I felt something warm above my head and realized the bear was drawing my whole face into its mouth; my nose, already in it and feeling the heat of it…

Have you had summer in Moscow and St. Petersburg this year? “the bundled-up June tourist asked at the train depot as wind buffeted him and rain fell in torrents.

“Yes, we have,” replied the local standing nearby. “But I was working indoors that day.”

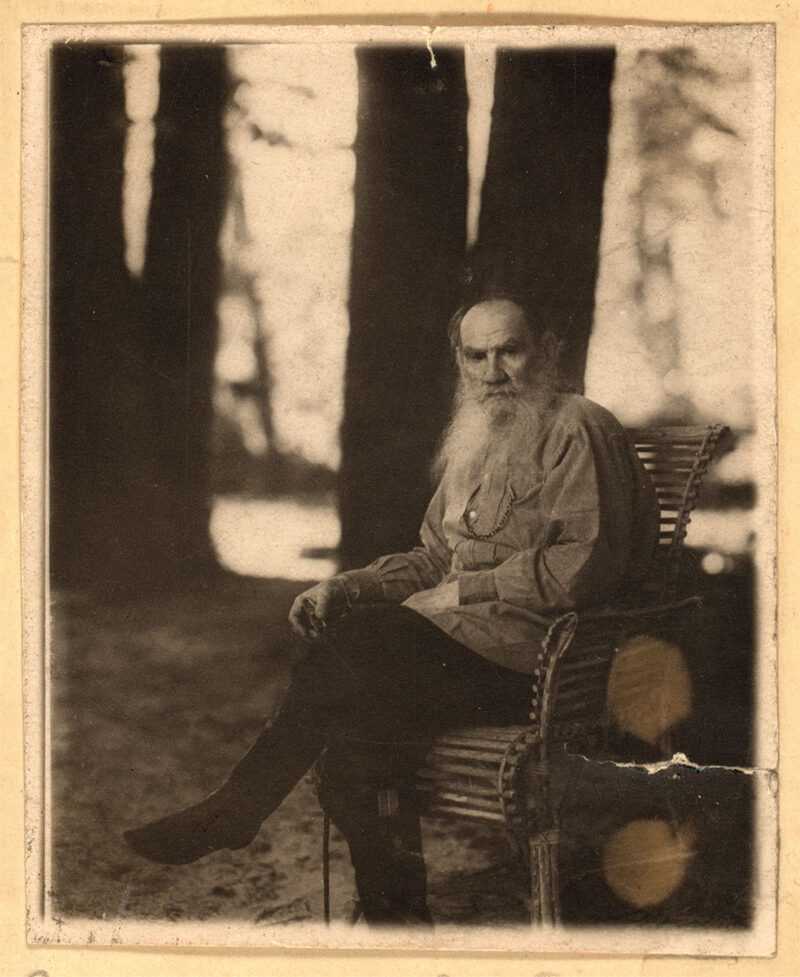

A portrait of Count Tolstoy taken outside his home in lasnaia Poliana, circa 1908.

To live near the Arctic Circle and Baltic Sea where inland rivers and marshlands freeze, when snow covers the ground around Moscow and St. Petersburg from 150 to 275 days a year with drifts tall as houses, a place of whiteouts, winter temps hovering between minus 10 to 30 degrees, high clouds that dissuade sun’s penetration, summer highs in the 50s and frequent, severe, climate changes, a man has to understand weather and know how to survive in it.

Leo Tolstoy, or Lev (Lyef) Nikolayevich Tolstoy, lived the better part of his life in the country around northwestern Russia and looked to the skies for 82 years.

Tolstoy was born August 28, 1828 at Yasnya Polyana, his wealthy mother’s estate in the Tula Province some 130 miles southwest of Moscow, the fourth of five children; three older brothers and a year younger sister.

His mother, born Princess Marya Volobskaya, died when Leo was two, and his father, Count Nikolay Tolstoy, a retired lieutenant colonel and veteran of the 1812 Patriotic War with Napoleon, survived his wife by seven years, dying of consumption alone on a street in St. Petersburg in 1837.

Tolstoy’s house, Circa 1908

Tolstoy was raised by two aunts who employed many serfs at the estate, including a tutor, horse trainer and hunting guide. In the years before he gave up hunting, Tolstoy wrote about shooting quail, ducks, tigers, jackals, boar hogs and stags, and stated in his diary that he’d become, “a tolerable shot.”

In his novel, Anna Karenina, published in 1877, the character, Levin Konstantin, is a self-portrait of Leo Tolstoy, and most of the people in the book are based on those he knew and events he experienced during his lifetime. Tolstoy held the same social position as Levin in the book, and had the same, wild nature, ideas and opinions, a passion for hunting and love of Russian peasants.

In Anna Karenina, Tolstoy describes a hunter and his dog on a hunt for snipe:

“Spring – beautiful; tender, without the disappointments of normal springs – one of those rare beginnings that rejoice plants, beasts, and man alike. The lovely weather stimulated me as I put on big boots and, for the first time, a cloth jacket instead of my fur coat. The place I was going to shoot was not far off in a little aspen-grove by a stream.

“Reaching the copse by horse, I dismounted, waded across a swampy glade, already clear of snow to a double birch tree and, leaning my gun against the fork of a dead lower branch, took off my coat, tightened my belt, and worked my arms to see if I could move them freely.

“Gray old Laska, my dog, following close on my heels, sat down opposite me and pricked up her ears. The Sun was setting behind the great forest with birch trees dotted about in the aspen grove standing clear in evening glow with their drooping branches and swollen buds ready to burst into leaf.

“I heard a shrill whistle in the distance and, two seconds later – the interval the sportsman knows so well – another followed and then a third, and after the third whistle the sound of a hoarse cry.

“I looked to right and left, and there, straight in front of me against the dinky blue sky, above the blurred tops of tenderly sprouting aspens, I saw a bird. It was flying straight toward me; its guttural cry, like the even tearing of strong fabric, sounded close to my ear; the long beak and neck of the snipe already visible. I took aim, pulled the trigger, and was rewarded to see the bird drop like an arrow then flutter up again. Another flash, followed by the sound of a hit, and beating in wings as though trying to keep up in the air, the snipe stopped, remained stationary for a moment and then fell with a heavy thud on muddy ground. The sport was excellent. I shot another brace of which one was recovered.”

Who was this Russian hunter, novelist and philosopher, considered to be one of the world’s best writers?

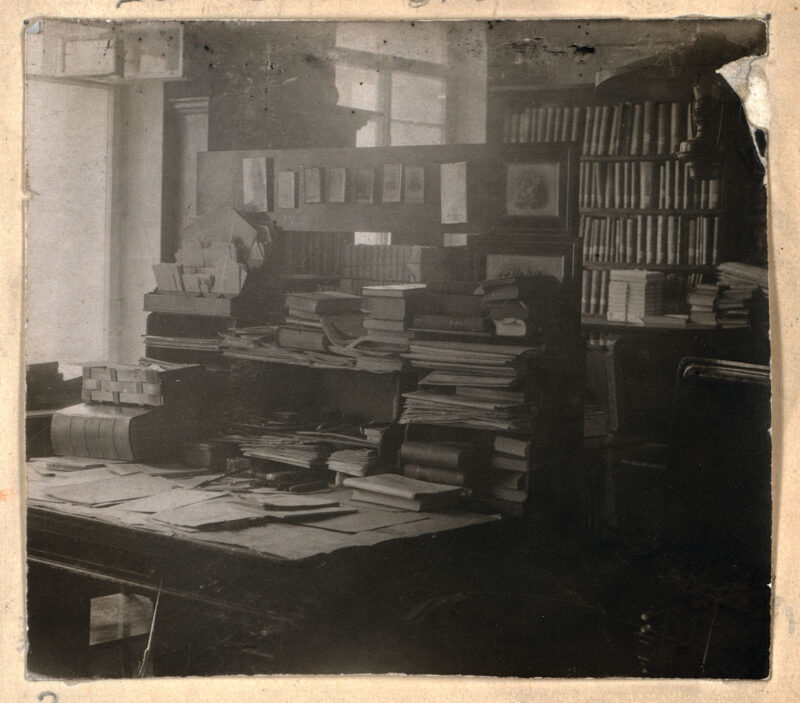

Tolstoy’s study, circa 1908

Tolstoy wrote short stories and books, had illicit sexual affairs with gypsy women that caused him unending mental and physical pain, and followed his brother Nikolay into the army as a civilian for two years before applying for, and receiving, an officer’s commission. He served in the Caucasus, Sillistra and the Crimea as a gunnery officer, then once out of the army, he married and had 13 children. He continued to pursue wild game until 1878, when he gave up hunting on humanitarian grounds.

There’s a Russian saying that if the first shot brings down bird or beast, the sport will be good. In his1854 autobiographical novel Boyhood, Tolstoy relates a hunt for a Russian stag:

“Fall – the muddy trail dropped off into a steep hollow. I went down under the wooded slope where cold wind blew. Half a mile further, the road turned up a hill emerging from the woods to poke through a field where a brace of quail were flushed out and flailed away toward a creek and whistling wind. In spring, the mountains around me turn violent green, billowing low under the sky. Spring never comes slowly. One morning it’s just there, the air rank with the smell of it.”

The first drops of rain splattered against my fir cap as I tracked the great stag across broken ground and back into timber. I stopped, checked my gun and then moved on. In cold silence of November stillness, I was alone, a hunter upon the shoulder of the mountain.

“Through the embroidery of twisted limbs of birch trees, I made out a dark shape a hundred meters in front. I traced the shape of the stag with my eyes util I saw the great rack, raised my gun and fired just behind a visible left shoulder. I heard a plop as the ball hit a tree trunk near where the stag stood, tree limbs deflecting the shot. At the flash of fire and noise, the stag exploded away, tearing left. I listened until I could no longer hear the sounds of breaking limbs — the hunt was over.”

Tolstoy did not like talking and hearing about the beauty of nature when out in it. Words, for him, distracted from the beauty of what he saw and felt, often electing to hunt and fish alone, or placing himself at a distance from other hunters.

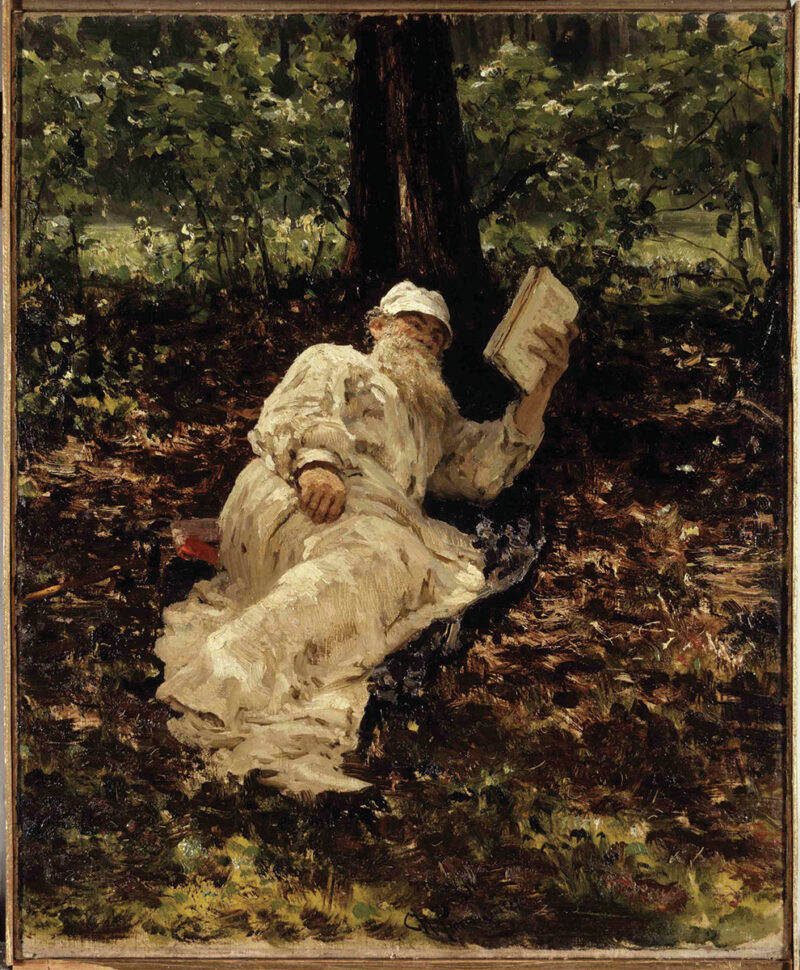

ToIstoy Ploughing by lIya Yefimovich Repin

Again, from Anna Karenina:

“Spring – when I came out of the woods all my attention was engrossed by the Sight of fallow-land on the slope of a hill, yellow with grass or trampled and checkered with furrows, in some parts, dotted with heaps of manure, or even ploughed.

“Morning dew still lingered at the roots of the thick undergrowth of grass near a river where carp were caught. I sat down by a bush, arranged my tackle, tossed line out into the water and waited. Hours later, when nothing took my bait, I still found pleasure at the side of the river, listening to the rush of water, seeing small birds dart about from tree limb to tree limb, and tasting the smells of summer ripening.”

In the winter of 1858 Tolstoy went on a bear-hunting expedition. Later, he published the following account in “The Bear Hunt,” one of 23 Short stories in Anna Karenina.

“My comrade shot a bear but only grazed him. There were traces of blood in snow, but the bear was gone.”

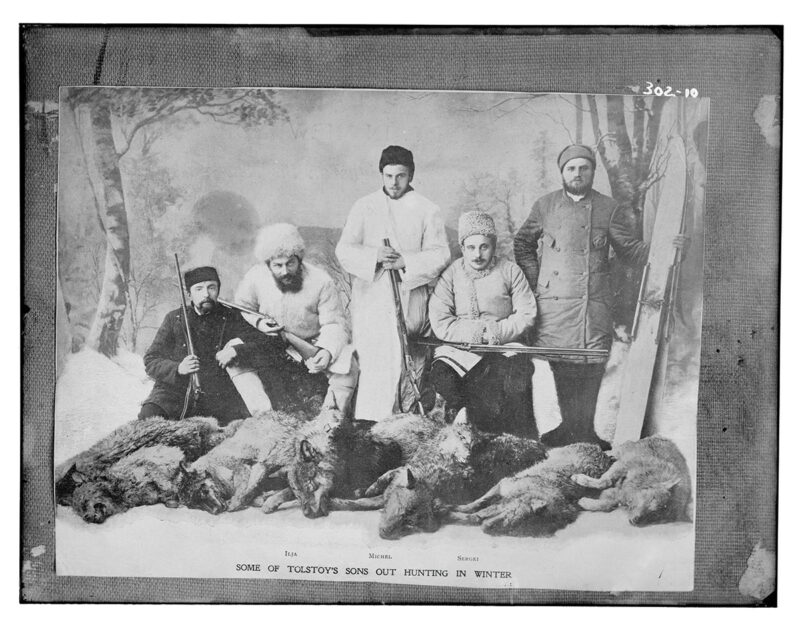

Tolstoy’s sons (he had 13 children) pose with wolves, which they probably tracked and killed with the help of hounds. The celebrated author hunted wild game until age 50, when he quit eating meat and began preaching non-violence.

A discussion of whether to pursue the bear or wait for several days to let it settle down, ensued between an old, peasant, bear-driver and a young one named Damian. Damian said the bear would not go far in deep snow, and knew he could track around it to see where it bedded down. Damian and I would stalk the bear. We took bread, examined our guns, and after tucking skirts of warm coats into our belts, we started off, following the bear’s track.

“The weather was fine, frosty and calm, but it was hard work snowshoeing in deep, soft snow not caked together, so our snowshoes sank six inches deep and sometimes more. The bear’s track was visible from a distance, often sinking in up to his belly and pushing up snow as he went on. When the bear’s track turned into a thicket of small firs, Damian stopped.

“We must leave the trail now,’ said he. “He has probably settled somewhere here. You can see by the snow that he’s been squatting down. We’ll go around; but we must move quickly. Don’t shout or cough, or we shall frighten him away.’

“Leaving the track, we turned left, went about five hundred yards when we spotted the bear’s track again and followed it out to the road where we stopped, looking to see which way he had gone. In snow, were prints of the bear’s paws, claws and all heading toward the village, and there were marks of peasants’ bark shoes.

Damian said we would see from his track where he turned off, to right or left in soft snow at the roadside. Walking the road for nearly a mile, we saw the bear’s track turn off. Damian examined the track that did not go from the road into the trees, but from the forest onto the road! Toe prints were pointed toward the road.

“That must be another bear,’ I said.

“Damian looked and considered for a while. ‘No,” said he. ‘It’s the same bear. He’s been playing tricks, and walked backwards when he left the road.’

“We followed the track, and found it really was so! The bear had gone some ten steps backwards, and then, behind a fir tree, had turned around and gone straight ahead toward a marsh where Damian thought he would settle down.

“We started around the marsh through a fir thicket. I, tired out by then, glided onto juniper bushes that caught my snowshoes tearing them from my boots. I stumbled over stumps or logs hidden by snow, while Damian glided along as if in a boat, his snowshoes moving as if of their own accord, never catching against anything, nor slipping off. Damian took my fur coat, slung it over his shoulder and kept urging me on.

“We covered two more miles, and came out on the other side of the marsh where Damian stopped and waved his arm. When I came up, he bent down, pointed with his hand, and whispered, ‘Do you see the magpie chattering above that undergrowth? It scents the bear from afar. This is where he must be.’

“We turned off, went on for another half mile until we came to our old track, having completely circled the bear in our days travel. Stopping, we removed caps and loosened clothing, were as hot as in a steam bath and as wet as drowned rats. It was time to rest.

“Evening glow already showed red through the forest as we took off snowshoes, sat down on them and got bread and our bags. I first ate snow, and then bread that tasted so good I thought I’d never in my life had any like it before.

“We rested until it grew dark. Then Damian flattened down the snow, broke off fir branches and made beds. We lay down side by side, resting our heads on our arms. I did not remember falling asleep, but two hours later I woke up, hearing something crack in the thicket.

“Hoarfrost had settled in the night. Damian was covered with it as was my coat as I rose and woke the tracker. We put on snowshoes and started for the village and beds.

“Morning came, and Damian had already gone out to check the bear and was back gathering beaters from the village. I dressed, loaded my guns, got in a sled and after driving two miles along the road, came near the forest and saw clouds of smoke rising from a hollow where peasants waited, both men and women armed with cudgels and roasting potatoes.

“Damian was there, and when I came up, led 30 men and women in a circle around the place where the bear was. The snow so deep, they could only be seen from the waist up. I and another hunter followed in their tracks. With the beaters in place, Damian came back and showed us where to stand.

“Trample the snow around you so you can move freely when the bear comes,’ said Damian.

“My reply, ‘I’m going to shoot the bear, not fight it.

“To my left were tall fir trees with visible space between them. A beater stood far off, waiting. In front of me was a thicket of young firs, about waist high and weighed down with snow and stuck together. Through them ran a path leading into the thicket where the bear was. Damian placed me near the path and my friend some distance to my right.

“I examined my guns, set one behind me against a tall fir and, just as I finished, I heard Damian shout, ‘He’s up! He’s up!

Book cover for Tolstoy’s Walk in the Light and Twenty-Three Tales

“At Damian’s shout, the peasants yelled and beat sticks against trees, driving the bear toward us. I trembled, holding my gun fast. Suddenly, to my left, I heard something fall in snow and looked between fir trees. Fifty paces off behind the trunk of a tree I saw something big and black — the bear. Taking aim, I waited.

“Seeing the bear move his ears and turn to go back, I caught a glimpse of his immense profile, and, in my excitement, I fired and heard the bullet go ‘flop’ against the tree. Peering through smoke from my gun, I watched the bear rush back toward the beaters.

“I reloaded my gun, thought I would not get a second chance, and heard a woman to my right scream that the bear was near her. I saw my hunter friend rise, take aim and fire. But he did not go toward the bear. Had he missed?

“Then something was coming toward me like a whirlwind, snorting, with snow flying up all around. It was the bear; rushing along the path through the thicket barely six dozen paces away. I saw all of him, black chest, an enormous head, and could see by the bear’s eyes that he was mad with fear; rushing blindly along.

“I raised my gun, fired and missed, the bullet going past the bear. I lowered the gun and fired again, hitting, but not killing it. The bear raised his head, locked eyes with me, bared his teeth and charged. I turned, snatched up the other gun, but almost before I touched it, I was knocked facedown in snow as the bear flew past.

“I tried to rise, but the bear whirled around and pounced on me with the whole weight of his body. I felt something warm above my head and realized the bear was drawing my whole face into its mouth; my nose, already in it and feeling the heat of it. All I could do was draw my head down toward my chest away from the bear’s mouth, trying to free my nose and eyes, while the bear tried to sink teeth.

“Then the bear managed to seize my forehead just under the hair with teeth from his lower jaw, and flesh below my left eye with his upper teeth, and start to close his mouth. It was as if my face was being cut with knives. I struggled to get away, while he made haste to close his jaws, growling like a dog. I managed to twist my face away, but he drew into his mouth again.

“The bear’s weight was suddenly gone as he rushed away. I looked up and saw Damian, without a gun, and with only a switch in his hand, rush the bear shouting, ‘He’s eating my master! He’s eating my master! You idiot bear! Leave off! Leave off!’

“When I rose, there was so much blood on the snow it looked as if a sheep had been killed and butchered. Flesh hung in rags above my eyes and below my left eye, though in my state of excitement, I felt no pain. ‘Where’s the bear? Which way did he go?’ I shouted. Suddenly I heard.

“He is here! He is here!’

“Once again, guns were raised as he rail past, bleeding. I wanted to follow him, but by then, my wounds had become very painful, so I went with Damian to the village, and to a doctor who sewed my face up with silk thread.

“One month later, I and Damian went after the bear, and Damian killed him. The bear’s lower jaw had been broken, and one of my bullets had knocked out a front tooth. He was huge. I had him stuffed, and he now lies in my room.”

Tolstoy wrote his greatest book, War and Peace, between1865 and 1869. He did not see it as a novel, but as a study of social and political issues in 19th-century Russia during the war against Napolean. The massive book includes 580 characters, both historical and fictional.

Tolstoy as painted by Russian artist Ilya Yefimovich Repin.

Less than a decade after completing War and Peace, Tolstoy stopped hunting and eating meat, and began preaching nonviolence. He led a rustic, simple life, and eventually became an anarchist who considered wrong all organizations based on the premise of force, including his own government and church.

After leaving his estate in 1904 so as to abandon all earthly goods, Tolstoy evoked a permanent breach between himself and his wife and followed his conscience as a wandering ascetic. His children, with the exception of youngest daughter, Alexandra, sided with their mother.

Following a brief visit to his beloved Yasnya Polyana estate in 1910, Tolstoy left home in the company of Alexandra, caught a chill and died of pneumonia at the railroad station master’s house at Astapovo on a cold November day in 1910.

Elephant. Bear. Moose. Rhinoceros. Buffalo. Lion. Since prehistoric times man has hunted. An elemental part of life, seeking out and overpowering large, strong, and fast animals has been a pivotal part of human evolution.

Elephant. Bear. Moose. Rhinoceros. Buffalo. Lion. Since prehistoric times man has hunted. An elemental part of life, seeking out and overpowering large, strong, and fast animals has been a pivotal part of human evolution.

In later times, when hunting for food wasn’t necessary, man still tracked down his prey. Following an instinct for adventure, for the thrill of defeating formidable opponents, man hunted. Buy Now