If a tail flies high or a docked tail raises, the enjoyment of watching these dogs work in terrain that seems impenetrable is inspirational.

Places in snow country are reported to have lots of words to describe the white, powdery flakes gracing their winter countryside. Maybe that’s true, but at home in New England we have the same with stone walls. Scratch farmers in our country’s earliest years had to clear rocks struck by the point of a moldboard plow. They’d hump the granite, soapstone, flint and quartz to the field edges and toss ’em in a neighborly fashion. These low-to-the-ground structures were called dumped walls and they served no purpose other than to allow for more successful tilling.

As animals were added to the family farm the rocks were stacked to create natural fences, ideal for herds of sheep and goats. These tossed walls were single rows, and when horses and cattle arrived on the scene a second row was added for strength, durability and height. The pinnacle of stone barriers are laid walls, for the geometrically-arranged stones were fit together as a mosaic. They revealed a landowner’s wealth, which usually was significant.

When I find these walls during bird season I listen to them speak. They tell me about the hardworking farmer and his family who struggled until one day they gave up. Maybe they took a job in a city or maybe they pursued opportunities out West. But all was not lost, for with their abandonment came regeneration of a different kind, and young forests and shrubs emerged in the clearings they left behind. Grouse and woodcock, descendants of the original Pilgrim-era stock, flourished. To this day we bird doggers see any variety of stone walls and park our rigs in an inconspicuous area and put down a dog for a run.

For this type of terrain, a cover dog works best. Breed isn’t as important; athletic, close-working setters, pointers, Brittanys and shorthairs are fine. They’ve got to know how to carve up the jungle, have a head packed with bird smarts and a nose to differentiate foot from body scent. A cracking tail indicates their joy in accepting such a difficult challenge.

These specialists work at a pace that allows for hunters snaking their way through a young alder or aspen run to keep up. Good dogs have the wheels to move out in front, to cast from side to side and to check in with handlers before advancing onward. That cover dogs run inside of bell range doesn’t make ’em bootlickers. Some cast closer than others, but their prey drive is such that they’ll scour the countryside in search of birds. Hunters can find a lineage to suit personal preference.

Bird finders of the highest order differentiate between grouse and woodcock that inhabit alder, poplar and aspen runs, stands of spruce or fir trees, and the smorgasbord of soft and hard mast and leafy greens. They know to check under a pine bough on a wet day as much as they head to the alder hells when it’s bone dry. After a killing frost they’ll look for grouse feeding among fallen apple trees and drooping highbush cranberry branches, and if nobody is home they’ll look for birds feasting either on ferns or grazing in witchhazel and wintergreen. Dogs capable of such performances are athletic indeed, and they twist and turn like an Olympic platform diver.

To keep up, hunters should be conditioned. For those of us who have neglected summer two-a-days, well, we can always visit a chiropractor.

Cover dog aficionados are split when it comes to a coat and coloration. Setter or Brit fans favor long hair as it keeps Hawthorne tines and bull briars at bay, while a pointer or shorthair’s high-and-tight is ideal for early season heat. White dogs are easier to spot in thick foliage, while dark dogs stand out when the snow falls. Take your pick and hunt what you like so long as they are biddable and check in from time to time.

Our birds behave differently, so a cover dog must hunt accordingly. Grouse and resident woodcock are notorious track stars, so dogs will relocate several times after an initial bird contact. Running grouse have all the stutter-steps of an All American halfback, while running timberdoodles are as graceful as a lineman doing an end-zone dance. Juxtapose them with stationary flight woodcock and you’ll need a dog with enough savvy to present a hunter with Check Mate.

Cover dogs are at home in cover, but they’re popular in other areas, too. Shawn Wayment favors cover dogs for a variety of Western birds, and Tracy Lieske, Jack L. Bailey and Ty Wilson like ’em for foot-hunting Tennessee bobs. Regardless, if a tail flies high or a docked tail raises, the enjoyment of watching these dogs work in terrain that seems impenetrable is inspirational.

Cover dogs have stories to tell. Just like an ancient New England stone wall.

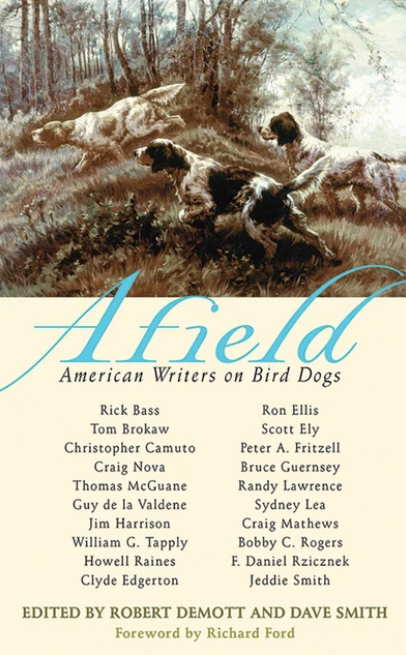

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo and Chris Camuto come together in one collection.

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo and Chris Camuto come together in one collection.

Hunters and non-hunters alike will recognize in these poignant tales the universal aspects of owning dogs: companionship, triumph, joy, forgiveness, and loss. The hunter’s outdoor spirit meets the writer’s passion for detail in these honest, fresh pieces of storytelling. Here are the days spent on the trail, shotgun in hand with Fido on point—the thrills and memories that fill the hearts of bird hunters. Here is the perfect gift for dog lovers, hunters and bibliophiles of every makeup. Buy Now