It seems ironic that Jim Kasper would look at any painter’s life with envy.

It would only seem natural to assume that the prime source of inspiration for an animal artist would be, well, animals. And Minnesota artist Jim Kasper has indeed been inspired by a host of furred and feathered creatures: handsome whitetail bucks, strutting spring gobblers, bugling bull elk….

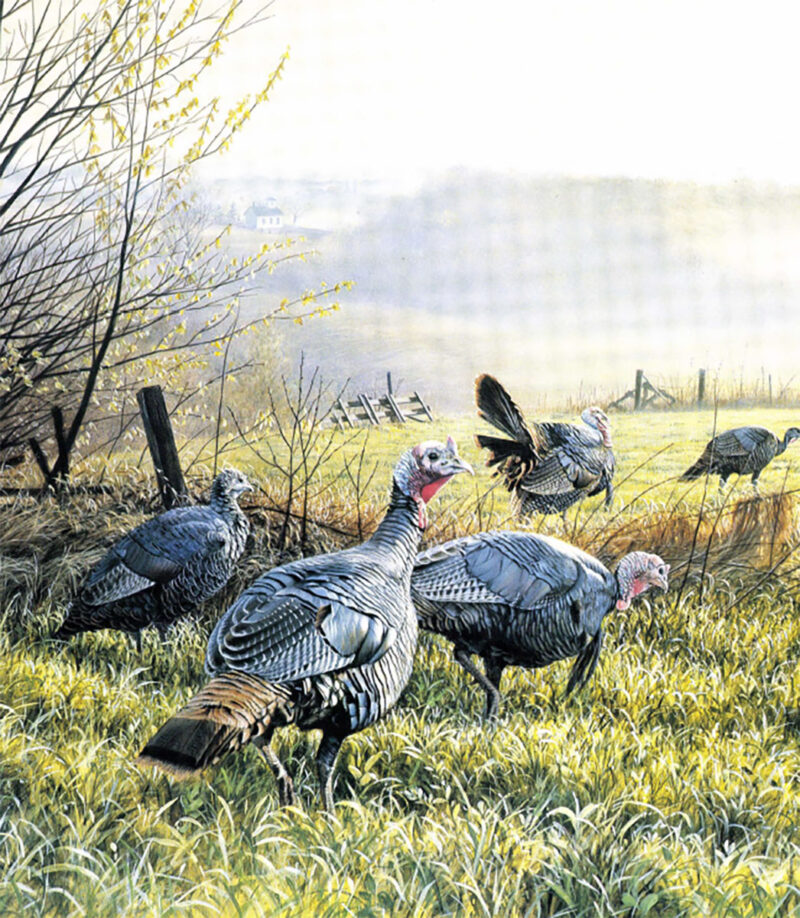

Fenceline Crossing — Wild Turkeys

But says Kasper: “The importance of landscape is as crucial to the success of a painting as the animal itself. Not only must today’s wildlife paintings show a much more complete picture of the animal’s habitat, but how it lives in that habitat. I hear this from buyers all the time; they connect emotionally with a scene because it reminds them of a farm acreage, a hunting camp or a wild area important to them, and they want the painting because of that. And to me, those sales are the most satisfying of all.” Creating these sentimental connections is something that Jim Kasper understands all too well. During a midwinter visit at his northern Minnesota home/studio, we discussed several of his favorite paintings and their backgrounds. The factor that moved Kasper to paint nearly all of them? You guessed it: landscape. Take his successful painting Fenceline Crossing.

“I was on a research trip for turkeys and I’d fought lousy weather for several days,” Jim recalls. “When the weather finally broke, I was driving past a beautiful little spot when I saw this really unique lighting situation and I just had to stop and photograph it. When the slides came back I knew I had to paint that scene — and when I did, it just flowed.” Indeed, Jim’s love for wild country reaches back to childhood. Growing up near St. Michael, Minnesota, he enjoyed an easy walk to the nearby Crow River. The inquisitive youngster took to poking along the river bottom, collecting a feather here, a unique rock there, gradually falling under the spell of the natural world. “I was an explorer as far back as I can remember,” Jim says. “I would get home and immediately head out to the woods. I didn’t mind being alone and I had no one to answer to. I guess I was different that way; I never needed other kids to be entertained.”

Kasper’s childhood wanderings blossomed into a sporting life he enjoys to this day His love for Minnesota’s wild places took a vacation after adolescence, however.” In my late teens and early twenties, I felt there had to be a better place than Minnesota,” he laughs. After high school he entered the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, studying graphic design and illustration, a career that would allow him to escape the state. Upon graduation he took a job with Hallmark Cards, who moved him to their creative headquarters in Kansas City, Missouri. The time away from Minnesota eventually wore on Jim, and by 1968he realized it “was a pretty good place after all.”

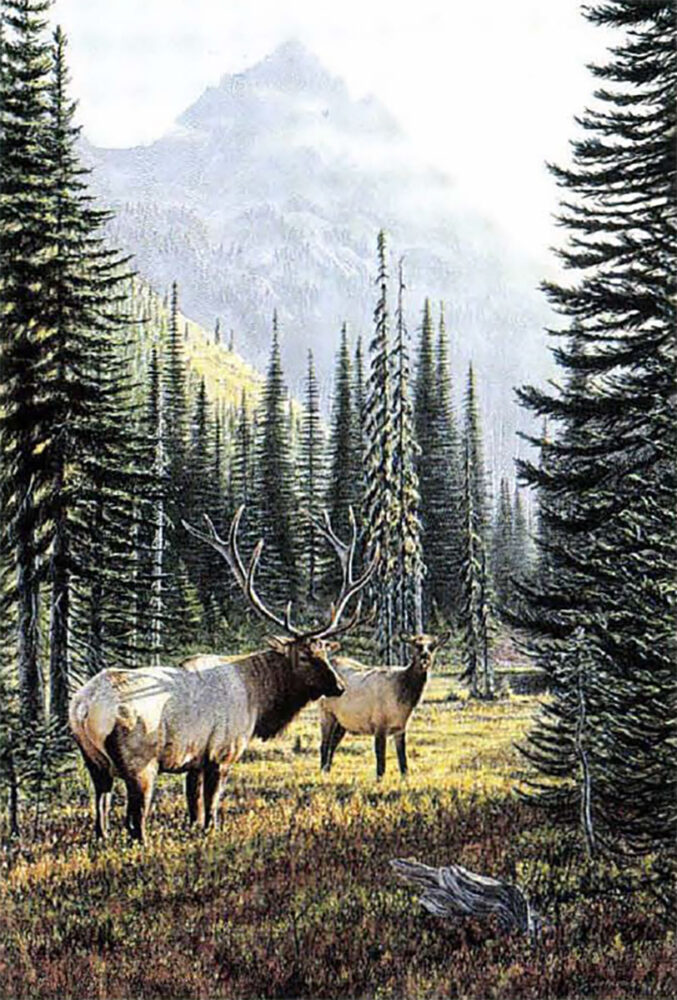

Out of the Shadows shows two elk emerging from the dark timber into a meadow bathed in early morning light — a time and place that any elk hunter can relate to.

Though he had returned home, Jim still hadn’t found his niche as an artist. He continued to work in design and illustration while painting in his spare time. Splitting his creative energy proved exhausting, Kasper remembers. “I came home with a mind so full of unsolved problems that I was just broken; I had nothing to give, only a tremendous desire to paint.”

Broken or not, Jim’s wildlife paintings were good enough to attract an audience, and by 1981 he was selling enough limited-edition prints to launch his career in wildlife art. “I was amazed at my progress once I began painting fulltime. My palette improved and expanded, and just my physical dexterity in painting was so much better. By dedicating my best mental effort to it, I saw a great improvement in just a few short months.”

Others noted Kasper’s coming of age. In 1985, the Minnesota Deer Hunters Association selected him as their artist of the year (an honor he would receive again in 1989), and Wild Wings approached him about publishing his originals. Before long the hard-working artist emerged as a bright star in Wild Wings stable of talented painters, and Jim says he appreciates the aggressive marketing and support the publisher continues to provide. ” I burned the candle at both ends for too many years to promote myself,” he stresses. “I knew I didn’t want that.”

Kasper’s images of white-tailed deer proved especially popular with Wild Wings buyers. To date, he’s published 13 paintings of whitetails, and admits they provide a constant source of inspiration. “I just love the form of a whitetail,” Jim enthuses. “The way the light falls on their shape and the way they move; it’s so inspiring, almost like a dancer.”

Chance Encounters reflects Kasper’s passion for documenting the many complexities of deer behavior and his love for the whitetail’s form and movements. Here, a swollen-necked buck displays some lordly interest in several does.

A veteran of many hunts with gun and bow and a tireless observer of whitetails (his backyard feeders attracted seven deer as our conversation carried into the evening), Jim explained that the complexities of whitetail behavior and physiology open up limitless ideas for future paintings. “My challenge now, after doing so many deer pieces, is to create something new, show some aspect of deer behavior not commonly seen: rutting activity, does sparring, animals in spring coats and settings — all are ideas that I’ve had, though some may not sell well. I know I have ten ideas for everyone I end up painting.”

Though Jim’s familiarity with whitetails has clearly enabled him to portray them accurately, he admits that such intimate knowledge carries a curse as well. “I know how much is possible with deer, so the potential for feeling like I’ve fallen short is greater,” he laments.

Such intense self-scrutiny is typical of Kasper. The artist’s struggle of translating vision onto canvas is one he encounters daily, and he admits that some of his favorite paintings presented “great struggles” that he ultimately resolved. “Several years ago I did a painting of 17 elk and it presented countless perspective problems that I worked and reworked before I was happy.” Public response to the painting was excellent as well, but after thirteen years of painting wildlife, Kasper is still at a loss to describe the factors that grab a viewer in the gut.

Kasper’s Quiet Time — Ruffed Grouse.

“I’ve had pieces that really took off, and I look at them and ask ‘What did I do there? How did I create that emotional response?’ But there’s no way of telling. It’s so great that you can’t describe or figure out what makes a successful painting. We know all the ingredients that go into one: hue, color, contrast, composition, but you can’t make a formula of those things to create a good painting.”

Don’t look for any formula paintings to appear on Jim Kasper’s easel. His acrylic-on-Masonite originals reveal an artist constantly striving for new and exciting ways to portray Nature’s beauty, though he admits there are some situations that he refuses to paint. “When I look at a vibrant autumn landscape, I think there’s no way you could paint it and make anyone believe what you’ve done — the colors would be too flagrant, and could overwhelm your composition or other efforts. Instead, I prefer to direct the viewer’s attention to other, more subtle but just as precious, things in Nature. I guess it’s the difference between the blast of a shotgun and the song of a bird.”

Jim’s research is an exhaustive combination of photography, sketches and personal observation. While he admits “the camera has made a lot of us [artists] lazy,” each of his paintings is a combination of 50 to 100 slides. “I may use the lighting from one, the color from another. But you simply cannot rely on photographs alone. The distortion created by some lenses can really throw you off if you rely on them too heavily. I’ve found that sketching is a good way to record mental and creative notes while you observe.”

He names Howard Terpning and Robert Bateman as artists who have always inspired him. “Terpning can lay down one brushstroke and just say all kinds of things. I would like to see my own style loosen up like that – get away from some of the tight rendering that you sometimes have to do for the market. And Bateman is one of the greatest. I took a five-day seminar with him in the mid-80s, and that just cemented my ideas about his abilities. He’s one of the best painters and still commercially successful.”

In Fickle Springtime, he contrasted the colorful mating plumage of wood ducks with a somber background of marsh grasses covered in snow, a reminder that spring comes slowly to the North Country.

It seems ironic that Jim Kasper would look at any painter’s life with envy. His own work, critically acclaimed and commercially viable, continues to improve, while on a personal level, his life seems one to long for. At 51, Jim has the look, bearing and energy of a man 15 years younger. But when a shy, smiling little girl pops into the studio, he introduces me to his granddaughter, one of three grandkids he and Elaine watch on weekdays for their daughter Lisa, who lives nearby. The children area fixture at the Kasper household, and Jim views their presence as a rare gift. “I was so busy at work when our own kids were growing up;’ he recalls. “It’s been amazing for me to see the great changes in their personalities and development. I guess I know my grandchildren better than I knew my own kids.”

Jim’s son Christopher lives two hours away but makes frequent drives to the Kasper home outside of Grand Rapids. Jim and Christopher share a love of hunting and fishing, and anyone with these passions would have a tough go picking a better stomping ground than Itasca County. “There are a thousand lakes in our county alone,” Jim says. “Can you imagine? If you fished a different one every day, it would take you several summers to hit them all, and you wouldn’t know a single one of them well.”

The hunting is great, too — for waterfowl on bogs and ponds, lakes and rivers that sprinkle the region. The county’s woodlands support a healthy whitetail population, and grouse numbers are so good that the Ruffed Grouse Society holds its annual “National Hunt” nearby.

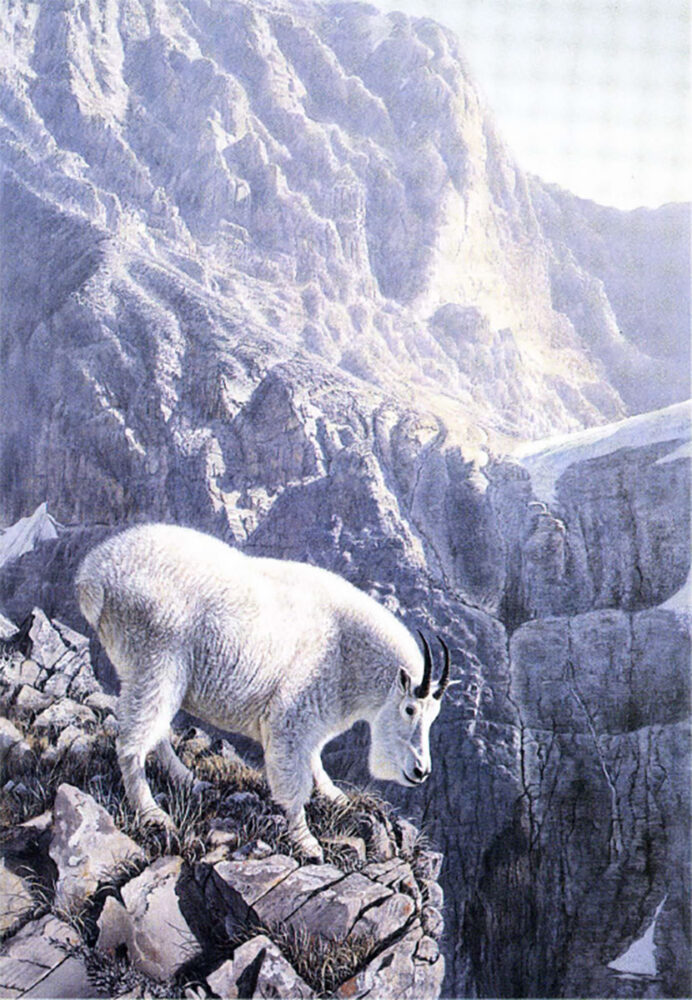

The Minnesota artist and his painting, Daredevil. He set the mountain goat against a sheer rampart to provide the viewer with all unmistakable feeling for the rugged terrain of these magnificent animals.

Jim and Elaine built their woodland retreat over one busy summer two decades ago. Situated on 20 acres near scenic Deer Lake, the house is elegant, blending into its densely forested surroundings, yet maintaining a stately grace. Jim downplays his carpentry skills, saying simply, “I’ve always enjoyed the creative process, and that includes carpentry. Building is really a lot like painting; you don’t do everything at once — it’s one brushstroke or one nail at a time. It is nice to create something that has permanence.”

Last year Jim put on his nailing apron once more and built a studio, a spacious, well-lit addition where he not only paints but displays his work. “We get a lot of calls, especially in the summer, from people wanting to stop out. Adding the studio seemed like something we should do.” Kasper says that like he’d done little more than hung a door, but I’ve worked with enough carpenters to know his work is so good that he could easily have a second career — if he should ever burn out on painting.

But it’s doubtful that Jim Kasper will ever face that problem. He is dedicated to exploring the depth of his own talent as thoroughly as the north woods landscape he loves so dearly. He admits to me he’s always working, at least mentally, even on local fishing trips with Elaine. “She once asked me, ‘Don’t you ever not think and plan around your art?’ But I always do. It’s a consuming thing. But since I enjoy what I do, I can’t imagine a better life.

The artist himself.

“Short of family things, the most awesome, moving experiences I’ve had have been in Nature, and the only way that I can relate those experiences to other people is through my paintings. The great part of being an artist is that I can look forward to changing and improving. I love that challenge. Artists have the capability to get better and better as they age; there aren’t many careers that you can say that for. I look forward to exploring and perfecting those things that I’ve only just started.”

And I, for one, look forward to seeing the fruits of those future journeys.

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now