When in camp, he knew where he was. When he was on the blazed trails that led to the dead water, he knew where he was. When he left those, he was uneasy. I do not make the latter statement as a fact, but as a deduction. More correctly, I should have said: I think he would have been uneasy. As a matter of fact, he never gave himself any opportunity for uneasiness.

We slept in a log camp. It was my first moose hunt, you know, and people do sleep in log camps on their first trips, at least they do in the “personally conducted, everything-furnished-but-your- gun” kind of hunt.

Jud was a peculiar chap. Some things he always did, and some he always didn’t. There was no middle ground for him. Every morning at four o’clock, he would wake me. Someone had told him it was bad form to shake a sleeping patron, so he never did that. He always woke me by dropping tin pans on the floor. It was very dark at four o’clock in the morning, and I thought that if a bear happened to get into a log camp, about the first thing you would know of it would be hearing a tin pan drop. I intimated to Jud my distaste for his method, but it was no use. He had been dropping pans that way for years, and he probably always will.

Breakfast always consisted of oatmeal, a good, healthy, hearty food, one of the very best for a long tramp, but it’s abominable stuff.

Jud had his own way of cooking oatmeal, but he couldn’t seem to adjust the water to his theory. Most of it was squishy. When it wasn’t squishy, it stuck in your throat.

After breakfast, Jud would light his lantern and we would go down to the dead water. Going by his watch, every 20 minutes Jud would call; he was very careful about this. He said that if you called oftener, you were likely to frighten the moose, and if you didn’t call as often, the moose forgot the call. Something must have been wrong with his watch, for he couldn’t get the intervals right. Then he played the market on both sides but, every day, apparently the moose were frightened or forgot.

Shortly after sunrise on day one—when Jud first started calling—I sat bolt upright with my rifle held like a shotgun when you say “pull.” I stayed ready, for I had always read that when the caller called, a great moose would come crashing through the trees, and I wanted to be sure that he didn’t crash by before I could shoot. Jud rather aided this impression, for every time he called he would listen carefully and, then in a whisper, ask if I’d heard an answer. When a guide does that two or three times, you start to hear the answering calls of bull moose, just as plainly as the spoken word. So I heard almost as many answers as he did, and he always seemed pleased when I told him so.

Once the sun rose above the skyline, Jud’s interest always waned. At eight o’clock, we would get into the canoe and paddle to the other end of the dead water and hit the trail for camp.

Ours was one of a chain of camps. My agreement with the owner of the system required him to furnish the provisions, plain but plenty. He furnished two pounds of bacon and 40 pounds of oatmeal. We used up all the bacon within the first two days. No human being could have used up the oatmeal. Besides the oatmeal, there were many cans of evaporated cream, something I had never heard of before. It had an expensive sound, and that attracted me. I felt resentful that the provisioning of the camp was so insufficient. I determined that I would confine myself to evaporated cream and make the man sorry.

Each day I devoured three cans of evaporated cream, and I had bad indigestion long before it was gone. I may say that I was disappointed to learn later that the stuff retailed at seven cents a can.

After the indigestion set in, I refused to hear any more moose answers when Jud called. This was the first cloud on the horizon. We went down on the dead water one evening and, as usual, Jud called. I walked along the bank trying to catch a few trout. Jud whistled and I worked his way. His face showed excitement—this time a moose was surely coming! He had seen him across the barren!

I caught something of his excitement, but it was tempered with doubt. We got in the canoe to cross the dead water. When we reached the other side, I got out first and tried to pull the canoe ashore, looking ahead all the time for the moose. The canoe stuck. I pulled harder. Still it stuck, then I pulled vengefully. It stuck for a moment, then it shot up on shore. As it did, I heard a mighty plunge behind me—it was Jud.

He usually balanced himself with the paddle, but not this time. Only his head was out of the water; his cheeks were puffed out, except now and then when he whispered something I couldn’t make out. His eyes were wide and rolling, and there was an expression in them as if he were observing the manifold wonders of Nature for the first time and found them altogether different from his anticipations.

Of course, I was sorry for Jud. I knew the water was cold— nobody likes to get wet up to the neck. I was very, very sorry, but all the same he looked funny. The more I tried to behave with becoming consideration, the funnier he seemed. Finally, I gave it up and laughed. This pained Jud, and he looked funnier pained than he did when he was just wet. I laughed more—I laughed improperly and scandalously. Then I stopped.

I told Jud that laughing like that was a family misfortune, that I was sensitive on the subject, and hoped he wouldn’t tell any of the others when we got back to the main camp, because they might think it strange. He said that he wouldn’t tell, and a friendly feeling was restored.

Then he began to call. He always weaved his body when he called, and at every weave, his high moccasins would make sucky noises and the water would run out of the top. Then I began again. I stuffed my sweater in my mouth, but it wasn’t any use. Jud told the other guides afterward that when I broke out laughing the moose was within 30 feet of us.

On the morning of our last day, we took a carefully bushed trail to another camp about six miles away. This camp was also abundantly stocked with oatmeal. Also a skunk lived under it. It was almost like being in Russia; you never knew when it was going off. The skunk behaved with perfect propriety, however.

There was a lake near this camp. Moose sign was very plentiful, but someone had occupied the camp before we got there. On the edge of the lake was the carcass of a large bull, and it was rather bad when the wind blew that way. We were on the edge of the lake one evening watching a cow and a calf nearby. The cow was feeding, but the calf was on the alert. He was constantly looking toward the woods and the hair on his back was erect. It was very apparent that a bull was there.

While we were waiting for the bull to come out, Jud nudged me and pointed across the lake. A she-bear and her cub were walking up the shore toward the carcass, which was at the head of the lake. We were afraid to move. The moose was probably not more than a hundred yards away and, if we moved, we would be certain to frighten him. The bears were too far away for anything but a chance shot. There was nothing to do but wait. I had an excellent pair of field-glasses, and with them I was able to follow every move they made.

The cub was a frolicsome little chap, but the old female was a strict Puritan. For the most part, the cub romped along behind his mother, but several times he ranged alongside. When he did so, she faced about, sat bolt upright on her hams, and seemed to admonish him to cultivate a habit of more repose—he, in the meantime, regarding her with mingled respect and impudence.

The second time this occurred, the cub toddled along for some yards with much gravity, while the mother at times looked over her shoulder with suspicious commendation. But the pace was much too slow and devoid of incident for the cub, and he began his romp again, now and then approaching, but not reaching, the prohibited zone.

Then he made an error—he tried to pass his dam. As he did so, she gave him a slap that sent him spinning to the rear. And so I watched them till they rounded the point and disappeared. Then Jud called. The cow moose waited a moment with her ears erect, still chewing her cud, but with markedly less appetite; then, she solemnly started for the woods, the calf willingly following.

And so I missed my only chance to get a bear.

Jud and I remained at the camp for four more days. He called most of the time, but nothing happened.

I was rather glad when Jud lost the key to his watch the morning we started along another bushed trail to still another oatmeal station. He was so wrapped up in his time intervals that I felt certain we had reached the end of his calling season. I was not entirely persuaded that Jud was a good caller. The books I had read insisted that the caller must be a good one.

I mentioned this to Jud while we were walking to our next camp. He said the books were right, but he had learned to call from his brother, and that everybody in New Brunswick knew that his brother could call a bull moose away from a cow any time, and he could do the same—if his watch was right. He silenced me.

Our last camp was just like the others. We went morning and evening to the dead water for three more dreary days. I had given up trying to get Jud off the trail. So there was nothing for it but nerve-trying repetition. Four a.m., pans fell; 4:30 a. m., oatmeal; 4:40, the trail, and so on, and so on. We were in a good moose country, but the habits of the moose were as regular as our own. They, however, began their habits after we began ours. I reasoned that we would never see one unless we introduced some variety.

It had been an article of faith with Jud that smoking was fatal to success—that day I smoked. Jud always said “Sh’h’h” when I spoke above a whisper. He spent most of his time hissing that day. The air was freezing, so I built a fire. Having done everything that ought not to be done, I picked up the birchbark call and announced that I was going to give it a try. Jud said that would dispose of our last chance. He had heard me call before.

But this day was my own. This day was to be different from any other day. My call was to be different from any other call. I began all right, but my throat tickled, and I coughed into the caller. It sounded badly, but not enough to justify the look of agony on Jud’s face. Then I laughed into the call, and the result was awful. I had no idea that a simple little cornucopia of birchbark could emit such an ungodly bray.

Jud’s mind was usually slow and his utterance sedate, but now he had me fairly on the defensive. He developed a facility for profanity that was a revelation. I admit that before that time, I had thought that Jud was—well, that his intellect was clouded. But now it was apparent that Jud had also formed a similar opinion of me, and I am bound to say he expressed it with forceful particularity. When he had said absolutely everything there was to say, a deep silence fell.

But the silence was not prolonged. From the ridges across the dead water came sounds that instantly closed a treaty of peace between Jud and myself.

“It’s a moose,” said Jud. “Why, he’s coming . . . God knows, but he certainly is coming!”

Something was coming. There could be no doubt of that. The sound of breaking branches indicated that whatever was on the way was eager to arrive. Soon we could see the alders waving on the flat across the dead water.

Without a moment’s hesitation, a bull smashed his way through and rushed out in plain view on the opposite bank, not a hundred feet away. He stood there looking across the dead water, and a vicious-looking brute he was; the long hair on his back was erect and the little piggish eyes glared angrily. Plainly he was not there for love’s dalliance. He was there looking for trouble. He had evidently misconstrued my unfortunate call as a mortal insult, calling for instant resentment, and he was there on that business.

I raised my rifle very slowly, but my heart was pounding so that the white bead of my front sight traveled in figure eights all over his body—this wouldn’t do. Then he began to horn an alder bush. My nerve steadied a bit as I watched him. Then the white bead bore steadily just behind his fore shoulder and I fired. He didn’t fall.

He stiffened in his tracks, raised his head in what must have been a muscular spasm—but it looked like a voiceless farewell to the sun and the mountains. There was no anger now. He was just a stricken thing that waited in that rigid pose for death. Then he fell as a tree falls.

There was nothing but remorse in my heart when I stood beside him. I had traveled a thousand miles to accomplish this thing. I thought it would bring exaltation with it, but it wasn’t a fine thing; it was a wicked thing. Of course I got over it—we all do, but I never have been quite easy in my mind as to whether it was well to get over it.

After it was all over, Jud begged my pardon. He said his brother couldn’t have issued a better challenge call. He said he didn’t recognize it at first, and he wanted me to do it again so he could learn it. The fact that the watch was not needed for the challenge call fascinated him. By the time the first slice of liver was sizzling in the pan, we were good friends again.

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the July, 1912 issue of Outing magazine.

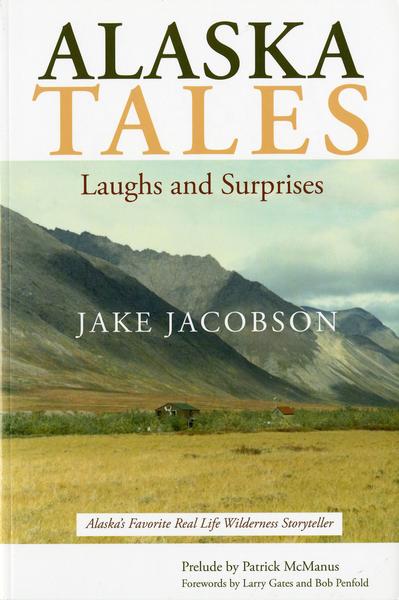

You should buy this book. It will make you laugh. It is full of stories you’ll want to read again, and again. You’ll tell your friends about it. Thinking about it will make you smile during boring meetings. People will wonder what you are up to. On a bad day, when you’ve screwed up at work, your wife is mad at you, and the kids are sick, this book will give you half an hour’s respite. It will take you to a place of adventure, danger, and humor, all woven together by one larger than life character. I had to get all that down fast, because it’s important. I’m not a writer, and I don’t know how long I can hold your attention.

You should buy this book. It will make you laugh. It is full of stories you’ll want to read again, and again. You’ll tell your friends about it. Thinking about it will make you smile during boring meetings. People will wonder what you are up to. On a bad day, when you’ve screwed up at work, your wife is mad at you, and the kids are sick, this book will give you half an hour’s respite. It will take you to a place of adventure, danger, and humor, all woven together by one larger than life character. I had to get all that down fast, because it’s important. I’m not a writer, and I don’t know how long I can hold your attention.

Dr. Larry GatesThe stories in this collection are true. In some instances, the names have been changed to protect the innocent and the not so guiltless.

With most days of the past forty-seven years spent in Alaska, the thirty-six stories in this collection are connected primarily with Jake’s guiding activities in the Great Land. These stories were selected for their humorous content.

This selection of tales is trivial, eclectic, and of minimal redeeming value. But there may be some valuable bits of information, if one looks for them. These stories attempt to entertain readers, to give them a giggle, or at least a wry smirk. Buy Now