John Clymer was a painting phenomenon.

None of his contemporary artists even came close to achieving the kind of success Clymer enjoyed with his history and wildlife paintings. Toward the end of his life, collectors were happily standing in line to pay $300,000 for one of his colorful oils.

A quiet, gentle man, modest and unassuming, Clymer was sixty-two when he quit the commercial art world to paint the subjects he liked best — North American game animals and Western history. He had his first one-man show at Grand Central Art Galleries in New York City in 1966, and from that time forward he was never able to keep up with the demand for his work. By the1970s, Clymer was painting principally for just two Western art exhibitions, and his rise to fame and fortune through these venues was nothing short of spectacular.

Prior to 1970, Clymer priced his paintings in the $4,000-$6,000 range. Then, beginning in 1972, he won gold medals five years in a row at either the National Academy of Western Art (NAWA) show in Oklahoma City or the Cowboy Art exhibition in Phoenix, and his prices started climbing. In 1973, his painting Whiskey, Whiskey (which Clymer described as “a small group of trappers … whooping into a Green River rendezvous … lured on by the sight of whiskey and old friends”) brought an unprecedented $15,000.

The next year Clymer entered two exceptional paintings, Sacajawea and Alouette, in the NAWA show at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame. The latter brought $17,000 and resulted in a personal injury suit against the Cowboy Hall of Fame, filed by a collector who injured herself as she raced to be the first to reach Clymer’s paintings. No matter the five-figure price, a Clymer canvas was still a bargain and every Western art collector wanted one. In Phoenix, a fist fight threatened to break out at a Cowboy Art show when seventy people lined up to buy Clymer’s Nez Perce, 1877 priced at $20,000.

The big shows changed their sales format and began drawing names to protect would-be buyers from maiming themselves as they scrambled for Clymer’s art, and up and up went his prices. One painting purchased for $18,000 at the NAWA show in 1977 changed hands twice more before the weekend was out. And there were times in Phoenix when the drawee would openly try to sell his Clymer for a profit immediately after hearing his name called. The last of the modest-priced Clymers was The Boys at Bent ‘s Fort, which sold for $38,000 at the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1979.In 1981 two Clymer entries at the Cowboy Artist’s show brought $125,000and $150,000.

Critics and peers compared John Clymer to Remington and Russell, and Clymer himself was amazed at the prices his paintings commanded. But he was never in any sense an overnight sensation. Though arguably the most financially successful artist in the history of Western art, the fact was he had climbed to the top, step by hard step. Younger painters admired and envied him, but they lacked his experience, both in the art world and in life. A small, humble man, Clymer was one of the lucky ones who achieved his boyhood dreams through hard work and stick-to-it-iveness.

A small-town lad who remained close to his roots, John Clymer was born in 1907, in Ellensburg, Washington, on the east slope of the Cascade Mountains, where he grew up with a love of the hills and the outdoors. He liked to draw, and he studied the work of top magazine illustrators. Clymer wanted to remain in the mountains, and he reasoned that he could become a successful illustrator no matter where he lived.

As a high school freshman, Clymer signed up for correspondence art lessons with the Federal Schools of Minneapolis (later Art Instruction Schools). Soon he had a job doing window displays for the local rodeo in Ellensburg. A couple of years later, after buying a woodsman’s Colt pistol, he sold two pen-and-ink drawings of the gun to Colt Firearms for use in their national advertising, including the cover of Triple X magazine. It was his first commercial sale.

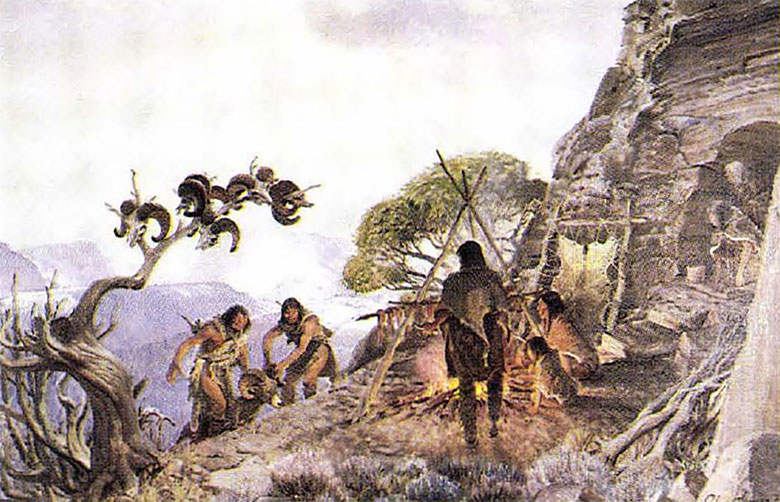

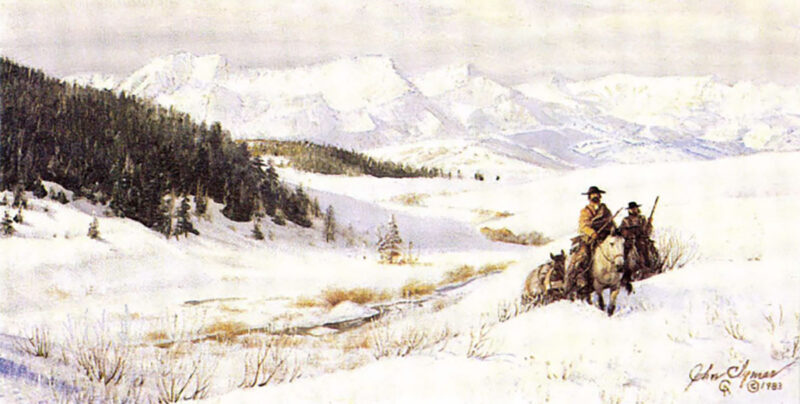

After Remington and Russell, it was John Clymer’s turn to document the history of the American West with dramatic recreations of early trappers, explorers and Indians. Entitled World of Snow, this painting is among a number of original works at the Clymer Museum & Gallery 20 in Ellensburg, Washington.

Never one to waste time, the week following graduation from high school, Clymer found work as an illustrator for a mail-order catalog in Vancouver, British Columbia. Always eager to improve his skills, he took art classes at night, studying at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts with Fred Varley, one of the well-known “Group of Seven.” During the prosperous late 1920s, he had more illustration work than he could handle from Canadian magazines.

In 1930, Clymer’s never-ending pursuit of excellence brought him to the Wilmington Academy of Art (the old Howard Pyle school) in Wilmington, Delaware. Frank Schoonover was still teaching there, and Clymer met N.C. Wyeth, the man he credited with being the single greatest influence on his career. For a year and a half, he consulted regularly with Wyeth, and like Wyeth, he began setting aside every Saturday for study.

“I patterned my life after N.C. Wyeth,” Clymer said. “I did not study with him. He didn’t have students. Your greatest teachers are your friends that help you.”

Clymer married his high-school sweetheart, Doris Schnebly, in 1932, but he wasn’t ready to try his artistic wings in this country. With the United States suffering through the worst year of the Great Depression, and art jobs hard to come by, Clymer and his bride returned to Canada where he took up where he had left off as an illustrator. He also exhibited his paintings with the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Art.

In 1936, Clymer returned to the United States, intending to stay only temporarily. He had gone to New York to study with Harvey Dunn at the Grand Central Art School, but he soon bought a home in Westport to be near the New York art market During the next thirty years he made a good living as an illustrator for magazines and commercial accounts. His work appeared in numerous magazines including Field and Stream, True, American Sportsman, Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping; and he did advertisements for Chrysler and other high-buck accounts.

During World War II Clymer and his close friend, cowboy artist Tom Lovell, joined the Marine Corps, and the two men became the official illustrators for Leatherneck and the Marine Corps Gazette. At the war’s end, he returned to commercial illustration. His best-known works from this period are the more than 80 Saturday Evening Post covers depicting the American scene he painted between 1947 and 1962. Every summer he and Doris traveled west, studying the early history of the places they visited. Clymer always credited his wife for urging him to paint historical subjects.

When Clymer finally quit New York and commercial art to devote himself to easel painting, the couple moved back to the West, this time to Teton Village near Jackson Hole in Wyoming, where they built a home and studio in 1970. Teton Village is snowed in six months of the year, which suited Clymer just fine. During the long winters he could paint steadily every day and evening with little interruption. In the summers, he and Doris systematically followed the trails of the early pioneers, gathering material for the paintings that were catapulting Clymer into American art history.

In 1976, Northland Press in Flagstaff, Arizona, published John Clymer: An artist’s rendezvous with the frontier west by Walt Reed. The trade edition came out at $40 and today sells for about $60. There was also a special leather-bound edition, limited to 61 copies, each containing an original drawing. Clymer did the drawings with a ballpoint pen and gave them to the publisher who bound them into the books. The special edition copies originally sold for $500 and were all spoken for prior to publication.

Since Clymer’s death in 1989, residents in Ellensburg, Washington, along with friends and relatives of the Clymers, have helped establish the Clymer Museum and Gallery in the artists’ hometown. In addition to a permanent Clymer collection and memorabilia, the museum mounts changing exhibits featuring contemporary artists whose goals parallel those of John Clymer in portraying and celebrating our western and natural heritage.

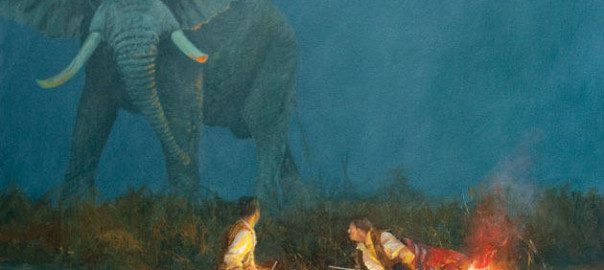

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now