This enduring legacy made me wonder how many bipedal hunters had sat on the limestone outcropping from which my guide and I were admiring our long-horned goat. Not just Homo sapiens, but spear-carrying Neanderthals, too.

Spain has been home to ancient beasts, four-legged and two, hunters and hunted, for tens of thousands of years. A rich hunting heritage echoed down that long, steep, stony Spanish arroyo. I was now, happily, a small part of it. And hoping to soon be a successful part of it. “Too big?” I asked my guide, nodding toward this 21st century ram.

Rural exodus has left many small, picturesque villages empty in the stony hills where the author hunted.

“Muy grande?”“Muy grande,” my guide replied, shaking his head slowly. “Medalla de oro.” Gold medal. He shrugged. What are you going to do?

Yes. Of course. Another gold medal Beceite ibex ram. Was it the third or fourth we’d seen that day? It hardly mattered. I’d signed up for a bronze. For an old American deer hunter, bronze, silver and gold trophy designations take some getting used to. But this is the Spanish system for pricing hunts. The larger the horns, the older the ram. The older the ram, the rarer the ram. The rarer the ram, the higher the price. I may have been hunting in a land of antiquity, but that didn’t mean I could afford a ram of antiquity.

“Let’s go find a little one,” I sighed.

“Little one,” as you might guess, is a relative term. To a first-time Beceite ibex hunter, a bronze-class ram looks muy grande. Its heavily ridged, slightly flattened horns rise 28 to 30 inches in a flaring, curving sweep designed to inspire an artist. To know that such a graceful form is merely the result of form fitting function—the violent, utilitarian function of beating (literally) your competition to breeding rights—makes these horns all the more intriguing and elegant.

Seeing one of these battered, hard-fighting, old-world goats with horns still intact makes it easier to understand how the North American mountain goat is not a goat at all, it’s scrawny, chamois-like stilettos much too fragile for head-to-head competition.

Seeing one of these battered, hard-fighting, old-world goats with horns still intact makes it easier to understand how the North American mountain goat is not a goat at all, it’s scrawny, chamois-like stilettos much too fragile for head-to-head competition.

I’d gone to Spain in early December with my wife and several friends at the invitation of Linda Powell, marketing manager for Mossberg firearms. She’d found the hunt through Tony Caggiano of World Slam Adventures. He was along for the fun, too. We were all under the excellent guidance of Vicente Gil of Caza Hispanica. Vicente knew English much better than I knew Spanish, but he’d hired lively, multilingual Ionella Scoarta to interpret for all of us. That gave us deeper insights into the land and its people. The hunting itself needed little verbal communication. Hike, glass, sneak, shoot. But shoot only the correct ram! There were those metallic restrictions complicating the hunt.

We weren’t an hour into the hunt when I spotted my first ibex, a ram atop a cedar-lined ridge, its towering, gold-medal horns sweeping the sky. My desire was immediately kindled. But unquenched.

“No, no senior, too grande!”

So no stalk. But I at least had an upper end benchmark. And that soon prevented me from shooting the wrong ibex . . .

Within an hour of leaving the gold medal goat to his castle in the air, my guide gestured excitedly toward another, pointing, ducking and pantomiming “shoot.” This ram walked below us, skipping over the stacked stone wall of an old terrace, stopping broadside to stare back, not more than 200 yards out. A tempting target. But I hesitated because the horns looked too big. Not the equal of the gold medal, but getting close.

Did my guide actually want me to shoot this one? Or was something being lost in translation? His body language and eager eyes said shoot, but the horn length on this ibex said “silver.” As in “dig deep for more silver because you’ve just upgraded from bronze.”

Complicating all this was the fact that this guide was a last minute stand-in for the regular guide who’d had a family emergency. There was a good chance this gentleman didn’t know I was a bronze-level hunter. I didn’t want to get both of us in trouble, so instead of shooting the ram with my Mossberg Revere, I shot it with my camera. The pictures later proved that, had I unleashed a round, I’d have been the proud owner of a silver medal ram and a bill to match.

After that near calamity, we prowled deeper into the steep-sided canyons, their woodland edges littered with bold black-and-white signs. I assumed they forbade hunting, and I was partly right. The signs announced restrictions on the hunting of truffles. Such is the demand for these subterranean fruiting fungi that harvest is strictly controlled by season dates, limited entry units and similar procedures familiar to trophy sheep hunters.

The flared horns of this black-bellied ibex ram identify it as a gold medal warrior secure on the ledges that have sheltered it and its ancestors for hundreds of thousands of years.

We encountered a dog and its mushroom hunting master who proudly displayed a double handful of what appeared to be brown stones, perhaps dried animal droppings. No, they were the gastronomically famous Teruel black truffles with a value of about $500. Not a bad morning’s work. Clearly we were hunting the wrong species.

Little did I know I would taste those truffles that evening during a private dinner at Restaurante Asador in nearby Puertomingalvo. Linda, Tony and Vicente had set it up. And our personal chef for the five-course meal was none other than my morning’s substitute guide. Spanish ibex hunting springs all kinds of surprises on the unsuspecting, unsophisticated American.

Thanks in no small part to wine connoisseur Linda and gourmand Tony, fine dining was an integral part of this adventure. From fine restaurants near the famous orange groves surrounding Valencia to seaside “crab shacks” in Peñíscola to elaborate custom dinners at our rural lodge Mas de Cebrián, we ate to a standard I’ve rarely tasted on any goat or sheep hunt in North America. It was like lodging at the Flying B in Idaho while hunting Dall’s rams in the Brooks Range.

It wasn’t that I didn’t expect to find ibex in a harsh, rocky land. I just didn’t expect to find such a harsh, rocky land. Not in long-civilized Spain, once the wealthiest, most powerful nation in Europe, if not the world.

Gastronomically famous Teruel black truffles have a value of about $500.

Despite extensive reforestation efforts in the past 40 years, the hills we hunted near Mosqueruela appeared to have been stripped of their wealth or, as western cowpunchers might say, “rode hard and put up wet.” Battered, scraped and scoured by thousands of years of too many sheep, goats and cattle, much of its topsoil seems to have migrated to the Mediterranean Sea. Most of its people have migrated to cities.

Chalkstone bedrock litters the land like broken bones, many of them long ago stacked in walls that stair-step up steep canyon slopes, hugging remnant strips of soil, some barely large enough to harbor a single fruit tree.

A testament to hunger, stone houses and barns stand empty, entire villages abandoned. From all appearances, humans have worn this part of Spain’s fingers to the bone. But not its ibex. These goats seem well adapted to survive, even thrive in this dry, desiccated land.

The fees charged to hunt ibex provide welcomed support for local communities, jobs for guides and cooks and lodge staff. Now that ibex are the goat that lays the golden eggs, they are revered and protected as an enduring native animal and sustainable source of protein and income.

It being the rutting season, we saw plenty of signs of ram fights. We heard horns clash in the pine and oak woods. We saw dust rising from the battle grounds, glimpsed unsuccessful challengers being run out of town. For a rather short-legged, stocky, rock-climbing goat, the ibex is surprisingly fleet.

One afternoon, a truffle hunter and his dog jumped a silver medal ram that raced directly at us on a steep, stony rocky slope, gobbling up ground in swift, graceful bounds, passing beneath us at easy handgun range and putting our hearts—or at least mine—in our throats.

“Vamanose!” my guide said, skimming one palm over the other. This was my regular guide, not our chef, and we were in a new series of canyons he seemed to know well. We ghosted the rim, ducking to the edge every 100 yards or so. The sun was setting and ibex were rising, walking, foraging. Stones clanked and clacked.

There. Near the bottom. A nervous band. Three ewes. No six. And two young males picking their way up the far side. One ram was noticeably larger than the other. I bellied into my pack, nestled the lovely walnut stock atop it, found the bigger ram in the scope, and asked my guide if I was cleared to take the “grande” of the two.

“Si. Grande.”

I judged the ram within point-blank-range of my 6.5 Creedmoor. I turned the Swarovski to 8X, leaving room for a swinging lead if that became necessary, held mid-shoulder and fired. The ram stumbled just before the slap of the strike bounced back. An insurance shot anchored him.

Had Spomer shot this ram as his replacement guide had urged, he would have been reaching for more silver.

Despite a straight-line distance of just 265 yards, we climbed down, over and around several rock terraces before reaching the ram. I could smell it before seeing it. Like domestic goats, ibex rams anoint themselves with urine, spraying it liberally on their bellies, neck, faces and horns. Various scent glands on the head probably add to the distinctive aroma. Keeping this oily stench off the meat while skinning is an art form perfected through caution and long experience. I let my guide demonstrate. Thoroughly cleaned and de-scented, Beceite rams with their black vests, goatees, bellies and legs make beautiful mounts.

With that my day was over, but not my ibex hunt. Linda had fallen ill with the flu. Vicente explained that her ibex tag was good for anyone else in our crew. I drew the long straw. Vicente and I went looking, glassing terrace-lined canyons, crumbling farmsteads and the blue-domed Church of Our Lady de la Estrelle cathedral in a virtual ghost town on the banks of the Monleon River. We peeked into caves where revolutionaries had sheltered during Spain’s civil war. I wondered if Hemingway had driven any of these trails. And then we found a ram. Solid bronze. Entertaining nine ewes and lambs high up in a brushy bowl.

Vicente nodded upward. I shouldered my rifle. We started the ascent, keeping under the oaks. As we climbed, four of the ewes wandered off, but our quarry stood over the bedded five that remained.

The winds were strong and swirling when we reached a sharp bend in the draw where the cover thinned. This was as near as we’d get. Neither of us had remembered a rangefinder.

I did some rough MOA comparisons with the Z5s reticle and decided that 350 yards was about right, then stuck my finger into the breeze. It cooled alternately left, right and forward. Classic orthographic lift and funneling. A strong updraft countered a slightly stronger downdraft. Leaves nearest the goats flapped steadily right to left. Those by us were driven left to right. I did the math, threw it out and went with my gut.

“Where’d he go? Where’d he go?” I asked uselessly after the shot. I bolted home a second round and was sorting through the dust and fleeing ewes. I could see no horns. Vicente couldn’t understand my English. I turned and raised my palms. “Where’s the ram?”

Vicente was one big grin. He slapped me on the shoulder. “Bueno! Bueno!”

I’d anchored the ram right there. My shot had landed three inches right and about that many higher than I’d held for, striking the spine. Minute of ram. Close enough. I had cemented my membership in the ancient club of Beceite ibex hunters on the Iberian Peninsula. It was an honor.

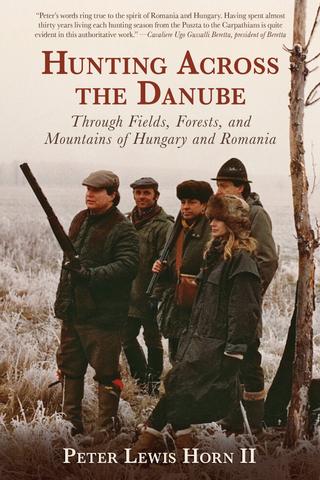

This fascinating book explores a sporting paradise in Eastern Europe. It covers a variety of game, from stag and boar to grouse and ducks. With the latest facts about the best hunting areas, seasons, firearms and equipment, this book should awaken an appreciation for all the best that Hungary and Romania can offer sportsmen. Buy Now

This fascinating book explores a sporting paradise in Eastern Europe. It covers a variety of game, from stag and boar to grouse and ducks. With the latest facts about the best hunting areas, seasons, firearms and equipment, this book should awaken an appreciation for all the best that Hungary and Romania can offer sportsmen. Buy Now