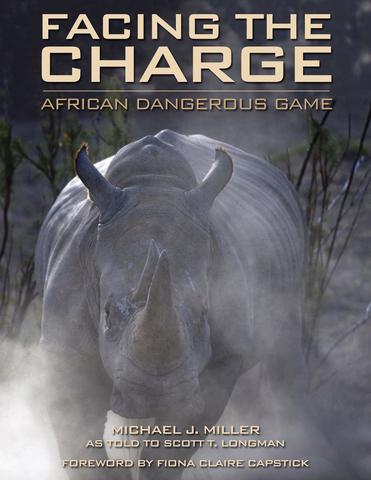

An excerpt from Facing the Charge, a safari book featuring adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting.

I hadn’t realized this as this particular adventure had unfolded, but, really, it all came back to Tanya.

She was looking at me now. Unhappy. Again.

What she said was: “Do you have to?”

It was a week after the Police Anti-Terrorist Unit visit. My PH, Rory, Tanya, and I, along with several staff members, had been on a long slog after buffalo that had managed to book the off-season someplace else, maybe Brighton. Rory knew that, while there were a great many outlying subgroups, significant parts of the herd tended to stay together. Which means that they should have been leaving tracks like Lee arriving at Gettysburg even before Longstreet had bothered to show up.

I’d gone from feeling bad about it to feeling petulant to feeling foolish to feeling downright unsociable. Hemingway has documented this perfectly predictable progression. So while I felt unsociable, my feelings were not unprecedented.

It was about 4:00 p.m., and that hour had significant teeth, because Lew wanted everyone back inside the compound by 6:00. The penalty for violating curfew was the all-too-real potential of getting ambushed by the Zambian African National Liberation Army. While I was extremely enthusiastic about shooting them into nano-pieces, I wanted to do it on my terms, not as our Toyota happened to pass through an ambush site with 20 of them behind cover with a great big box full of Soviet weapons.

Despite all that, Rory had pointed out to the peninsula.

The peninsula jutted out, too big to immediately recognize on the ground as a peninsula, into the Zambezi River. Lush and fertile and green and teeming with lots of things we hadn’t shot, to include particularly the trio of magnificent Cape buffalo bulls Rory had just pointed out.

Tanya had looked at me and, in combination of word and fatigued gesture, made it clear to perfection she wasn’t fighting through another two hours of densely intertwined vegetation just to let me go whack some ungulate.

I surveyed where we were. There were good views, and she would have three experienced members of the camp staff with her, not to mention that the staff had our spare hunting rifles and the L1A1.

I kissed her.

“All I want to do is shoot just one buffalo.” She nodded a reluctant acceptance, and Rory and I were off, moving downhill.

From the high ground we had, there was a good view of the ridge of the peninsula, and there were clearly three big buff there. I couldn’t tell how many more, but at least three. Even at this distance, they seemed big enough to be really good. My heart rate picked up.

As we descended, I learned firsthand the difference between having your heart rate rise at the prospect of gain (significant) and your heart rate rise at the prospect of cataclysmic disaster (it sounds like the mainsail on an America’s Cup craft ripping out). I learned that because Rory didn’t take us to the base of the peninsula.

He took us to the water.

I looked at him.

If you grew up in the Midwestern United States, as I did, water is fun. Water is friendly. Only very rarely does water take out some doofus full of Keystone Light on a jet ski. And absolutely nothing there ever ingests you.

Not so in the Zambezi.

Water there is all things bad. In Africa, your first thought of a body of water should be the same as when a smokin’ hot chick 25 years younger than you tries to pick you up in Mombasa. It’s not if you’re about to be taken out, but, rather, in what way and after how long a swim.

Water provides the avenue of access for creatures that want to ingest you. It is their hunting blind. It gives them their lure, and it is their avenue of escape. Quite literally, untold thousands of African humans, to the very day of this writing, die annually from the same organisms that inhabit the water as they did a millennia ago. Those predators range from itsy-bitsy to the size of your Hemi Durango.

On the former scale, the microbes in African streams are simply too much to address here, but among the rogues’ gallery of viri and bacteria and fungi and liver flukes and segmented worms is a subtle fellow who goes by the name of bilharzia. Bilharzia is a cross between a transdermal horse medicine and the worst case of syphilis in history.

In 1851 a man by the name of Theodor Bilharz figured it out. Ted had no idea what he was getting himself into, because for the next two centuries and counting, his name would be tied to one of the most hideously parasitic diseases known to humankind. If he had had any common sense, he would have operated under a pseudonym and blamed somebody else. But he didn’t.

So, essentially, a snail that lives in freshwater is infected with the stuff. The way it gets there is some human host tends to his or her ablutions in a river, whereupon the parasite leaves his body in the form of an egg that hatches into something called a miracidium. After that it zips around until it finds a snail.

The parasite assaults the poor snail through its foot. The stuff takes over its hepatopancreas, and there it proceeds to make huge numbers of things called cercariae. They are there for the sole natural-selection-dictated mission of creating more of themselves. And, boy, do they. It depends on lots of things, but, essentially, the snail has gone from peaceably being a snail to being a bilharzia factory. Every day the snail launches untold thousands of them into the surrounding water.

One of the dangers of bilharzia is that you don’t even need to drink it. All you need to do is get it splashed on you. Yep, one errant canoe paddle flip-up and you’re potentially hit. They land on your skin and can simply drill through it using a caustic enzyme. Once in, it acts like you are watching Aliens III, and it mutates itself into yet another form that then zips around your bloodstream looking for new quarters, like, say, your lungs.

By the time your symptoms show up, you’ve long forgotten your Zambezi splashing and are thinking it’s the flu. If you are so fortunate to find somebody competent to diagnose you, you then call in a violent series of chemical strikes on your own position that make World War I look like the Occupy Wall Street movement.

I shuddered.

The next major problem in the water has a lineal history of about 150 million years. Seldom does natural selection pop out a prototype, dust off its hands, call it good enough, and knock off for drinks. But that’s exactly what happened with the Nile crocodile. The unspoken but inescapable conclusion is that the craggy-toothed fiend was phenomenally good right out of the box. While at that point in my brand-new African career I’d not yet seen one in action, I’d read back to the Lost Library of Alexandria about them. Contrary to the occasional released-straight-to-video movie, they don’t have to be the size of a school bus to convert you to biosolids on the river bottom. In fact, if you cuffed up the sleeves on your 45R linen blazer, the saurian that would fit it is entirely up to the job of taking you down.

Assuming that their software evolved in cadence with their hardware, Lyle and friends have been operating in primarily the same way the whole time. They sit stock-still, mostly or completely submerged, at an ambush site and wait for palatable prey. Probably one of the reasons that they survive so well is that “palatable” to a Nile croc includes brushbuck, warthog, Kikuyu, rhino, lion, Shona, kudu, Swedes, badgers, Scotsmen, zebras, leopards, and essentially everything else. Including, as I was just then reflecting, handsome lads from North Dakota.

Upon having the prey hove into the ambush site, they execute the following operational order: surprise, strike, seize, shock, suffocate. That sequence is then followed by stash, season, and snarf.

The first three steps were those most closely holding my attention. If the croc was on the surface, we could look for the eyes. But if already submerged—and they can hold their breath like an Ohio-class submarine—the first we’d know of it was when one of us went under. And we would go under. The way a croc implements the strike, seize, shock part is to slam its long, heavy, needle-lined bear trap of a face on you, usually a limb, and then execute a high-torque spin down his longitudinal axis. I’ve since seen them do it. It looks like the lizard is on a high-RPM pig roast spit, except that the who-is-doing-what-to-whom is the wrong way around. Short of a creature having a good, healthy exoskeleton, that spin shreds muscle and tendon and nerve and ligament and arteries with resultant severe shock, generally resulting in the victim’s total inability to fight back.

I quietly cleared my throat and spoke softly.

“Hey, Rory. Why don’t we go down to the base of the peninsula instead, and walk out?”

He shook his head, looking in that direction.

“A good 500 yards to the base, then almost that far back again to get back to the buff. We simply haven’t the time. But crossing here will just about put them in our laps.” Without further discussion, he lifted his rifle high in one hand, eased his boots into the water, and began to swim.

My last act before entering the water was to think of the hippo. Most folks have the Disneyland picture of the mechanical hippo jaws opening in front of a safari boat full of wide-eyed kids from Akron. The Stetsoned college sophomore in the bow touches off a blank from a starter’s pistol, and the fiberglass incisors recede. That would not be recommended in reality.

In reality, the first reaction of everyone I’ve since known who has had a real hippo surface near their boat is the same as Roy Scheider’s in Jaws: “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.” And with good reason. While they may look like overstuffed knockwurst, the hippo is the strongest, meanest, most territorial, and most aggressive knockwurst in the world. More to the point, he often munches transoms right off watercraft the way you might tear the top off a box of Cracker Jack with your teeth. He then treats the passengers as the peanuts. He makes destroying boats look so effortless that actually crushing the passengers probably doesn’t fall within his definition of sporting, although once committed, you couldn’t tell.

It’s small comfort that, as an exclusive herbivore, he won’t actually ingest the pâté he makes of you. Oh, and the opening discussion I’d had with Lew emphasized that there were a lot of hippo in the area.

Lifting my rifle like Rory did, I scrambled into the water after him.

I remembered hearing that crocs feel for the uneven vibrations of injured creatures, so I was focusing on as smooth and even a stroke as you can manage while holding a Browning in one hand and No. 10 can of terror in the other. I’m still looking for an appropriate adjective to describe how I felt in that water. “Vulnerable” doesn’t even come close. Nor does “exposed” or “blind.” I wanted dry land worse than the combined crews of the Lusitania and Andrea Doria.

By the time I got there, Rory had already scrambled up and was covering me. He helped me clamber up the bank, and when he released my hand he put his index finger to his lips. Right. I’d nearly forgotten that we were within hopscotch range of three buff bulls.

And, oddly, the crossing helped me with that. Buff? Them I could see. Them I could shoot. They weren’t experts at drowning me.

We worked forward through the grass, rifles held at port arms, ready on the safeties. When we got about 40 yards from them, we eased up on a slight rise, maybe two feet higher than the surrounding land. It, too, was covered with the tall grass, so it offered us both a good vantage point and some concealment.

Right.

I took a good look at them. All were good, big bull bodies, good sweep and symmetry to the horns. But the one in the center was better than the other two. I whispered to Rory my choice, and he breathed back his agreement.

Before firing, I took a quick but careful look at the muzzle to make sure that there wasn’t any errant Zambezi mud trying to turn the Browning barrel into a face-shredding pipe bomb—a trick for which Africa is known. Then I rested the receiver on my left wrist, cupped my left hand up, and oh-so-quietly eased open the action to eject the chambered round into my hand, to let any residual water in the barrel or chamber drip out. Then I rechambered, checked that the safety was off, and shouldered the rifle.

There was long, orange light from the west, the sun punching through the atmosphere at a flat tangent that was starting to suck out the blue-green end of the spectrum. Since we were more or less south of the trio of bulls, one side of them was brilliantly illuminated, and the other side was utterly opaque. I took a solid heart-lung sight picture, envisioned the bullet path through to the opposite shoulder, eased out half a breath . . . and squeezed.

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa home. Shop Now

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa home. Shop Now