and smells like a bloody primrose. Yet a lion is nearly always scabby and fly-ridden and full of old sores and cuts. He rumples when he dies, and seems to grow smaller. Not Chui, though. He’s the most beautiful trophy in Africa.”

“How does he compare with Harriet Maytag’s leopard?” I asked, rather caustically, I thought.

“Forget Harriet Maytag, chum,” Harry said. “I was only kidding. As far as I’m concerned, you are not only Bwana Simba, Protector of the Poor, but a right fine leopard man, too. Here come the boys. Prepare to have your hand shaken”

The boys ohed and ahed and gave me the old double-thumb grip, which means that the Bwana is going to distribute largesse later when he has quit bragging and the liquor has taken hold. We piled the big fellow into Jessica’s back seat and took off for camp. Mama nearly fainted when we took the leopard out of the back and draped him in front of the campfire. The wind had changed again and she had heard no shot. When the boys left in the dark with the Rover, she had assumed they were going to pick us up.

The leopard looked lovelier than ever in front of the campfire. His eyes were still clear. His hide was only gorgeous. Even the bullet hole was neat. He was eight feet and a bit, and he was a big tom. About one-fifty on an empty stomach.

“Tail’s a big too short for my taste thought,” Harry said. “Harriet’s had a longer tail.”

“Harriet be damned. After you’re through with the pictures, mix me a martini.”

Harry took the pictures. He mixed me a martini. I drank it and passed out – from sheer excitement, I suppose, because I hadn’t had a drink all day.

The next evening when Harry and Mama went down to see about the female, with cameras, she had already acquired another tom. This leads me to believe that women are fickle.

The tom came in across the plain, which leopards never do, and passed within a few feet of the blind. He growled mightily as he bounded past. The Memsahib gave up leopard photography. She said that Selby was obviously deaf, or he would have heard the leopard coming through the grass.

Originally published in Field & Stream, April 1953. Reprinted by permission of Harold Matson Co., Inc.