“If you have men who will only come if they know there is a good road, I don’t want them. I want men who will come if there is no road at all.”

David Livingston would have welcomed help; but he knew the perils of travel in virgin Africa. She ate the weak.

Livingston, A Scot, was born March 19, 1813, in Blantyre, Lanarkshire. His education and a zeal for the Bible nudged him into missionary service among tribes below the Sahara. Committed, but smart enough to modify his message and habits to suit the wilderness, he traveled without military escort and forged friendships with people distrustful of armies and tactless explorers. In 1866 Livingston set off to find the source of the Nile. When nothing was heard from him for three years, the civilized West mounted an expedition to find him.

At its head was a most unlikely man.

John Rowlands, born out of wedlock January 28, 1841, was given his father’s name. As a youth, he left his native Denbigh in Denbighshire, Wales, to go to sea. He jumped ship from a merchant vessel in New Orleans, then, to start a new life, took the name of wealthy cotton broker Henry Stanley.

The enterprising lad found work in newspapers. He traveled with the British Expeditionary Force to troubles in Ethiopia and reported on the Spanish Revolution. Then the New York Herald commissioned him to find Livingston.

Stanley landed in Zanzibar January 6, 1871. He lost no time mining locals for information. The trail of tips led him, late that year, to Ujiji, a settlement on Lake Tanganyika. “Dr. Livingston I presume.” Stanley didn’t waste words. The ailing missionary replied with equal understatement: “Yes, and thankful I am here to welcome you.”

Stanley returned to the relative comforts of the U.S. and England. He passed in London May 10, 1904. Livingston had just a year and a half to live. He insisted on spending it on the continent he loved, with people who returned that affection. Dysentery claimed him May 1, 1873, in what is now Zambia.

Early to the Upper Nile, Livingston had come to Africa nearly 350 years after Vasco de Gama. In 1498 the mariner hanged his Arab pilot when he discovered a mutinous plan to smash the ship on a reef fronting Mombasa’s harbor. That narrow channel would become a thoroughfare at the height of the slave trade. Mombasa—the island and city—endured Portuguese rule from 1505 until Arabs seized control in 1729. Governance fell to the British East Africa Association in an 1887 pact with the Sultan of Zanzibar. Within a year the Association was the Imperial British East Africa Company. The British Foreign Office assumed Company assets in 1895. A rail project followed Colonial Office authority into Uganda.

John Henry Patterson arrived in Mombasa March 1, 1898. A week later he’d gathered supplies needed at rail-head near the Tsavo River. A train took him across the Salisbury Bridge over the Strait of Macupa and chugged up through the forested Rabai Hills. Past the Taru Desert, after a pause at Voi, the landscape greened up. The N’dungu Escarpment appeared at dusk, shortly thereafter, the river. Rails laid by thousands of Indian coolies gleamed beyond. An engineer, Patterson was to build a permanent bridge over the Tsavo and finish the project 30 miles to either side. He couldn’t have imagined work would be stalled and his life both threatened and defined by two man-eating lions!

A decade later, killing lions was just the sort of work John Alexander Hunter was looking for.

Like Livingston, Hunter hailed from Scotland. Born May 30, 1887, near Shearington, Dumfriesshire, he followed by seven years the birth of Walter Dalrymple Maitland Bell near Edinburgh. Both were restless lads, chafing under rules and with little patience for school. Bell, who had lost his parents by age six, fed an early lust for adventure by reading Ronaleyn Gordon-Cumming of Altyre, who left a military posting in India for Africa. When a very young Bell ran away “to shoot buffalo in America,” a Glasgow policeman sent him home, where he languished until old enough to work at sea. Voyages to Australia and New Zealand brought him around Cape Horn. He turned 14 on his return to Scotland, Africa on his mind.

Hunter’s father was a prosperous farmer, with 300 acres of cropland, 3,000 in pasture. An ardent sportsman, he often prowled, “the marshes that surround the Solway Firth with a fowling piece over his arm.” Young John—J.A., as he’d come to be known—tramped Lochar Moss, a vast bog rich in wildfowl. By age eight he was afield with his father’s Purdey. Soon he was poaching, “a fine business requiring the greatest of skill.” Arresting poachers years later, he allowed that in his youth, “dodging keepers [prepared me to] stalk big game…. I got as much of a thrill bagging a rabbit behind the keeper’s back as [shooting an] elephant with 200 pounds of ivory.”

A difficult pupil and reluctant Protestant, J.A. cared little for farming. But it was love, at age 18, that would release him from Shearington. The woman was older. The local minister, apprised of the lad’s other amours was unyielding in condemnation. Distraught, J.A.’s parents suggested he visit a relative in Kenya.

Africa! He embarked with the Purdey and a .275 Mauser that had barely survived the Boer War. But J.A. found his cousin a drunken brute, his plantation a wreck. Weeks after his arrival in 1908, he made ready to slink back home. Then, at the local Bank of India, he chanced upon another Scot—who would have none of his retreat. “I have a friend on the railroad….”

John A. Hunter arrived in Kenya in 1908 with a Mauser much like this 7.65, but in 275 Rigby (7×57).

Shortly Hunter was riding the Mombasa-Nairobi rails as a guard, the old Mauser in the chop box. “Whenever we passed a [lion or a leopard] I would lean out the train window and bag him. Then I’d pull the Westinghouse release to stop the train, jump out with the native boys and skin the beast. People were in no great hurry in those days …. The engineer [would signal] me with the whistle …. Three toots meant a leopard, [two] a lion.”

One day a series of toots brought Hunter to the railing, where he saw his first elephants. Grabbing his .275, he leaped off the train. “Wait!” said the engineer, “I wanted you to see them, not shoot one!” But J.A. wouldn’t be deterred: “We’ll knock them over like rabbits!” The rifle’s report triggered a stampede. Elephants thundered by on both sides. As dust settled, Hunter “found the engineer on his knees praying.” The bull was gone. On a return trip the next day, however, they spied its carcass. The tusks brought J.A. £37, “more than I made in two months as a guard.”

In that day ivory hunters were a dashing lot, though some, like Bill Judd, died under the beasts. “I met Karamojo Bell,” wrote J.A. in his book Hunter, published in 1952. Lion hunters had his attention too—men such as Leslie Simpson, reputed to be the greatest of his day and to have shot 365 lions one year. Allan Black’s hat bore tail tips from 14 man-eaters. Fritz Schindelar, an ex-officer in Hungary’s Royal Hussars, dressed in white riding breeches to course lions horseback, perilous sport that ended when he was dragged from the saddle and killed. “These men were my heroes,” Hunter recalled, “I longed to be like them.”

Hunter brought Africa to my boyhood bedside 60-odd years ago: “Two natives were returning to their village one evening when they saw a great black mass in the shadows of their huts.” Shouts to scare it off instead brought it on. They ran for their lives in different directions. One man had a red blanket. The elephant followed him. Villagers, helpless in their huts, heard the man’s screams as the elephant caught him, put a foot on him “and pulled him to pieces.”

J.A. was guiding two Canadian hunters for bongo in the Aberdare Forest when a runner brought news of the killing. Graciously they released him to hunt the elephant. He left immediately with Saseeta, his tracker. They found the body at the end of a zigzag trail. Hunter had felt the man’s panic. “It is like running in nightmare, for the wait-a-bit thorns hold you back and the creepers pull at your legs, while the elephant goes crashing after you like a terrier after a rat.”

That night, the elephant destroyed a native shamba five miles away. After a 9,000-foot ascent at dawn, Saseeta spoored the bull deep into the Aberdare, where thick bamboo and tall forest nettle slowed their pursuit. Briars forced them to crawl. Then a branch cracked, mere feet away. J.A.’s Jeffery double, a 475 No. 2, felt small. “[My heart] sounded like a drum.”

A twist of breeze ended the drama. The bull vanished.

In fading light, the hunters pressed ahead. Again they heard the animal, now downwind trying to catch their scent. Straining to see, J.A. made out a hulk, but indistinct in the gloom. “I could not tell head from tail.” Another spin of the air, and the beast was gone. Their only option now: toil back to the village.

Just after dawn a half-naked runner arrived to say the bull had raided another garden three miles off. Local guides led through the steeps to the spoor, where it entered tangled mats of bamboo under ranks of toppled trees. “Moving quietly was impossible.”

A noise ahead brought J.A.’s rifle to cheek. “Instead of the elephant, a magnificent male bongo [stepped out]—the very trophy [my clients] had been after for many long weeks!” After a pause to let him drift off, the men proceeded. Then, the sound of rending bamboo. The elephant’s trunk moved above the stalks. At 15 yards Hunter could see the body, but a lattice of bamboo screened its vitals.

Suddenly the bull saw his pursuer. This time he did not run. “Almost before I could raise my rifle he was on top of us. His great ears were folded back close to his head,” and his trunk was tight to brisket. “I aimed the right barrel for the center of his skull … 3 inches higher than [a line] from eye to eye…. For an instant after the shot the bull [hung] above me. Then he came down with a crash.”

After sips of water from bamboo sections pressed upon him by grateful guides, Hunter examined the ivory—“very poor” at 40 pounds per tusk. A hole at the base of one delivered up an old musket ball. It had embedded in the nerve. That painful wound, he concluded, was why this bull had “become a rogue.”

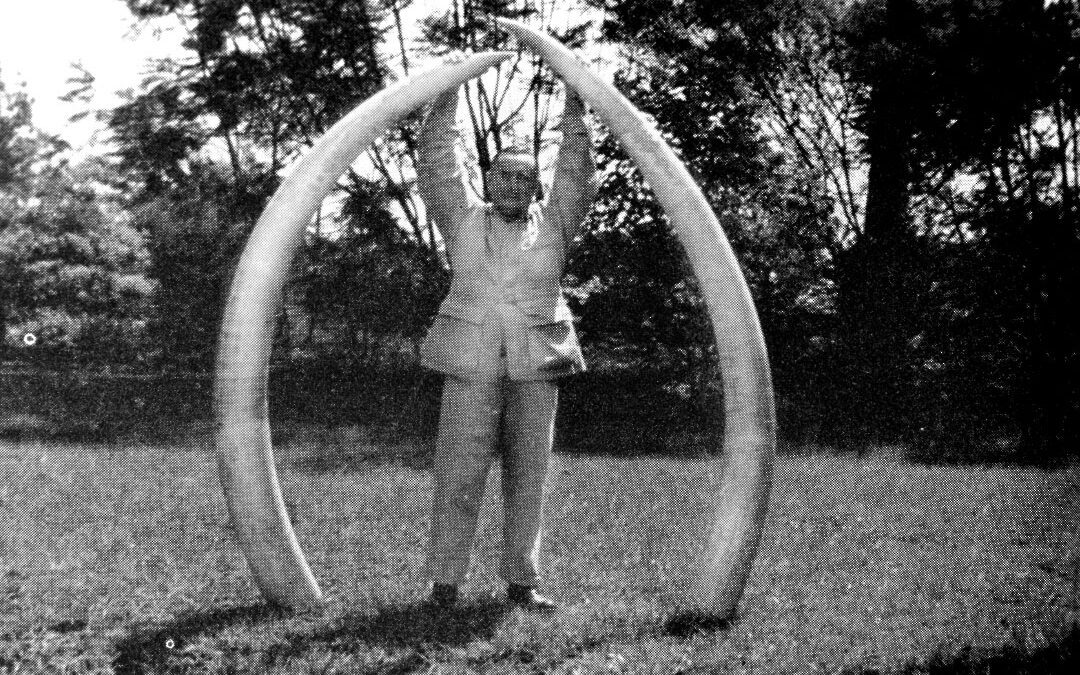

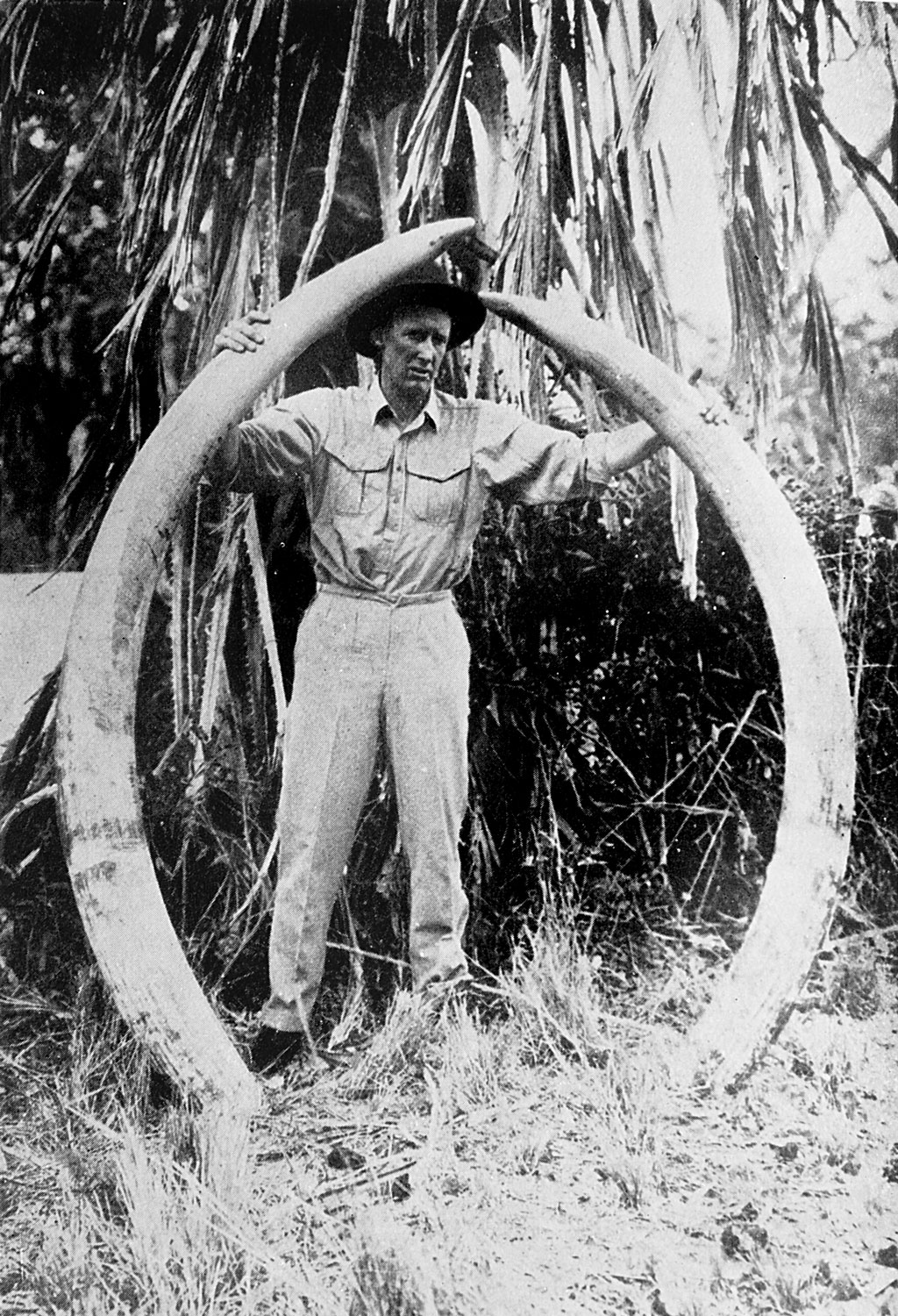

J.A. Hunter would kill more than 1,400 elephants during his years afield. Early on, he shot most for their ivory. “At that time [it brought] 24 shillings a pound [and good tusks might average 150 pounds a pair]. An experienced hunter could drop an elephant with nearly every shot, and a 450 No. 2 cartridge cost only one and sixpence.”

Whatever the mission, J.A. got close to his target. He favored a brain shot, but at very short range the difference in height between man and elephant “makes this shot difficult.…” Once, as he stalked two bulls, “a third [popped up] less than 5 yards [away]. He seemed to have risen out of the ground…. I fired about a foot below [the level of his eyes], the missile passing through the trunk [into] the brain.”

Close calls with dangerous game are the stuff of safari legend. But threats come from unexpected quarters, too. A few months into killing lions and coming up whole, Hunter had confidence in his shooting and instincts. His nerves had proved steady in tense moments—as when he’d tossed a rock to flush a lion. The second cat was a surprise. Both came straight at him. Firing as if with a shotgun, he dropped the first as the other “gave a great leap and passed right over my head, knocking my hat off….”

Sure of his bushcraft, too, he grabbed his Mauser and a knife one day to hunt a 7-mile patch from Tsavo station to Kyulu Hill. A half-day’s trek. He was startled, after a time, to come upon footprints. They were his. He had no compass, no water. “I felt panic for the first time in my life. I suddenly realized how much I depended on my native boy, for natives seem to have a compass inside their heads….”

Climbing thorn-studded trees to see the sun proved impossible. Back-tracking would take hours. He pressed on into the night, water now ever on his mind. The next morning he again met his own trail. Exhausted, he no longer skirted animals in his path. “If [a rhino] charged, I shot him, for I was too weak to run or dodge.” Another night brought delirium. “I would have died [the next] day if I had not stumbled upon a rhino watering hole, a foul mass of ooze…. I fell into it and drank until I could drink no more.”

He survived another night but was near collapse the following day when a glint in the bush drew his eye. He staggered toward it and “fell sobbing to my knees” at the base of a telegraph pole, whose wire joined Tsavo Station and Kyulu. “I was saved.”

Humbled and wiser, Hunter recovered his health in Nairobi. There, he met Hilda Banbury, whose father owned a music shop. Courtship and a wedding followed, with J.A.’s promise to find less stressful work. Nairobi was growing fast in 1918. A transport company would grow, too. He bought mules, horses and wagons, then began hauling freight in town and for surrounding farms. He was soon bankrupt.

“You aren’t a businessman,” Hilda agreed. “Now that’s out of your system, you can be a hunter.”

Leslie Simpson sent him his first clients; Americans keen for a trip into the Serengeti’s game-rich but largely unexplored Ngorongoro Crater. To guide him, Hunter found an old Dutch ivory hunter who’d lost his thigh muscles to a rhino. Everything needed for the three-month safari would be born on the heads of 150 Wa-Arusha porters. Scolded for tardiness the first day, they fell to chewing grass in their fury and threatening staff with knives. The cook was more docile, if not fully vetted. Caught one day smearing his body with grease from a roast, he guiltily began wiping it from his belly back onto the meat.

That safari brought more clients. Soon Hunter was employed by Safariland, Inc., one of several Nairobi outfitting firms. Hosting required skills that had little to do with hunting.

Among his most fetching clients was a baroness whose husband “was insanely jealous of her.” He hired an ex-officer in the German Army to keep an eye on her. Keen to hunt, the baroness was unable to shake her heavy-footed escort. But one day she and Hunter convinced the major the cover was too thick for three people. He stayed back. Posting her on the rim of a donga, J.A. entered it to flush a big warthog. Suddenly she screamed. Fearing the worst, he tore through the bush—and came upon her all but naked! “For an instant I thought she was mad. Then I saw [the] safari ants. These are terrible things, half an inch long, with jaws like pincers….” He spent several minutes pulling ants, then scraping her with the back of his knife to dislodge remaining heads. Just as she got her clothes back on, the major burst in upon them.

An insatiable demand among native tribes for more arable land brought Hunter contracts to shoot game competing for that space. In the mid-1940s, Kenya’s government engaged him to rid a section of the Machakos District of black rhinos—for agriculture and for tsetse fly control to open the area for grazing.

One day he and his scout spied a pair of rhinos ahead, a third to the left. As he closed for a shot, the pair swung toward him. He fired at the cow. She slumped to her knees as he reloaded. The bull came. “A bullet from my right barrel hit him above the brisket. He never flinched….” A solid from the second barrel struck below the ear. Hunter had just shut the breech on two fresh cartridges when the third rhino crashed into the open—the scout hanging desperately to its horn! Hunter sidestepped the charge, unable to make a killing shot without hitting the boy. “I waited a [split] second, then fired for the rhino’s shoulder.” The bull fell; the boy catapulted forward “like a rider whose horse has refused at a jump.” He landed hard and lay still. Hunter was paralyzed, thinking he’d killed them both. Then his scout moved. “No sight had ever given me greater joy.” Racing to help him, he found no bullet hole, no serious injury. “The boy had been able to grab the foremost horn and hold himself clear” on that wild dash.

From late August 1944 to late October 1946, Hunter killed 996 rhinos in the Makueni area of the Machakos District. Retracing his steps after three months that yielded 163 to his rifle, he was stunned by changes wrought by clearing crews. Tall thorn had given way to bare red dirt. Pale snakes of packed earth marked old rhino trails. Wakamba huts shared the plain with bleaching bones. “It seemed only yesterday that we had crawled along these [paths] on our hands and knees….” Rhinos, he lamented, would soon be only legend here. Despite his role in killing off “these strange and marvelous animals,” he questioned the wisdom of such slaughter “to clear a few more acres for a people… ever on the increase.”

After the Makueni rhino hunt, Hunter moved from the family’s Ngong Road home near Nairobi to Makindu, a stop on the Nairobi-Mombasa Railway. He’d been appointed game ranger there, a position he would hold into the 1950s. The Hunters’ two girls had married and moved away. The second son was an architect. The eldest, “living in the [world’s] finest hunting country,” had returned to his Scottish roots in agriculture. “Well,” wrote his father, “every tub must stand on its own bottom.” Hilda divided her time between Makindu and a house in Nairobi until their two youngest sons finished school.

J.A. and his scouts patrolled a vast game reserve. Spotting a bush camp one day, they surprised Wakamba poachers, who grabbed their bows. “This man isn’t a ranger, but an ivory poacher!” shouted a scout. “His quick thinking may have saved my life,” wrote Hunter. Even a scratch from an arrow with mrichu poison can kill. Natives found these trees by looking for dead hummingbirds drawn by its purple flowers. The bark, boiled into a tarlike goop and mixed with other natural toxins like snake venom, was smeared on the stems of arrowheads inserted into shafts made from hollow reeds. According to Hunter, a Wakamba bow drew about 75 pounds. It could shoot an arrow through a Masai buffalo-hide shield tough enough to stop musket balls “and kill the man behind it.”

Explaining conservation to native hunters who had killed as need demanded and chance allowed, took tact and understanding. Turning a blind eye to subsistence hunting during difficult times, Hunter made every effort to protect elephants and rhinos, pursuing merchants funding poaching rings and even planting a scout to gather evidence when a sport hunter repeatedly shot rhinos he claimed were charging.

J.A. Hunter had his pick of rifles for big game.

Hunter grew up in blackpowder days, when Africa’s big game fell to rifles such as this 577 BP Express.

He “relied mainly on a 500 [double] hammerless ejector … with 24-inch barrels.” That 10 1/4-pound arm was by Holland & Holland, to his notion “the best in rifle makers.” Recoil of the 577 and 600 Nitro Express put him off those cartridges; but he thought it unwise “to hunt elephant, buffalo or rhino with a gun of less than 450 caliber.”

In southern Tanganyika he once met a sportsman named Lediboor who had used his 405 in India and was confident it would take an African elephant. J.A. tried but failed to steer him to a more powerful round. The man was later killed by an elephant that dropped to his shot but was only stunned. Lediboor’s remains indicated he had not suffered.

Opinions as to the most dangerous of Africa’s “big five” were once pitched by men who’d killed hundreds of them over long careers. Such experience is hard to find now. J.A.’s time in the bush, and his tallies of elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion and leopard give his ranking—the reverse of this list—credibility.

The fraternity of professional hunters in East Africa was tight if informal early on. Distances and transport of that day precluded frequent get-togethers, but help and a welcome were ever at hand. One of Hunter’s friends was Denys Finch-Hatton, a Brit who shared J.A.’s birth year. Escaping upper-middle-class boredom in London, Denys sailed to Cape Town in December 1910. Short months later, he arrived in Mombasa and took the “Lunatic Line” (Uganda railroad) as far as Nairobi. A pilot as well as a hunter, Denys was also known for his dalliances with Karen Blixen, wife of professional hunter Bror Blixen. She would author Out of Africa under the pen name Isak Dinesen.

Denys Finch Hatton.

Denys and J.A. worked together to get motion-picture footage of charging buffalo. In 1930 they drove a Chevrolet into Masailand. When a rock tore the engine pan, Denys patched it. They motored on trails to the Mara River. “Every slope as far as the eye could see,” wrote Hunter, “swarmed with game.” Later he’d add: “Denys opened up the Masai with me. He was fearless and fair, an undaunted hunter….”

On May 14, 1931, J.A. and Denys, with a handful of others, were evening guests of Vernon Cole, District Commissioner at Voi, a community so small aviatrix Beryl Markham called it “hardly more than a word under a tin roof.” Denys had flown there in his Gypsy Moth to try scouting for elephants by air. About to start a safari, J.A. may have already left the next morning when Denys’ passenger Hamisi pulled the chocks. The Moth sputtered to life. It chattered faithfully down the strip, lifted the men into blue skies and gained altitude in wide circles. The Coles were watching when suddenly the engine coughed and the yellow Moth plummeted, crashing behind trees a mile away. It burst into flames on contact.

J.A. Hunter mourned the death of his friend. Still, he was accustomed to loss. “When I first came to Kenya…game covered the plains…. I have seen jungle turn into farmland and cannibal tribes become factory workers.” He admitted his ivory hunting and animal control work for the government contributed to these changes. Still, he insisted, he had “a deep affection for the animals I had to kill….

“I am one of the last of the old-time hunters. The events I saw can never be re-lived. No one will ever see again the great elephant herds led by old bulls carrying 150 pounds of ivory in each tusk [or] hear the yodeling war cries of the Masai [spearmen] after cattle-killing lions. Few indeed will [say] they have broken into country never before seen by a white man. No, the old Africa has passed….”

A few years ago, I climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, through its diminishing snowfields, up, up into its highest rock, and looked over plains from which J.A. had gazed at the hoary 19,340-foot summit. That night, in the thin, cold air under impossibly crisp, bright stars, time fell away. This mountain had pierced Africa’s sky before Hunter, before Livingston. Before de Gama. Vast bush below, now scratched faintly by roads long walks apart, would color at dawn as it had for oceans of game a century gone—as it had for men willing to come when there were no roads at all.

No Better Book?

Published with the assistance of Daniel Mannix, Hunter is neither a primitive diary nor self-serving autobiography. It ably distills the evolution of African hunting during the 20th century’s first half. J.A.’s adventures lose nothing in the telling, but they’re rich in detail—and anchored by people and events that bring context. I first read Hunter when gasoline sold for 22 cents and Ford’s Mustang was a concept. It’s one of few books on my shelf that begs repeated use.

John A. Hunter’s first book, White Hunter, was published in 1938 while he was still active afield. Original copies are scarce. Safari Press offered a limited run of 1,000 in 1986.

Tales of the African Frontier, published with Daniel Mannix in 1954, was re-published by Safari Press in 1999. It took shape before Hunter saw print. Interviewing J.A., Mannix was impressed not only with his life, but with those of other pioneers who had opened East Africa. Hunter had known many. The rest in Tales came to life in documents and more interviews. The book sifts fact from fiction—as much as is possible, given memory gaps and the inevitable intrusion of legend. And the facts are most colorful!

Hunter’s Tracks, published in 1957 with an assist from Alan Wykes, is the story of a man-hunt to dissolve a poaching ring and bring a clever criminal to justice. J.A. is here the game ranger. Frequent, but well-crafted, hops from reminiscence to the urgent present bracket natural history, hunting anecdotes and the profiles of compelling characters. It’s better than fiction!

This article originally appeared in the 2024 Adventures issue of Sporting Classics Magazine.