Lying there half awake, slipping in and out of dreams punctuated by huge tarpon leaping and throwing hooks, I thought I heard the world’s worst choir. It wasn’t until I came fully awake that I realized it was no dream. A troupe of Pentecostal converts was making its way through the village, singing a gospel song with strong Creole overtones. There’s nothing like a 3 a.m. wakeup call in a Moskito Indian village on Nicaragua’s north coast to make you think you’ve seen and heard everything.

My fishing buddy John Helsper and I were staying in what we jokingly referred to as the “Karawalla Hilton,” a slap-dash bare, wooden shack that served as the village of Karawalla’s only guest lodging. It’s definitely not a place most people would care to visit. The lodging is poor at best, the food is strange, the water is undrinkable and a good night’s sleep is almost impossible. The few Americans who visit Karawalla are typically missionaries or tarpon fanatics, and John and I weren’t there to harvest souls.

The lagoons, canals and rivers near Karawalla teem with what I believe to be the world’s largest tarpon. Better yet, they’re not sophisticated tarpon. In a busy year perhaps 15 anglers venture to this wilderness, and as a result, the local tarpon eagerly snap at flies and lures.

My journey to Karawalla began with an Internet search for remote tarpon opportunities. I was not interested in the crowds found in Florida, and I knew that pollution has muddied Costa Rica’s best tarpon rivers. Randy Poteet’s Rumble in the Jungle web page immediately caught my eye. His site was full of photos of huge tarpon and trophy class snook, all caught in a wilderness jungle setting. After chatting with Poteet on the telephone a few times, I was convinced that he offered exactly what I was looking for. A few months later John and I were headed to Nicaragua.

Native children gather at the village meat shop where chunks of fresh sea turtle are displayed in their shells.

Poteet met us at the tiny airport in Bluefields on the Caribbean side of Nicaragua. The drive to Casa Rosa Lodge, named after Poteet’s wife, Rosa, wound through the hardscrabble streets of Bluefield. Along the way, Poteet – a self-proclaimed good ’ol boy from Tennessee – had us cracking up with comments such as: “You ain’t gonna find no good fishing anywhere’s you can get to from a Holiday Inn.” He said the rivers and estuaries near Bluefield usually provided good tarpon and snook fishing, but the abnormally long rainy season had the local rivers running high and dirty, and as a result, tarpon were scarce.

Crap, I thought to myself, we came 3,000 miles only to hear a variation on the old you-should-have-been-here-yesterday story. But that wasn’t the case. All Poteet was doing was letting us know that we might have to travel a bit farther to find the type of tarpon fishing most only dream of.

Poteet said the best tarpon opportunities were about 60 miles north in the rivers near the native village of Karawalla. He asked if we were up for a three-hour ride in an open panga, a few nights’ stay in a jungle village and some very basic meals. Before the words were even out of his mouth, John and I chimed in unison with an emphatic “Hell yes!” It was Poteet’s warning, however, that gave us both pause: “This ain’t a trip for sissies,” he said.

At daybreak the next day John and I, along with our guide Marco, piled our gear and three 25-gallon barrels of gas into a 26-foot panga and headed north through an intricate network of waterways that led through Pearl Lagoon to Karawalla. Along the way we encountered several rainsqualls, but to call what we experienced rain, is like calling Mike Tyson a bit unsophisticated. Often the rain came so hard that Marco had to slow to see where he was going. The driving rain was painful, even through our raincoats. Poteet’s warning was accurate so far.

After almost three hours of winding through pristine jungle and huge lagoons, Marco entered a narrow pass that opened into a spectacularly lovely 400-acre expanse, misnamed Evil Lagoon. It was mirror smooth with lush jungle reflected along the shore. Immediately we saw a tarpon roll, then another, then a school of four or five. The lagoon was simply stuffed with fish ranging from 50 to 250 pounds.

John had a lifelong goal of landing a tarpon on a fly rod and for more than an hour he fruitlessly cast to rolling fish. It almost seemed like they were teasing him. As soon as he would cast to a fish on his left, another would roll on his right. Eventually, the tropic heat and the strain of casting a 12-weight were too much, so we began trolling flies.

On our second circle around the lagoon, John’s rod slammed down hard. He responded with a hard hook-set and watched in frustration as his first tarpon, a fish we estimated at 180 pounds, threw the fly. In the next hour we jumped four more tarpon. I had one on for perhaps a minute, and John missed two other chances. So far the score was tarpon 5, anglers 0.

When the bite in the lagoon died off, Marco took us to his favorite river. A quick run across a shallow bay brought us to the Kurinwas, a large, slow-moving, tannin-stained river where tarpon were rolling regularly.

The next few hours passed in a blur of jumped tarpon and hooked tarpon, though rarely a landed tarpon. John achieved his goal of a tarpon on the fly, but it was small, and we both lost fish in the 200-pound class.

With dusk rapidly approaching we decided to find our lodging, and a 20-minute ride took us to Karawalla, our home for the next four days.

When our panga reached the city, a small group of shy but friendly natives greeted us. Marco spoke to a burly teenager and commissioned him to haul our gear to the hotel. The stroll up the worn pathway revealed a village right out of National Geographic. The town of 500 had no roads since there were no automobiles. The houses were built from hardwood planks and scattered in an almost random pattern. Most were brightly painted, and all were shockingly small. Most had electricity, but Marco told us the town generator ran only from 6 to 11 p.m.

Our hotel was a two-story bare wood structure with a few eight-by-ten rooms. There were no furnishings other than a bed and mosquito netting, and gaps in the boards made it easy to see into the adjacent rooms.

Once unpacked, we walked over to the home of one of the wealthier villagers who had agreed to feed us for $5 per meal. Our first night’s dinner was fried sea turtle with rice and beans. We found the turtle tasty, but tough.

The next morning, after a meal of turtle liver, fried eggs and the ubiquitous rice and beans, we headed back to the Kurinwas, but before were reached our destination we saw a significant number of tarpon rolling in a channel leading to the river. We stopped and began trolling flies, and by day’s end we each had landed tarpon in excess of 150 pounds, with one estimated at 200.

We ended up spending most of the next three days fishing the canal. The shore was lined with small subsistence farms, mostly beans and bananas. By trolling up and down the canal dozens of times, we hooked so many tarpon we lost count and more than a dozen snook and lots of jacks.

Just a few hours before dark on our last day, we decided to fish with plugs in hopes of catching a few snook to bring to the villagers. (We had developed the habit of keeping all of our snook and jacks to give to the very appreciative villagers. Once they learned we had fish to give away, a large crowd developed every evening to greet us.)

American angler Ryley Fee duels a feisty tarpon as it catapults from Kurinwas, a sprawling, tannin-stained river with countless 200-pound fish.

John was fishing a deep-diving plug when he hooked what at first he thought was the bottom. When he yanked hard on the rod to free his plug, the “bottom” began slowly swimming away. John began the tortuous job of winching his leviathan to the surface. It took more than an hour before we saw his fish and when we did, we were dumbfounded. It was a goliath grouper of more than 300 pounds. It took three of us to wrestle the huge fish into the boat, and by the time the battle was over, it was well after dark.

Our faithful retinue was waiting when we got back to Karawalla, and when the locals saw our catch, an excited murmur raced through the crowd. Soon two husky men with machetes appeared, and without asking our permission, they scaled, cleaned, butchered and distributed the mammoth fish to the community. Almost everyone on Karawalla had grouper for dinner that night, including John and I.

Guide Marco Torrez strains to lift a 150-pounder, average size in the Evil Lagoon.

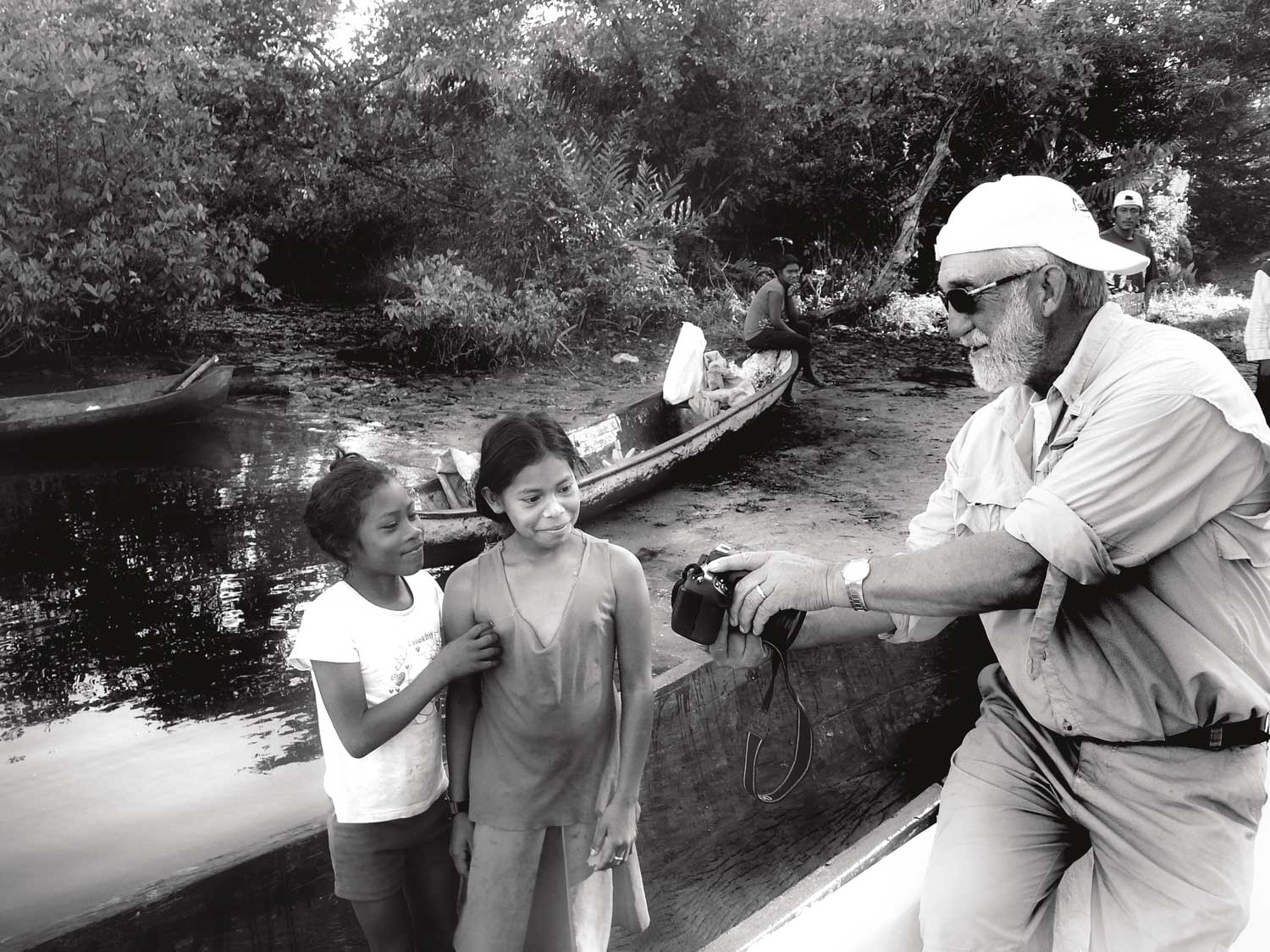

Every day in Karawalla was a joy; watching the village children look at their photos for the first time on my digital camera was a real treat. Eating the local food, while not always a treat, was interesting, and watching the flow of daily life in a Moskito village was fascinating. The nights, however, were another matter.

The village is simply awash with cows, horses, chickens, ducks and a bazillion mongrel dogs that roam the village at will. As dusk falls the cows moo, the chickens crow, the horses whinny and the dogs bark incessantly. Then there are the singers.

Missionaries representing Pentecostal, Anglican, and Moravian and Catholic churches have established churches in Karawalla. It seems that each church is determined to have its choir sing longer and louder than the others. Most stop before 10 p.m., but for reasons I do not understand, the Pentecostals begin singing again around 3 a.m., hence my strange dream.

In spite of the fact that sleep is nearly impossible in Karawalla, I am already dreaming of my return. I am more than willing to put up with poor food, sleepless nights and showering in unheated, undrinkable water for another shot at those huge, uneducated tarpon. But next year I will be sure to pack my earplugs.

If You Want to Go:

Managua is a three-hour flight from Houston. Those who can reach Houston before 10 a.m. can usually make connections all the way to Bluefield the same day. Those who arrive later will need to overnight in Managua. Our hotel, the Camino Real, was less than a mile from the airport. In the morning we were picked up and taken to the airport for the one-hour flight to Bluefields. It was simple, fast and absolutely stress-free.

Rumble in the Jungle is open year-round. Excellent freshwater and blue-water fishing can be had any month of the year. The only real question is how far you may need to run to find the fish. If the seas are rough, blue-water fishing will be off the menu. The rainy season typically begins in May and lasts through January. For those who wish to experience the jungle without the hardships of actually staying there, the lodge will run you up and back on a one-day trip.

Call Randy or Rosa at (912) 275-5485, email them at Randyrosa97@yahoo.com or visit www.rumbleinthejungle.net.

Fishing Gear:

All necessary tackle is provided, but if you want to bring your own rods, make sure they are rated for 20- to 40-pound line for tarpon and 15- to 25-pound for snook. Fly rods for tarpon should be 12- or 13-weight, and the reel must have at least 200 yards of backing. For snook, a 9-weight would be perfect. Any high-quality bait caster with a capacity of at least 200 yards of 30-pound line and a strong, smooth drag will do. As for line, 20- to 30-pound mono is a great choice.

Any minnow imitation in the 2- to 4-inch range will work. Smaller flies seemed to work better than the larger ones. For lures, bring Castaic swim baits, Yo Zuri Crystal minnows and Mann’s Stretch lures. Best colors were red and white; perch patterns, both in red and white, worked great. Bring a selection of surface lures and divers.