Only four years apart in their native Germany, Wilhelm Kuhnert and Carl Rungius would go on to become preeminent painters of the world’s big game.

For a short time in the late-1880s their trails crossed, the two young bulls setting out to make their ways in the world, bristling at every challenge, restless to possess the territories they would claim as their own. The younger was just beginning his studies at the Kunst Akademie (Academy of Art) in Berlin; the older, having learned all the instructors there could teach him, was poised to embark on his career. Four years apart in age, they were bound by a common goal: to become renowned painters of animals, musts the likes of which the world had never seen.

The older born in 1865, in Oppeln (now part of Poland), was named Wilhelm Kuhnert. The younger, born in 1869 in Rixdorf (now part of Berlin), was named Carl Rungius. Their impact on the intermingled worlds of sporting and natural history art, as it was then called, would be enormous; their influence on other artists, seminal. Today they are seen as giants, kings, the towering exemplars to whom every painter of big game animals must pay obeisance.

Carl Rungius’ Herd Bull, a 1906 oil-on-canvas.

The parallels between the two are striking. Both drew and painted incessantly from childhood on; both resisted intense pressure from their families to follow “conventional” careers, determined to pursue their artistic ambitions no matter how severe the obstacles or uncertain the rewards. Stubborn, disciplined and iron-willed, they drove themselves relentlessly whether in the studio or afield. And while both were slightly built, they had the lean, wiry physiques of marathon runners, with the same inexhaustible stamina. These were men who could go the distance. In their company you either kept up or were left behind.

They had this in common, too: They were both hunters. Not just average or even good hunters but extraordinary hunters, the kind who relished the challenge of stalking a particular animal for horns or even days across the most difficult terrain and in the face of the most brutal hardships; the kind who dismissed the cult of long-range riflery as little more than legalized assassination and prided themselves on going mano a mano, closing to a distance where they were not only assured of a quick, clean kill but experienced the animal as an intimate, knowable presence, not an abstraction. They saw through hunters’ eyes, painted from a hunter’s heart.

And while not friends, exactly, they seem to have been on friendly terms — although there was an undercurrent of rivalry. Nor was Kunhert above a bit of gamesmanship, the worldly graduate having a little fun at the expense of the grass-green underclassman. One day at the Berlin Zoo (where both men spent countless hours), Rungius was drawing a lion when Kuhnert — whose nickname, tellingly, was “Lion” – happened along. Appraising the sketch as if he were a Prussian officer squinting through his monocle, Kuhnert snorted, ‘Well, before one undertakes to draw a lion, one should Erst knowhow to draw.”

Kuhnert’s barb stung — but it tempered the steel in Rungius’ resolve to push himself to the limits, to Wring every drop of ability from his God-given potential.

A short time later their lives diverged geographically and, for all intents and purposes, permanently. Kuhnert departed for the first of his three extended expeditions to Africa in 1891 (when vast portions of the Dark Continent remained unexplored by Europeans); in 1894 Rungius set sail for North America where, other than a brief return to Germany in 1896-’97, he remained for the rest of his life. Although they were undoubtedly aware of one another’s “professional” accomplishments — Kuhnert’s Africa paintings were drawing attention by 1893, while Rungius’ illustrated accounts of big game hunting in the American West appeared in German sporting magazines in the early 1900s — there seems to be no evidence that they maintained a personal connection.

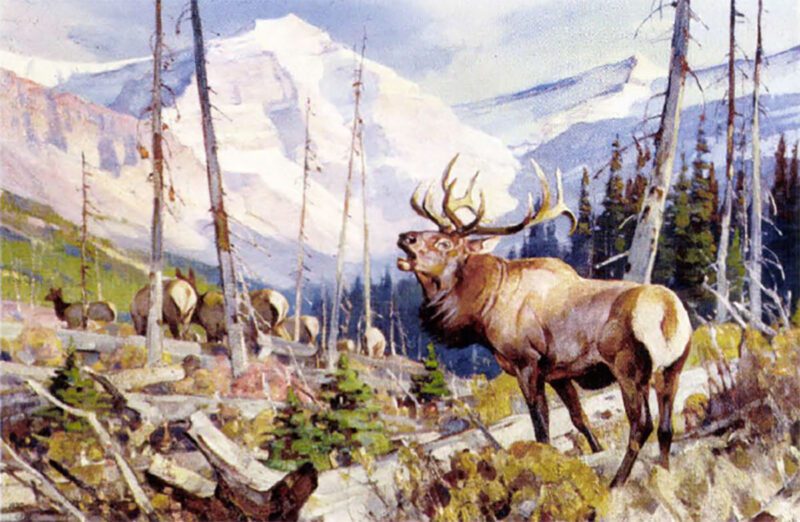

Rungius created American Elk in 1920, shortly before establishing a seasonal home in Banff, Alberta, where he researched and painted big game.

But while they worked different sides of the planet and focused their energies and talents on very different subjects, their careers stayed on parallel paths — and ended up perched atop the same summit. Ultimately, Wilhelm Kunhert and Carl Rungius surpassed anything that had been done before, setting new standards for the portrayal of wildlife, especially African and North American big game.

Kuhnert and Rungius did more than merely capture a believable likeness, more than simply depict their subjects in a lively, engaging manner. They did the most difficult thing of all: They revealed the animals’ essence, their defining characters, gave them personalities, even souls. They conjured their mystery and majesty, made them compelling, unforgettable.

And by placing their animals in authentic, fully realized environments — which had never been done before and was in fact contrary to what they’d been taught at Kunst Akademie — they invested their compositions with an extra measure of emotional power, a heightened sense of mood and place. When you view a Rungius painting of bighorn sheep or mountain goats, you feel your lungs expand with icy alpine air; when you look at a Kuhnert canvas of rhinos, elephants or buffalo, you taste the thick red dust -and perhaps the coppery tang of fear — on your tongue.

There is also this: While Rungius’ work is bathed in the light of the New World, Kuhnert’s is drenched in the blood of the Old.

The Africa Wilhelm Kuhnert first journeyed to in 1891 was wild beyond comprehension – and, by and large, it was still that way when he made his third and final expedition 20years later. (These hips were so extended, lasting nearly a year, that the usual term “safari” doesn’t seem to do them justice.) Kuhnert’s destination on each occasion was German East Africa, the boundaries of which had been hammered out with Britain in the mid-1880s — the high-water mark of European colonialism — and which encompassed modern-clay Rwanda, Burundi and Tasmania. Or, as it was known then, Tanganyika — less a name than an incantation, the distillation in a single word of the impenetrable mystery and irresistible obsession that is Africa.

Here was the soaring, cloud-wreathed massif of Kilimanjaro and the tawny enormity of the Serengeti Plain; here were native cultures little changed since the reign of the Pharaohs and people who’d never laid eyes on white skin. And here, of chief importance to the bedazzled Kuhnert and the mission he’d set for himself, was an abundance and diversity of wildlife such as he’d not dared imagine, herbivores and carnivores, the hoofed and the clawed, the homed and the tusked. There were the illimitable herds that stretched from horizon to horizon like living rivers; there were the solitary monarchs, imperturbable, unchallenged, moving beneath the thorn trees with the lordly assurance of the entitled.

There were the predators and the prey, the hunters and the hunted — and Kuhnert reveled in it. He ate it, drank it, breathed it, slept it, filling his days with stalking and sketching and simply observing, noting the habits and behaviors and interplay of the dozens of species he came in contact with. “Although the hunter in me has a difficult time overcoming the desire to shoot,” he once wrote, “the artist in me is stronger … ”

Single Lion – Kuhnert enjoyed working on huge canvases; the lion canvas measures nine feet wide.

In the 1995 book The Animal Art of Wilhelm Kuhnert, author Terry Wieland, a deeply knowledgeable student of African history, game and hunting, describes Kuhnert’s treks through the bush: “Kuhnert traveled on foot, followed by longlines of porters bearing his camp on their heads — his tents, camp furniture, clothing, food, his easels and paint boxes and canvases, clean, finished, and partly finished – his rifles and ammunition and hundreds of pounds of other paraphernalia. He crossed vast swamps, struggling through mire and areas choked with grass; he encountered beasts that walked, ran, Hew, crawled, swam, charged, bit, scratched and stung. He hunted and killed for meat, for trophies, for subject matter for his art.

“Through it all he painted, sketched and drew … Authentic Africa was about to burst upon the German art world, and it would never be the same again.”

Talk about shock and awe: One of Kuhnert’s early canvases depicted a lion devouring the beheaded remains of a native postman. The public got its first serious taste of his Africa paintings at the 1893 Berliner Art Exhibition, where his work stood out so conspicuously that he was awarded the exhibition’s Medal of Honor. It was an unheard-of achievement for a 28-year-old artist, but it was only the beginning.

Flushed by his success, Kuhnert hurled himself into a sustained frenzy of creativity. He is believed to have completed an astonishing 3,500 major artworks (most of them lost or destroyed, tragically, in World War II), along with another2,000 sketches and “incidental” pieces. He found time to many in 1894, but while his bride, Emilie, was young and pretty, there was a part of him that she could never reach, a need in him she could never satisfy. Africa had seduced him, become his mistress, his great, enduring passion. It gripped him like a disease, a raging fever, something ineradicable in the blood.

Shortly after his second trip to Tanganyika in 1905-’06 (during which Kuhnert was caught up in the bloody tide of the Maji Maji Uprising), Emilie took their young daughter Margarethe, and left him. As Kuhnert’s grandson Hansjorg Werner told Terry Wieland, “You must know that (my grandfather) lived for his art and for his hunting. He was away years at a time, leaving his wife at home in Germany. She was forced to sell his paintings in order to live …”

Kuhnert made his third trip to East Africa in 1911-’12. It proved to be his last one, as plans for a return were scuttled by World War I and the political upheavals that subsequently wracked Weimar Germany. Here married in 1913, and in 1916, with the war-mired in the fetid trenches of Belgium and France, visited what must have seemed like Eden: the Bialowies Forest in Poland, formerly the private game preserve of Czar Nicholas II of Russia. There, Kuhnert saw and painted the almost-extinct wisent, the European bison. But while his paintings of European game (of which he did a considerable number) are not without merit, they lack the conviction and raw emotive power that makes his African work so enthralling.

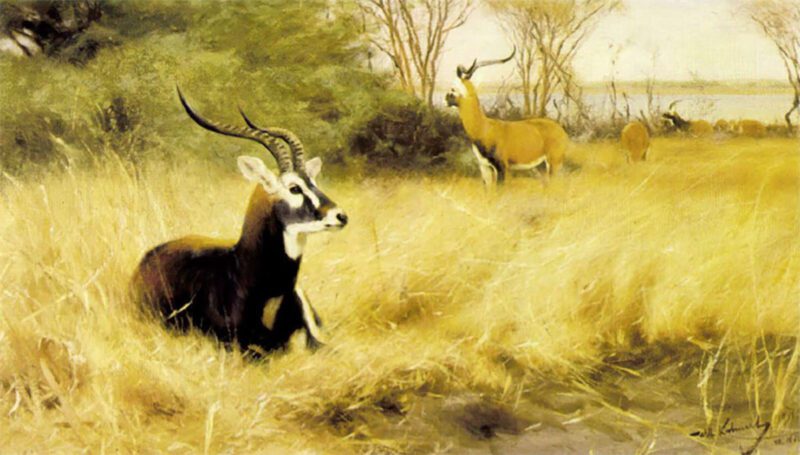

Gazelles (white-eared kobs)

Kuhnert’s second wife, Gerta, died in September 1925. Less than six months later, Kuhnert himself was dead at the age of 60. While the immediate cause was pneumonia, he had apparently been suffering for some time from an unspecified affliction. Revealingly, however, he was under the care of a doctor said to be a “specialist” in the treatment of tropical diseases. It was as if the fire ignited by Africa had finally burned him out, consumed him. As early as 1915, in a discomforting self-portrait entitled The Artist with Mixed Bag, the sense of burdened weariness is palpable; there is no hint of triumph, no suggestion of elation or even satisfaction. He signed his last letter to Margarethe, written 10 days before his death on February 11, 1926, “Your long-suffering father.”

But now his torments were over. And his spirit, released from its mortal coil, was free to seek what it longed for: the eternal embrace of Africa.

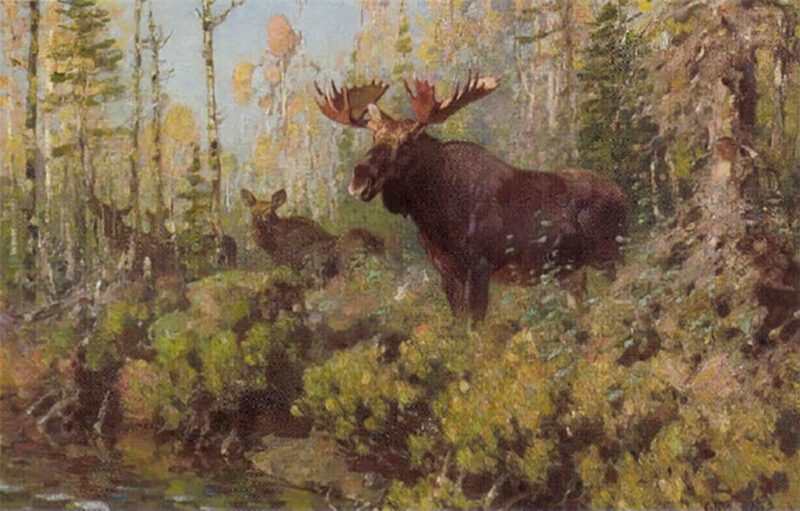

Carl Rungius was lauded as a painter of moose before he’d ever laid eyes on the living, breathing beast. His uncle Clemens Fulda — a German emigre who’d established a prosperous medical practice in New York City — invited him on a moose hunt in Maine, and in 1894, Rungius arrived in America with high hopes and great expectations. Their guide, however proved to know almost nothing about moose hunting — and just enough about woodcraft to keep them from getting hopelessly lost and/or starving to death. They managed to bag a couple of deer but didn’t even see a moose, much less shoot one.

It may have been the best thing that never happened to him. If Rungius had been successful, he in all likelihood would have returned to Germany on the next boat — and the course of his career would have been irrevocably altered. But his uncle, who knew how desperately his nephew wanted a moose, invited him to spend the year as the Fulda’s guest in order to by their luck again the following fall. He didn’t need to ask twice.

Determined to paint a moose even if he had no experience with the genuine article, in the winter of 1895, Rungius completed a life-sized head-and-shoulders portrait of a mighty bull, based on specimens he’d studied at the American Museum of Natural History and a local taxidermy studio. The piece was hanging in a Fifth Avenue gallery when William Hornaday, a leading figure in America’s budding conservation movement (and soon to become Director of the prestigious New York Zoological Society), saw it — and was literally stopped in his tracks.

“It looked,” Hornaday recalled, “as if a section with a wild animal in it had been cut out of the Maine woods and framed as an exhibit from the workshop of nature.”

Rungius’ love of the Canadian Rockies is evident in Bugling Bull.

Hornaday not only befriended Rungius, he became in effect his agent, getting him connected, introducing him to anyone and everyone who was in a position to further his career. The list reads like a Who’s Who of prominent sportsmen: magazine editors like George Bird Grinnell of Forest & Stream; explorers like Charles Sheldon (who persuaded Rungius to join his 1904 expedition to the Yukon); the social elite who comprised the memberships of the Camp Fire Club and the Boone & Crockett Club; even the “Bull Moose” himself, Theodore Roosevelt, who called one of Rungius’ canvases “the most spirited animal painting I have ever seen.”

About the same time he met Hornaday, Rungius met Ira Dodge, a Wyoming-based guide and outfitter, at a sports show in Madison Square Garden. The buckskin-clad Dodge could have stepped directly out of tile Wild West of Rungius’ imagination, and his tales of hunting antelope, elk, and “griz” (as translated by his German-speaking wife) so excited Rungius that he all but burst his skin. The Dodges were so charmed by his enthusiasm and sincerity, in fact, that they invited him to their ranch in the foothills of the Wind River range. Maine, Rungius decided, could wait.

In contrast to Kuhnert’s African expedition, which required a small army of porters and assorted “staff,” the American (and later Canadian) West afforded Rungius the exhilarating freedom to travel light and follow no agenda but his own. Resourceful, self-reliant and comfortable with horses, once he learned the lay of the land he preferred to go it alone.

“For years in Wyoming,” Rungius recalled, “I didn’t take a guide or companion – and of course I went to new places every time. I loved the solitude …

“I used to travel, with a saddlehorse and a pack-horse up into the hills about 25 miles from any habitation. And I’d stay for four or five weeks, often, until my work was finished or my provisions were exhausted. When the latter happened, I’d go down to the nearest ranch and lay in a new stock, and start out again with my horses.

“My pack consisted of just the barest necessities -bedding, clothing, and implements – as well as my painting and gunning paraphernalia. Then I had flow; bacon, tea, fried fruit, and a few other staples …Naturally, everything I had to eat, except the bread I made and the dried or salt things I took with me, was what I killed myself.”

The Family showcases how the artist immerses his animals in breathtaking mountain panoramas that conjure a sense of heroic majesty.

Rungius finally got his moose, ill the Green River Canyon south of the Dodge’s Box-R Ranch, in 1898.But it was in the early 1900s, when he made a number of trips to New Brunswick, that he developed his reputation as “the Rembrandt of the moose.” Among his admirers then was Frederic Remington, arguably the most celebrated American artist of the era. “This man Rungius knows our animals and he knows their backgrounds,” Remington observed, “and he paints it so it looks all right to me … ”

Following a protracted courtship, Rungius married his cousin, Louise Fulda, in 1907. The holder of a Master’s degree from Columbia and a fervent suffragette, her independence and strength of mind were a match for Rungius’. Although she sometimes chafed at his absences — and often said that she came fourth in his life, behind “painting, painting, and more painting” — she remained a devoted helpmate until her death in 1940.

In 1910, Rungius paid his first visit to the Canadian Rockies near Banff — and despite his affection for Wyoming and New Brunswick realized that in terms of his artistic goals and aesthetic sensibilities this country had it all. “For the first time,” he noted, “I felt strongly the urge to paint straight landscape for its own sake. Until then I had considered landscape only as a setting for big game animals. But the grandeur of the mountains with the marvelous atmospheric conditions in Alberta and consequent color effects changed all that … I felt at last that I had found the land which I had been seeking.”

In 1922, the Rungiuses established their seasonal home and studio, “The Paintbox,” in Banff. (Ken Carlson, one of Rungius’ artistic heirs, tells a wonderful story of his pilgrimage to Banff in1970, when Rungius’ old friends not only shared their memories but pressed treasured artifacts — brushes, a buffalo skull, even a wooden sign bearing Rungius’ name that had hung on a gate outside the Paintbox — into Carlson’s hands.) Rungius was at the peak of his powers then, painting with nerve and passion and boldness. Bob Kuhn, whose career was dawning when Rungius’ was in its twilight, uses the word “exciting” to describe his work in that period, roughly 1915-1940. His animals seethe with vitality, with throbbing, pulsing life; his landscapes, with their angular geometries and panoramic sweep, conjure a sense of heroic majesty, of exalted permanence. In such places do gods dwell.

Unlike the tortured Kuhnert, Rungius was, by all appearances, content. Of course, he had the benefit of longevity; perhaps if Kuhnert had been granted a longer life he would have mellowed, taming his demons (if not altogether exorcising them) and finding a kind of peace. While Louise’s death was a hard blow, Rungius refused to turn his back on life. He continued to paint — although his work gradually lost some of its vigor and freshness — and, for as long as he was able he continued to hunt. In 1950, he bagged a trophy bighorn ram and a respectable mountain goat — heady stuff for a sportsman of any age, much less one with 81 years on his boots.

Following a series of small strokes, Carl Rungius died in 1959, at the age of 90. He was in his studio, with a canvas on the easel, when he suffered his final collapse. His ashes were scattered in the high country above Banff, up where the bighorns and the mountain goats live.

Home on the hill, the old bull could rest.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2006 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures. Buy Now

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures. Buy Now