Lanford Monroe is one of those rare people…doing exactly what they set out to do when they were seven years old.

It is the matter of the voice. It comes out of the telephone like a cat, stretching. It is hard to believe we’ve never met.

The Artist.

“You really think so? Now folks down here say I’ve got a real northern accent,” Lanford Monroe says. “They say they know right away where I’m from … ”

Occasionally, it is true, a tight Connecticut inflection creeps in, and once or twice a flat South Dakota twang, but mostly, to my ear anyway, it is 22-karat Dixie. Or maybe that’s what I want her to sound like, to have her voice match my preconceptions of a painter whose work looks to have sprung from the pages of one of William Faulkner’s more well-adjusted stories.

But no. One by one, my illusions are blown to bits. Lanford Monroe is not irrevocably wedded to the South; in fact, she is starting to think of moving on. And no, she does not paint just darkly atmospheric Southern scenes; I ought to see her recent stuff from a trip to the Southwest, or her paintings of Bimini. Not Faulkneresque at all. And anyway, she did not move back south to Alabama for any reason more deep and mystic than to allow her daughter, Charlotte, to be close to her grandparents.

Get that Stephen Foster off the gramophone, Martha; it is time to find out about the real Lanford Monroe.

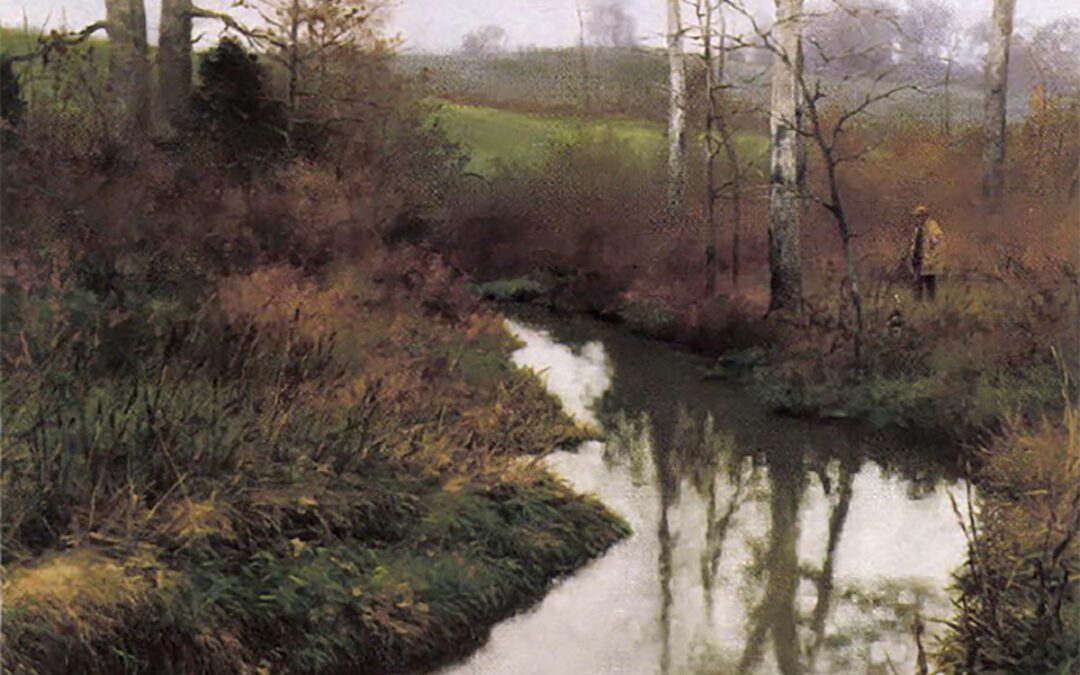

Pair of duck hunters in “Heading for the Swamp Blind.”

Lanford Monroe is one of those rare people you meet every so often that find themselves, in the prime of their lives, doing exactly what they set out to do when they were seven years old. She wanted to be a painter; she is a painter. She wanted to be a cowboy; she has been a cowboy. She wanted a small farm, and horses, and solitude, close to her family in Alabama, and she has all those things. Yet she is restless. You don’t expect to encounter wanderlust in a person whose dream has come true.

“It’s no big deal, I just think it might be time to move on. When I came here (to Athens, Alabama, four years ago) I was looking for solitude and I found it. This is definitely out of the mainstream. Now, I’m fee ling a little too removed. I need the input of other artists and new places, and the energy generated by an artistic community. Artists here are isolated. People who are interested in art don’t think you can really do it, really make it your life. It is something other people do, in other places.

“Where I came from, up in Connecticut, painting was the natural thing to do. Everybody I knew when I was young was doing exactly what they aspired to. It never, ever occurred to me to be anything else than an artist … and I started drawing real early….”

Monroe does not overstate. Her father is the celebrated artist and illustrator C. E. Monroe, whose work graced the covers of magazine after magazine in the 1950s; her mother is the well-known portrait artist, Betty Monroe. The family moved early to Bridgewater, Connecticut, where their neighbors were Bob Kuhn and John Clymer.

A red fox crossing “Carpender’s Hollow.”

Her father taught her, as she puts it, “about the woods, about painting, the whole bit.” She did her first commercial commission when she was six, a series of works for a Jenny Doll campaign, was paid for it, and paid her first percentage to an agent. Real life. At the age of six.

Unfortunately, real life intruded in other ways. The great magazine era was drawing to a close in the early 1960s and C. E. Monroe’s commissions dropped to a fraction. When Lanford was 14, her father moved back to his hometown of Huntsville, Alabama, where he took over the family printing business.

So much for the storybook existence.

Even so, life in the South was not bad. While her father was establishing a commercial art agency, filling in the rest of his time painting, hunting, and fishing, Lanford pursued her own interest in art. In between acting as her father’s bird dog on dove hunting expeditions, she studied the works of Ernest Thompson Seton and Bruno Liljefors, and ultimately found herself studying at the Ringling School of Art in Sarasota, Florida, the recipient of a Hallmark Scholarship in Fine Art.

“Trouble was, they were really modern-art oriented at Ringling. Not as much as other schools, but still more than I wanted. They did teach me a lot about drawing, though … “Monroe left without finishing, determined to go on her own, and paint what she wanted to paint.

Mule deer in “March Storm.”

Which was, to a great degree, wildlife – wildlife and landscapes, wildlife in landscapes.

“It was what I knew, what I grew up with, so it was a natural place to start,” she says.

But her pursuit of a serious career in art was interrupted by the opportunity to fulfill another childhood ambition -to be a cowgirl. She met, and married, a one-quarter Sioux Indian, foreman on a ranch outside Buffalo Gap, South Dakota. For Lanford Monroe, it seems, no sooner is one idyll shattered, than another comes along to take its place. She found herself, for four years, living a life that fireside dreams are made of, dreams which rarely include, alongside the romanticized ideal, the harsh realities of living without running water.

She rode, roped, rounded-up, branded, hunted, cooked on a voracious old woodstove, and walked through the snow past trapline pelts hanging on the barn on her way out to feed the chickens.

Painting took a back seat to married life on a ranch still nosing towards the 20th century, but not entirely. She painted, in watercolors mostly, and traded her landscapes to nearby ranchers for practical things like heifers and hogs.

There is a temptation to dwell upon this period in her life, but the truth is, its time is past. All that remain are the memory, some paintings, and her daughter Charlotte, now 11 but barely a year old when Lanford retraced her steps east to her parents’ home in Huntsville, Alabama.

“Vigil” depicts a cougar watching for prey high above Canyon de Chelly in Arizona.

Lanford returned to Alabama in search of seclusion, and finally found it on a ten-acre farm outside the town of Athens, in the tail-end of the Cumberland Mountains, an offshoot of the Appalachians. There, she and Charlotte live in a weathered cedar clapboard ‘saltbox’ house, classic New England look, big chimney with a huge stone fireplace on one side of the main room, and on the other a large window where she can look out and see no one else.

“It was a rough time in my life, and I thought a lot about where I wanted to live before I came back here,” she recalls. “Thought about going back to Connecticut. However, I had a totally wonderful childhood there, and if I went back, I would be in competition with my memories.

“I don’t think it could ever be as good as I remembered …”

Ensconced in Alabama, near her parents (both still active artists; her mother, Betty, has stopped taking portrait commissions, but still has three years work ahead of her with previous commitments), Lanford Monroe threw herself back into her first love, painting.

An exhibition of the American Impressionists, in Huntsville, changed the way she viewed painting — in particular, the works of William Merritt Chase and John Singer Sargent.

She abandoned watercolors, her previous medium of choice for outdoor work in favor of working directly in oils, in the field, and gradually focused on the two subjects for which she is best known: landscapes and wildlife.

It is not, of course, that simple.

“Clearing by Evening” reflects Lanford Monroe’s concern for documenting “a way of life that is rapidly being pressed farther and farther back as this area of the South becomes discovered by industry and the population.”

Lanford Monroe defies easy labels. In a way, she is a bit of a throwback, working in both sculpture and painting, a tradition that goes back to the Renaissance but is seen less and less frequently today. Her favorite subject for sculpture is the horse, since childhood one of her great loves; she has done a series of five bronze horses for the Franklin Mint, and has done three more on her own, in editions of 20. They sell for about $2,500.

“I find sculpture to be a good switch from painting. I don’t like to take vacations, because I have a need to keep producing. When I sculpt, it refreshes me, and I go back to painting with a new outlook.”

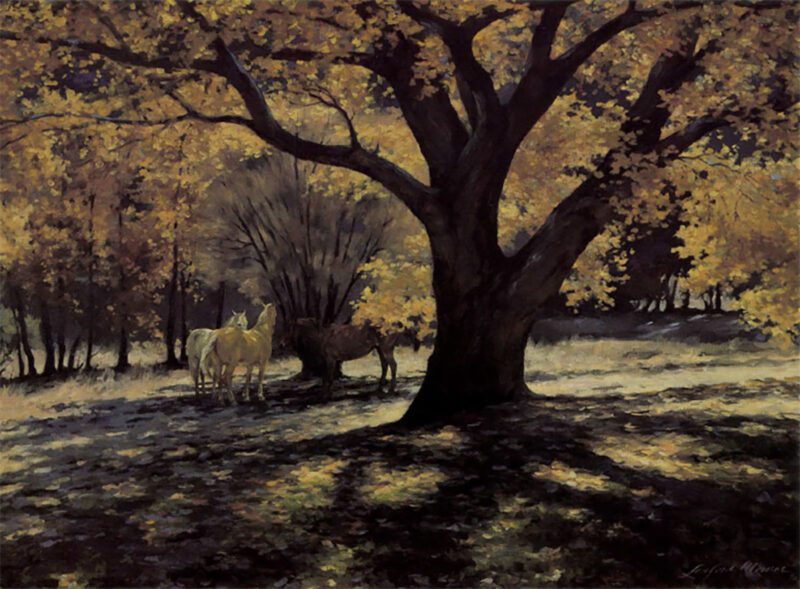

Monroe is also a noted painter of horses, and her work has been recognized by the American Academy of Equine Art. She now paints about half landscapes, with people and horses, and half with wildlife themes.

It has been noted that Lanford Monroe is far from the traditional “wildlife” artist, in that you frequently have to search her painting to find the bird or animal. In From The Wild, a Canadian wildlife art book published in 1986 by Summerhill Press, critic David Lank notes that Lanford Monroe and Canada’s George McLean, are pointing “to the future of wildlife painting.”

“Look at a Monroe,” Lank writes, “And the first thing you are likely to see is landscape. It takes a minute or two to find a living creature.”

“Palomino”

Monroe herself explains it this way: “You don’t paint a place, you paint how you feel about a place, incorporating the mood, memories, expectations – that place in time. To carry your thought to the viewer, the use of animals or man as a subject is of tremendous importance, not to balance the composition, but to balance the concept.

“A back pasture with a glimpse of a fox will become silent, alert with possibilities. You are an observer on untrespassed ground. That same pasture, with grazing horses or sleeping cattle, will become restful and calming.”

From The Wild was Monroe’s first appearance in a book; among the other 11 featured artists were Robert Bateman, Bob Kuhn, Stanley Meltzoff, and Roger Tory Peterson. Not bad company.

“I suspect that Bob Kuhn had a hand in that,” Monroe says. “Ever since I was a little girl, Bob has tried to help me — Bob and John Clymer — and I always try to drop in and see Bob and Libby when I’m up in New York.”

She is also taking her first, tentative step into the world of art prints, a medium which traditionally does not favor the soft, the introspective, the impressionistic, all of which define Lanford Monroe’s work.

Her first print, issued this year by the King Gallery in New York (she is also represented by Read-Stremmel in San Antonio), is called Backwater – Heron. It is a painting of such exquisite balance, it would probably hang on a wall without a hook; if the tiny heron was removed, it would tip slowly over on its side.

“This is really a trial for me, because I have worked in originals so long,” Monroe says. “I worried that prints are overdone at this point, but at the same time, I’m not that prolific a painter.

“I’ll do maybe 20 paintings a year…”

Why a heron, of all things, in a market which has always leaned toward game animals, game birds, and the more spectacular predators?

“I don’t know. Fred King particularly liked that painting, and he knows the market. We’ll see how it does.” Monroe paints now almost exclusively in oils (which sell, incidentally, for $6,000 to $9,000) and has become best known for her soft renderings of Southern scenes, subtle tones, subtle color changes, her landscapes given life with kingfishers, herons, raccoons. It has been said that she is “progressing” from wildlife art to landscape art (she hates both labels) and argues with the use of the word “progressing.”

“Progression denotes a move from one to another, leaving the first behind,” she wrote to me, feeling in the late-night, sleepless hours that her explanation on the telephone had been tongue-tied, incomplete. “In the case of painting, it’s more of a drift – exploring areas, becoming familiar with them, adding dimensions or honing them down to simpler forms.

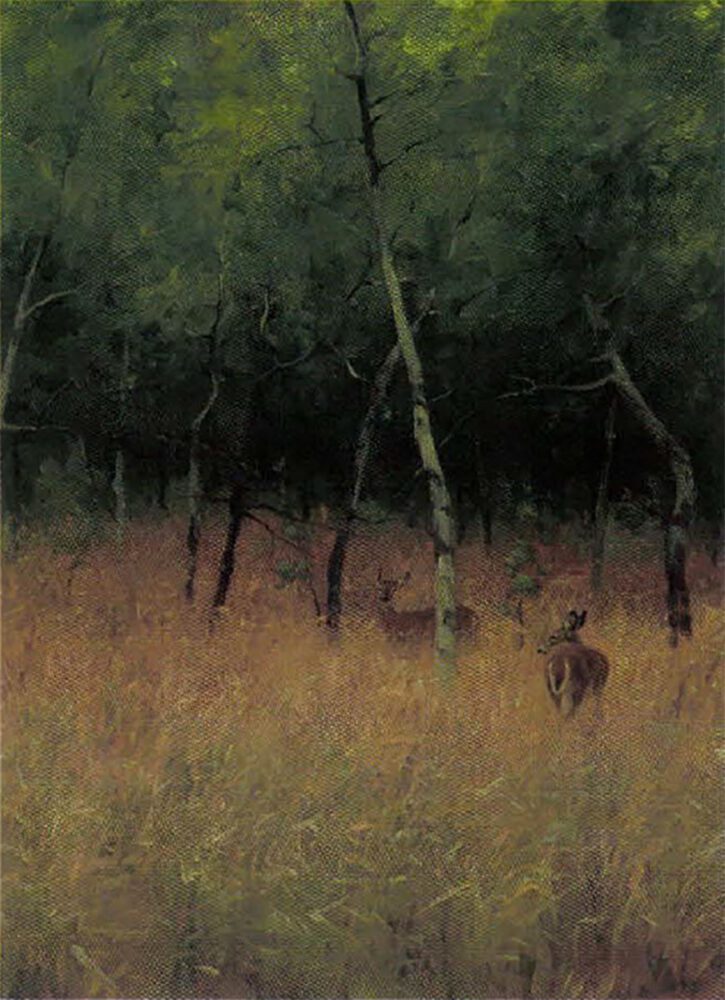

Colorado whitetails in “Aspen Ballet.”

“Wildlife painting is not something I’m leaving behind, I’m adding to it.

“As a painter, I don’t have a goal per se, other than technical achievement and to become a better painter. I’m not aiming for some finish, as much as recording my passage; not just where I am, but how and what I am.”

Where she is right now is northern Alabama. What she is, is one of North America’s most successful young artists, her reputation growing with each show, each publication. How she is … well, she’s restless, and she says it shows in her work.

“All the emphasis on rural farm scenes … Whether I started looking for them or just began seeing them, I don’t know,” she wrote. “Nor do I know if the intensity of my pursuit is because the scenes are leaving or because I am (not a morbid thought — just getting restless again).

“In either case, there is a need for me to do this now — to respond, to see. By painting it, I see it. I give to it something of me, my response and feelings toward it, and in return it becomes part of me, is mine, is not lost.”

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1988 September/October issue of Sporting Classics.

This work, which is an updated and revised combination of two venison cookbooks Casada wrote with his late wife, Ann, runs to 264 pages of recipes and a detailed index along with an additional 14 pages of narrative material on subjects such as how to handle your deer at every step from shot to pot, health information, and more. There are 282 recipes for venison along with well over a 100 more for sauces, marinades, toppings, and the like. There are dozens of toppings for burgers and other preparations as well. The seven chapters cover “Fancy Fixings,” “Ground Venison and Cubed Steak,” “Crockpot Cookery,” “Venison on the Grill,” “Soups and Stews,” “Forgotten Portions and Unusual Approaches,” and “Health-Smart Venison Cookery.” Buy Now

This work, which is an updated and revised combination of two venison cookbooks Casada wrote with his late wife, Ann, runs to 264 pages of recipes and a detailed index along with an additional 14 pages of narrative material on subjects such as how to handle your deer at every step from shot to pot, health information, and more. There are 282 recipes for venison along with well over a 100 more for sauces, marinades, toppings, and the like. There are dozens of toppings for burgers and other preparations as well. The seven chapters cover “Fancy Fixings,” “Ground Venison and Cubed Steak,” “Crockpot Cookery,” “Venison on the Grill,” “Soups and Stews,” “Forgotten Portions and Unusual Approaches,” and “Health-Smart Venison Cookery.” Buy Now