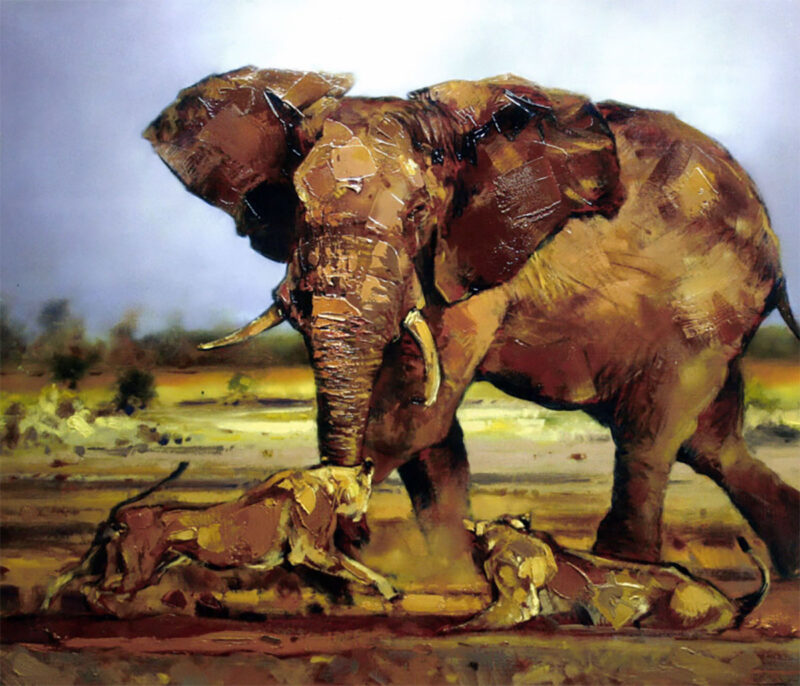

There is nothing meek or ambiguous about a charging elephant, especially when the tusker in question appears to be lunging off a canvas from South African painter James Stroud.

Stroud’s vivid wildlife portraits are so different from the flat surfaces of most sporting art that they could be described as sculptures in paint. A topo map is almost required to navigate through his dense canyons of texture and rivers of color.

And it is no exaggeration to say that Stroud, who made a hugely successful debut in North America at Safari Club International’s 2007 convention, takes an elbow-deep approach to laying down oil.

“I have represented lots of great African artists over the last 20 years, but I have never seen anyone paint like James Stroud, except maybe LeRoy Neiman,” says Ross Parker, owner of Call of Africa Galleries in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. “What James does is blur the edges between classic painting and his own personal expression that is uniquely modern.”

Whether he is pushing paint thickly with a palette knife or using other tools, including his hands, to achieve distinctive visual effects such as portraying dust on a Cape buffalo, the spots on a leopard’s coat or the flowing mane of a lion, Stroud has won praise from collectors for making his subjects actually look — and feel true to life.

“It excites me that someone is able to look at the animal image and be seduced by it, and then be able to look more closely at the paint itself and understand the actual physiology of the illusion,” Stroud says.

When I caught up with Stroud for a face-to-face interview, he was in his adopted city of Cape Town, toting a zebra painting fresh off the easel. The work, an amalgam of sophisticated, abstract brushstrokes and anatomical accuracy, was among several works inspired by a trip into the wilderness of northeastern South Africa, not far from Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

Stroud had heard stories of man-eating lions in the environs around Kruger National Park, and he was interested in studying a protected elephant herd whose individuals are known for their gigantic size. He wanted to eyeball them from the ground. Elephant Confronting Lions is a prime example of Stroud operating at the height of his power. The confrontation is filled with dynamic tension and demonstrates his ability to tell a story with a spare amount of brushstrokes.

In a way, Stroud’s work has generated the same kind of buzz that Neiman did when he emerged during the 1960s and 1970s with his portrayals of athletes engaged in sport, Parker says.

Still, the dilemma for contemporary nature painters, Stroud explains, lies with deciding how to celebrate the environment and iconic African species without falling into the trap of confirming to old visual cliches. “I see my work as an attempt to both affirm the beauty of the natural world and at the same time to dissect the assumptions that we have about what great art is supposed to be.”

Describing his technique as “mushy texture,” Stroud says, “I love to explore the premise of painting in 3-D. I want to make the spirit of the animal appear as if it is coming off the wail.”

In the work, Defensive Lioness, Stroud exhibits one of his stylistic trademarks — a spare, minimalist background that commands the viewer’s attention to the forefront of action. And with the piece Reclining Lion, his acumen in rendering a portrait based on skilled draftsmanship complements his capability as a colorist.

Elephant Confronting Lions

James Stroud’s worldview is a reflection of experiences that were imprinted upon him as a child in the bush. A South African native born in 1970, he grew up on a timber plantation in eastern Mpumalanga on the edge of Kruger Park. “I came to identity with our farm as its own little natural kingdom,” he says. “You didn’t have to venture out to experience what some people call wildness. Wildness came to you.”

On a primal level, he had a front row seat to predators and prey. Mpumalanga was a crossroads for international hunters and photographers. Sketching both people and animals, Stroud went to a rural school where Afrikaans was the first language and English second.

After receiving a fine art degree from the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg and receiving tutelage from Jenny Heath, daughter of the late artist Jack Heath, he set out for Europe and studied the Old Masters, focusing on the Romantics and Impressionists before delving deeper into the works of Abstract Expressionists. Among his eclectic influences are Vincent van Gogh, Edouard Manet, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Ray Harris Ching. At the university, Stroud also pursued ceramic media, which has helped him to make his art more sculptural.

“When I start applying the paint, I remember the smell of the landscape —the plants, the dust, and the scents of animals that hung in the air,” he says. “Painting for me doesn’t start with merely a visual image. It’s always about a feeling of being there in the field with your subjects that you don’t get when you are attempting to lift information off a photograph.”

Stroud’s boyhood home in Mpumalanga, part of the historic homeland of the Eastern Sotho tribe, was very much colonial in character during his youth. The end of Apartheid in 1994 brought a dramatic close to racial separatism. On the positive side, it has come replete with an eruption of young musts of all skin colors who are creating a new national artistic identity. “There are people who use art freely to uphold the status quo and others who challenge it,” Stroud says.

Since the late 1990s, Stroud has been identified as one of the most promising emerging wildlife painters in the new South Africa. “At heart, I paint representationally, which is to say I want my subjects to be recognizable, but I love to explore the abstract shapes and colors that light and shadow create,” he says. “I have no interest in rendering a literal copy of an animal, landscape or still life. All art, fundamentally, is abstract. I want to draw out the elements that give a subject its personality.”

Although the post-Apartheid era has brought hope for young people, there is also fear, not only for human safety but the survival of wildlife that is imbedded in the psyche of all South Africans. “As an African, you quickly learn that you mustn’t dwell on trying to achieve any sense of permanence because things can change and they change quickly,” he says.

Like LeRoy Neiman, Stroud’s interpretations have been praised for their originality and stylization, though he prefers natural color as a counterpoint to the garish palette favored by Neiman.

“Any hunter tries to recount the drama and excitement of the hunt in ways that photos and other images of dead game animals won’t do,” he says. “They want the essence of the animal. I try to give them that.”

As part of his collaboration with Parker, some of the proceeds from the sale of his paintings have gone to support habitat protection and anti-poaching efforts in Africa. “Hunting money is vitally important to conservation in Africa,” Stroud says. “It has been inseparable and I don’t see it going away.”

Despite the cultural turbulence, Stroud says he can’t imagine leaving South Africa for safer ground. “It is my home,” he says.

Some of the greatest artistic masterpieces in history, after all, were born during times of social unrest. For James Stroud, the survival of wildlife serves as a reflecting pool for the fate of an entire continent. “To be honest, it feels good to be here in Africa now,” he says. “It remains an extremely interesting period to be a witness to all that’s going on. No one knows where the path to the future is leading.

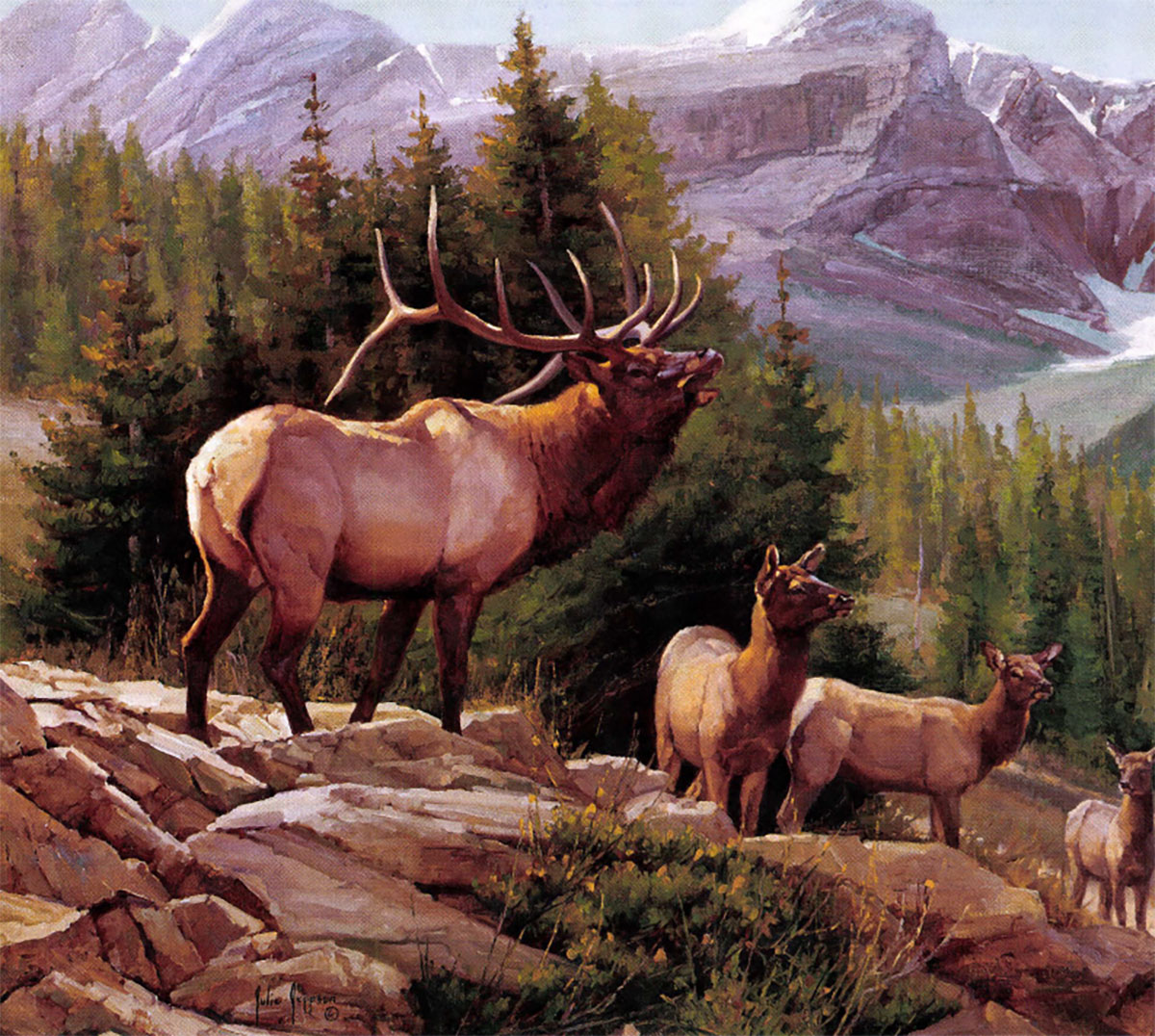

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now