My last buck — the last to date at Charlie’s and likely the last, though the unknown has yet to reach its terminus.

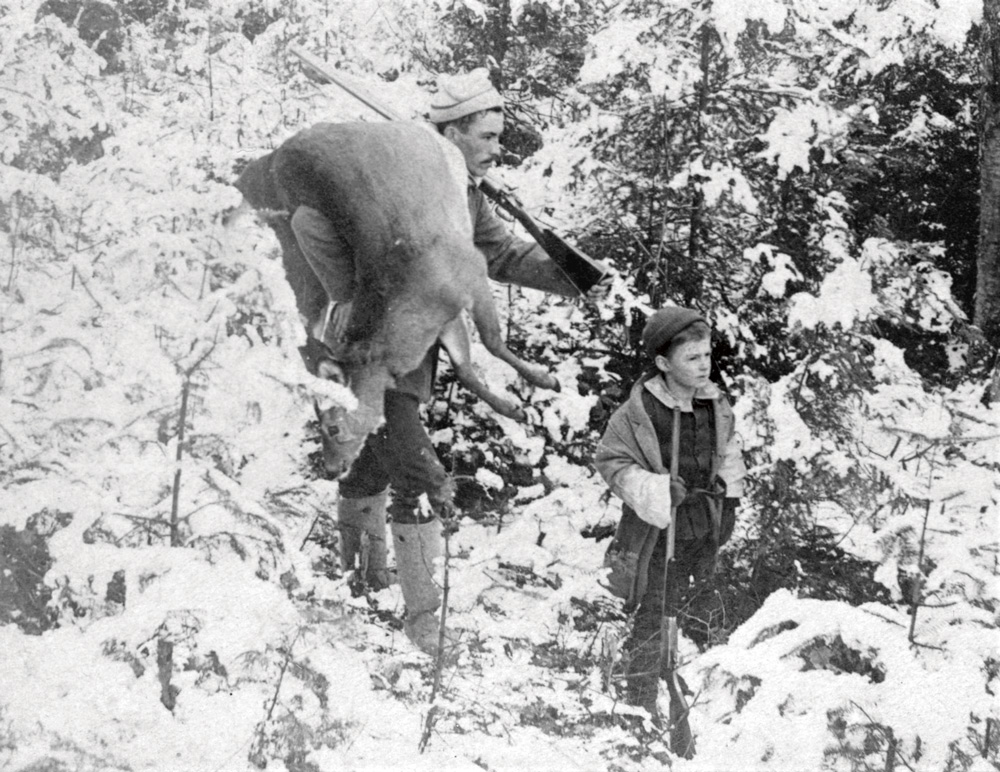

An early camp at Charlie’s.

Distraught. That definitive aptly portrayed the sentiments of both Neal and me. Current news, while not completely unexpected, put us on alert. Near two decades had been kind, had afforded us a rare opportunity. We had been handed leverage — this restricted to respectful and proper conduct — to camp on and hunt a sizable and productive block of quiet real estate where deer grew big and food supplies were abundant. The camp, our favorite, became known as Charlie’s. No additional nomenclature required. And now, according to that news, Charlie had suffered a significant decline in health. Anticipatory grief wrapped us in a bleak shroud.

Charlie owned that property. He grew up there farming the beneficent flat lands that ended abruptly to the east at an abutment of steep, sandy hills and severe hollows, these bristling with oaks and hickories, most of which mature and proffering prodigious supplies of mast each year. Those flat lands covered seasonally with soybeans, corn, and wheat. Maybe 700 acres total, 300 in those bluffs and hardwoods. A whitetail and gray-squirrel trove; our good fortune seemingly unmerited.

Canvas was eventually chosen as a far superior camp dwelling.

Neal came to know Charlie several years before I. The two of them, Neal and Charlie, were — as Southerners say, distant kin — through the marriage of a son of one family and daughter of another down the line from my two comrades. Neal had hunted Charlie’s place off and on, and he asked about me tagging along. Charlie graciously agreed. Immediately, a bond was formed. With Charlie pushing a decade older than I and I doing the same with Neal, we made an assorted trio, a brotherhood not restricted to age.

Kinton and his first deer at Charlie’s. The bow is a bamboo-backed Osage. Cedar arrows and two-blade broadhead worked well.

“I like the way y’all hunt,” Charlie told me somewhere along the third year at this venue as we sat around a campfire, two canvas tents reflecting the dance of seasoned oak. And that way referenced was as unique as the bonding: Old gear consisting of Osage longbows and cedar arrows; flintlock rifles and 18th-century buckskins and moccasins and waxed haversacks and wool coats; big Sharps rifles for which we loaded cast bullets and black powder; knives hammered out blacksmith style.

And the way included Charlie’s favorite, an apparent anomaly among modern whitetail connoisseurs: “Y’all hunt from the ground.” And for the most part he was right. With the exception of hanging a tree stand while employing longbows beside a woods trail, we did hunt from the ground. Quietly rambling ridge-top and hollow and eventually sinking into the embraces of oak bases, their outsized roots providing the services of a recliner. Maybe a blowdown out front or behind for enhanced cover. Seldom camo. Most often drab pants, an olive sweater. Unless we were in those above-mentioned buckskins. That and those were our ways Charlie so much admired.

A flintlock buck taken early in the history of Charlie’s Camp.

I recall with clarity my first deer at Charlie’s. A big doe. I scouted a knife-edged ridge standing 400 yards from the flat land and a ripened soybean field. An active trail evidenced, tangled thickets downslope to the east a sanctuary. To the west those beans. My climbing tree, a straight red oak at ridge peak, was only a few yards from that trail. A steep-angled shot in some situations. But it was a good choice. A dandy buck, early on and part of a scattered collection of his associates got past with no shot materializing. And later, that doe. Three more with her.

This quartet announced its arrival by gentle hoof-fall in autumn leaves. And there was that unmistakable crunch, pop as they picked up acorns along the way. My doe, 12 yards maybe off the peak and a broadside-offering given, skidded to a halt 30 additional yards down after a sharp two-blade entered and exited.

This buck was taken along the same ridge that produced Kinton’s first deer at the camp.

And there was another doe of memory. Buckskins and .54-caliber flinter this time. Three came from behind, my station the confines of a beech tree and root ball from a fallen comrade on the edge of a sand ditch. The deer’s crunching again. Fortuitous it was that they were on my right, the leftie that I am. The long rifle was in place, cock in battery, when that fat doe walked into the line of sight.

Suddenly, there was that clack, whoosh, boom common to the flintlock. An enormous and odiferous cloud of smoke filled a wind-free hollow of a late-afternoon wood. No visual, but the aural told a success story. Forty yards maybe; there would be no tracking demanded. Neal was off in the distance, already gathering his implements in preparation for the walk back to camp. He came to me. Another gesture of friendship, this much appreciated when the dragging began.

Neal Brown with a doe taken at Charlie’s Camp. A bamboo-backed Osage longbow handled the chore with ease.

And he, Neal, was consistently more productive in the deer woods at Charlie’s than I. Seldom did a day pass minus Neal either taking his game or restraining while in proximity of whitetails. And certainly there were no entire seasons that went lacking. Neal got deer; still, this was not the full intent of any hunt we made. Yes, we each wanted a deer; that happened on occasion. But many other matters were of greater import.

I still have a mental image of one particular arrival day. Separate trucks and gear, Neal got to camp first. As I pulled up he stepped away from a stack of firewood and smiled. ”The Good Lord just showed out with this day!” And He had – showed out, indeed. Bright; cool; autumn leaves fluttering in a brief breeze. A glorious day, a day given by the Creator. And we were the beneficiaries. Such elements as this enjoyment and recognition are a part, quite a significant part, of outdoor experiences. Records, had we kept them, would show that neither of us took a deer that trip. Didn’t even feel that rush of expectation from a rustling in forest duff or see a deer pass close to our woodsy domicile. Yet, contentment reigned. The intent of that trip was enjoyment, fraternity, praise for the Creation. These were abundant.

Coyotes are plentiful at Charlie’s. Neal collected this fine specimen – later skinned and the hide used – while using an 1874 Sharps loaded with black-powder cartridges.

Early on after we were firmly established, Charlie was a common fixture at camp. He drifted by each day around noon to garner reports of the morning and plans for the afternoon. But it was nighttime campfires he most enjoyed. All of us for that matter. We laughed and shared and often ventured into a modicum of country philosophy. Though I was and am the odd one and left-handed, in those matters of philosophy we all postured a strong leaning to the right.

As time passed and got closer to the recent, Charlie found himself absorbed in caregiving for his wife. He still came to the campfire but was restricted in time, this determined by a sitter doing an evening vigil. He eased away earlier and earlier as the days and months slid by. Before leaving each visit, he would turn to us and give his customary proclamation: “If I don’t see y’all before you leave, y’all know you’re are welcome to come back.” And we did know.

Steve Artman, a hunting comrade, shows off his flintlock doe taken during the same hunt when Kinton took his last buck.

My last buck — the last to date at Charlie’s and likely the last, though the unknown has yet to reach its terminus – came in a fashion common to our treasured camp. I took a measure of comfort in big roots at the base of an oak. That knife-edged ridge that gave me my first doe at Charlie’s was only a handful of yards upslope. A gray wool coat wrestled with gnawing wind. Daylight was struggling.

Unlike days past when a wooden bow or long rifle would accompany me, years had annoyed shoulders to the extent that a stiff bow was not an option. Neither were those bold barrel sights of a graceful flintlock. Still, I toted a classic: Ruger No. 1, Leopold attached, in an aging caliber less than familiar to a great many new shooters – 9.3X62, a 1905 creation of Berlin gunsmith Otto Bock. A true gem, this rifle. A proven performer, the 9.3X62. The setup amply acceptable to one possessing my proclivity.

Neal with a Charlie’s Camp buck, this deer taken with Neal’s 1874 Sharps loaded with black-powder cartridges.

At first there was a simple shuffle in leaves, this coming from another ridge to the east. Then an unquestioned rhythm that verified deer. The buck emerged from behind low limbs of a beech and worked his way to a tiny ditch. The rifle waited. A rumble from the round. A short distance was all the buck made. I walked to him, knelt in a prayer of thanksgiving. And as realization of what this event proclaimed wrapped me its sobriety, I wept.

The night was cold. Neal and I field dressed and hung the buck from a limb back at camp. Charlie was able to come the following morning. He was smiling, congratulatory, his usual self but halting to health. He didn’t stay long, but as he left he turned and said: “Y’all come back anytime you want.” That invitation was genuine, but the opportunity was tenuous, uncertain. Days were and life was moving, consuming, ruling. We now hold only faint hope of return.

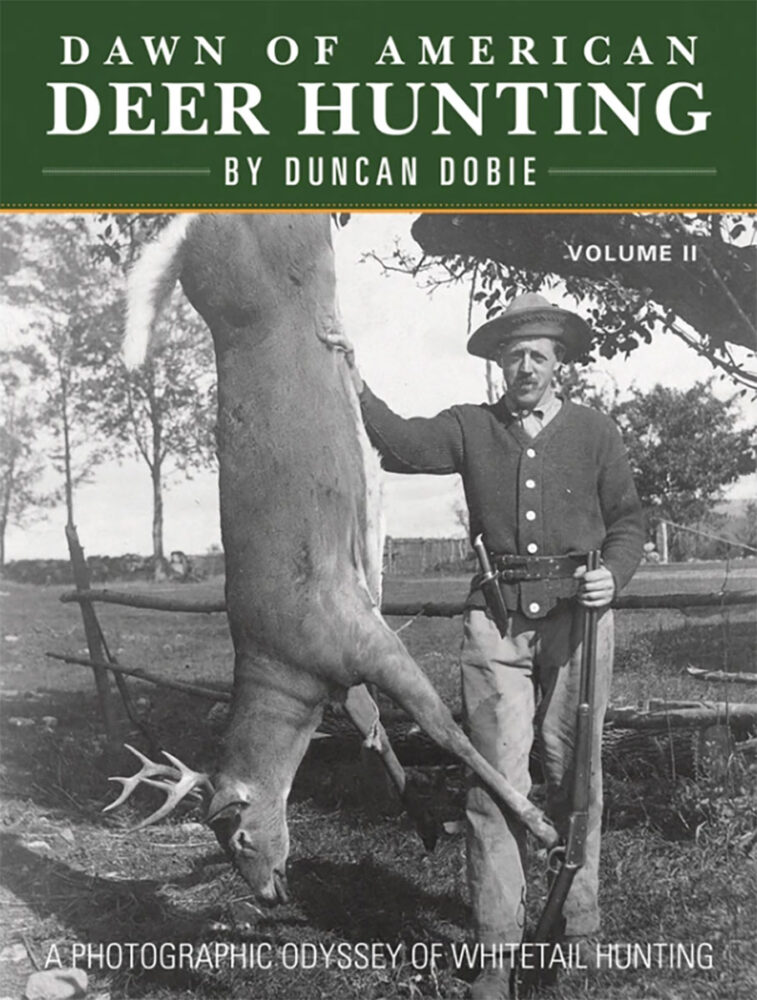

With the enormous popularity of the original Dawn of American Deer Hunting published in December 2015, author Duncan Dobie and Sporting Classics now bring you Volume II, chock full of amazing stories and facts, a breathtaking color section filled with eye-catching whitetail art and nearly 400 stunning black-and-white photos. Buy Now

With the enormous popularity of the original Dawn of American Deer Hunting published in December 2015, author Duncan Dobie and Sporting Classics now bring you Volume II, chock full of amazing stories and facts, a breathtaking color section filled with eye-catching whitetail art and nearly 400 stunning black-and-white photos. Buy Now