“If Jack London had been a painter instead of a writer,” they say, “he would have wielded a brush like Jon Van Zyle.”

The world knows Alaska as a mosaic of idylls: “Land of the Midnight Sun” is one. “Keeper of the Northern Lights” and “America’s Last Frontier” are others. But in the deepest throes of Arctic wilderness, where mushers and yellow-eyed sled dogs share the unforgiving tundra with wolves and caribou, people invoke the names of two men who have brought the slogans to life. “If Jack London had been a painter instead of a writer,” they say, “he would have wielded a brush like Jon Van Zyle.”

The world knows Alaska as a mosaic of idylls: “Land of the Midnight Sun” is one. “Keeper of the Northern Lights” and “America’s Last Frontier” are others. But in the deepest throes of Arctic wilderness, where mushers and yellow-eyed sled dogs share the unforgiving tundra with wolves and caribou, people invoke the names of two men who have brought the slogans to life. “If Jack London had been a painter instead of a writer,” they say, “he would have wielded a brush like Jon Van Zyle.”

While Van Zyle’s signature is synonymous with the Alaskan scene, his reputation as an outdoor adventure artist transcends the boundaries of the 49th State. His paintings are held in museum collections throughout North America and acquired by sportsmen for the same reason London’s Call of the Wild is revered as a classic. They tell the story of authentic Alaska, a larger-than-life landscape of 586,000 square miles, steeped in legend and romance. Interpreting them is Van Zyle’s forte.

“Alaskan art reflects a different world and attitude, which is why it attracts international attention,” says Steven Broocks, assistant to the director of Frye Art Museum in Seattle, which will host an exhibition of 50 Van Zyle paintings and etchings this May. The museum is known for its collection of Alaska genre art, and curators say Van Zyle’s compositions rank among works by such contemporaries as Fred Machetanz and the late Rusty Heurlin.

“Jon Van Zyle is an important Alaskan painter,” Broocks adds. “The quality of his storytelling and visual narrative capture the essence of his setting.”

Jon and wife Charlotte, “who has been known to catch more fish than I,” says the artist.

Countless admirers find affinity with Van Zyle’s hard-edged nostalgia. In 1990, portions of his portfolio were published in Best of Alaska: The Art of Jon Van Zyle, and in 1993, Chronicle Books enlisted him to illustrate The Eyes of the Gray Wolf, an award-winning children’s book by Jonathan London. Van Zyle and London are also collaborating on a bear title, and Little Brown in Boston is publishing a children’s book on caribou illustrated by the artist.

But no project has touched non-Alaskans more than Van Zyle’s artistic record of the Iditarod cross-country dog-sled race from Anchorage to Nome, a dramatic 1,200-mile anachronism left over from the days when Alaska could be traversed only by foot or sled. Since 1977, Van Zyle has been the race’s artistic spokesman.

“Alaska resides in his mind and soul,” says Lowell Thompson, vice president of The Hadley Companies of Minneapolis, publishers of many of Van Zyle’s limited edition prints. “He is part of the Alaskan mystique, and it is a part of him. There’s a close identification with each other.”

Van Zyle delights in the persona of a maverick and demonstrates the feistiness that has made Alaskans resolutely independent. “We don’t necessarily care what Washington D.C. is doing, even though it may affect us,” he says. “It doesn’t mean we don’t pay attention, it’s just that our focus is on being Alaskans first, yet having no pretense about it. That’s what I love about it here — you can be talking to a multi-millionaire on a trail and he’ll be wearing the same jeans and Sorels as you are.”

Charlotte (Zyle’s wife) is depicted in Study Of A Good Fisherwoman.

Traveling much of the year, Jon Van Zyle returns to nature as his artistic provenance: running his dog team across the interior, scouting for grizzlies in Denali National Park, visiting Alaska natives in their traditional camps or listening to yodeling loons from a rustic lakeside cabin. But his favorite pilgrimage is fly-fishing the Kenai with his wife when the river turns red with salmon.

“From as long as I can remember, my image of Jonas a fisherman is that he always catches the biggest fish and always catches the most,” says Daniel Van Zyle, Jon’s identical twin who lives in Honolulu. “He’s a natural. Fish just seem to jump into his boat, while the rest of us have to work at it.”

The metaphor can also be applied to the richness of Van Zyle’s subject matter. He draws his ideas from the wellspring of experience, all of it gathered in the field on hunting and fishing trips or while mushing his Siberian huskies through the tempest of inclement weather. His paintings have meaning through explanations that sometimes cause the artist to choke back emotion.

A few years ago, Jon and a friend who is now deceased made a 300-mile mush through the rugged Denali region and back. His companion left camp early, and when Van Zyle finally caught up to him, he was resting his dog team on a remote bridge. Not wishing to announce his presence, Jon watched through the trees on the top of a hill.

Portrait of a Husky from Van Zyle’s award-winning children s book.

“Within minutes after my friend left, three or four wolves came out from under the bridge where he had been standing. The wolves had been there the whole time and he didn’t know it. The beauty is that his dogs never gave any indication of the wolves’ presence. Wildness can be an arm’s length away, but we may not know it.”

Dan Van Zyle, a successful wildlife painter in his own right, knows what makes his brother tick. For nine months they shared life in their mother’s womb. Their bond to one another is intractable. “It comes down to something very simple,” Dan says. “We came from one seed that divided. I know that when we’re apart for a long time, I feel like there’s something missing and seeing my brother leaves me centered.”

Jon, the elder, was born 23 minutes before his brother on November 9, 1942. Growing up, they had a nomadic childhood with their single mother, Ruth, who bred and raised dogs, and an older but unrelated matriarch, who informally adopted the trio as her own. She is recalled simply as “granny.”

Everywhere the Van Zyles settled — upstate New York, Colorado, Hawaii — it never seemed long enough for Jon to plant permanent roots, but Ruth made sure her boys were exposed to the outdoors and instilled in each a strong conservation ethic. A wing shooter and angler, she also taught that killing was an act considered sacred.

For better than a quarter-century Jon Van Zyle has called Alaska home. His brother, meanwhile, prefers the tropical forests of Hawaii. It is almost like Yin and Yang, the pair of interdependent opposites: one twin magnetized by the crisp vitality of cold-weather environments while the other finds his element in humid heat.

For better than a quarter-century Jon Van Zyle has called Alaska home. His brother, meanwhile, prefers the tropical forests of Hawaii. It is almost like Yin and Yang, the pair of interdependent opposites: one twin magnetized by the crisp vitality of cold-weather environments while the other finds his element in humid heat.

Jon and his wife Charlotte, who has her own publishing business (Alaska Limited Editions), live near Eagle River, a small village twenty miles north of Anchorage. This is suburban living, Alaskan style. Nary a visible footprint of civilization exists between their cedar-sided home and the city. Jon’s studio is surrounded by a birch forest with wandering moose, brown and black bear. Nearby, the couple’s huskies are kenneled, and down a narrow, winding road lies Eagle River, the namesake for their postal address, which runs cold with glacial meltwater.

“We have two main roads near our house,” says Jon. “One going north, the other south. Even if you live in Anchorage, most people find solace knowing that the real Alaska begins only a few blocks from their front doorstep.”

Of course, the real Alaska is close by, beckoning with the lure of a Siren. When the couple first built their home in 1979, a pack of wolves wintered in Eagle River Valley and summered on the other side of a local mountain in the Eklutna Valley. “In the fall the pack would cross over and trail by the house,” Jon says. “I would see them an awful lot when the dogs and I were training.”

Van Zyle’s Campfire Musher relives a moment on the trail, when fire can makethe difference between life and death.

The wolf, he suggests, is probably the most misunderstood creature in the world. “That’s not to say they’re a nice animal, but simply by an error of perception, they have been depicted as evil creatures that kill people . . . which isn’t true. There’s nothing finer than to see a pack of wolves roaming as they have for thousands of years.”

Van Zyle’s legacy is certain to be a posthumous one, in the way that only critical hindsight and nostalgia often meld into one. Historians say his art, while visually enticing, will be coveted in the future for its narrative quality and documentation of a simpler time in a world filling up with people.

Like the late John Clymer who portrayed famous trapper rendezvous, Indian villages and early exploration in the mountainous West, Van Zyle is impassioned with the wild, non-motorized face of Alaska. “It’s the mystery of the land that has become his trademark,” says Susan Ellis, gallery director at Artique Limited, the largest and oldest seller of artwork in Alaska. “He is a charismatic man and a consummate storyteller whose spirit is tied to the wilderness.” When Jon bleeds his heart on canvas, it is the muted color of refracted light and natural tones. Working in acrylics, he produces roughly 50 paintings a year, employing a small palette of only five or six colors, but adding layer after layer of glazes — up to 50 in many paintings — to convey luminescence.

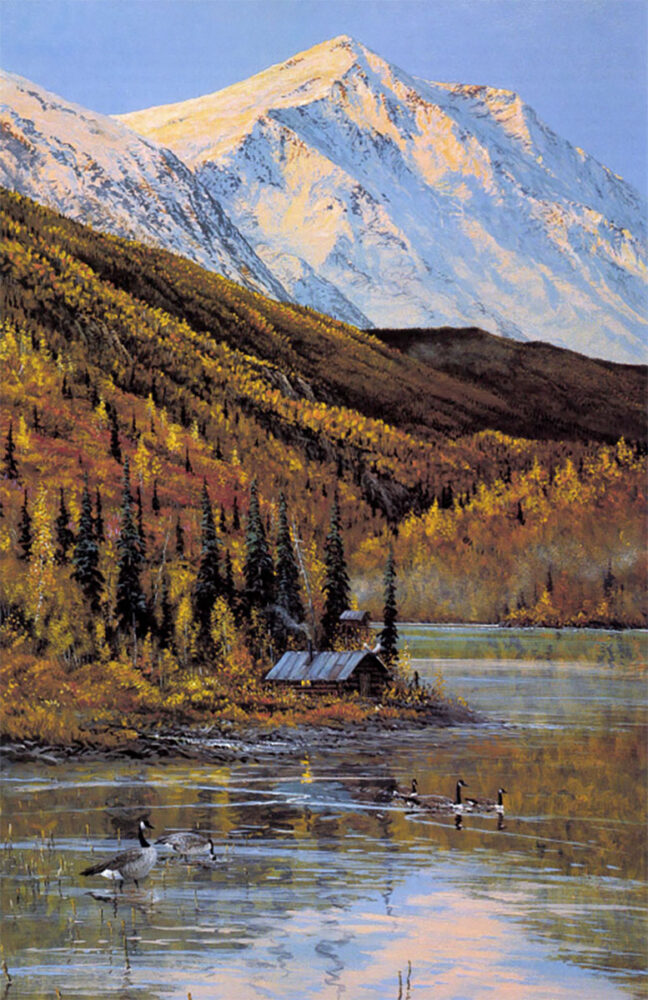

Van Zyle’s Autumn At The Lake captures the beauty and grandeur of Alaska.

“Our colors in the North are cooler compared to those in the south,” he points out. “Our greens are not as green and we certainly don’t have much red. We just don’t have the accents you see in the Lower 48. Strangely, our colors are clearer as opposed to brighter, and they shine their finest contrast at 10 to 50 degrees below zero on a winter night that is 100 percent moonlit.”

The phenomenon, savored as only an Alaskan can, once set the stage or what Van Zyle remembers as “the greatest masterpiece of all.” Near the finish of his first Iditarod in 1976, Jon and his best friend were beating a path into Nome. It was late March, about seven in the evening and the afterglow of sundown was fading fast. In the northern latitudes, as native Alaskans have long attested, the sky is known to play tricks.

“We saw a Devil Dog streak low across the horizon, which seemed to turn on a fantastic display of northern lights,” Jon recalls.

Although the men were losing precious time to the distraction, they remained on the frozen river, their faces locked in astonishment, for another 90 minutes.

“The evening sky was solid northern lights — so intense that it seemed like daylight and so close you felt like you could reach out and touch them. We could even hear them, popping and whistling and banging as they rippled across the sky. The show continued for hours.”

“The evening sky was solid northern lights — so intense that it seemed like daylight and so close you felt like you could reach out and touch them. We could even hear them, popping and whistling and banging as they rippled across the sky. The show continued for hours.”

Jon Van Zyle has never attempted to duplicate the moment on canvas, coveting it in his mind. “I have never seen anything like it before or since,” he says solemnly.” A painting could never live up to it. Some things have to remain yours and only yours, forever. I realize now there has to be some secrets left in life that are never meant to be painted.”

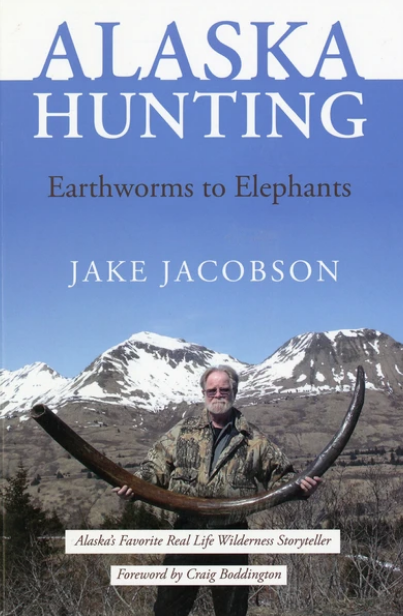

A collection of 39 stories, is intended to be seasoning for a Hunters’ pie, rural Alaska style. Most hunters extol the charismatic mega fauna, but pursuit of lesser game often takes center stage. Occasionally hunting discoveries lead to other endeavors, from jade mining to gold prospecting and fossil recovery. Possibilities are limitless. As we engage in hunting and fishing pursuits memories are laced with the big ones — the exceptional, genetically endowed giants–but some of the brightest memories are of average representatives of their species. What made them so memorable was the combination of circumstances under which they were taken — or lost. Companions, whether human or animal, often make the hunt memorable and its recollections of trophy quality. Buy Now

A collection of 39 stories, is intended to be seasoning for a Hunters’ pie, rural Alaska style. Most hunters extol the charismatic mega fauna, but pursuit of lesser game often takes center stage. Occasionally hunting discoveries lead to other endeavors, from jade mining to gold prospecting and fossil recovery. Possibilities are limitless. As we engage in hunting and fishing pursuits memories are laced with the big ones — the exceptional, genetically endowed giants–but some of the brightest memories are of average representatives of their species. What made them so memorable was the combination of circumstances under which they were taken — or lost. Companions, whether human or animal, often make the hunt memorable and its recollections of trophy quality. Buy Now