The rains were gone but the rivers were still swollen. He looked on in amazement as the men calmly walked into the river, each man carrying a big elephant tusk across his shoulder.

As they neared the middle of the river, they continued to walk until one by one they were completely submerged. They would disappear beneath the surface for only a few yards, but it was impressive considering none of them could swim.

Bell was in Bukora in the Karamojans, now Uganda, on his way back from hunting elephants in a most inhospitable place for visiting white hunters. The region was dangerous, not only because of its rogue elephants, but the natives who were intolerant of strangers. Still, Bell had managed to come through his safari unharmed, perhaps by good management, but more likely by sheer good luck.

Early in the expedition he had camped in the Bukora area, having just moved from Mani-Mani. Bell was cautious at the beginning, unsure as to how he’d be received by the locals. Gradually, more and more natives came to visit his camp and he was hopeful that he could put a safari together.

Bell’s guns were of great interest to the natives, who were keen to follow him as he hunted for meat. They were fascinated with what they called the bom-bom, his Mauser pistol, and the thing that went bing! bing!, bing!, Bell’s ten-shot .303 rifle.

The Bukora natives and the Kumamma, their feuding neighbors, soon learned to respect the “Redman” (a white man turned red by the sun) and his weapons. Bell, in turn, treated the locals with respect.

One day a Bukora youth came to camp saying he’d just returned from “no man’s land” where he’d been looking for Kumamma to assess their strength. He had found no evidence of his enemy, but he had seen plenty of elephants.

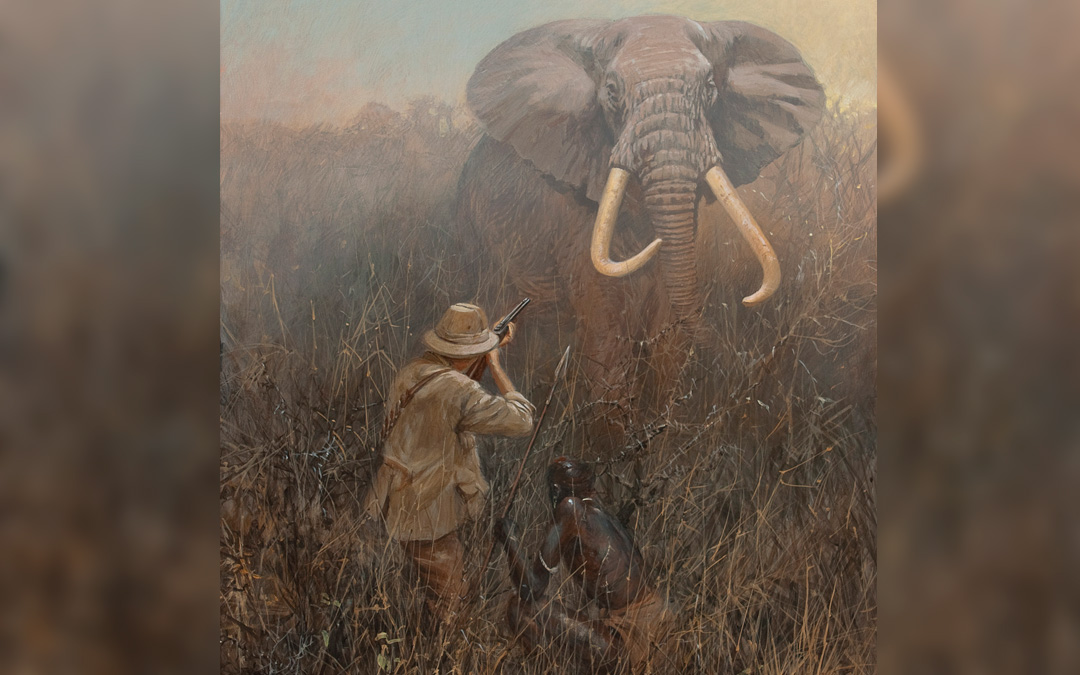

Because of the situation, this was a most difficult scene to compose and recreate. Karamojo Crossing – oil on panel, 18” x 36”

This was the news Bell had been waiting for. He tried to persuade the young man to take him to the area. The native was hesitant and left without giving Bell a decision or a location.

Hours later the native returned, bringing with him a friend, a strikingly tall native, about 35 years old, who had an air of intelligence about him. His name was Pyjale and he would be a blessing to Bell on this safari. The two men would ultimately become long-time friends.

A natural leader, Pyjale soon took control of Bell’s crew. He knew where to find elephants, but warned Bell that the journey was long and that the rains were coming any day. He advised Bell to take tents and be prepared for wet conditions.

Bell was concerned about leaving his main camp and the ivory he’d brought from Mani-Mani. Pyjale assured Bell that everything would be safe at the Bukoras’ manyattas (villages). Once charged with guarding someone’s belongings, the natives would make sure they’d be safe.

Reassured by this, Bell headed out to “no man’s land.” After a hard trek of three days, they reached the Debasien Range where they set up a fly camp. Bell found that all of Pyjale’s predictions had been correct. The rains came in earnest.

The men struggled to set up calico bush tents in the driving rain; even the hardiest of the natives were forced to take shelter. With the rains came other problems. Their camp was swarming with insects and ants of every kind. Scorpions were the worst of the invaders and several members of the safari were stung, including Bell.

To reach the elephants, they had to cross a river that had become a raging torrent of reddish-colored mud. Numerous trees were being swept along and even poisonous snakes. It was impossible to cross, so they decided to stay at camp and wait for the flood to subside.

When the river had finally gone down, Bell rigged a rope across the narrowest stretch to enable his native crew, none of whom could swim, to cross safely. But even with all these precautions, one or two were swept away in the current before being hauled back to safety. On reaching the bank and moving off, they heard elephants in the distance. Although Pyjale doubted they could catch up with the big animals before sundown, they did manage to find the herd with a half-hour of sunlight left.

Bell looked out on a scene he could never have imagined. Before him were hundreds upon hundreds of elephants, so many that the vast marsh had turned black. He moved cautiously, trying not to spook the elephants. But Pyjale rushed forward, urging the white hunter to follow. Fearlessly, he ran beneath angry cows, and with Bell in tow, he raced straight up to the massive bulls, enabling Bell to kill several.

Exhausted yet exhilarated, Bell decided to move back to camp with the ivory and return the next day. He had noticed that even as shots were being fired and the bulls were falling, it did not cause a stampede. He was sure they would be around in the morning.

Next day, however, was a different story. When they returned to the marsh, there wasn’t an elephant to be seen, only their trails leading away in every direction. Pyjale confirmed that during the rains, elephants would go wherever they wish and would be hard to track.

So it was that Bell and his safari headed home with an abundance of “white gold,” crossing a much calmer river in a very different fashion. Weighed down by the heavy tusks across their shoulders, the natives simply held their breaths and walked on the river-bottom. What a remarkable sight that must have been.