“…I could do it if I practiced enough.”

The artist, Julie Jeppsen.

It’s not uncommon, upon meeting Julie Jeppsen for the first time, to find yourself doing a double take just a few minutes later. Let’s say you’re at the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition in Charleston, South Carolina, one of the biggest shows of wildlife/ sporting art in the country. Because her paintings are so riveting, so clearly a cut above the norm, you stop at Jeppsen’s booth to express your admiration. There, you’re delighted to discover that she’s not only radiantly attractive, but warm, engaging and disarmingly ingenuous.

A little while later, you’re surprised to see her in a different part of the exhibition hall. But what’s really puzzling — confounding, even — is that she’s gotten from where she was to where she is and changed her clothes head-to-toe. How’d she do that?

Royal Flush, which depicts a timber wolf pursuing a flock of ptarmigan. Oil canvas.

Well, the answer to the riddle is that Jeppsen didn’t do anything. Instead, it’s what her mother did that leaves people blinking and scratching their heads. Thirty-six years ago, you see, she gave birth to identical twin girls.

“We cause a lot of confusion,” laughs Jeppsen, “we” meaning she and her sister, Janet Smith, who often lends a helping hand at major art shows. Quite frankly, they also turn a lot of heads.

Grizzly Country, oil canvas.

But what there is no confusion whatsoever about is that Julie Jeppsen is one of the freshest, most exciting young painters to come down the pike in recent memory. There’s much to praise in her work: the clean, sure rendering; the rich color; the strong, simple design; the sense of authenticity; the creation and conveyance of a palpable mood. But it is Jeppsen’s masterful — almost a palpable mood. But it is Jeppsen’s masterful — almost magical — handling of light that truly sets her apart. It infuses her art with aluminous quality that invites comparison to the greats — the Rungiuses, the Kuhns, the Carlsons. Predictably, these are the artists Jeppsen calls her “idols.” In their painterly, “gutsy” approach she finds both challenge and inspiration.

Julie Jeppsen’s art is the product of native talent, hard work — and virtually no formal training. “It was something I always did,” she recalls. “When I was in the second grade, I drew all the pictures for the school’s spring festival. I sold my first painting when I was 14, and in high school I paid my rodeo entry fees by selling drawings to my friends — until my mom made me quit because she thought I was spending too much time drawing and not enough time studying.”

Sweethearts, a 12×16 oil painted in 1995 (detail).

Indeed, you could say that art and rodeo were Jeppsen’s “twin” passions as a teenager. Growing upon the family ranch in Spanish Fork, Utah, she was steeped in the culture and traditions of the American West. It was natural that she gravitate to rodeo; both Jeppsen and her twin sister competed in five different events, including breakaway calf roping, barrel racing and goat tying. Early on, she learned an important lesson that would eventually help her hit the ground running when she decided to become a full-time artist: there’s no substitute for practice.

“When I was a freshman,” Jeppsen relates, “I didn’t make it to the state finals rodeo. Several of my friends did, though, and in my heart I knew I was as good a rider as they were. So instead of practicing one day a week, I started practicing every — every day. As a sophomore, I not only made it to the state finals in goat tying, I finished 10th in the nation. Then in my junior year I moved up to ninth in the country and my sister was fourth.”

Ultimately (and somewhat ironically), the work ethic instilled by Jeppsen’s rodeo experience would prove far more valuable to the development of her art than anything she learned in the classroom. “I didn’t even take art,” she shrugs. “I was already doing paintings of cowboys on bucking broncos, so there wasn’t much they could teach me.”

After attending college for two years and earning an associate degree in business, Jeppsen set about the business of raising a family. And, characteristically, she went at it full speed ahead. Jeppsen had her first child in1981; she had her fifth (and last) just seven years later exactly the way she planned it.

Rush Hour reflects Jeppsen’s love for “lots of color and big brushes to get a strong structure that makes my animals not just look painted, but alive and eye-catching,” she says.

“I wanted to have my children,” she explains, “before I seriously pursued my art career. I knew that it would be educational for them — and fun. It gives us an excuse to do neat things together, like go camping in the Salmon River Wilderness of Idaho so I can get reference for bighorn sheep paintings.”

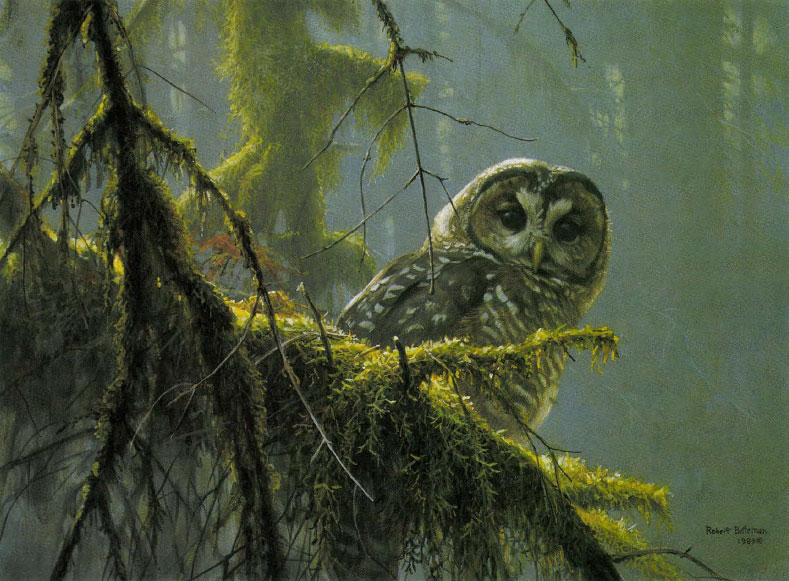

Even while she was knee-deep in toddlers, Jeppsen continued to paint, stealing away to her easel in the wee hours of the morning when the rest of the family was asleep. It was her way of relaxing, a kind of gift she gave herself. She began selling a few paintings (“Or trading them for furniture,” she laughs), and exhibiting her work at county fairs and local art shows. She also began attending wildlife art workshops in an effort to improve her craft. A class led by renowned Canadian artist Robert Bateman did just that, but it was John Seerey-Lester who, during a 1990 seminar, gave Jeppsen the confidence she needed to take the next step.

“We were expected to bring a completed painting for him to critique,” she recalls. “I’d done a painting of a bear, and when he came to it he looked up and said, ‘Who did this?’ I raised my hand and said, ‘I did.’ He was really impressed with it, and told me then and there that I should be showing nationally.”

In Moonlight Hunt she used soft blues and tinges of purple to create the illusion of nighttime.

Jeppsen heeded Seerey-Lester’s advice and exhibited several paintings at the 1991 Pacific Rim show in Seattle. Talk about auspicious debuts: In her first appearance on the national stage, Jeppsen won the show’s prestigious Auction Award. Shortly thereafter, she became the talk of the Charles Russell show in Great Falls, Montana, when she brought her own raised-from-a-pup wolf, Arctic, and painted him from life in the popular “Quick Draw.” (For those who are unfamiliar with it, a quick draw is an event in which artists are given thirty minutes to complete a painting — in front of an audience.) Jeppsen’s dramatic portrait of Arctic not only wowed the standing-room-only crowd of 1,200, it rated the front page of the local paper.

Truth to tell, though, the painting wasn’t quite as extemporaneous as it appeared. Borrowing a page from her rodeo era, Jeppsen painted Arctic five times a day, every day, for three weeks prior to the show. By the time the clock started ticking at the quick draw, she could have painted that wolf in her sleep.

“The first time I tried to paint him,” she admits, “it took me two hours — and it looked terrible. But I knew I could do it if I practiced enough.”

Practice doesn’t necessarily make perfect, but it can get you mighty close — especially if, like Julie Jeppsen, you’re blessed with a truckload of talent to begin with.

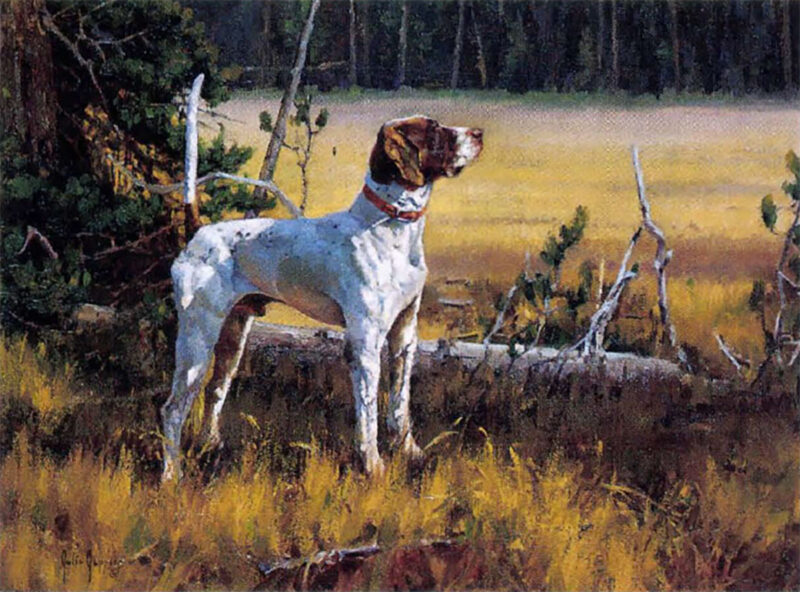

Elhew Snakefoot, Top Shooting Dog of the Year in 1994-1995

These days, while Jeppsen continues to focus primarily on wildlife and western paintings (Trailside Americana Galleries is her representative), she’s added some new subject matter to her portfolio: bird dogs. One of her fellow exhibitors at the 1995 Southeastern Wildlife Expo was none other than Robert G. Wehle, sculptor of sporting bronzes and proprietor of the famed Elhew Kennels (see “The Making of a Legend,” May/June ’96). A long-time collector and keen student of art, Wehle instantly divined something special in Jeppsen’s work. He bought two paintings on the spot, then casually inquired if she’d ever tried her hand at depicting dogs. Jeppsen replied that she hadn’t, but stressed — a tad boastfully, perhaps — that, given the right price, she could paint any animal.

Apparently, the price was right. Jeppsen’s stirring portrait of National Champion Elhew Snakefoot graces the jacket cover (and frontispiece) of Wehle’s book, Snakefoot: The Making of a Champion. Several other Jeppsen canvases are reproduced as well, along with numerous line drawings commissioned specifically for the book. She clearly has a discerning eye when it comes to anatomy and musculature, but more than that, she has the rare ability to capture the character of the individual dog, its fire and pride and soul. Plus, she possesses the discipline and restraint not to impose preconceived ideas on her subjects. As Wehle puts it, “She doesn’t take liberties.” She gets it right, and while she does it with style, she doesn’t stylize.

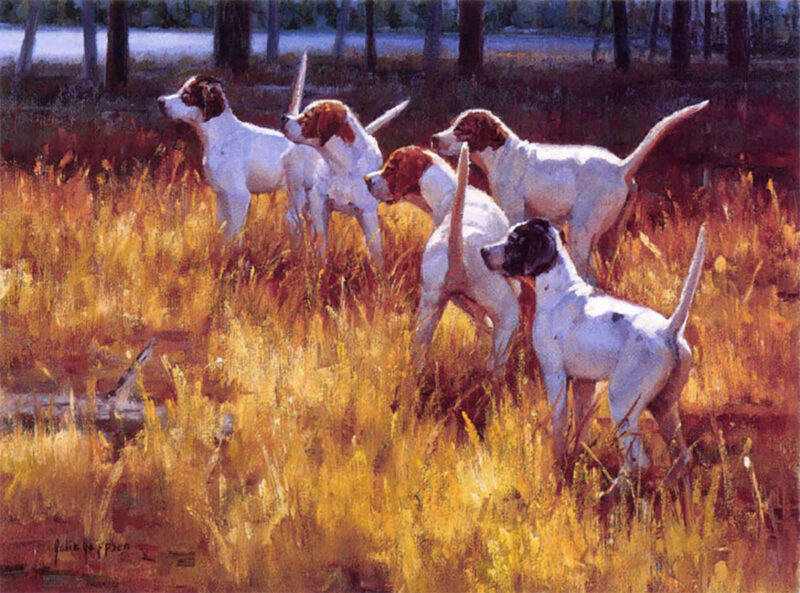

Several Elhew Snakefoot puppies.

While the Wehle connection has enabled Jeppsen to explore new artistic terrain and stake her claim as a painter of dogs, it’s led to other, unforeseen places as well. Her recent marriage, for example. (Her first marriage ended in divorce.) It’s a long story, but it boils down to a chance encounter in a one-horse town on the Texas Panhandle, where professional trainer Jack Herriage was working his string of field trial dogs. Jeppsen was there to gather reference for a painting commissioned by a friend of Wehle’s; Terry Moore, a field trial enthusiastic from southern Illinois, was there to check on the progress of a couple of pointers he had in training. It had to be fate: Jeppsen was originally scheduled to return to Utah before Moore arrived, but bad weather forced her to stay on in order to get the photographs she needed. The two of them hit it off famously. Following a long-distance courtship, they wed last July, ten months after they first met.

It was the culmination of a whirlwind summer for Jeppsen: Literally a few days before tying the knot, hers had been one of a dozen covered wagons to complete a four-week, 465-mile ride across Utah as part of the state’s centennial celebration. (The event began with a train of over one hundred wagons.) All five of her children accompanied her, as did her sister, with whom she’d bought the splendidly matched pair of Halflinger mares (a small, rare, strikingly beautiful draft horse) that pulled their prairie schooner. They dressed in period garb, endured heat and dust and long days on the trail, but Jeppsen gathered “fantastic” material for her paintings and made memories that none of them will ever forget.

And yes, Jeppsen and her sister continued to cause their fair share of confusion. “It took about three days,” she notes, “for the rest of the wagon train to figure out there were two of us.”

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now