The old man holds my hand in a frosty grip. But his weak, raspy voice and eyes warmly thank me for being his friend for almost 50 years. Staring past his fish tank and sagging shelves of sporting books through a window and into the far distance, he silently raises his other hand to show three fingers. I guess what they mean. “Three days?” I ask. His skeletal head nods a slow “yes,” indicating that he’s made up his mind. And I realize that my journey with him—one that began five years before we founded Sporting Classics in 1981—was coming to an end.

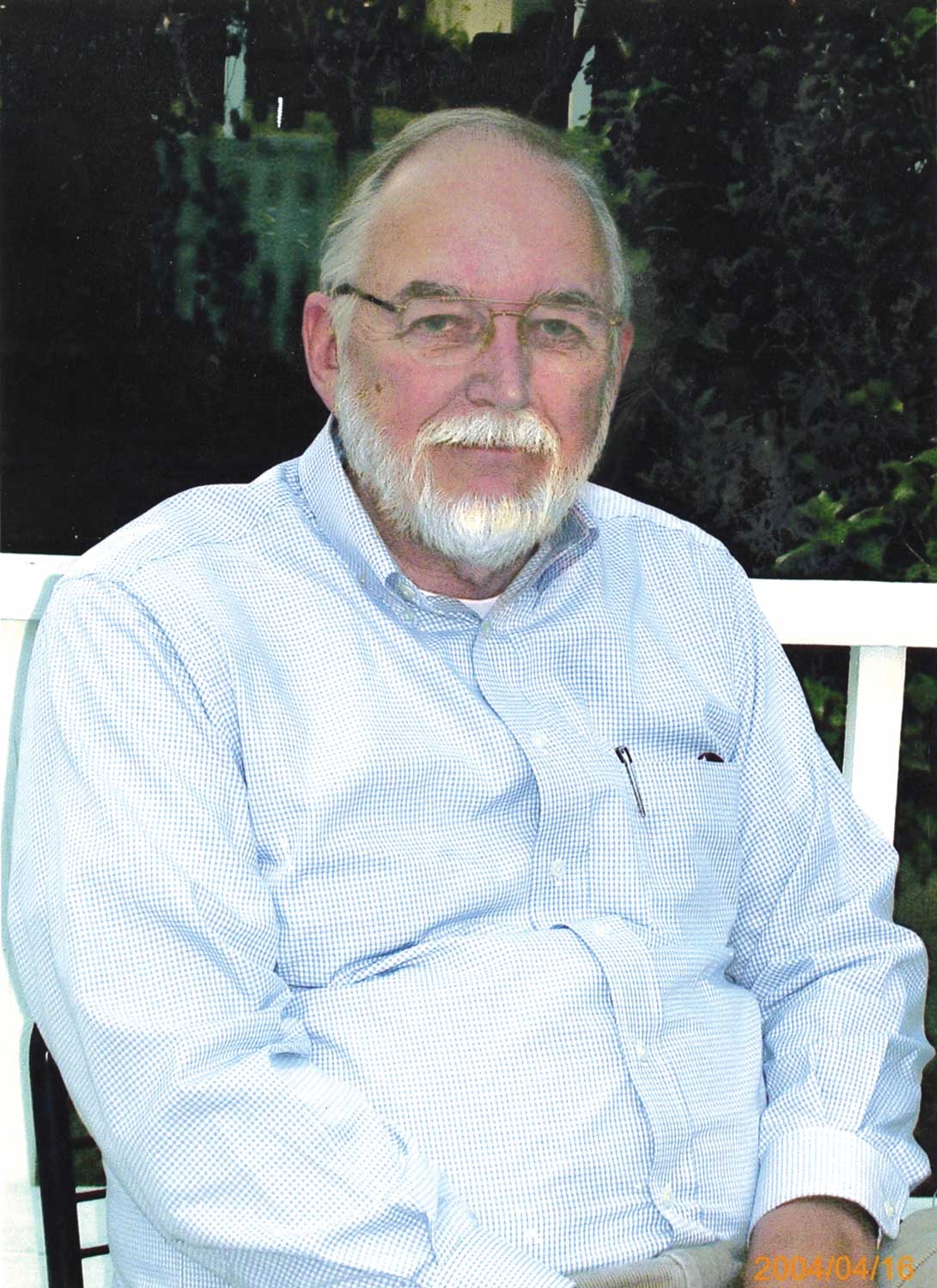

By the time you read this, former partner, friend and one of my heroes, John Culler, will already have arrived in Tinkhamtown, Corey Ford’s imaginary place where an old bird hunter stops to rest. Forever.

John was born in Macon, Georgia, in 1937, but grew up in Smithville, “God’s Country,” he always called it. He was raised by his mother and maternal grandparents; his biological father having left them when he was an infant. Something about that often casts people from a different mold, and it certainly did John. Never a financial wiz (he would not lower himself to worry much about money), he was otherwise brilliant, confidant, fearless and charismatic. Those last characteristics, combined with a huge appetite for books and magazines, would later help him better understand the world of publishing and exactly what kind of stories sportsmen wanted to read and enjoy.

After a stint at Valdosta State University on a baseball scholarship, John worked as a journalist and sportswriter for several Georgia newspapers. But he loved everything about hunting and fishing, from the idea of hunters as conservationists, to the literature, to the experiences, so he took a position as public information officer for the Georgia Game and Fish Commission. There, he honed his already substantial speech-giving ability regarding wildlife, habitat and conservation.

After a stint at Valdosta State University on a baseball scholarship, John worked as a journalist and sportswriter for several Georgia newspapers. But he loved everything about hunting and fishing, from the idea of hunters as conservationists, to the literature, to the experiences, so he took a position as public information officer for the Georgia Game and Fish Commission. There, he honed his already substantial speech-giving ability regarding wildlife, habitat and conservation.

I met John Culler at the South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Department, where he was the Information and Public Affairs division director and editor of South Carolina Wildlife magazine. I was hired in 1976 to work on the department’s special publications. After I learned the intricacies of the direct mail business from our consultant, John asked me to take over producing the magazine’s promotional materials. Since I was working full time in the position I already held, and attending graduate school in the evenings, it was a handful, but it was an incredibly valuable learning experience. Surprisingly, in 1978, John gave me the opportunity to write my first magazine story based on a concept that I’d suggested in an editorial meeting. I was ecstatic, though I wondered whether he had more faith in my ability than I did.

While he was editor, South Carolina Wildlife won The American Association of Conservation Information’s Best State Conservation Magazine (among all U. S. conservation magazines) an almost embarrassing number of times.

John also received a Conservation Communications Award from the South Carolina Wildlife Federation and the National Wildlife Federation for Outstanding Contributions to the Wise Use and Management of the Nation’s Natural Resources.

John thought bigger and dreamed bigger than anyone I’d ever met. And I was fascinated by his supreme confidence. Besides, he loved hunting bobwhites as much as me. Having grown up under similar circumstances, he and I “gee-hawed” from day one. We hunted, fished and worked together for three years. Then, in 1979, John got his “opportunity of a lifetime” and left South Carolina and South Carolina Wildlife to become editor of Outdoor Life in New York. He came home about once every month and we remained close friends.

In late 1980, John asked me about joining the Outdoor Life staff, so I went up and stayed with him a few days to see what New York had to offer. I enjoyed the visit, but I could sense something was amiss. He didn’t really say it, but I could tell he missed his wife and school-aged children who were back home in Camden, South Carolina. I knew that I’d have felt the same, so I declined his offer. Oddly, he didn’t seem disappointed. Instead, he asked me to meet him north of Camden the following weekend to fish for bass and talk about our future.

There, on the black magic waters of Henry Savage’s pond, surrounded by majestic, moss-shrouded hardwoods and gigantic gray boulders, we caught bass and discussed our dream to publish the very best outdoor magazine ever. He titled it Sporting Classics.

I don’t remember us catching anything of significant size that day, but I do remember beginning to form the words describing our mission. We would: Preserve the heritage, the romance, the art of hunting and fishing. We’d keep relevant all the great artists, authors and craftsmen from the past while discovering new ones for the future. That spring, we began working on it.

Sporting Classics was born in August of 1981. Ogden Pleissner’s The Blue Boat on the St. Anne, graced the cover. By the time it hit newsstands, we’d moved on to the next issue, then the next. Bill Webster at Wild Wings helped us with advertising and lists of buyers. Many others, such as Bubba Wood at Collector’s Covey and Doug Mauldin at Delta Arms helped as well.

In addition to being a talented writer, John was a superb salesman. However, what I found most valuable about working with him was that he was inspirational. He encouraged his children, employees and partners to “think big,” and to do their very best.

For ten years, we published our dreams. Joined in our effort by Art Carter, another great friend of John and me, we traveled the world, hunting and fishing its best places. We launched Premier Press Books with the help of professor Jim Casada, republishing the best outdoor books ever written, bound in leather with real marbled endpapers. We created Masters of The Wild, unique books featuring the very best sporting and wildlife artists alive at the time.

Little known and very rare books by long-forgotten authors found their way into our 27 leather-bound book series titled, The African Collection. And all along we interviewed the finest sporting craftsmen and met with some of the most influential outdoorsmen for stories that appeared in the pages of Sporting Classics. Art and I fished Alaska with Ted Williams the famous baseball player, and I fished with Ray Scott at his home in Alabama.

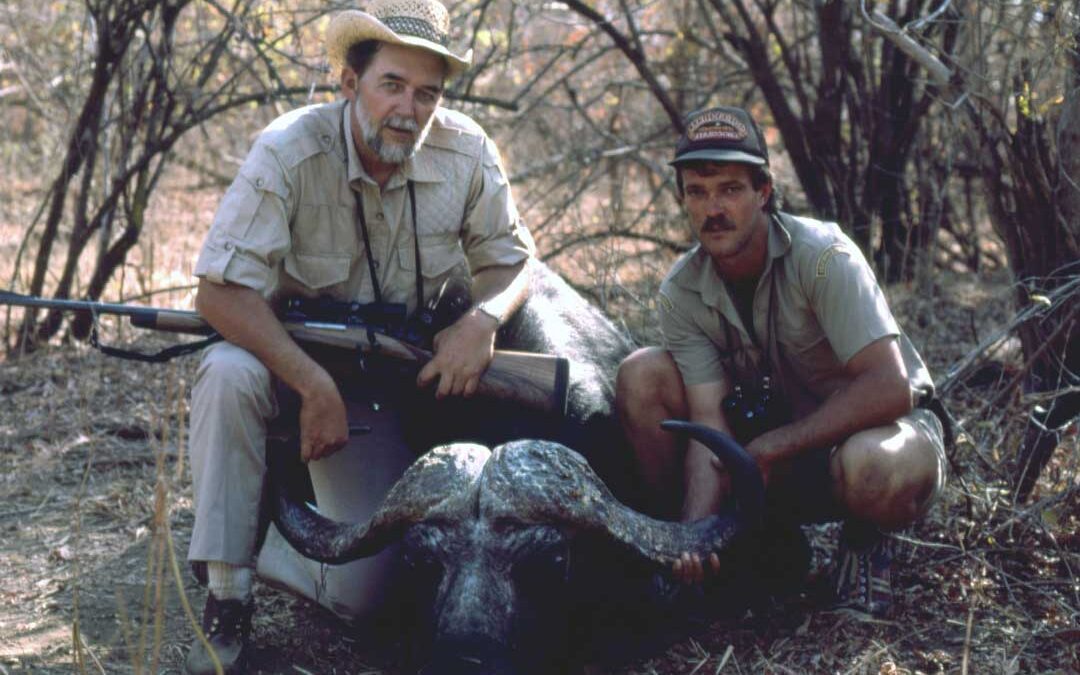

Chuck Wechsler, who served as Sporting Classics’ editor for more than 30 years, has many fond memories of John and his multitude of attributes. Foremost among them are two experiences from their ten-day safari at Devuli Ranch in Zimbabwe in 1987.

“The word ‘resolve’ comes to mind when I think back on that hunt,” says Chuck. “On our second morning, we spotted a herd of zebras led by a big stallion. I followed John and our PH as they slipped through the thornbush to get within a hundred yards of the animals. I watched John raise his .375 and almost casually fire an offhand shot. The bullet grazed the zebra’s chest and he bolted away with the rest of the herd.

“We followed the wounded animal for at least four miles before we were able to edge close enough for a second shot. But this time, the distance had to be in the neighborhood of 250 yards, with the zebra slowly quartering away from us. Standing behind John with my camera, I observed a completely different shooter who was focusing with singular intensity on his target. Obviously, John was determined to drop the zebra in his tracks. Which is exactly what happened.

“Two days later, I once again witnessed not only John’s resolve, but his courage and determination in a dicey situation. We had located a group of Cape buffalo feeding in a dry riverbed, what the natives refer to as a wadi. John and the PH stalked to within 50 yards of a monster bull that stood facing them in the sandy river-bottom. John fired, sending a 300-grain bullet into the center of the animal’s chest. At the shot, the bull whipped around and pounded up the ten-foot embankment and into the thick brush along the wadi.

“The PH turned to John and said: ‘You hit ’em good, but I need to make sure. This could be dangerous! Stay here while I check on him.’

“‘No, I’m going with you,’ John responded. ‘I shot him and it’s up to me to finish the job.’

“I watched the men as side-by-side they slipped up the dirt bank. Peering over the top, they spotted the bull less than 20 yards away, just as it emitted a loud death bellow and slumped to the ground.

“Back at camp, John recalled: ‘That death bellow was one of the most beautiful sounds I’ve ever heard.’”

Since I was working extremely long hours, including weekends and holidays, commuting from Columbia 30 miles away, many days John invited me to eat breakfast and dinner with him and his nurse wife, Linda, at their home in Camden.

On the other hand, the excitement, job satisfaction and pride of what we were doing was palpable. Our friends and families were jealous. Of course, we were always hindered by a lack of financial resources, which prevented us from undertaking many opportunities. So, twice John sought outside investors. In both cases, however, their money was too little and too late. And from my perspective, it just created more turmoil in not knowing who was making the final business decisions.

Recently married, I realized that I needed to work on my own financial future. So, in the mid-1980s, I began doing more and more freelance advertising and direct mail work. That effort grew into a small ad agency.

By the early ’90s, that advertising work reached a point where I did not have to rely on my tiny, infrequent Sporting Classics salary to survive. And when the last group of magazine investors demanded their money back or they planned to sell it, I was able to step up and plunk down the cash needed to fix things. However, it also meant that I’d have to trade my part of the two other publishing companies that John and I owned for his part of Sporting Classics. Though it was not easy, he and I agreed to go our separate ways. That was more than 30 years ago. There were plenty of hurt feelings from other staff members, but John and I never let money get in the way of our friendship. It was too important for both of us. So, we still hunted, fished and talked about business at every opportunity.

In 2019, John’s now retired wife of 63 years, Linda, passed away at 79. It would have been traumatic regardless, but because she was such a wonderful, giving wife, friend and mother to his five children, it was even harder on him. She’d stood by him through thick and thin. After that, with every visit, I could see a small decline in John.

In 2019, John’s now retired wife of 63 years, Linda, passed away at 79. It would have been traumatic regardless, but because she was such a wonderful, giving wife, friend and mother to his five children, it was even harder on him. She’d stood by him through thick and thin. After that, with every visit, I could see a small decline in John.

Following is one of the last paragraphs from “The Road to Tinkhamtown,” one of John’s favorite stories:

He could see it all now: the warm October sunlight, the ground strewn with freshly-pecked apples, the dog standing immobile with one foreleg drawn up, his back level and his tail a white plume. Only his flanks quivered a little, and a string of slobber dangled from his jowls. “Steady, boy,” he murmured as he moved up behind him, “I’m coming.”

This magazine was John Culler’s idea. He was one of those creative geniuses who plays by a different set of rules. Perhaps intolerable to some. But even to this day, inspirational to those of us who knew him well. He and Linda were buried near his grandparents’ home in Smithville.

Wherever you are John, I hope there are quail, deer, bass and bird dogs… maybe a kudu or two… and plenty of exciting hunting and fishing stories to read.

Your friend,

Duncan