In 1912, in the southern part of the British Protectorate of East Africa (Kenya), a search party of two was coming to the end of its journey.

The men were ER. M. Shelley and Lord Stafford, the Duke of Sutherland. They had left the main safari and gone south to look for water, taking along a string of mules and a couple of native gun-bearers.

It was extremely hot and the men had been looking for water without success for a couple of days. They thought of sending a messenger back to get help from the main safari, but it was doubtful that even a native would survive the journey without water.

The men pressed on, hoping they would find water not too far ahead. The duke was becoming anxious, but the gun-bearers seemed confident water would be around the next corner. But sadly, as time went on, it became apparent that was not to be the case.

The duke was heir to one of Britain’s richest families. He had gone to Africa with his wife, Lady Stafford, who was well-liked by the native helpers and a superb horsewoman. During this era women were often looked upon as unfit for the rigors and dangers of safari life. In fact, only a few years earlier women were considered to be bad luck on safari, in the same way sailors thought women on board a ship would bring bad luck.

So Lady Stafford, a strong, attractive woman, was a rarity for that time, being able to outride and in some cases, outshoot most men.

As the two men pressed on through the heat, they saw in the distance a figure walking toward them. He was hard to make out in the shimmering heat. Shelley explained that if he carried a spear and shield, he would most likely be a Maasai. If he carried a bow, he would be a Wanderobo, a nomadic tribesman who hunted with poisoned arrows. Either way, their local knowledge of waterholes would be advantageous.

The native drew closer and the men saw that he carried a bow. “He must be ’Derobo,” said Shelley.

The native stopped and just stared at the two white men. Shelley greeted him in Swahili, but the man remained silent and looked somewhat threatening to the hunters. The gun-bearers started to look anxious. They too were waiting for a response.

Finally, the ’Derobo said, “Jumbo.”

Somewhat relieved, Shelley asked him if he knew where there was water. The man shook his head. Shelley thought he might be lying and would probably need some inducement. Shelley drew his knife and offered it to the man, handle first, telling the ’Derobo that if he could guide them to water, he would give him the knife and sheath.

The native agreed, and trotted ahead of the men. They headed farther south toward an area unknown to Shelley and the gun-bearers. After a while the native stopped and pointed to a deep gully. The men went to the edge of the ridge, dismounted and looked over to see a beautiful pool of clear water where they rested and ate lunch. Shelley wanted to head back and bring up Lady Stafford and the main safari. The duke said he would prefer to wait until morning and then return.

Something beyond their control would make the decision for them. Three lions sauntered down to the water to drink. The men stayed low and absolutely still until the lions had finished drinking and marched single file out of the gorge. The men had only a small amount of ammunition, certainly not enough to bring down all of the animals.

It was now dark and the hunters decided to make camp. They found some dry wood and built up a campfire for the night. They could hear lions grunting in the distance, then more grunts, close by in the darkness. The lions had returned.

Within an hour the men realized they were completely surrounded by lions. They piled more and more wood on the fire, hopefully to keep them at bay. It seems the lions had focused on the party’s mules.

The lions were moving in and Shelley thought the best course of action would be to set fire to the long grass to scare them away. He instructed everyone to carry a firebrand in one hand and a gun in the other, and then dash into the tall grass, setting fire to the grass as they ran. A brisk wind carried the fire toward the west, away from the men.

Every now and then they could see the lions watching the hunters on the other side of the blaze. They did not seem to be scared of the fire and were more hesitant to move off than hoped. Before long the flames had reached almost ten feet in height.

As they watched the lions moving in again, they pondered what to do next. It was then they spotted what appeared to be a lantern moving about three or four miles away. The men kept low and alert to the lions’ location as they watched the light draw nearer.

It seemed to take an eternity and the lions were going nowhere. In the distance there were now several lanterns moving toward them. It turned out to be Shelley’s main safari, and leading the way was Lady Stafford, followed by Duncan Lord, the duke’s gamekeeper from Scotland, the gun-bearers, askaris and syces.

The latter took care of the mules, while the askaris fended off the lions, which had decided it was time to leave with the arrival of so many people. The safari had seen the fire from seven miles away and with the help of the ’Derobo, they knew it was Shelley and the duke who were probably in trouble.

By noon the next day all the tents had been set up and everyone was having lunch. The lions had moved off, and Shelley along with the duke and duchess, were making plans for the days ahead.

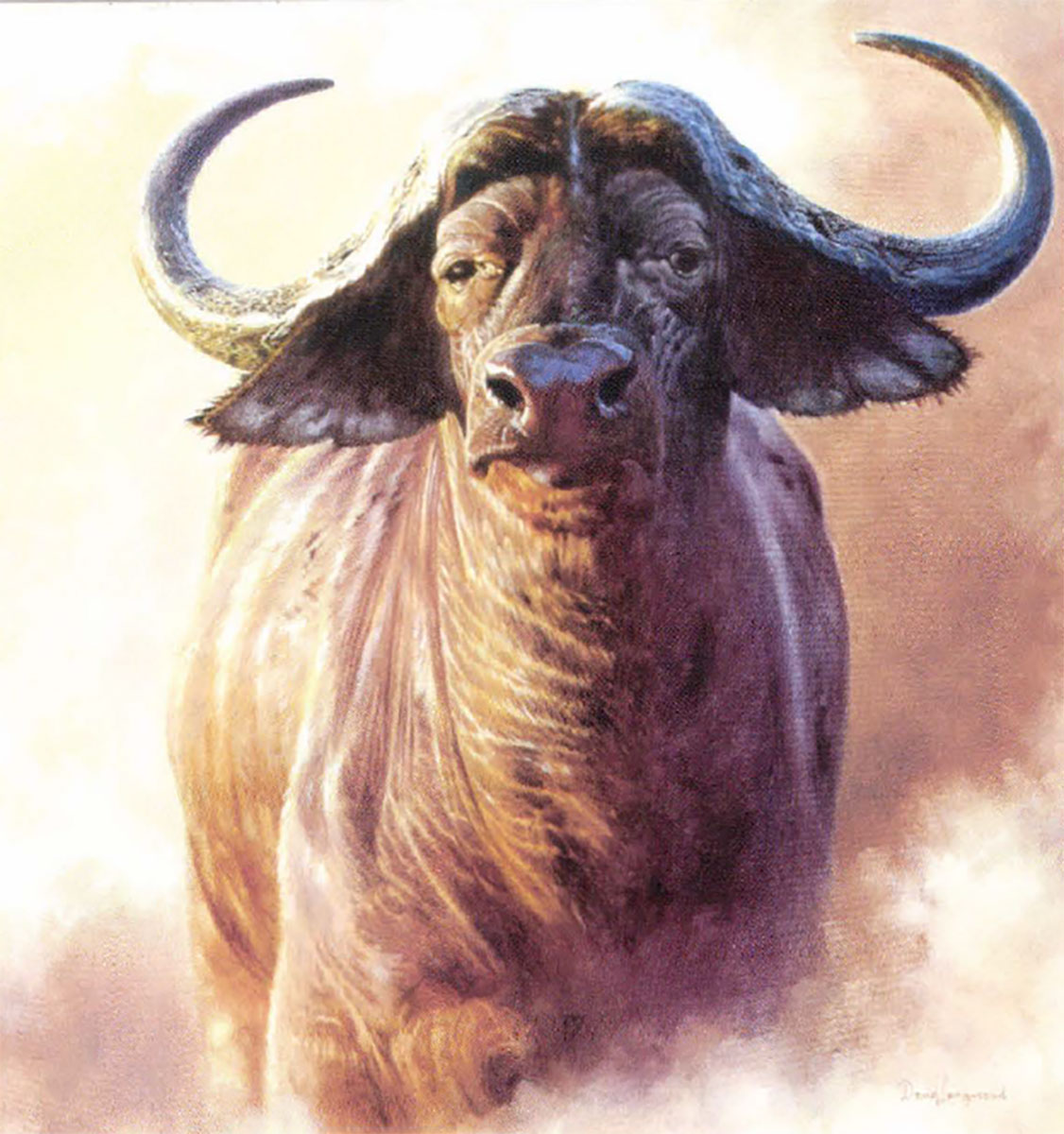

Lady to the Rescue is one of over 60 true stories with accompanying artwork in Campfire Tales by world-renowned wildlife artist John Seerey-Lester. Buy Now

Lady to the Rescue is one of over 60 true stories with accompanying artwork in Campfire Tales by world-renowned wildlife artist John Seerey-Lester. Buy Now