José Ortega y Gasset lived from 1883 until 1955 and enjoyed success as an essayist and a scholar throughout his career. He wrote extensively about concerns of truth as it pertains to reason and circumstance and became a key figure in the emerging existential movement.

While Ortega y Gasset is noted for his influence on philosophy and politics, in 1972 Charles Scribner’s Sons published an English translation of his essays on pursuing game entitled Meditations on Hunting. Since the book’s initial release, it has become a staple among thinking sportsmen and stands as one of the finest works of rhetoric about the relationship of man and prey.

We’ve excerpted below nine passages from the book that we find particularly insightful. —JR Sullivan

In our rather stupid time, hunting is belittled and misunderstood, many refusing to see it for the vital vacation from the human condition that it is, or to acknowledge that the hunter does not hunt in order to kill; on the contrary, he kills in order to have hunted.

The hunter who accepts the sporting code of ethics keeps his commandments in the greatest solitude, with no witness or audience other than the sharp peaks of the mountain, the roaming cloud, the stern oak, the trembling juniper, and the passing animal.

Life is a terrible conflict, a grandiose and atrocious confluence. Hunting submerges man deliberately in that formidable mystery and therefore contains something of religious rite and emotion in which homage is paid to what is divine, transcendent, and in the laws of Nature.

“Natural” man is always there, under the changeable historical man. We call him and he comes—a little sleepy, benumbed, without his lost form of instinctive hunter, but, after all, still alive. Natural man is first prehistoric man—the hunter.

The hunter is the alert man. But this itself—life as complete alertness—is the attitude in which the animal exists in the jungle.

A fascinating mystery of nature is manifested in the universal fact of hunting: the inexorable hierarchy among living beings. Every animal is in a relationship of superiority or inferiority with regard to every other. Strict equality is exceedingly improbable and anomalous.

When you are fed up with the troublesome present, take your gun, whistle for your dog, and go out to the mountain.

Man is a fugitive from nature.

We have not reached ethical perfection in hunting. One never achieves perfection in anything, and perhaps it exists precisely so that one can never achieve it. Its purpose is to orient our conduct and to allow us to measure the progress accomplished. In this sense, the advancement achieved in the ethics of hunting is undeniable.

Cover photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

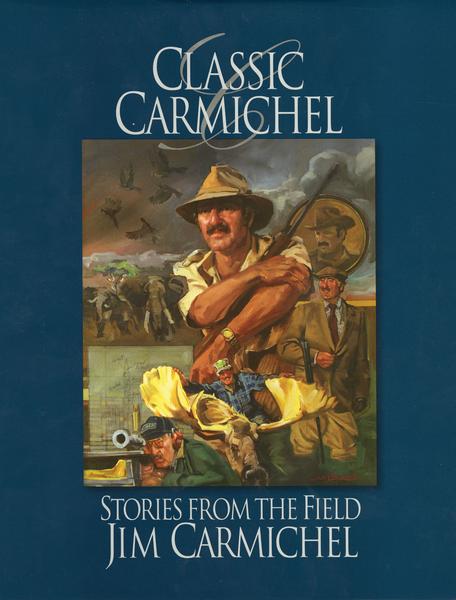

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form —until now.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form —until now.

Classic Carmichel features nearly 400 pages of hunting adventures and firearms expertise by Carmichel, widely acknowledged as one of the foremost experts on sporting arms.

Carmichel’s exploits and prowess had no equal during what is arguably the Golden Age of international hunting and shooting. These are not just stories by a well-traveled adventurer—they are pure literature, written with a style and eloquence that deserve inclusion in any collection of great outdoor books and writers. The big 9 x 10½-inch book will feature more than a hundred never-before-published photographs. Buy Now