Cutting out the friendly chatter on a grouse hunt helps bag more birds, but what about hunter camaraderie?

Elmer Fudd’s advice of being “vewy, vewy, quiet” didn’t work out so good for him when hunting “wabbits,” but, as it turns out, it does on “wuffed” grouse.

Here’s how it went down: two hunts, same weather conditions, same habitat, same setup, same time of day. Both hunts were in the third week of October, prime grouse time.

On the first hunt, a buddy and I and our two experienced grouse dogs, a black Lab and a springer spaniel, hunted on and around my land in Carlton County, Minnesota. The area we hunted was a mile of two track extending along and south of my property through a mix young and old aspen/maple/balsam habitat and tag alder wetland.

On the first morning hunt, the dogs put up four or five grouse off the trail far enough into the forest that we didn’t get a good look at the birds, missed a few shots, and bagging nothing. As usual, we were talking along the way, walking at a good clip, calling out birds, bells on the dogs, whistles blowing, and generally carrying on in our normal fun manner.

The next weekend I went up by myself. On the two-hour drive I started thinking about the weekend before, and it dawned on me that the racket we were making was driving the birds into the woods far enough that we weren’t getting good shots once the dogs flushed them. I’ve probably had this epiphany before, but last year I had it again.

So, this time I took the bell off the dog, put the whistle in my pocket, used the e-collar tone button to work the dog, walked slowly, and generally got my stealthy predator on. The results: The dog put up four coveys of four to five birds each. I bagged three grouse and a woodcock.

True, the author has bagged more birds when hunting alone and not talking, but where’s the fun in that?

Yes, grouse are wary, and they will run and run quite fast, but the difference between a five-yard shot and a 10-yard shot in thick aspen or tag alder is often the difference between bagging a bird or not. I don’t care how fast or good a shot you are, No. 7 shot won’t go through a decent-sized tree and kill a bird.

Sure, it’s not unusual to hunt the same area one day and flush few birds and hunt the same spot the next day and have a good hunt. There are many factors at play on any given hunt, but I believe hunting alone, slowly and quietly, made the difference.

Pheasants, which I’ve hunted extensively, are well known for hoofing it at the first sign of approaching hunters and dogs, especially late season. But grouse? I didn’t think so, and I was wrong.

Another factor in grouse hunting is hearing the flush as a cue that a bird is on the wing, especially in heavy cover. But I wear ear plugs, and not using a dog bell makes it hard to hear a bird. However, I found by hunting quiet birds flush closer and are easier to hear. This makes a big difference.

Grouse hunting buddy Jared Wiklund, a lifelong Minnesota grouse hunter, offered some additional insight.

“Although being quiet in the grouse woods can and does produce more birds for any seasoned hunter, another factor to consider is the age of your quarry. I’ve seen time and time again where young grouse broods will only flush once a hunter has closed the distance, regardless of the noise being made. Camaraderie during the hunt speaks for itself, and I personally don’t mind having limited conversations with good friends in the autumn woods if it means busting a bird or two more.”

Indeed, those young, early season birds can be easy pickin’s, but those second-year-class birds can and will run pretty fast when alarmed. Another thing: Even winged birds can run very fast, so a close-in shot on open ground helps with the retrieve.

Of course, a pointing dog also helps with running birds, but many a grouse won’t hold still for a pointing dog and will run and flush out of range anyway. I know; I once ran Brits on grouse.

True, I can usually put more birds in the bag using the silent approach, but I don’t want to give up b.s.-ing with my grouse friends. It’s just too much fun. But, on those days when it’s just me and Hunter, the quiet approach will suit me fine.

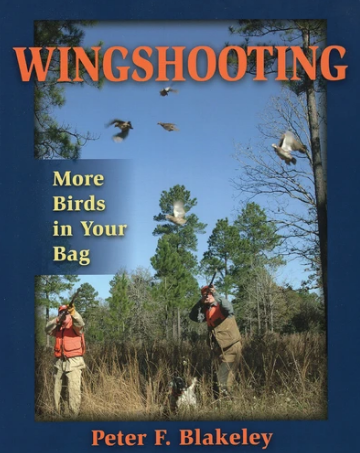

Successful shotgunning depends on creating accurate sight pictures of the birds. Wingshooting explores the three variables that determine each sight picture—the flight line of the bird, its speed, and the distance to the bird—to help you decipher the correct lead for each bird.

Successful shotgunning depends on creating accurate sight pictures of the birds. Wingshooting explores the three variables that determine each sight picture—the flight line of the bird, its speed, and the distance to the bird—to help you decipher the correct lead for each bird.

Peter Blakeley’s approach emphasizes how to apply a specific lead to a specific target, and his colorful stories bring the hunt to life in these pages. Includes chapters on bobs and blues; doves; pheasants, grouse, and partridge; ducks and geese; and woodcock and ruffed grouse. Shop Now