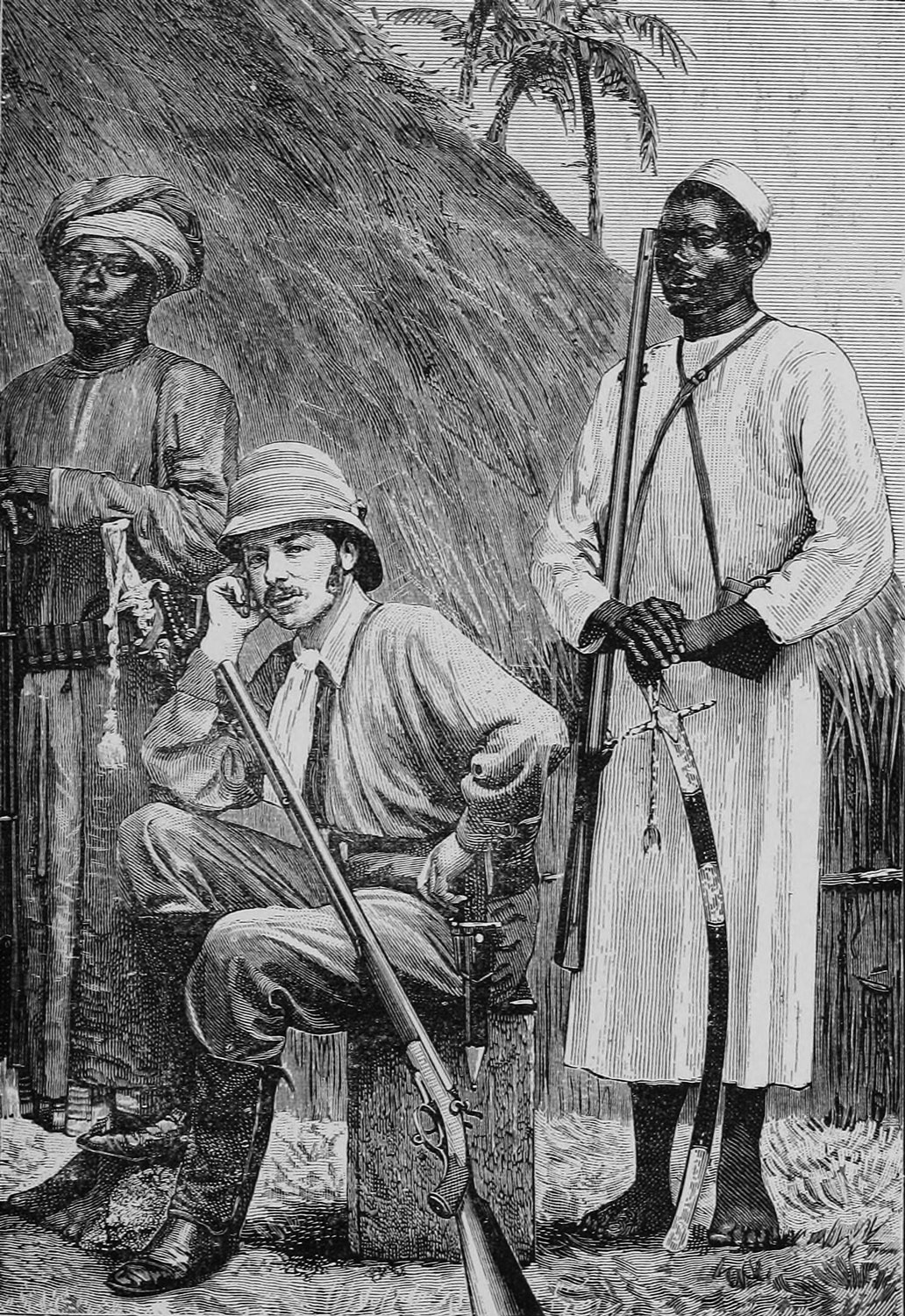

Over the course of the 19th century, phenomenon sometimes referred to as “the opening up of Africa,” hunters and explorers, along with a solid sprinkling of traders, were in the forefront. They pioneered the way into the interior and their tales of grand adventures, many of which became bestsellers, stirred the European imagination in a fashion directly linked to a complicated clash between various countries for hegemony in the “Dark Continent.” With England, France and Germany leading the way, and Portugal long having been an established imperial presence in Africa—not to mention the ambitious scheming of King Leopold of Belgium seeing that small country become involved in an outsized way—you had an unseemly, often bitter competition for control over almost all of sub-Saharan Africa. That would, as it festered over several decades, become one of the critical factors underlying World War I.

In the background to these momentous international developments were the exploits of a goodly number of exceptional individuals, men (and a scant handful of women) who collectively were the underpinning of the late 19th and early 20th century white presence in the heart of Africa. These brave individuals, and in many cases foolhardy might be a better description than brave, went in search of many things. Among them were enjoying incomparable hunting over vast tracks of terrain holding strange and sometimes dangerous beasts in almost incomprehensible numbers, seeking fortunes through acquisition of ivory, answering a siren’s call to adventure, dedication to spreading Christianity, ending the insidious slave trade, searching the fame sure to result from solving ages old geographical mysteries such as the whereabouts of King Solomon’s mines or the source of the Nile River and quite often simply to find themselves. Almost without exception these pioneers taking the first footsteps into the vast African interior were strikingly unusual personalities.

They were cut from the mold of men noted poet Robert Service describes in “The Men That Don’t Fit In.”

There’s a race of men that don’t fit in,

A race that can’t stand still;

So they break the hearts of kith and kin,

And they roam the world at will.

They range the field and they rove the flood,

And they climb the mountain’s crest;

Theirs is the curse of the gypsy blood,

And they don’t know how to rest.

These hunters and explorers were a distinctive lot in background, personality and motivation, but an exceptional number of those in their ranks were Scottish by birth, family background or both. Rootlessness, restlessness and a decided propensity to wander far afield have long been recognized almost as national traits for individuals linked to the northernmost portion of Britain. As early as the middle of the 1600s, poet John Cleveland recognized this fact in oft-quoted lines comparing natives of the region to the Biblical son of Adam and Eve destined to wander forever as punishment for killing his brother: “Had Cain been Scot, God would have changed his doom, nor forced him wander, but confine him home.”

Scots who figure prominently in unveiling the geographical and sporting wonders of Africa read like something of a “Who’s Who” in those fields of endeavor. There was Roualyen Gordon-Cumming, a wealthy Highlands daredevil who cared naught for fame and possessed the inherited fortune to hunt in uncharted lands to his heart’s content. Dr. David Livingstone, perhaps the most recognizable of all 19th century adventurers in Africa, was in many ways a polar opposite to Gordon-Cumming. Impoverished, keenly interested in fame and far more devoted to discovery of terra incognita than to the saving of African souls in his guise as a missionary (in all his years in Africa he converted precisely one native, and that petty chieftain soon proved to be a backslider), Livingstone somehow managed to capture the Victorian imagination despite his many shortcomings. Then there was James Augustus Grant, the staunch companion of John Speke, discoverer of Lake Victoria, and Victorian authority on all things African. Numerous other notable names in the continent’s unveiling—among them Verney Lovett Cameron, Sir Richard F. Burton and Sir Harry H. Johnston—had forebears from Scotland. Add individuals such as James Bruce, explorer of the Blue Nile; Mungo Park, who sought fame on the Niger River; and Hugh Clapperton, the first European to give reports of Nigeria, and the picture is quite clear—Scots were drawn to Africa in inexorable fashion.

Yet in many ways the Scot who was the most interesting of all ranks among the least known. Sir Harry Johnston once reckoned that it seemed “an explorer laying bare to our knowledge hundreds of thousands of square miles of territory was less worth of remembrance than a charge d’affaires at the court of the Grand Duke of Pumpernickel.” His complaint (Johnston himself was an explorer of note, the man who observed and identified the elusive okapi, and possibly the first European to reach the permanent snow line on Mount Kilimanjaro) might have been writing with Joseph Thomson specifically in mind.

The fifth son of a journeyman stonemason turned tenant farmer, young Joseph developed strong interests in natural history, geology and other sciences while still a small boy. Legend has it that when he was scarcely in his teens, he wanted to go to Africa to find and rescue long missing fellow countryman David Livingstone. Exceptionally gifted intellectually, Thomson managed to gain entrance to the University of Edinburgh and studied under the tutelage of Archibald Geikie along with taking courses in natural history taught by famed Victorian scientist Thomas H. Huxley. Certainly he had developed a compelling interest in Africa well prior to his 1878 graduation. In time he would become so enamored of the continent that he once told a friend he would die “with the spirit of Africa at my lips.” The toll adventures on the continent took on him pretty well fulfilled that self-prophecy. For the moment though, he considered it both an omen and a stroke of good fortune that his response to a small newspaper advertisement led to him being appointed naturalist and geologist to an expedition headed by A. K. Johnston and sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) that was scheduled to depart Britain, not long after his graduation, to explore the little known interior of East Central Africa.

The fifth son of a journeyman stonemason turned tenant farmer, young Joseph developed strong interests in natural history, geology and other sciences while still a small boy. Legend has it that when he was scarcely in his teens, he wanted to go to Africa to find and rescue long missing fellow countryman David Livingstone. Exceptionally gifted intellectually, Thomson managed to gain entrance to the University of Edinburgh and studied under the tutelage of Archibald Geikie along with taking courses in natural history taught by famed Victorian scientist Thomas H. Huxley. Certainly he had developed a compelling interest in Africa well prior to his 1878 graduation. In time he would become so enamored of the continent that he once told a friend he would die “with the spirit of Africa at my lips.” The toll adventures on the continent took on him pretty well fulfilled that self-prophecy. For the moment though, he considered it both an omen and a stroke of good fortune that his response to a small newspaper advertisement led to him being appointed naturalist and geologist to an expedition headed by A. K. Johnston and sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) that was scheduled to depart Britain, not long after his graduation, to explore the little known interior of East Central Africa.

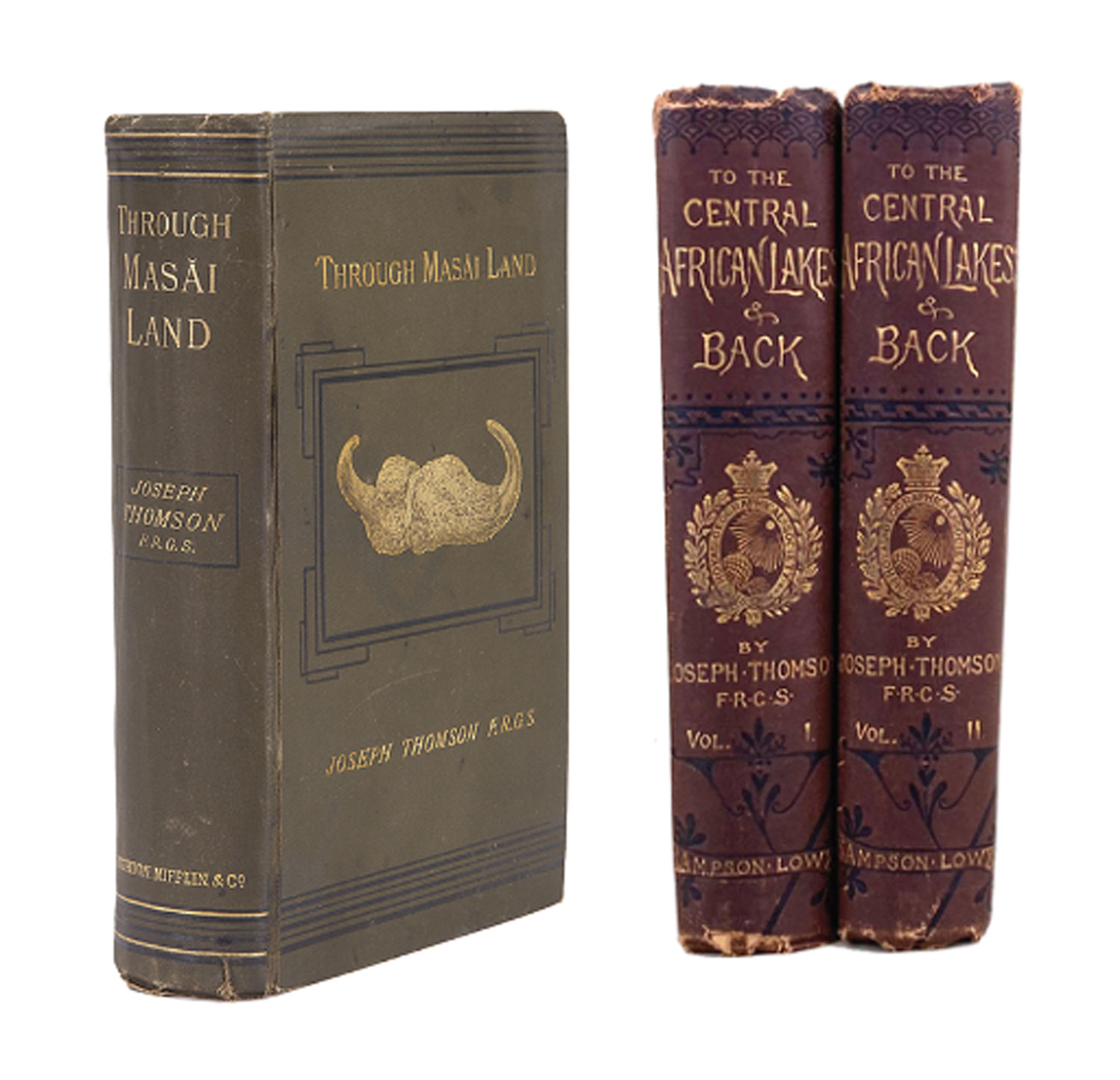

The undertaking’s leader, Johnston, died less than six months into the journey and Thomson unexpectedly found himself in the position of expedition leader. He performed admirably and accomplished a great deal for an untested man still in his early 20s. That included confirming a number of details about the outlet of Lake Tanganyika and becoming the first white man to lay eyes on Lake Leopold. Thomson eventually made his way safely to the East African coast and then the island of Zanzibar, dealing along the way with mutinous caravan bearers and recalcitrant native tribes, and thence sailed for England. Back in the British Isles, and still short of his 24th birthday, he wrote and saw published a massive two-volume travelogue, To the African Lakes and Back (1881), that brought him acclaim from the reading public and accolades from the geographical establishment.

“He who goes gently, goes safely; he who goes safely, goes far.”

Thomson’s mantra enabled him to befriend wary and guarded Maasai warriors, who subsequently took his safety as their responsibility and guided him through challenging and dangerous terrain.

A variety of other African experiences would follow over the course of the 1880s. He first, unsuccessfully, sought deposits of coal on the mainland for the Sultan of Zanzibar and then, in 1882, under the sponsorship of the RGS, undertook an attempt to open up a direct route from the East African coast to Lake Victoria. The planned route called for travel through the lands of the dreaded Maasai tribe, widely feared for their warlike ways and willingness to attack any and all European travelers. From the outset, Thomson determined to take an approach strikingly different from that employed by other hunters and explorers of the era. Many of scarcely gave second thought to employing firearms and shooting their way through any troubles that might arise, figured that superior technology in the form of firearms gave them a self-assumed right to force their way through Africa. Instead of that sometimes-deadly approach, from the outset and throughout his career, Thomson adopted a peaceful, easygoing motto: “He who goes gently, goes safely; he who goes safely, goes far.” For him, it worked.

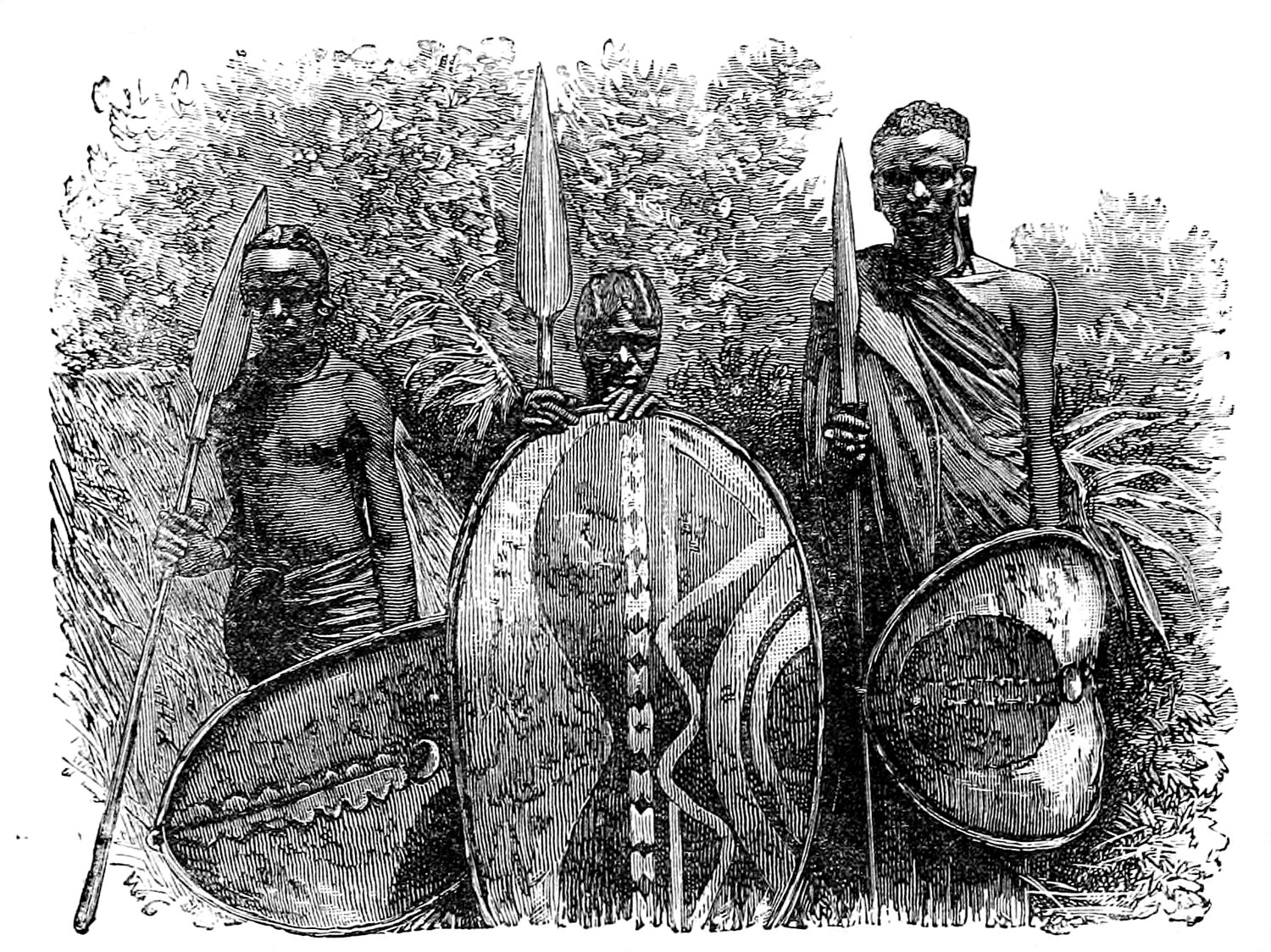

That approach, along with a winning personality and genuine “feel” for bits of seeming legerdemain that awed even the belligerent but superstitious Africans, served him well with the Maasai. Exceedingly tall and possessed of seemingly inexhaustible energy, the Maasai were an impressive, fearsome sight. Adult males, with braided hair dyed with red ochre, carried long spears while going about their means of existence—raising and herding cattle. The deadly spears, with blades almost two feet long and two inches wide, could be thrown with sufficient force to pass through the entire body of an enemy. Even the Maasai diet, consisting primarily of milk curdled with blood taken from the veins of living cattle (the pierced vein would be packed with mud after a quantity of blood had been drained), was intimidating.

Thomson succeeded in dealing with them where all predecessors had failed and sometimes died at the hands of the Maasai. He did so thanks to a ready smile, the ability to suck back a partial plate in his mouth and seemingly become toothless in an instant, and through the use of effervescent Eno Salts, a powdered antacid that enabled him to foam purple at the mouth as soon as the common nostrum made contact with his saliva. These and other bits of magic led the Maasai to believe he had special powers or was imbued with a mystical aura. So strong was his impact that even today he is remembered in the region as a European to be admired, even revered, when others from the age of imperialism are reviled.

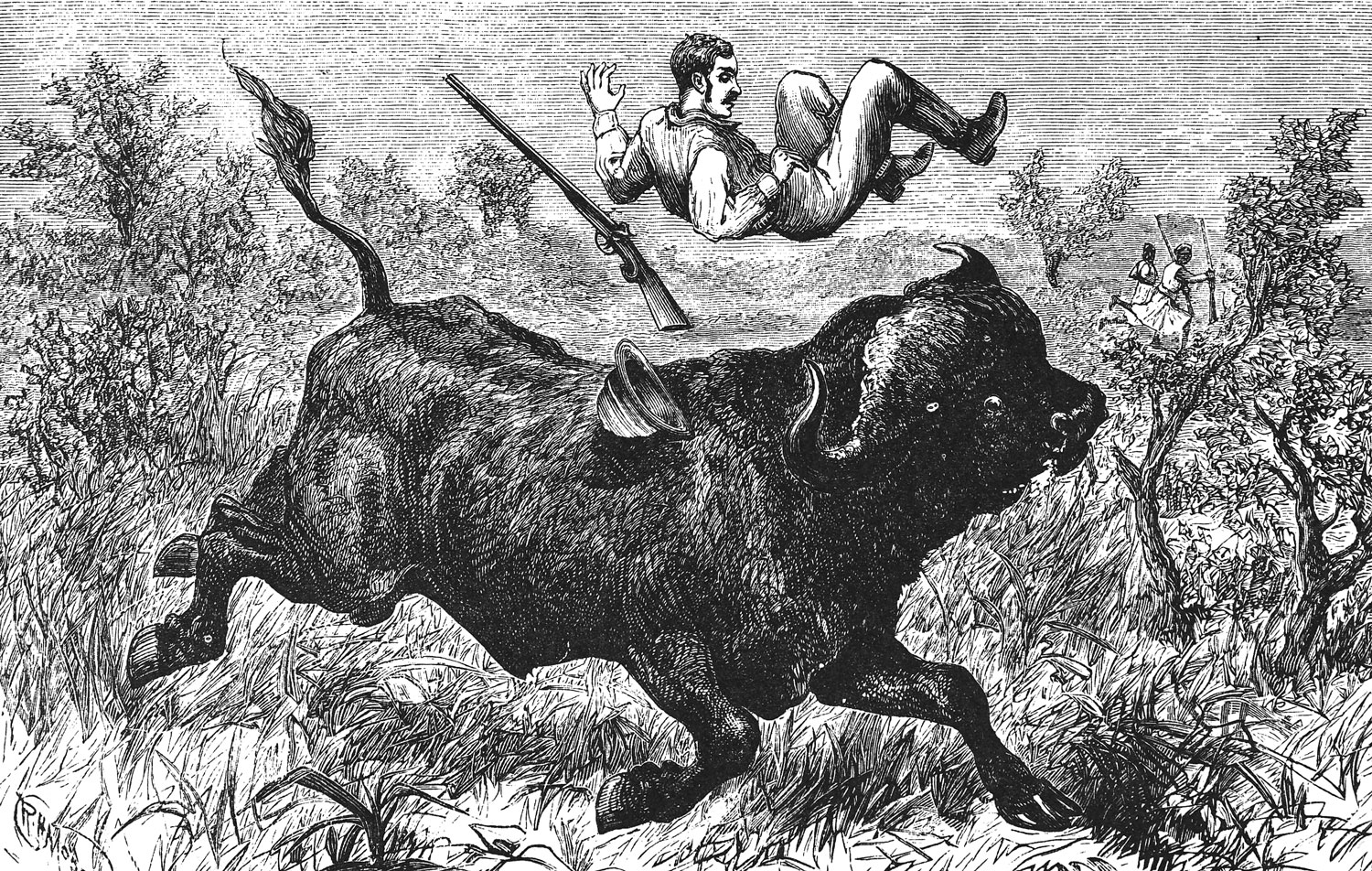

Not all of Thomson’s experiences on this epic journey, which not only saw him traverse Maasailand but also visit Mount Kenya, Lake Navaisha and Lake Baringo, Mount Elgon, and discover the Aberdare mountain range, were quite as placid. On the final day of 1882, six weeks shy of his 25th birthday, he had an encounter with a buffalo he wounded during the course of a hunt. The animal, which most hunters of that era as well as today considered Africa’s deadliest, nearly killed him. Badly gored, he had to be carried in a litter for weeks and then, just as he had begun to recover, onset of a devastating case of dysentery plagued him. After two months of being so weak his caravan could not move, he finally made his way back through Maasailand and in late June of 1883 managed a few feeble footsteps on his own—the first he had taken for months.

Eventually he made his way back to the coast, on to Zanzibar and thence to London, where he became the toast of Britain. His massive account of his adventure, Through Masai Land (1884), was a sensation. He gave a number of public lectures, wrote scholarly papers on his adventures and discoveries, received the coveted Gold Medal of the RGS and, for a short time, reveled in renown. Yet such recognition meant little to him, and by the time of the ceremony in which the RGS formally bestowed its most prestigious medal, Thomson was already back in Africa. This time he was working for the National African Company in the western Sudan. There he managed to procure a number of treaties from Sudanese leaders that protected British interests in the region.

He returned home from this endeavor a weakened, sickly man, and for a portion of 1885 and all of 1886 and 1887, he rested and attempted to restore his fragile health. Then followed a series of further African endeavors that would highlight the remainder of his quite short life. These included explorations in the Atlas Mountains of North Africa where he climbed a number of peaks topping out above 12,000 feet; a brief stint of service with the Imperial British East Africa Company; and then, in 1890, employment with the British South African Company headed by Cecil Rhodes. In the course of the latter endeavor, which was primarily diplomatic in nature and involved little sport other than shooting for the camp pot, Thomson was attacked with cystitis. His health suffered irreparable damage and he never fully recovered from the cumulative impact of the various maladies associated with his African endeavors as a natural historian, hunter, explorer and agent of imperialism.

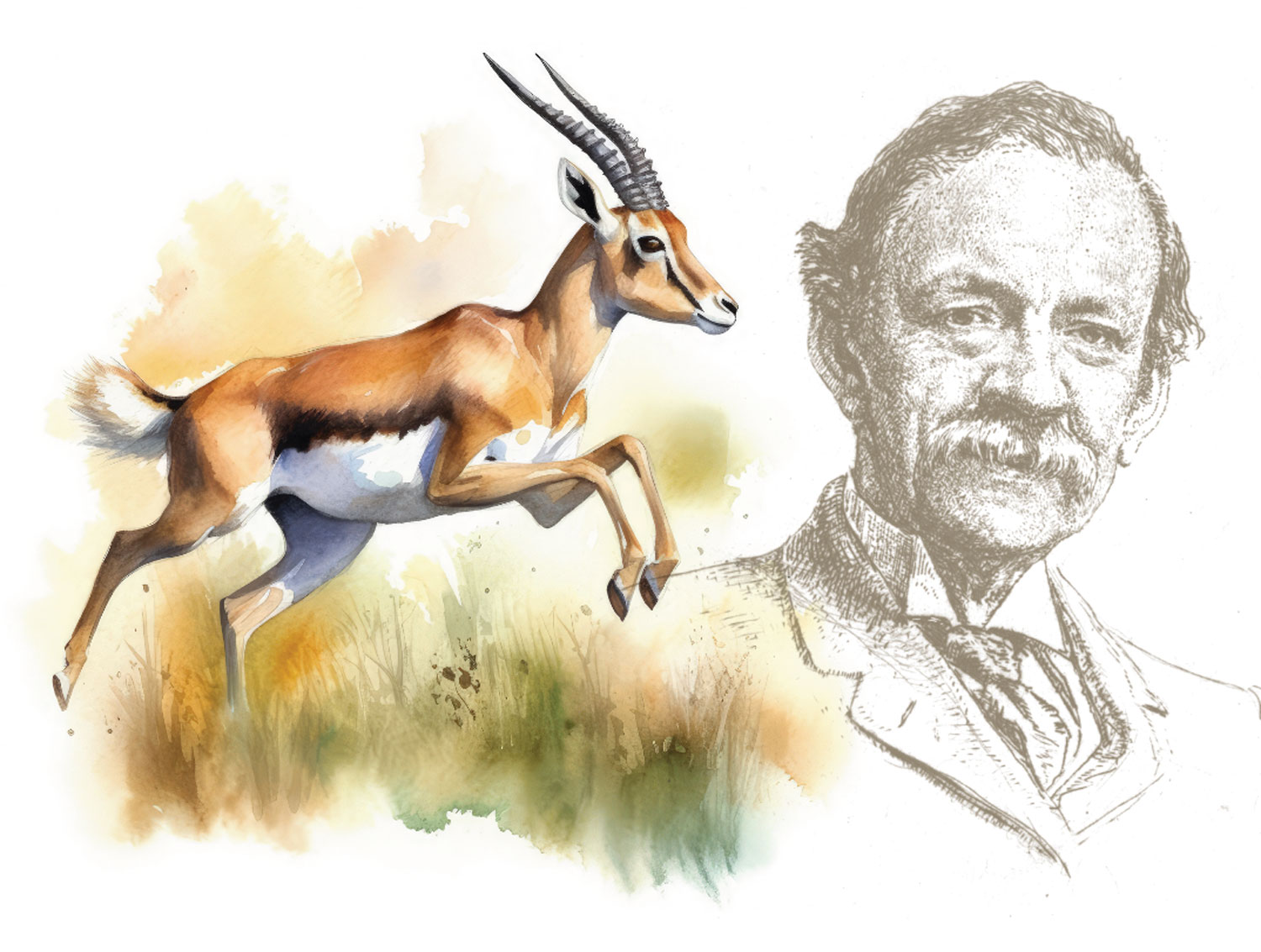

Most modern international hunters readily recognize the name of Thomson’s gazelle, but rarely do they know anything about the fascinating man for whom the animal is named.

Even so, dauntless to the end, mere months before his death in early August 1895 aged 37, he was planning an expedition to Mashonaland in the South African interior. Discerning students of the great age of African exploration sometimes advance his name as the quintessential traveler in the Dark Continent, and without question there is much to applaud about his ability to deal with natives. He made multiple contributions, major and minor, to natural history and various scientific and common names for flora and fauna bear his name. The best-known of these is Thomson’s gazelle, one of East Africa’s most plentiful game animals. The beautiful “tommie” with its striking horns is one of the world’s fastest animals. Today the only place they can be hunted in their native habitat is in the Maasailand portion of Tanzania, although the species has been successfully established in Texas.

Most modern international hunters readily recognize the name of Thomson’s gazelle, but rarely do they know anything about the fascinating man for whom the animal is named. Yet in many ways Thomson’s short career was as compelling as the gazelle is lovely, and to take a peek into the life of this Victorian Africanist is to be transported back to a world of sporting wonder we have long since lost.

Books By and About Joseph Thomson

Somehow, amidst his repeated forays into Africa, Thomson found time to be a quite prolific writer, especially when one considers how short his life was. His book-length works, in order of publication, include To the Central African Lakes and Back (1881—2 volumes), Through Masai Land (1883—this book was edited and abridged by Roland Young and reissued in 1962), Ulu: An African Romance (1888—a fictional work coauthored with E. Harris Smith), Travels in the Atlas and Southern Morocco (1889) and Mungo Park and the Niger (1890). He also wrote numerous articles for scientific and popular magazines. H. Rider Haggard used some of his concepts of travel among the Maasai in his novel She. One of Thomson’s brothers, Reverend J. B. Thomson, wrote a standard Victorian “Life and Letters” biography, Joseph Thomson: African Explorer (1896). The standard biography of Thomson is Robert I. Rotberg’s Joseph Thomson and the Exploration of Africa (1971). There is considerable material on his Maasai travels in Charles Miller’s The Lunatic Express (1971).

This article originally appeared in the 2024 July/August issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

Learn more about the era of pioneering adventurers in Jim Casada’s book Lords of the Veldt & Vlei. This account looks at some of the mightiest and most mesmerizing of these Nimrods, chronicling their careers while highlighting their eccentricities, delving into the factors that drove them, and sharing their achievements. Each profile is accompanied by a selection from published accounts by these pioneers of African sport, and dozens of vintage photographs and captivating pieces of art that offer a striking visual accompaniment to this saga of splendid sport.