It was hard hunting. The woods were open, the ground heavily carpeted everywhere with leaves.

The dogs were already out of sight, but I could see the sedge grass ahead moving and I knew they’d be making for the same thing that took my eye: a spearhead of thicket that ran far out into this open field. We came up over a little rise. There they were. Bob on a point and Judy, the staunch little devil, backing him not 50 feet from the thicket. I saw it was going to be tough shooting. No way to tell whether the birds were between the dog and the thicket or in the thicket itself. Then I saw that the cover was more open along the side of the thicket, and I thought that that was the way they’d go if they were in the thicket. But Joe had already broken away to the left. He got too far to the side. The birds flushed to the right and left him standing, flat-footed, without a shot.

He looked sort of foolish and grinned.

I thought I wouldn’t say anything and then found myself speaking:

“Trouble with you, you try to outthink the dog.”

There was nothing to do about it now, though, and the chances were that the singles had pitched through the trees below. We went down there. It was hard hunting. The woods were open, the ground heavily carpeted everywhere with leaves. Dead leaves make a tremendous rustle when the dogs surge through them; it takes a good nose to cut scent keenly in such dry, noisy cover. I kept my eye on Bob. He never faltered, getting over the ground in big, springy strides but combing every inch of it. We came to an open place in the woods. Nothing but big hickory trees and bramble thickets overhung with trailing vines. Bob passed the first thicket and came to a beautiful point. We went up. He stood perfectly steady, but the bird flushed out 15 or 20 steps ahead of him. I saw it swing to the right, gaining altitude very quickly, and it came to me how it would be.

I called to Joe: “Don’t shoot yet.”

He nodded and raised his gun, following the bird with the barrel. It was directly over the treetops when I gave the word and he shot, scoring a clean kill.

He laughed excitedly as he struck the bird in his pocket. “Man! I didn’t know you could take that much time!”

We went on through the open woods. I was thinking about a day I’d had years ago in the woods at Grassdale with my uncle James Morris and his son, Julian. Uncle James had given Julian and me hell for missing just such a shot. I can see him now, standing up against a big pine tree, his face red from liquor and his gray hair ruffling in the wind: “Let him alone. Let him alone! And establish your lead as he climbs!”

Joe was still talking about the shot he’d made. “Lord, I wish I could get another one like that.”

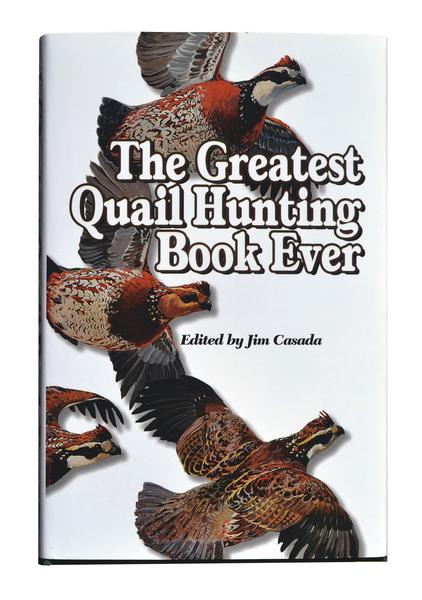

From the book The Greatest Quail Hunting Book Ever.

From the book The Greatest Quail Hunting Book Ever.

Read this story plus 38 others from those halcyon days when sporting gentlemen pursued the noble bobwhite quail with their favorite shotguns and their elegant canine companions. The 368-page book opens with compelling tales by the literary giants from quail hunting’s golden era, including Nash Buckingham, Robert Ruark, Havilah Babcock, Archibald Rutledge and Horatio Bigelow. Buy Now