Aspiring elephant hunters dream of large tusks and an elephant hair bracelet on their right arm.

Before the turn of the 20th century, natives living in remote regions of Africa begrudgingly shared their home ranges with elephants. They were often forced to defend their villages, crops and their lives from marauding elephants — sometimes they killed the elephant, and sometimes the elephant killed them.

By way of bush logic and witch-doctoring, they came to believe that elephant hair embodied strong powers and that wearing elephant hair would protect them from being killed by an elephant. Wearing the hair crafted into a bracelet also indicated the wearer’s participation in an elephant skirmish.

By way of bush logic and witch-doctoring, they came to believe that elephant hair embodied strong powers and that wearing elephant hair would protect them from being killed by an elephant. Wearing the hair crafted into a bracelet also indicated the wearer’s participation in an elephant skirmish.

The first Europeans to learn of this custom were almost certainly the early professional ivory hunters, including men such as F.C. Selous, Major P.J. Pretorius, Karamojo Bell and James Sutherland. Venturing into dangerous and often hostile lands, these men didn’t want to buck local beliefs or possibly tempt fate, so they often adopted the native customs and traditions of the region. Besides wearing an elephant hair bracelet was simple enough — especially if there might be any truth to the beliefs.

Back in the 1950s and ’60s tourist shops in Nairobi and Mombasa featured numerous game curios including elephant hair bracelets, which were mostly thin, poorly made and cheaply priced. On the other hand, so to speak, were the thick, finely-made elephant hair bracelets that came from hunted elephants and worn by professional hunters and their safari clients. If you knew one of those men and admired his bracelet, he just might take it off and give to you — but never ask to buy it.

Short stubby hair covers most of an elephant’s body, but it’s the long strands of hair growing on the tail that provides the bracelets. Hair on the tail can grow as long as a man’s arm and assumes the thickness of heavy fishing line that ranges in color from black to the highly-coveted, lighter shades of amber, gray and white. If the authenticity of elephant hair is questioned simply touch the hot end of a match to the end of a strand. Plastic will melt, straw will burn, but real elephant hair will singe and smell exactly like burning your own hair.

Short stubby hair covers most of an elephant’s body, but it’s the long strands of hair growing on the tail that provides the bracelets. Hair on the tail can grow as long as a man’s arm and assumes the thickness of heavy fishing line that ranges in color from black to the highly-coveted, lighter shades of amber, gray and white. If the authenticity of elephant hair is questioned simply touch the hot end of a match to the end of a strand. Plastic will melt, straw will burn, but real elephant hair will singe and smell exactly like burning your own hair.

When an elephant is downed, tradition has it that the tail be cut off to establish rightful ownership of the tusks, skin and meat. Extracting the tusks from the skull requires about four hours of skillful axmanship to chop out the tusks. Back at camp, bracelets would be made by either the skinner or one of the trackers who knew how. The bracelet is worn on the right arm if having participated in the hunt — when presented to friends they are considered good luck tokens to be worn on the left arm.

The hairs are normally plucked (not cut) from the tail and soaked in warm water, which causes the normally stiff hair to become very pliable. Five to 15 strands of hair are then encircled to overlay each other. Utilizing small slivers of sticks as tools, intricate and often elaborate knots are tied at the ends of the encircled and overlapped strands. Tying the intricate knots is a skill handed down from one generation to the next as traditions of the hunt were honored.

The bracelet was then left to dry, which set the knots to the hair’s original stiffness The bracelet is then rubbed with elephant fat from the skull’s cellular structure, which, like lanolin, prevents the hairs from becoming dry and brittle. The ingenious design allows the bracelet to be enlarged by sliding the knots toward each other so that it can fit over the hand and then be tightened when positioned on the wrist.

Peter Barrett describes in, A Treasury of African Hunting, the downing of a trophy bull in Kenya in the late 1960s. “Before us lay a great pair of sweeping, curving tusks that were beautifully symmetrical,” Barrett wrote. “But the most exclusive elephant trophy of all can be had for the asking in camp. The tail of a worthy bull has stiff hairs anywhere from 10 to 18 inches long and about as thick as tennis-racket strings. A few of these hairs can be braided into an adjustable bracelet. This elephant, being old, had white tail hairs — just enough for one bracelet. Many a successful hunter proudly wears such a bracelet made from his bull as a lucky piece. Very few sport a white bracelet, however.”

Peter Barrett describes in, A Treasury of African Hunting, the downing of a trophy bull in Kenya in the late 1960s. “Before us lay a great pair of sweeping, curving tusks that were beautifully symmetrical,” Barrett wrote. “But the most exclusive elephant trophy of all can be had for the asking in camp. The tail of a worthy bull has stiff hairs anywhere from 10 to 18 inches long and about as thick as tennis-racket strings. A few of these hairs can be braided into an adjustable bracelet. This elephant, being old, had white tail hairs — just enough for one bracelet. Many a successful hunter proudly wears such a bracelet made from his bull as a lucky piece. Very few sport a white bracelet, however.”

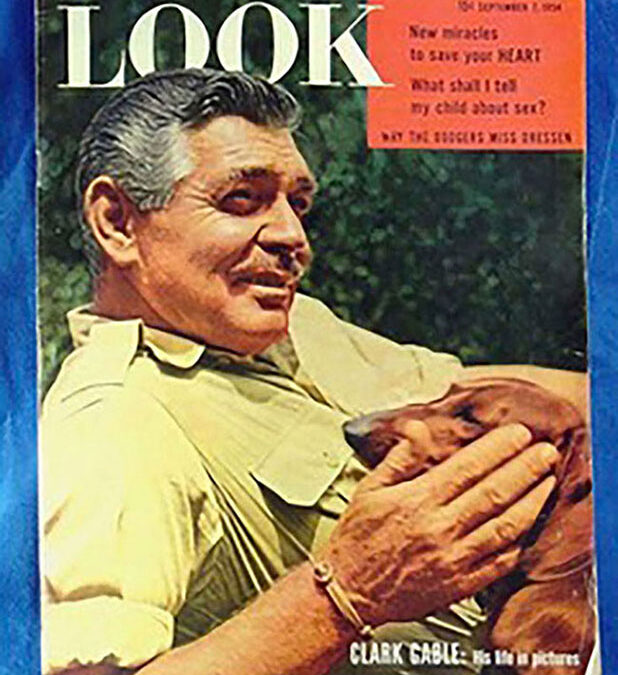

During the heyday of safaris in the 1960s, if you had lunch at the New Stanley Hotel’s sidewalk café or sipped a beer at the Norfolk Hotel’s Long Bar, you could spot professional hunters (PHs) and their clients by the bullet-looped, khaki bush jackets and shorts they wore — and by the cluster of elephant hair encircling their wrists.

The aura and legend surrounding an elephant hair bracelet became such that most hunters looked forward to proudly wearing this unique African wrist trimming. Sometimes they even became down-right obsessed by it. Following WWII, a 30- to 45-day elephant hunt in Kenya provided the visiting hunter with an excellent chance of collecting a trophy pair of tusks, but elephant hair was never guaranteed.

In fact, the lack of tail hairs, especially on an old bull, is not uncommon, much like older men who are often bald. Back in the early 1960s, writer Robert Ruark enjoyed extreme good fortune when he collected a huge trophy bull in northern Kenya with Harry Selby. After admiring the massive tusks, he then walked around to the other side for a look at the elephant’s tail and observed with some disappointment that, “…not a single hair survived on the bull’s obscenely naked tail.”

I’ve sported elephant hair ever since a fine thick bracelet was made for me from the arm-length tail hairs of my first elephant taken in Kenya more than 40 years ago. The bracelet garners interest and curiosity when I travel and, although I can’t confirm or deny the existence of any mystical powers, I can tell you that while wearing it, especially in large cities, I have no fear of charging elephants.

***

Another sportsman also hunting in Kenya in the late 1950s endured disappointment for lack of hair on his elephant’s tail. As the tale was told to me, the otherwise satisfied client had been very pleased with collecting a fine 80-pound elephant. But inspection of the tail, which sported so few hairs that not a single bracelet could be made from it, was a bitter disappointment for the client.

“Call for another elephant license,” he demanded. “Tusks be damned — this time we hunt for hair!”

His PH, who thought it an odd request, couldn’t sway his client from taking out another elephant license — for the hair. Somewhat reluctantly, the PH radioed his safari company in Nairobi and requested another elephant license be issued to his client. The issuance and delivery of a second license to camp took three days. With the fresh elephant license in hand the PH and his client once again prepared to hunt elephants, only now they’d be looking at elephants’ backsides.

His PH, who thought it an odd request, couldn’t sway his client from taking out another elephant license — for the hair. Somewhat reluctantly, the PH radioed his safari company in Nairobi and requested another elephant license be issued to his client. The issuance and delivery of a second license to camp took three days. With the fresh elephant license in hand the PH and his client once again prepared to hunt elephants, only now they’d be looking at elephants’ backsides.

“I have a fine pair of tusks, with which I’m very pleased,” the client reiterated, “so we need not be concerned with tusk size. I’m only interested in the tail.”

It wasn’t long before they happened upon a bull elephant’s enormous backside sticking out of a patch of thick bush on which the elephant fed. Staring at the wrinkled, baggy pants-looking elephant butt, they couldn’t help but notice the mass of light-colored hair that hung like broom straw from the end of the swinging tail.

“That’s a brilliant tail,” the client exclaimed excitedly. “Let’s take him.”

“That’s a brilliant tail,” the client exclaimed excitedly. “Let’s take him.”

“But wait! Let’s at least have a look at his tusks,” the PH pleaded.

“Look, I’ve got all the ivory I need,” the client pointed out. “It doesn’t matter what his tusks look like — his tail is magnificent.”

The PH resigned himself to the client’s eccentricities, permitting him to take a rear-angle shot at the point where the hip bones meet the backbone. The client fired and the bull dropped to a single shot, and with a quick insurance shot administered from the side the deed was done. The client was ecstatic over his trophy elephant tail, which would yield many thick, white elephant hair bracelets.

But, when they hacked the bush away from the bull’s head and tusks, the PH and his client became awe-struck as they stood back to stare disbelievingly at the tusks. There before them was a pair of tusks like the PH had never seen. Each tusk would weigh over 120 pounds, and measure more than nine feet in length. The PH silently and surreptitiously wiped a tear from his eye, sorely regretting not having had the honor of viewing such an elephant while the animal was alive and on his feet — for that is surely considered to be one of Africa’s most thrilling sights.

But, when they hacked the bush away from the bull’s head and tusks, the PH and his client became awe-struck as they stood back to stare disbelievingly at the tusks. There before them was a pair of tusks like the PH had never seen. Each tusk would weigh over 120 pounds, and measure more than nine feet in length. The PH silently and surreptitiously wiped a tear from his eye, sorely regretting not having had the honor of viewing such an elephant while the animal was alive and on his feet — for that is surely considered to be one of Africa’s most thrilling sights.

Once in Botswana, I had an overly-anxious hunting client that desperately wanted an elephant. But it was soon clear that his focus was not so much on the tusks, but aimed at the pachyderm’s nether regions. Apparently, he had promised elephant hair bracelets to a list of friends back home. Not appreciating the importance of this, I continued to judge the elephants we looked at by the size of their tusks without regard for their tails.

When he did finally collect a respectable 60-pounder (weight of heaviest tusk), my client viewed the tusks with indifference, but rather scooted around to view the all-important ass-end. When I heard him scream like a woman, I shot around to find him close to tears and staring slack-jawed at the elephant’s backside. I had to bite my lip to keep from laughing out loud, for not only was there no hair, there was not even a tail. The bull’s most private posterior part of his anatomy was exposed in uncovered glory like the bung hole of a 44-gallon drum. Not even a flap of skin provided a modicum of modesty for the elephant’s butt hole. I’d never seen anything like it, before or since.

When he did finally collect a respectable 60-pounder (weight of heaviest tusk), my client viewed the tusks with indifference, but rather scooted around to view the all-important ass-end. When I heard him scream like a woman, I shot around to find him close to tears and staring slack-jawed at the elephant’s backside. I had to bite my lip to keep from laughing out loud, for not only was there no hair, there was not even a tail. The bull’s most private posterior part of his anatomy was exposed in uncovered glory like the bung hole of a 44-gallon drum. Not even a flap of skin provided a modicum of modesty for the elephant’s butt hole. I’d never seen anything like it, before or since.

The client was visibly distraught, but managed to eventually perk up when I suggested he buy the required elephant hair bracelets at one of the curio shops in Victoria Falls. I was sure no one in his native Italy would know the difference.

This synthetic elephant hair bracelet is made to RESEMBLE the original elephant hair bracelet made from the tail hairs of the elephant. This light weight bracelet is made of 18-20 strands of synthetic hair and measures about 3/8ths of an inch wide. The strands are hand-wrapped with 14 Kt Gold fill X-knots for an attractive black and gold combination, fashionable and durable. Click Here to View All

This synthetic elephant hair bracelet is made to RESEMBLE the original elephant hair bracelet made from the tail hairs of the elephant. This light weight bracelet is made of 18-20 strands of synthetic hair and measures about 3/8ths of an inch wide. The strands are hand-wrapped with 14 Kt Gold fill X-knots for an attractive black and gold combination, fashionable and durable. Click Here to View All