Jadu Manji tried desperately to keep the tattered umbrella over the head of his wife Rongo as she attempted to shield her two-month-old infant from the incessant rain. The little family huddled under the eaves of a small rural bus stop near the village of Dharampur in Orissa state. The thatch provided little protection as the rain dripped down on them. It was late December and the night was cool. The soaking rain made everyone shiver as they crowded together for warmth. No one else was at the stop, probably recognizing that travel on such a night had better be postponed until another day. The family had important business at Balliguda, and both the man and his wife hoped the bus would come soon. At least inside the bus it would be dry.

The rain turned into a drizzle as the evening progressed and Jadu Manji handed his wife the umbrella, saying he needed to make a quick stop behind the hut before the bus arrived. Rongo smiled and told him to come right back. There was no one around, and it was deathly quiet at the edge of the small village. Jadu Manji said he would only be a second and walked off into the darkness.

After several minutes Rongo called out, telling her husband to hurry. No answer came, and Rongo wondered why her husband had gone so far from the hut. She called again, louder this time, but still no reply came. By now Rongo was becoming a bit annoyed as she pulled her shawl tighter about her and the baby. After several more minutes she stood up and went to the corner of the hut and shouted into the pitch-black darkness, telling Jadu Manji to be quick since she could hear the bus coming as it slithered along the muddy road to the village.

Rongo approached the driver as the bus came to a halt, saying she and her husband were passengers but her husband had left and had not returned. Hearing what she had said, several of the passengers made rude jokes about her missing husband, and everyone laughed loudly when someone suggested that maybe he had gone off for a drink. Several inconsiderate passengers added that she should return to her village to locate her errant husband and not hold up their departure.

When the driver switched on his headlights, he could see a white, unidentified object lying on the track some 50 yards in front of the bus. Among the passengers was a man more knowledgeable than the rest who had been listening with growing concern to Rongo’s tale. He was a police officer and announcing his identity, he ordered the bus driver to pull up to the white object to see what it was. Soon everyone could clearly see in the headlights that the object was a piece of white garment called a chaddar. There was a marked hush among the passengers as the police officer retrieved the item, and all could clearly see that it was brightly stained with blotches of blood. Calling Rongo to his side, he showed her the grisly discovery. She quickly identified it as the chaddar which her husband had been wearing when he disappeared. There was no longer any question as to what had happened and several passengers came out to console Rongo who was screaming loudly in anguish and fear. It was a fear that gripped everyone, and the police officer commanded all the passengers back into the bus for safety.

Without a further word being said, everyone knew immediately that Jadu Manji had fallen victim to either a tiger or leopard and had been carried away in the darkness. There had been no sound. No cry for help. Death had been swiftly and skillfully executed. Knowing there was little further that could be accomplished, the police officer ordered the bus driver to proceed to the next station at Nuagam Post Office, taking the distraught wife and child along with them.

I was staying at a small bungalow at Nuagam at the time, and seeing the bus approach shortly after breakfast, I stepped off my verandah to see if my mail had been brought for me. It was still cold and wet outside, and I carefully sidestepped or jumped over the many puddles of rainwater still on the road as I approached the bus. A crowd of people had gathered, and as they saw me, a group split off running toward me. Everyone was shouting at once and I could make no sense of what they were saying. The police officer gave an authoritative command of silence and the group quickly shut up. Stepping forward, pulling the hysterical Rongo and her child with him, he proceeded to tell me what had happened at Dharampur the preceding night. Although no one was absolutely certain, everyone strongly suspected that a man-eater had carried off the missing man.

Questioning the crying woman was unproductive as all she could say was that Jadu Manji had walked off into the night, saying he would be right back and had never returned. She had heard or seen nothing until they had discovered his bloody piece of clothing. Placing Rongo in the care of some relatives, I made immediate arrangements to return to the scene to see what I could discover regarding the mysterious disappearance.

Later that morning, upon the return of the mail bus, my tracker Budiya and I, accompanied by the headman of Nuagam, returned to Dharampur, which we reached within a half-hour. In the bright sunshine after the night’s rain, the situation did not look nearly as ominous as it had in the dark of the night before. We started searching the sides of the road where the bloodstained garment had been found.

Within a few minutes we located the pugmarks of a large leopard in the muddy earth along the drain of the road embankment. We followed the tracks until we could see where the leopard had dug in when launching itself upon its victim. Having made the kill, the leopard had dragged Jadu Manji along the side of the road. While being carried off, the bloody outer garment had fallen off the man’s body.

We were joined by a number of other village men eager to help find the body. The clearly visible drag mark, which soon diverged from the road bank, went up a small, wooded hill. Next to a large boulder that had provided some shelter, the leopard had laid down the body and commenced to eat. The grisly remains shocked many of the villagers, who had never before seen a human kill made by a leopard. The man-eater had torn into the stomach cavity and had eaten a large portion of the lower abdomen as well as parts of the rib cage and a portion of the breast.

We examined Jadu Manji’s skull, which quickly explained why there had been no outcry during the attack. Four large punctures on the back of the head, which had penetrated the cranium, indicated that the killer had struck his victim from behind and, with one vicious bite, had killed him. Thankfully, he died an instantaneous death and probably never knew what had befallen him.

I had planned to sit up over the corpse in the event the man-eater returned to consume what was left of his kill. However, shortly the police officials from Balliguda arrived at the scene, guided by villagers. Since officialdom had preference, they removed the body, preventing any possibility of shooting the man-eater, even if he had returned. Unable to alter the situation, I returned to Nuagam village as well.

Several days went by with no further reported kills by the man-eater. It was during this time that two young men from Bodali village had gone off on a drinking party and were returning home from the Balliguda market. Since alcohol tends to exaggerate bravery as well as to dull common sense and good judgment, the two headed for home, despite full knowledge of the man-eater being in the area.

Upon reaching the banks of the Kalepin River, one of the drinking duet decided he was unable to proceed farther and said he would lie down for a nap. Unable to carry his companion, the older of the two decided to go on alone and planned to send someone back for his inebriated drinking partner as soon as he reached the village.

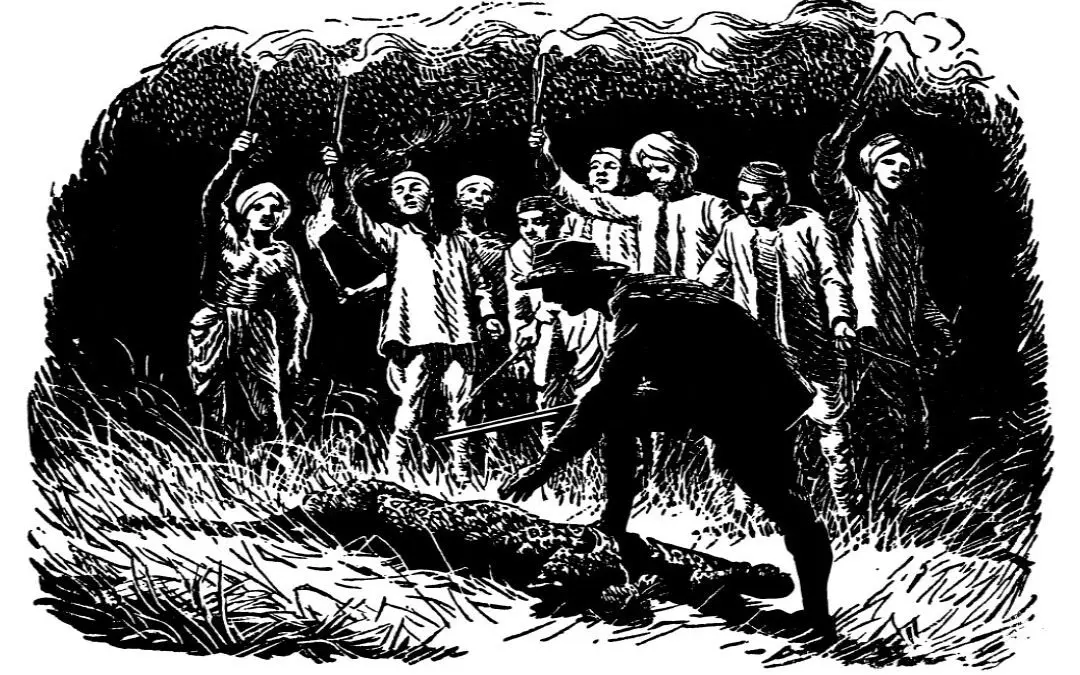

Upon reaching his home and explaining what had happened, the drunk was chastised for being out alone when he might well have become a victim of the man-eater. Several men soon left for the Kalepin River to bring the other man back to the village. They carried axes and flaming torches to protect themselves and light their way in the dark jungle.

Arriving at the spot on the riverbank that had been identified to them, they searched and called but could find no one. In the light of the torches someone soon saw a glint of reflection from an axe next to an empty liquor bottle. No one said it out loud, but the realization of what might have happened entered several heads simultaneously. Spreading out, one of the men came across a blood-soaked dhoti, which had belonged to the missing man.

No further examination was required for the entire group to realize that the man-eater had claimed another victim.

Knowing they could do nothing further to help, the two men ran as fast as possible to the village to alert everyone and make their gruesome discovery known. A larger group now quickly formed to return to the area to locate the body.

On the riverbank, the tracks of a leopard were soon found. Lying nearby was a small, tin mirror case, which was quickly identified as belonging to the missing man. Knowing that they could do little more in the dark and knowing the danger they themselves were in, the group returned to the village with the intention of resuming the search as soon as it was light enough to see.

I was still sound asleep that morning, unaware of what had happened at Bodali village. A messenger pounded on my door, awakening me, and breathlessly informed me of what had happened to the drunken reveler the night before. Quickly dressing, I asked the messenger who was accompanied by some Bodali village men to return to the place of the kill, adding that I would join them as soon as I could get my gear together.

I had a bicycle for transportation and was shortly at the place where the road crossed the river. The men escorted me to where the mirror case and the dhoti cloth had been found.

Strangely, we found tracks of both a tiger and a leopard, which momentarily confused the search. Soon, however, I located the place where the death struggle had occurred. A large stain of blood still was visible and the tracks of the leopard were without question those of the killer. The tiger had only been an innocent traveler through the area, either before or soon after the attack.

The question remained: Were these the tracks of the same leopard as the one that had killed Jadu Manji at the bus stop a few days before? It seemed likely that they were, since I’d never heard of two man-eaters operating in the same place at the same time.

While I contemplated the scene of the attack, a langur started calling from the nearby hillside. Some of the village men went to investigate and soon I heard shouts of “Come quickly, Sahib!” Rushing to the site, we pushed through the circle of men who were staring at what little was left of the unfortunate man. As in the other killing, the man-eater had eaten part of the stomach, chest and viscera.

There was much flesh still remaining on the body, so the village headman and I decided to sit up over the kill, hoping that the man-eater would return. We sent my tracker and the men from the village back to the road to wait for us, saying we would only stay until sundown. I told them to make noise on leaving so the leopard would think the entire group had departed.

We selected a comfortable spot at the base of a large thorn bush some 40 yards up the hill from the body. We had a clear field of vision, and I felt the thorn bush would give us reasonable protection from an unwanted attack from the rear.

We only intended to stay as long as there was sufficient light to shoot since I had not brought a flashlight and also did not relish a nighttime sit-up on the ground with the man-eater about.

About a half-hour before sundown we began to hear clearly audible noises coming from our left, quickly closing the distance between us. We were amazed the man-eater would be so reckless as to approach in this manner, apparently taking no precaution whatsoever. I had never before experienced such an audacious killer as this and gripped my rifle, knowing that in a moment the killer would reach the dead man’s body. Its approach grew louder and louder.

Anytime a man-eater comes to a kill, it is always a moment of extreme tension and excitement. Every nerve in my body was taut. Every sense was alert. Then the large, dark body of an animal came into view, making directly for the kill. I slowly placed the gun to my shoulder. My adrenaline rapidly drained as I looked at a wild pig rather than the leopard!

Knowing that the villagers would have never accepted the abhorrent possibility of a pig desecrating the dead body, I had no choice but to kill the animal, which fell dead at my shot.

Within moments I heard the excited shouting of my tracker and the villagers as they scurried up the hill, anticipating the death of the man-eater. I knew they would be disappointed but the circumstances were such that there was no other alternative. It was a quiet and dejected group that returned to the village that night, carrying with it the remains of the latest victim for proper burial.

On January 11 I was called from my home late in the afternoon by a villager on a bicycle imploring me to quickly follow him to the burial ground near Nuagam. He had been on his way to town and had seen a leopard brazenly exhuming a body in broad daylight. He insisted that if we hurried we might still find him there. I found all this a bit hard to believe but quickly slung my rifle over my shoulder, and we pedaled as fast as we could to the place where he had seen the leopard.

We parked the bicycles and quietly approached the burial site concealed by a small hedge. Peering cautiously over the top, I was amazed to see the leopard still pawing the ground not more than 50 yards away. I sighted over the hedge and fired a shot. The leopard spun about and made one gigantic leap and was gone.

Hearing the shot, several men joined us. Although we searched diligently, it soon became too

dark to see and we did not find the leopard.

Returning the next morning, we resumed the search again, going a bit farther into the bush, looking hopefully for blood spoor which, until then, had eluded us. With no signs to guide us, we were amazed when, quite by accident, we stumbled across the body of the leopard. Regretfully, it had been found by a hyena, which had managed to gnaw on the body and had consumed quite a bit of it.

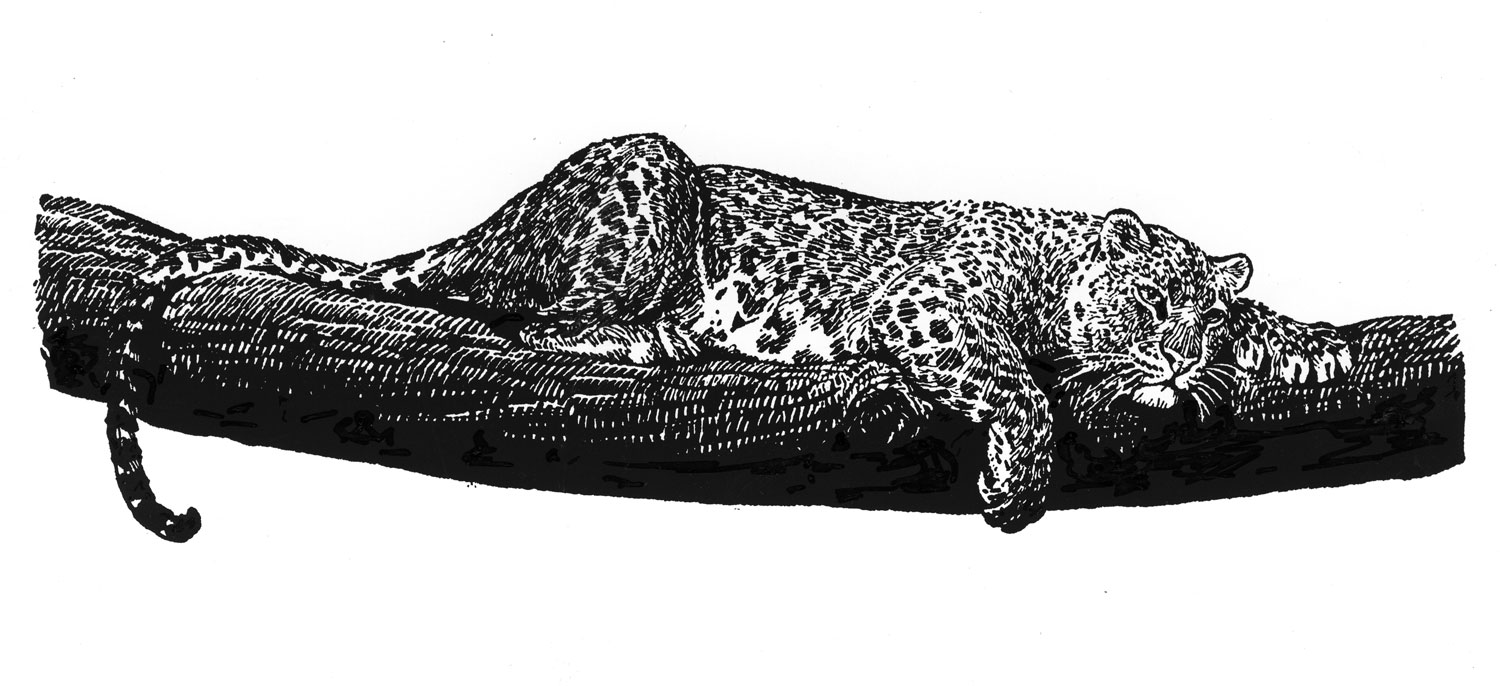

Although this was disappointing, the highlight of the discovery was that the leopard, which was a big male, had a large number of festering porcupine quills deeply imbedded in its left forefoot. The quills must have caused the animal great pain and would certainly have handicapped it in pursuit of normal prey. This, coupled with the fact that the leopard had been attempting to exhume a human body, left little doubt that this was the man-eater.

So much for optimistic and hasty conclusions that would soon almost cost us our lives.

January 12 dawned as another gloomy, rainy day, but since we felt we now had effectively taken care of the man-eater problem, I was pleased when the midday bus brought in a visitor to break the monotony of a long, lonely day. The man coming to my bungalow proved to be the schoolmaster from a larger village called Gunjibada, which lies about five miles up the road from Dharampur.

The man, Surja Singh, informed me that a tiger had killed a milk cow belonging to an elderly widow living in a tiny forest hamlet called Sandrekia. He had been asked by the people of the village to see if he could request my help in killing the animal. Listening to the description, I felt that the matter of shooting a cattle-killing tiger would be quite routine and, not having any other commitments, I told him I would be pleased to help.

I borrowed a 12-gauge shotgun and some heavy L.G. shells and, accompanied by my tracker Budiya, we caught the midday bus to Dharampur. After leaving the bus and before beginning our walk to the hamlet, I started to organize my gear and discovered that my 5-cell flashlight, upon which I was entirely dependent for nighttime shooting, had been left on the bus accidentally. There was little we could do except continue our walk toward Sandrekia, although I felt that now the situation totally favored the tiger rather than us.

I had with me a rustic lantern with a headlight reflector that had been left behind by American troops serving in India during the war. It was far from adequate, but under the circumstances, the best we had available. Budiya and I decided to give it a try, although we were not very optimistic.

Following Surja Singh’s directions, we walked along a swiftly flowing mountain stream, and soon after a strenuous climb reached the tiny hamlet, which consisted of all of three huts. Sandrekia was certainly no metropolis, but because of its size, it didn’t take long to find where the cow had been pulled down. The kill, we were told, was lying under a small hut located on a hillside a short distanced from the village.

A frail woman holding a small infant to her bosom volunteered to show us to the place, and then added that she was the owner of the dead cow. She was visibly moved as she told us that this was the last animal of three that she had owned and now she would be thrown upon the mercy of relatives to support her, since the tiger had now killed her last surviving animal.

The structure where the cow had been killed was a corral made of sturdy planks buried upright in the ground as a wall. On top of this was a bamboo frame covered with grass, which served as a roof. I examined the dead cow and the surroundings and quickly determined that the killer was a leopard rather than a tiger.

The woman begged me to rid them of the killer and stressed that it made little difference to her if the cow had died on the fangs of a leopard or a tiger. Knowing the desperate situation that existed at Sandrekia, I agreed to do what I could to shoot the beast.

Urging the villagers to return to their homes down the hill, Budiya and I dragged the cow outside of the enclosure; we then decided that in the absence of a suitable tree, we would start our vigil on the fragile roof of the cow pen. This gave us little security, since it was only about five feet high, but it was the best we could arrange. We placed a blind of straw in front of us to partially shield our movements and give me a chance to get my rifle in shooting position should the leopard return.

It soon turned cold as the sun went down, and we pulled our jacket collars up to protect us from the breeze that now blew with considerable force down the hillside.

All was quiet and we heard no sounds for the first two hours after sundown. Quite suddenly our tranquility was shattered by a violent push from underneath the bamboo roofing upon which we were seated. The unexpected jolt was a surprise we hadn’t expected and since we had heard or seen nothing, we moved our position a bit to see if we could peer into the cow pen to see what had happened, somehow knocking loose a board that fell from the roof into the interior of the pen.

A blood-curdling roar, followed by a deep snarl immediately below us, brought instant realization that the leopard had managed to sneak into the enclosure without alerting us and had tried, unsuccessfully, to reach us through the roof. It was a most unpleasant situation to be in, but it was quickly brought to resolution when the leopard made a bound over the outer wall of the corral and disappeared.

Budiya and I decided that our vantage point wasn’t the safest place to sit in the dark since the leopard now knew our position and might make a more successful stalk the next time if he should try again. We took our headlamp and, walking very cautiously through the darkness, proceeded to a small hut nearby, thinking that perhaps it would offer more security for us than the first. Reaching the hut, we went inside and Budiuya lit a small fire. We found, to our dismay, that the door to the hut could not be properly closed and that only a fragile stick was propped against it to keep it from swinging open.

Budiya, who had been quite shaken by our recent visitor, commented that in view of the animal’s aggressive behavior, he fully believed it was the man-killer, and that the leopard we had shot a few days earlier with the porcupine quills in its foot had not been the man-eater after all. I was inclined to agree since our recent visitor was abnormally unafraid of people and seemed determined to add a new victim to its list.

While discussing this possibility, we heard a soft movement against the door. It sounded almost like someone knocking to request permission to enter. For a moment we thought perhaps some hillmen, having seen us, were seeking shelter for the night.

I flashed on my headlamp and directed the beam toward the door. It suddenly became obvious that something was trying to enter and that the tapping was caused by the door being pushed inward against the small stick we had propped against it. We both came to the chilling realization that our visitor was the leopard trying again to reach us!

Being unsuccessful in opening the door, the leopard moved around the hut, examining it for other means of entry. We listened carefully, and I motioned Budiya to pick up a large boulder in the corner of the hut, which had been used for a fireplace, and place it securely against the door.

Budiya and I sat in complete silence, attempting to interpret sounds from outside as to what the leopard was doing. Our reverie came to a quick end as we heard the leopard jump onto the roof of the hut. Quickly this was followed by dust showering down on us accompanied by scratching and tearing sounds as the leopard attempted to make a hole through which he could enter the hut. There was now no longer any question that this was the man-eater!

The leopard, as if contemplating his next move, paused for a moment, and I took this opportunity to switch on the light, thinking that his attack had progressed to the point that the light would in no way deter the leopard from his intended purpose of killing us. Through the roof I could see the extended paw of the killer as he tried to enlarge the hole in the thatch.

Budiya gave a yell and the leopard, momentarily startled, withdrew his paw and stuck his head through the opening to survey the situation and, perhaps look over his intended meal.

The leopard was only a few feet above my head, and I could have touched him with the barrel tip. Before this unsurpassed opportunity to kill the man-eater could fade, I pulled the trigger at point blank range. The leopard slumped backward from the velocity of the shot, but did not fall off the roof. There was no sound and we felt sure he was dead.

Walking carefully outside we could see the spotted form lying on the roof of the hut. The shotgun blast, directly in his face, had been more than the man-eater could take.

Early the next morning some village men helped carry the leopard back to Nuagam. There was jubilation in Sandrekia and Dharampur and everyone felt they could now resume a normal way of life again without the constant fear of an imminent and horrible death.

While skinning this man-eater, I found that he also had been partially handicapped by having a number of porcupine quills imbedded in his forepaws. Walking must have been indeed painful for him. However, the decisive factor as to why he had turned into a man-eater was an old gunshot wound in his right shoulder. It had obviously crippled him to the point that he could no longer hunt properly and had turned to humans as his easiest source of food. There was no doubt that he was the dreaded man-eater and no more human deaths were reported in the area.

To my chagrin, I found that since I had not killed the leopard actively over a human kill, under existing law I could not claim the government reward. The gratitude of the village was, however, more than adequate compensation.

Note: “Leopard on the Rooftop” is from Hunters of Man (1989) by Capt. John H. Brandt. Reprinted by permission of Safari Press, Huntington Beach, California.