Wayne van Zwoll discusses the real “King of the Beasts”, the African Leopard and those who dedicated their lives to hunting them.

I shook his left hand. There was nothing below his right elbow. He was strong, an aging giant six-foot-five, with a raw-boned frame to carry the muscle. His eyes bore hardships endured in places that had broken lesser men. A man truly worthy of hunting the king of the beasts.

The big Belgian wouldn’t suffer small talk, so I gave him none.

“Have you been to Africa?” I nodded. Not “of course” or “often.” He had explored Africa, lived with the Pygmies in the Ituri Forest, killed a leopard with a knife. His eyes softened just a little.

October 24, 1955, Jean-Pierre Hallet was fishing in the shallows of Lake Tanganyika, dynamite in hand. A catch of herring like ndagala would feed a few starving people in the drought stricken Mosso region of Burundi. With his Bagoma companions, he guided a pirogue into a cove a rifle-shot off-shore. Igniting a fuse was the last thing he would do with two hands.

He saw the Bickford cord light up and hurled the charge – but too late. The faulty fuse ushered spark almost instantly to 200 grams of gelatin explosive. The blast blew off his right hand and threw him into the croc-infested water. His helpers, fearing implication in a white man’s death, paddled furiously to beach their craft and fled. Ears ringing and partially blinded in one eye, Hallet saw two crocodiles head his way, “scaly backs carving a wrinkled wake,” he would write later. He pressed his bleeding stump to his side and began a desperate crawl toward shore with his good arm. Seven more crocs converged, one “almost as large as a native dugout. He shot toward me like a ridged green torpedo; an instant later I heard … jaws snapping shut. Seconds later, another clack sounded near my right shoulder and I felt a crocodile pass behind me, his scutes scraping my back….”

A powerful man in the prime of life, Hallet would credit his survival to a change in body position as the crocs closed in. With remarkable presence of mind, he went from a crawl to a slower, upright dog-paddle. Vertical, he would not be so easily snatched by jaws designed to operate in a horizontal plane. A clever decision – but one demanding great courage, given his bleeding arm and throttled pace. Repeating the tale to me decades later, he reiterated his defense of the crocodile as a creature with natural cravings. “The beast has nothing against humans. It responds to hunger. As do we all.”

Hallet’s charitable view of crocs reflects the leanings of a naturalist who accepts killing for need, but questions sport hunting. He confirmed as much in his 1967 book, “Animal Kitabu,” where he shared insights on Africa’s big game. There he made a case for snatching the lion’s crown as King of Beasts and giving it to the leopard: “intelligent, coolly calculating, patient and extremely wary.”

A powerful cartridge isn’t needed for leopards; but a nimble double affords two quick shots in cover.

One day in January, 1957, Hallet was at the rear of his 16-man caravan winding through the bush between the Semliki River and the Ruwenzi Massif – the “Mountains of the Moon.” The kapita, or man in the lead, was clearing the trail with a machete when the second porter spied a big male leopard crouched in a tree. He shrieked. The entourage shed loads and scattered like marbles. Hallet dashed forward as the cat pounced, claws tearing at the porter who’d screamed.

With no weapon and only one hand, the powerful Belgian sprang upon the leopard from behind. “I passed my arms under his forequarters … partially dislocating his shoulders [by forcing] each humerus into the side of his neck. The stump of my right forearm was long enough to hook around his right front leg, and I locked the hold by gripping my right elbow with my hand [while scissoring] his hind legs with my own, forcing them stiffly and widely apart.”

The writhing cat weighed about half Hallet’s 250 pounds, but tossed him about as if he “were a mere toy.” He couldn’t last long “Kisu! Kisu!” he shouted. Knife! Knife! For long minutes, none of the terrified porters within sight of the battle dared leave his spot behind or in a tree. At last the kapita threw a crude, foot-long blade. It landed several feet from Hallet. Shifting his weight to pin one of the leopard’s forelegs, he caught the blade’s tip, almost lost it, then “just missed stabbing myself in the chest” before plunging the knife hilt-deep into the beast’s ribs. Exhausting minutes later, the great cat was still.

A powerful cartridge isn’t needed for leopards; but a nimble double affords two quick shots in cover.

Thoroughly spent, Hallet lay contemplating his fate had the leopard broken free. “He would have mauled and killed me, [then dragged my] cadaver into a dense thicket and torn out the entrails and buried them. Starting at the face and working his way down, he would have eaten rather daintily – unlike the lion who ploughs into the hindquarters and works his way up. Once he had polished off the nose, tongue, ears, heart, liver and lungs… he would have hauled the remainder aloft and stuffed it into a tree crotch.”

Panthera pardus occurs across Africa’s game fields, where the English name “leopard” and the Swahili “chui” apply. Spotted black-on-yellow around head, neck and legs, the cat typically has two black stripes across its lower throat. Black rosettes cover the torso; stripes mark the distal half of the tail, whose tip is white underneath. Black leopards, all but unheard of in Africa, are rare genetic variants elsewhere. A close look reveals the rosettes in the black coat. Kenneth Anderson, who hunted and wrote of leopards in India, surmised the black color phase occurs more often in “Malaya, Burma and Assam.” These cats are commonly called panthers, though Anderson used that term to describe the spotted leopard too. In his 1959 book, “The Black Panther of Sivanipalli,” he described the hunt for that cattle-killing beast, the only black leopard he’d ever seen.

On the trail of a Namibian leopard, Wayne used a 375 H&H bolt rifle with a 2.5x scope in cover like this.

Solitary and secretive, leopards are well-camouflaged and except in parks, seldom seen during the day. Males stake out territories approaching 100 square kilometers, which overlap female ranges about a third that size. Both sexes spray urine as a marker. The call of both resembles the sound of “a thin board being cut with a coarse saw.” It is heard most often evenings in the dry season.

After a 93- to 103-day gestation, the female gives birth to as many as six cubs, normally two or three – only one of which may reach maturity. She raises them without help from her mate. They open their eyes in a week, are weaned and killing by their sixth month. Self-sufficient soon thereafter, they stay with their mother for 18 months or so, are sexually active at two to four years of age. On average, litters come every two and a half years.

Physical size varies by region. Full-grown leopards in South Africa’s Cape are smaller than those in Zimbabwe, where males average just over 2 meters (nearly 7 feet) in length and weigh 60 to 71 kg (132 to 156 pounds). A 90-kg male is exceptionally heavy. Females are much lighter: 32 to 35 kg in Zimbabwe and 30 percent smaller farther south.

Hunters hang more than a leopard will eat in one visit so they can wait for the cat’s predicted return.

Nocturnal hunters, leopards hunt mainly by sight. Anderson’s contention that they have “little or no sense of smell,” however, might be contested. Typically they ambush prey with a short rush. Jumping astride and grabbing with fore-claws the neck and shoulders of large animals, they rip into ribs or loins with their hind claws while clamping their jaws on the throat or biting the base of the skull to kill. Pound for pound among the strongest of animals, the leopard can bring beasts twice its weight – big antelopes, young giraffes and cattle – into a tree, there to dine without disturbance from lions and other pests. Their main prey is smaller: springbok, impala and the young of antelopes like hartebeest. Leopards kill lesser game too: dik-diks, duikers, klipspringers, also young warthogs and small mammals from mice to dassies. They relish domestic goats. On the Kalahari, up to 30 percent of their scat has shown porcupine remains. Leopards feed on carrion well past onset of rot. Occasionally they take fruit and vegetables.

Professional hunters I’ve accompanied have baited leopards with a variety of animals, but a zebra haunch ranks high on the list. Wildebeest serves too. “You want to hang an item big enough to ensure the cat won’t polish it off in one sitting. That way, you needn’t sit on a bait until it’s been hit.” Hunting stock-killing leopards and man-eaters, hunters in the early 20th century often tethered goats. Left alone, a goat will bleat, effectively calling the cat. But a cow, ordinarily silent, held the size advantage. Anderson tied donkeys as bait to find the man-eating panther of the Yellagiri Hills. A kill was salvation for all remaining donkeys, as it yielded enough meat to bring the cat back to that carcass, into the hunter’s lap.

A lethal threat to baboons caught outside their troop, leopards evidently pose little hazard to other wild primates. Few leopards on record have attacked full-grown humans. Dogs enjoy no such immunity. In fact, leopards seem to relish their flesh. John Hunter, in his 1952 book “Hunter,” wrote that while “half a dozen little curs can hold the biggest of leopards up a tree,” a leopard will “go to any extremes to catch and kill a single dog,” even enticing a dog from jungle’s edge by lying down and, head to earth, twitching its tail as if it wished to play.

Like Hallet, Hunter put the leopard at the top of the roster of dangerous game. By far smallest of the “Big Five,” it is also the fastest, and hardest to see even at very close range. We humans are relatively frail creatures; a leopard’s teeth and talons, in a blur of blood-letting, can leave us shredded if not lifeless. A lion is also fast, but bigger, so easier to see and an easier target. Buffalo, rhino and elephant can kill on impact; but bush that conceals cats barely reaches their knees. While faster than they appear before they come, huge herbivores lack a feline’s rocket launch. Their mass can absorb bullets; but you needn’t be an exhibition shooter to hit it.

Fast open sights on an agile rifle excel on the trail. A scope helps with a careful shot from a blind.

Professional Hunter Don Heath, with whom I’ve hunted, told me that “in Zimbabwe, 80 percent of animal-inflicted injuries suffered by hunters are from leopards – mostly when hunting parties trail a wounded cat.” But elephants cause 80 percent of fatalities. “When they want to hide, leopards are almost invisible. A charge is always up close and unbelievably quick. A leopard needs very little time to hurt you badly; but unlike an elephant, it needs more time to kill you. If an elephant coming for blood reaches you, your odds of surviving are slim.”

Opinion differs on whether a leopard keeps ripping at his first target in a tracking party or jumps from one to another. “He wants to hurt everybody,” insists one PH. “A leopard with running gear intact and dentition in place will have all of you in tatters quicker than you can say ‘shoot the bloody thing!’ He bounces from one man to the next until he dies. That’s why many people have survived leopard attacks. The greatest danger is sepsis from the filth on teeth and claws. Disinfectant is your friend.”

John Hunter wrote of a leopard that burst from behind a boulder. “The creature simply whizzed through the air … a yellow flash of light.” He fired “as though my rifle were a shotgun.” The cat’s leap carried it 12 feet onto the client, where it expired. Another time, with Masai tracking a wounded leopard, Hunter heard a low growl just as the creature shot from the undergrowth “like a bullet from a gun.” One of the moran missed with his spear. “In an instant the leopard was on top of his shield, mauling him about the face….” As the man fell, spotted cyclone clinging to him, another moran stabbed at it. “Instantly the cat turned on him….” Down he went, the leopard’s claws a-blur ripping him open. Hunter jammed his rifle’s muzzle against the beast’s neck and ended the melee. Tending to the Masai, he was “astonished at the amount of damage [inflicted] in a matter of moments.”

Trailing a leopard into cover, stiff loads of buckshot in a short pump-gun like this Mossberg excel.

Hallet’s encounter with the leopard that leaped upon his porter is remarkable on two counts. The first is the attack, given this animal was uninjured and otherwise unprovoked. Hunter did note, however, that such a leopard in hiding is much more likely to spring when acknowledged – per the porter’s shriek. “[If] their eyes meet, the leopard is on him like a flash….The instant he sees a look of recognition…. He charges instantly.”

That Hallet survived hand-to-claw combat is darned near miraculous. Famously, naturalist Carl Akeley also killed a leopard unaided. Though a smaller animal (an 80-pound female) and hampered by Ackeley’s ill-aimed shot that broke a foot, she quickly minced his arm from wrist to shoulder. Then he managed to ram a fist down her throat. Using his knees to keep her down and crush ribs, he finished her with a knife.

Very rarely, leopards resort to hunting people. From 1959 to ’62 the man-eaters of Bhagalpur in India claimed an estimated 350 victims. As chilling was the record of a single feline whose depredations claimed at least 125 people. For eight years the man-eating leopard of Rudraprayag eluded traps, poison and sportsmen inspired by the challenge and government-sponsored rewards. The aging male cat was shot at last by Jim Corbett, celebrated for killing man-eating tigers in the Kumaon Division of India’s United Territories. The Rudraprayag leopard proved one of Corbett’s deadliest opponents.

They may eat in trees, but leopards lie up in rocky places with dense low cover. Tracking here is hard.

The Panar man-eater, by local body count even more lethal, was his first man-eating leopard. And nearly his last. It was truly a king among the beasts.

According to Corbett, no mention of man-eaters was made in Government records before 1905. It would appear, he wrote, “that until the advent of the Champawat tiger and the Panar leopard, man-eaters in Kumaon were unknown.” While hunting the tiger in 1907, he heard of the leopard, then credited with killing 400 people. Corbett was new to hunting such beasts, attributing his success with the Champawat tiger and, soon thereafter the Muktesar man-eater, to luck.

In April of 1910, in a remote patch of brush to which the Panar leopard had dragged four human kills in a month’s time, he tied two goats. The cat killed one. Corbett was loath to organize a beat in the thicket, lest the leopard, sensing the push, turn back and endanger the beaters. At thicket’s edge, he had his men strap 10- to 20-foot blackthorn shoots either side of a tree that jutted into an opening. A rotten branch afforded a make-shift seat. In part to add stability, “I gathered the shoots on either side … pressed between my arms and my body.”

Jim Corbett, known for hunting man-eating tigers, also killed the Panar and Rudraprayag leopards.

Settling in that evening, he listened to bird calls and the goat’s occasional bleat to keep abreast of events in the bush. He had no torch; his only shooting aid would be the white rag tied about the muzzles of his 12-bore shotgun. Presently he felt a tug on the blackthorn shoots held to his ribs. The man-eater! Ignoring the goat, then finding it could not climb over the thorns to Corbett, the cat was trying to unseat him. It almost did, pulling on the branches, then releasing them suddenly. In the dark its growls, short feet away, were unsettling, but also informative. “It was when he was silent that I was most terrified.” At last the cat gave up and killed the white goat, a pale smear in the night. Corbett took imperfect aim and fired.

Hearing the blast, men from the nearby village arrived with torches. Reluctantly Corbett agreed that they should help find the cat, but single-file behind him. They advanced at measured pace. Suddenly, from a shadow in the torch-light sprang the wounded leopard! His unarmed companions “turned as one man and bolted.” Fortunately for Corbett, they collided with each other. Burning torch splinters knocked to the ground flickered just long enough for him to kill the man-eater with a shot to the chest.

One by one the villagers crept back from the darkness. Soon they were celebrating, Corbett with them. But if not then, certainly later, his satisfaction was tempered. The Panar leopard was doing what it had been so perfectly equipped to do. It had thrived not because it was hateful or vindictive or cruel. It killed because it was hungry, and chose the most vulnerable prey

Corbett would pursue the Rudraprayag leopard off and on for more than two years, and later title one of his books after the cat. In memory he described it as “the best-hated and the most-feared animal in all of India, whose only crime … was that he had shed human blood … in order that he might live….”

Oddly enough, that view of leopards holds sway with other hunters who’ve barely escaped them.

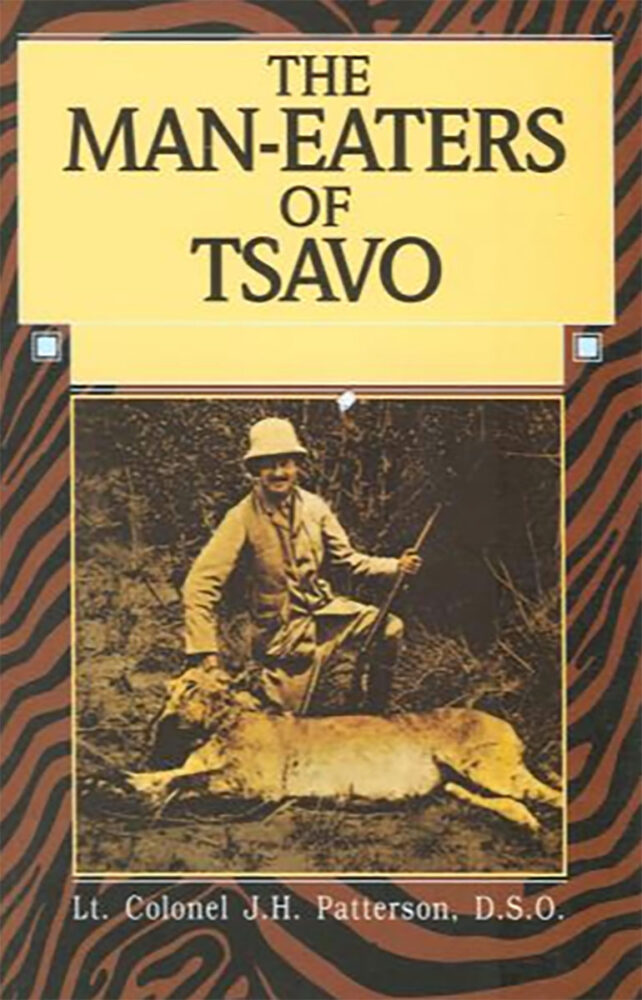

In 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed. Buy Now

In 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed. Buy Now