I felt terrible. I could have prevented the whole thing if only I had killed the leopard when it charged.

When our family of five set out on our hunting safari in Africa, we were prepared for a great adventure. Although we knew Africa could be a dangerous place, we weren’t too apprehensive because we felt secure in the hands of our two professional hunter guides. Besides, Mom, Dad and I had been on safari before, and we thought we knew what was in store for us.

We had come to Botswana to experience some of the last truly wild regions of Africa, and to hunt leopard, a prize that eluded us on our earlier safari. Mom, my 23-year-old sister Jennifer and 19-year-old brother Reese were here to witness the spectacle of beautiful landscapes, wild animals and the excitement of the chase. Dad and I would do the hunting, while the rest of the family observed from a safe distance. At least that was the plan.

We had come to Botswana to experience some of the last truly wild regions of Africa, and to hunt leopard, a prize that eluded us on our earlier safari. Mom, my 23-year-old sister Jennifer and 19-year-old brother Reese were here to witness the spectacle of beautiful landscapes, wild animals and the excitement of the chase. Dad and I would do the hunting, while the rest of the family observed from a safe distance. At least that was the plan.

The Kalahari Desert is one of the least hospitable places on earth. The vast bush country is not typical desert — there are plenty of trees and hiding places — but no permanent water. The numerous dry lake beds, or pans, contain water only during the rainy season, so the hardy carnivores of the desert rely on the fluids of their prey to survive. It is a difficult life, and the leopards that live there are unusually aggressive. We had been told that Kalahari leopards sometimes charge the hunter — a thrill that shouldn’t be missed.

The Kalahari is also unique because it’s one of the only places in Africa where leopards can be tracked on foot. The typical method is to place a bait high in a tree, then wait silently in a blind, sometimes for hours, hoping a leopard will appear. But the sandy soil and sparse undergrowth in the Kalahari makes tracking possible, which appealed to us because it promised an active hunt. The trackers were native bushmen who could trail a leopard for hours, without food or water, never losing their way in the wilderness.

Our plan was to set out in different directions each day. Dad’s professional hunter was Jeff Rann, an American who learned to hunt in Africa as a boy. Jeff has hunted in Botswana extensively and is one of the best in the business. My PH, Peter Hepburn, has lived in Africa all his life, and his understated manner and British accent evoke memories of those great hunters of the past. We had hired Chip Payne, a videographer already stationed in Botswana, to film our safari. But when we arrived in camp after two long days of travel, we learned that Chip had recently broken his hand and that his cast made it impossible for him to operate his camera. It appeared that our memories of the trip would not be captured on film.

We had barely settled into camp the first evening when Jeff and Dad found a fresh leopard kill. Since it was nearly dusk, we decided to return early the next morning, hoping to pick up a fresh track. Since we had only one leopard tag between us, I decided to join Dad on the leopard hunt. Even though I wouldn’t be stalking the animal myself, I didn’t want to miss out on the excitement. After an anxious night’s sleep, our entire entourage set off in the Land Cruisers on a crisp, cloudless, winter morning.

Less than an hour into the hunt, the haunting eyes of a half-eaten springbok peered at us from the fork of a tree some 20 feet off the ground. Leopard kills are almost always found high up in trees, hidden from marauding hyenas and the ever-present vultures. We felt lucky. This leopard had returned to feed during the night. Hopefully, with a full belly, it had not gone far. Though leopards like to find a shady place to rest during the heat of the day, we knew the cat would sense our presence long before we saw it and would be on the move. A leopard’s stamina is not great, so if pressed hard enough, we should eventually overtake him.

The morning gave way to afternoon and the desert air grew hot. I removed my hunting jacket, exposing bare arms. Though I didn’t pay attention at the time, Reese did not remove his jacket. Our Land Cruiser was open in the back, and Reese and I sat on a bench behind the cab, surrounded by a steel roll bar. Chip and two of the trackers kept us company. My rifle, a pre-1964 Model 70, was secured by bungee cords on the gun rack in front of us, its scope covered to protect it from the thick Kalahari dust. I did not plan on firing my rifle that day, but as a precaution, I kept it fully loaded with four bullets, one in the chamber.

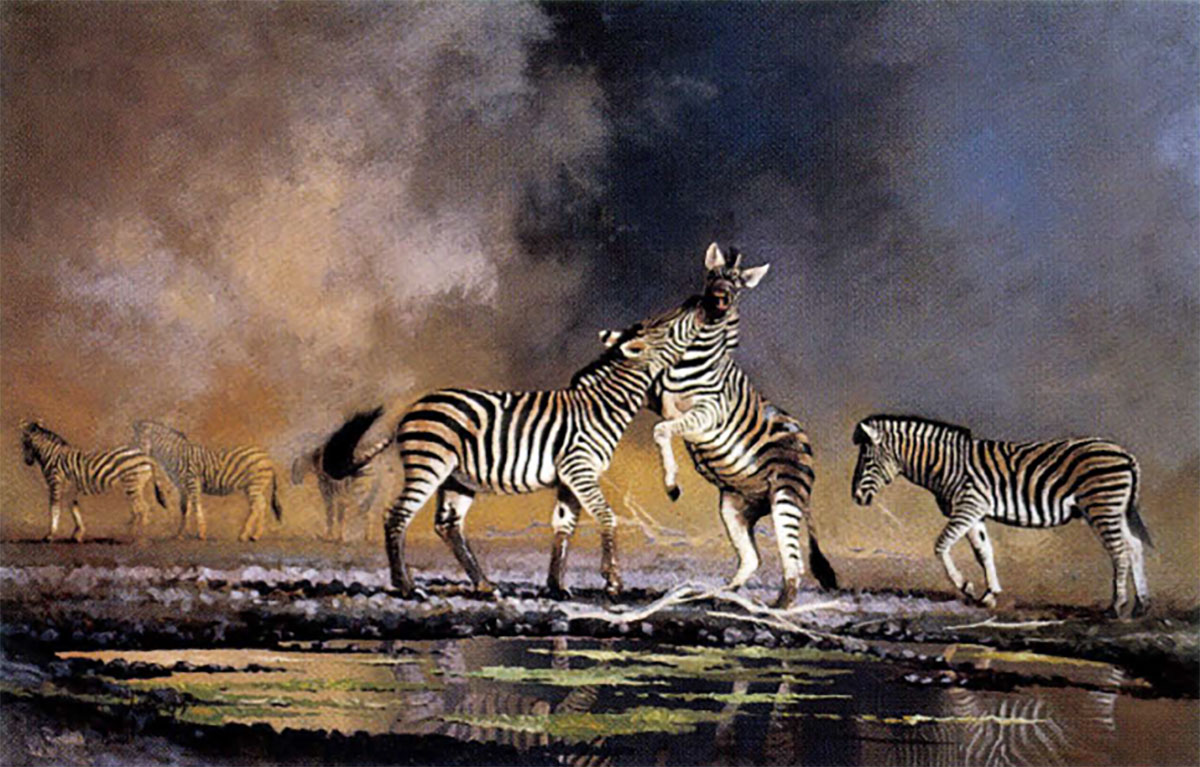

As the day wore on, I marveled at the beauty and abundance of wildlife in this parched land. Small herds of kudu, hartebeest and gemsbok were common. Occasionally little bat-eared foxes, always traveling in pairs, would flee at the sound of our vehicles, their large ears giving away their identity even from a distance. We stumbled upon an African wild cat, no larger than a house tabby and similar in appearance – an odd sight so far from civilization. We had no time for photographs, though, stopping only when the trackers needed to confer about the leopard’s direction.

Finally, in the middle of the afternoon the trackers got excited. The distance between the pug marks revealed the leopard was running — it was close. I immediately felt my throat go dry and my stomach turn. Reese and I looked at each other and smiled, anticipating the excitement that was about to begin. Jeff ordered the trackers onto the trucks so we could move quickly. We couldn’t afford to let the leopard increase the distance between us.

Hearing a commotion from the trackers, I saw a blurred form dart between bushes off to our right about a hundred yards. The drivers veered in that direction and we reached a spot where we thought the animal had gone. It seemed to have vanished. Then, without warning, the leopard appeared only 20 yards from our truck. Had I been the shooter, I could have taken it at that moment, but this was Dad’s trophy and I wasn’t about to spoil his hunt. Besides, shooting from a vehicle is hardly sporting.

Hearing a commotion from the trackers, I saw a blurred form dart between bushes off to our right about a hundred yards. The drivers veered in that direction and we reached a spot where we thought the animal had gone. It seemed to have vanished. Then, without warning, the leopard appeared only 20 yards from our truck. Had I been the shooter, I could have taken it at that moment, but this was Dad’s trophy and I wasn’t about to spoil his hunt. Besides, shooting from a vehicle is hardly sporting.

Jeff ordered my driver to stay put, so he and Dad could pursue the leopard on foot. Recognizing that too many people in close proximity to a dangerous animal presented an unreasonable risk, Mom and Jennifer were ushered into the cab of our truck. Reese and I remained in the back with Chip and two of the trackers. Peter, meanwhile, volunteered to accompany Jeff and Dad and to operate the video camera. We were determined to get this hunt on film, with or without Chip. I was the only one in our truck with experience in handling a rifle.

Dad and Jeff angled away from us in the direction the trackers thought the leopard had gone. Suddenly, I noticed movement in the bushes to my right and I heard Chip’s startled cry, “The leopard’s charging! You’re gonna have to shoot him!”

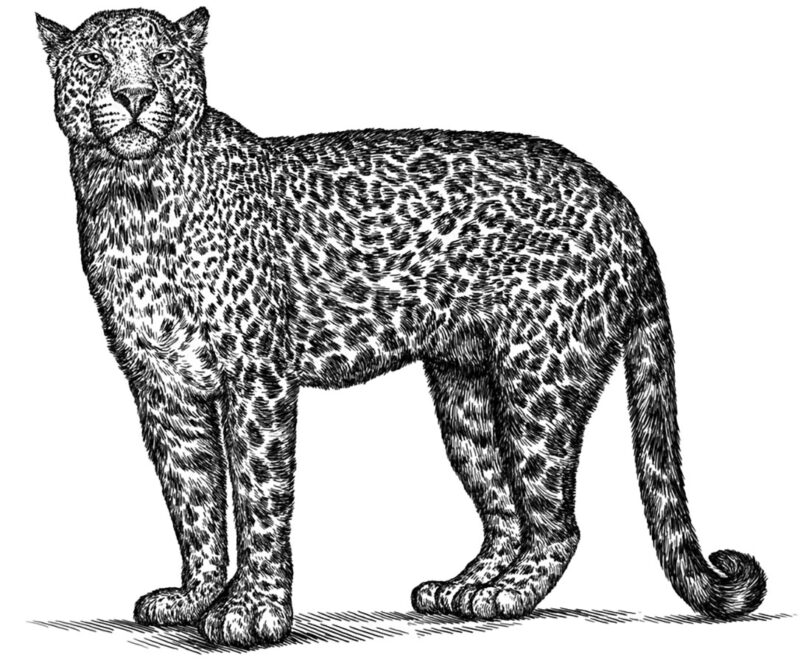

This couldn’t be happening, I thought. The trackers are never wrong, and they were following the leopard in the opposite direction. I tried to discern reality from reason, but sure enough, the leopard was bolting straight for us less than 50 yards away. The determined yellow eyes seemed as big as saucers and they were fixed directly on me! Surely this leopard, angry as it was, would not challenge a truck full of people. Yet here it came, without breaking stride, and I knew that I had better do something — fast.

I grabbed my rifle out of the rack, ripped off the scope cover and raised the gun to my shoulder. I peered through the scope to find the leopard, which by this time had closed to within ten yards, but saw nothing. The scope, set to magnify an object by seven times, was totally useless on a moving target at such close range. An open sight would have allowed me to fix on the animal. Instead, with the scope in the way, I could not tell where it was. At the last moment, I held the rifle away from my body and opened both eyes as if firing a shotgun. The leopard was charging right at me, only a split-second away from springing onto the truck. I fired, but nothing happened. I thought I had missed.

In an instant the leopard was upon me. It jumped over the roll bar and onto the bench that I had occupied moments earlier. I was now standing along the side of the truck, and Reese huddled under the bench, desperately trying to stay away from danger. I glimpsed one of the trackers vaulting over the cab and onto the hood. At that moment I was alone, facing 200 pounds of terror bent on making me pay for invading its turf.

I had no opportunity to eject the spent shell or to chamber another round. The rifle was the only thing keeping the leopard from tearing me to pieces, so I thrust the barrel forward and watched it enter the leopard’s mouth. Had there been a cartridge in the chamber, it would have been all over. But with one swipe of its big paw, the leopard sent my rifle flying toward the back of the truck.

Now totally defenseless and with only inches separating us, I instinctively barrel-rolled off the side of the truck, right over Reese, and onto the ground. In one motion, I scurried underneath the vehicle, arms draped over my head.

I was praying that the leopard would leap off the truck and scamper away into the bush. Instead, it ran smack into Reese, who had nowhere to go. The big cat pounced, sinking its teeth deep into Reese’s arm, while trying to grab his neck with both paws so it could disembowel him with its hind claws, as is the leopard’s custom. Mom and Jennifer watched helplessly, horrorstricken, through the rear window.

For what seemed like an eternity, I lay underneath the truck, blind to what was happening to my brother, hoping only that Dad and Jeff had heard the commotion and could reach us in time. I heard noises, but they were muted underneath the truck. Mercifully, I finally heard the gunshot I had been waiting for. Then, after a short silence, another shot. Still, I had no idea what was happening and remained motionless.

For what seemed like an eternity, I lay underneath the truck, blind to what was happening to my brother, hoping only that Dad and Jeff had heard the commotion and could reach us in time. I heard noises, but they were muted underneath the truck. Mercifully, I finally heard the gunshot I had been waiting for. Then, after a short silence, another shot. Still, I had no idea what was happening and remained motionless.

Suddenly, I was confronted by a new threat as dangerous as the leopard. Our driver had started the engine. “Oh my God,” I thought, as I stared at the rear axle, inches from my face. “I just survived a leopard attack, but now I’m about to be decapitated by the truck!”

I sensed that the driver was going to pull forward, but there was no time to roll out from underneath. I was trapped. Somehow I managed to squirm down into the sandy soil. As the truck passed over me, I felt the axle scrape against my scalp. Thankfully, I was still in one piece, but my refuge was gone, and I had no idea what had become of the leopard. I instinctively began to run, but as I scanned the area for a tree to climb, I heard Dad’s voice calling out to me, “Tom, are you alright?” I stopped, looking over my shoulder and saw the leopard lying still on the ground, 20 yards away.

Just then Chip called out, “We have a problem over here.” Reese was bent over at the waist, motionless. There was no obvious sign of injury, but his heavy jacket was shredded. When we removed the jacket, we saw his gaping wounds. Bite marks the size of quarters exposed the raw flesh in his arm. The leopard’s claws had opened deep, nasty cuts on his knee, hand and neck. Reese needed medical attention, and fast. After applying a tourniquet and securing him in the cab for the long trek back to camp, we were finally able to discuss what had happened.

Neither Jeff nor Dad had shot the leopard as I had assumed. Chip had watched the attack from his vantage point in the rear of the truck, trying to keep out of harm’s way. When my rifle landed at his feet, he grabbed it clumsily with his one good hand and somehow expelled the fired cartridge. From only a few feet away, he watched Reese and the leopard tangle. Reese was literally hanging off the side of the truck, punching the leopard frantically with his free fist as it gnawed on his other arm. It was a desperate struggle, one that Chip knew Reese couldn’t win. Chip inched toward them, and when it appeared that Reese and the cat had separated for an instant, he fired. The bullet missed, gouging a big chunk of metal out of the roll bar. A ricocheting bullet could easily have killed anyone in proximity, but luck was with us, and it landed harmlessly. Chip fired a second shot, dispatching the cat. When the leopard dropped to the ground, the driver started the engine to try to get away, not knowing whether the leopard would recover or that I was underneath the truck. Chip, broken hand and all, had saved the day.

I felt terrible. I could have prevented the whole thing if only I had killed the leopard when it charged. How could I have missed at such point-blank range? I cursed the damn scope.

After examining the dead leopard, Jeff walked over to me and said, “You know, you probably saved your brother’s life.”

I thought it was a bad joke, but then Jeff showed me the bullet hole in the leopard’s broken paw, which Jeff said had prevented the cat from getting a stranglehold on Reese. If that paw had not been broken by my shot, Jeff assured me, the leopard could have easily delivered a fatal bite to Reese’s neck.

How ironic, I thought, a broken hand had hindered the leopard, but not Chip. I was glad it wasn’t the other way around. I felt a little better, but Reese wasn’t out of the woods yet.

Reese never said a word the whole way back to camp, and we feared that he was in shock. We also worried that he might bleed to death or that infection could set in. The victims of leopard maulings often succumb to infection caused by bacteria in the decaying flesh within the claws.

We arrived in camp just before dusk, too late to summon a plane from Maun, the nearest town. A small plane could land on the dry pan adjacent to camp, but only during daylight. Reese was going to have to make it through the night.

We carried Reese to the dining table where we treated his wounds. Jeff dipped Q-tip swabs in alcohol and plunged them into Reese’s arm. Though he was obviously in a lot of pain, Reese didn’t utter a sound, except to ask the trackers to bring the dead leopard into the dining tent so he could see his foe, face to face. I knew at that moment that my little brother had grown up on that makeshift operating table deep in the Kalahari.

At dawn the next morning a small plane arrived with Maun’s only doctor. Reese and my parents were whisked away to a hospital in Johannesburg, the nearest treatment center. We learned by radio that night that the prognosis was good and that the doctors expected to release Reese from the hospital after only a few days. What a relief. It mattered little that we would have to return home, aborting our month-long safari after only a few days.

Upon release from the hospital, though, Reese surprised us all by announcing that he wanted to stay and finish the safari. “We came to Africa with a purpose,” he said, and “I’m not about to let a small setback like this spoil our trip.”

Upon release from the hospital, though, Reese surprised us all by announcing that he wanted to stay and finish the safari. “We came to Africa with a purpose,” he said, and “I’m not about to let a small setback like this spoil our trip.”

We remained on safari for three more weeks, and Dad and I collected all of the trophies we wanted. The most important one, though, didn’t belong to either of us, but to Reese, who now proudly displays the leopard for all to see.

Sporting Classics’ Africa includes forty-one adventures from the Dark Continent. The works of writers such as Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt and Markham grace these pages. Buy Now

Sporting Classics’ Africa includes forty-one adventures from the Dark Continent. The works of writers such as Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt and Markham grace these pages. Buy Now