But every now and then, his wife will get a certain look in her eye and announce it’s time to repaint the interior in Chip and Joanna’s latest signature color, and that all the trophies must come down. Don’t fight it. Either schedule a hunt in some country with a name your wife can’t pronounce or take advantage of the chaos to relive the old memories each of those trophies holds.

I always write notes on the backs of my mounts: where, when, friends and notable fellow hunters, guide (if any), as well as any memorable occurrences that made the hunt unique. So, when I recently had to manhandle more mounts than I even realized I had, a lot of memories came rushing back.

A hunt in southern Utah with my old friend and partner in crime (and Emmy award-winner) Gerald McRaney, where he invited his real-life brother to join him. There were other hunting friends in our do-it-yourself camp, as well as a non-hunter—a fitness buff who looked like a better-looking, more muscular version of me, who just wanted to camp out with us and who volunteered to run the camp and do all the cooking.

It was unseasonably warm that year, and the deer were spread out all over the place, mostly under trees at higher elevations and in the shade of north-facing escarpments, so we all had to do a lot of pre-dawn hiking to get into good country.

Mack and his brother hadn’t seen each other in a long time, so they did a lot of catching up as they hiked that first morning. In fact, they did so much catching up, they forgot to note where they were going and got themselves hopelessly lost. Eventually, late that night, they spotted a campfire in the distance and stumbled into the camp of the local sheriff and his party. Fortunately, the sheriff was able to recognize where our camp was from Mack’s description of it, and was kind enough to drive them back.

Meanwhile, in our camp, the fitness buff had gotten restless and decided to go for a jog. Because none of us had taken the unexpected heat wave into account, he hadn’t packed any appropriate clothing, but no worries: we were camped back of the beyond, miles from anywhere, so he just put on his jogging shoes, stripped down to his briefs (bright red, for safety), and took off on an old logging road. Of course, that was when a party of local hunters drove by, gazing with fascination at this apparition.

So later, the local paper reported that Jameson Parker had gotten lost and had to be rescued while hunting in his underwear. I have never hunted in that part of Utah since.

A Roosevelt elk hunt on huge (84-square-miles) Santa Rosa Island, many years before the federal government decided to return the island to its pre-European condition and exterminated some of the finest elk and mule deer populations anywhere and running a fine and responsible ranching family out of business.

Something went wrong, I forget what now, but my guide and I had to split up, though we agreed to meet on the windward side of a small mountain. My guide was the legendary outfitter and land manager Wayne Long, and he suggested I hunt my way over the mountain in a certain direction. I pointed to another area where there was a likely looking draw with some trees in it. Wayne told me that the bulls were still running together at that time of the year and there wasn’t enough feed or cover in that draw, but if I wanted to hunt there, so be it.

He took off to do whatever needed to be done and I hunted my way slowly up to the draw. I got there just in time to see the largest elk I had ever seen, Roosevelt or Rocky Mountain or Tule, bed down about 200 yards away, proving that not even the finest and most knowledgeable outfitters can always predict the ways of wildlife. I sank, by inches, down into the grass, eased a round into the chamber, shouldered the rifle, and . . .

This was a long time ago and optics weren’t as good in those days. Between the angle of the sun and its reflection off the bright blue Pacific, all I could see was glare. If I lowered the rifle, I could see the bull as clearly as I could the sea and the trees, but through the scope or my binoculars, I might as well have been hunting by Braille.

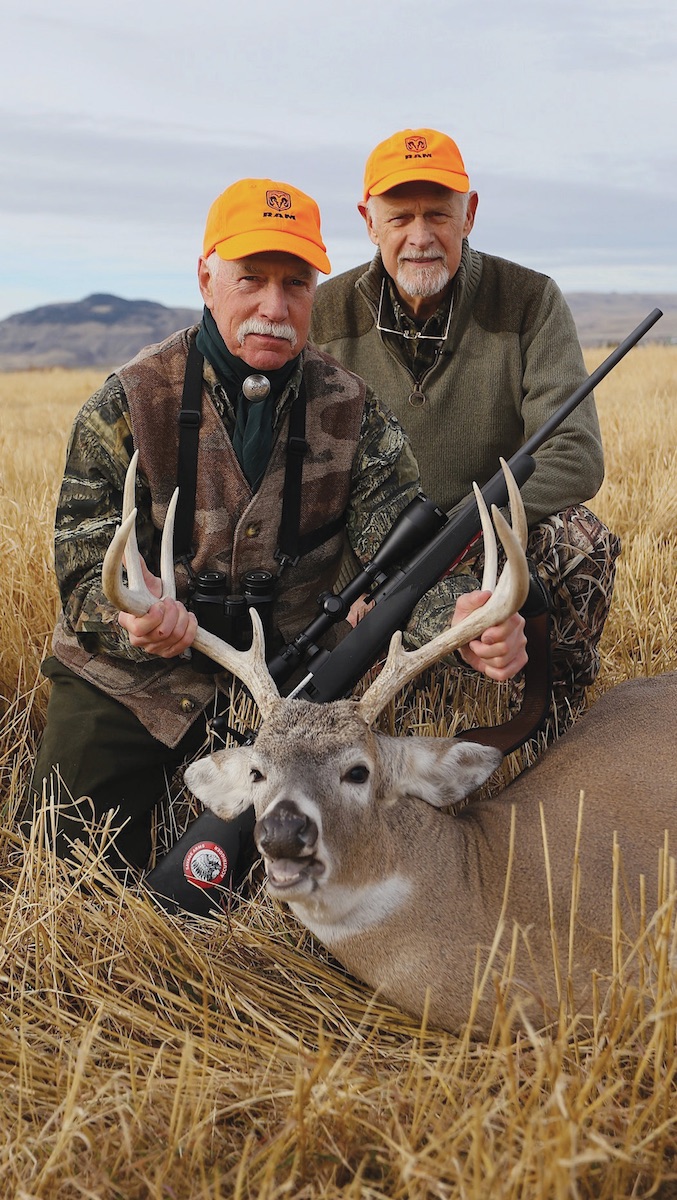

The author (right) and his old friend Gerald McRaney examine a good whitetail Gerald killed while hunting with Montana Bucks and Ducks in the southwestern part of the state.

Time passed. A lot of time. You know that tautology, “slow torture?” That’s how it felt. The predator watching his prey is necessarily keyed-up, and remaining in a keyed-up state for long periods of time is not easy or enjoyable, but that damned bull showed no signs of ever moving, and the sun seemed to have stopped for a prolonged coffee break.

Finally—an hour later, two hours later, more?—as the light began to change just enough for me to see things, sort of, through the scope, the bull stood up and turned slightly, and I was able to place a round right behind his front shoulder. Fortunately, the shot was good, and Wayne, who had been watching the whole affair from somewhere up behind me, came running down to pump my hand.

We went over to admire my elk (I have never submitted anything for trophy status, but according to Wayne, he would have qualified for both SCI and Boone and Crocket) and then we rolled him over. That was when we discovered he had no ivories.

Ivories are sometimes called “buglers” because people erroneously thought they were used for that purpose. In fact, according to wildlife biologists, they are the remnants of prehistoric tusks, and made of the same material you would find on elephants and wild boar.

In very old elk, the ivories are sometimes worn down to next to nothing, but that was not the case with my elk: he was big, well-muscled and in his prime, but minus ivories. What this had to do with his being a solitary, misanthropic bull at a time when he should have been hanging with his buddies, I can’t answer. But I can still see him lying in his bed, quartered away from me, and as safe in the slanting light as if I had been hunting with a slingshot.

A Colorado hunt not far from the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, where I made one of the two best stalks I have ever made. I glassed a superb mule deer buck—both wide and heavy—resting with some does in a small grove of scrub and cedars. It was a warm and sunny day, but with a strong west wind. I dropped down from my vantage point and made a big circle so I would be directly downwind of the buck. Well before I had worked my way back up to where I might see or be seen, I hunkered down, moving slowly, humped over like I was a quadruped myself, and stopping to glass regularly before moving on. I kept it up until I saw an ear flick, and then I went into ultra-stealth mode, slowly crawling closer, still using binoculars to see through the tree trunks and branches.

He was an excellent buck—and I still remember that rack— but he was bedded down in the shade of a cedar and there were does and a couple spike bucks nibbling and gossiping right in front of him. There was no shot, but the kiddies and their moms were oblivious to me, so I inched—I millimetered—closer and closer until I got within touching distance of a doe.

Then I got arrogant. I reached out with the barrel of my rifle and touched a doe’s back leg. She jumped and spun around, and clearly had no idea what had touched her or that I was even there, but she knew something wasn’t right and she started stomping and snorting, and that was all it took. The buck got up, not in alarm, really, but with the air of a buck who has decided it’s time to move on to other places and other activities, and the whole herd ambled off before I could get a shot.

So the trophy on my wall was a conciliation buck I took on the last day, unexceptional, but perfectly nice, and looking at him reminds me of the missed trophy of a lifetime and an almost perfect stalk.

Another hunt with my old friend Gerald McRaney, this time in his home state of Mississippi, where he plied me with so much bourbon I was barely able to hold a rifle the next morning, let alone shoot it. He is a bad man, devoid of conscience or principles, and it is only because of my saint-like patience and forbearance that I put up with him.

We were hunting on private land and on the last day I was sitting in a stand with the landowner. I had given up any thought of taking a trophy, and the landowner and I were looking at a group of fat young does, discussing—not loudly, but not whispering either—which doe I should take for the meat, when a huge buck walked directly under our stand, literally between the metal legs of the box.

My first thought was that he was the village idiot. My second thought was that while he was still a dandy, he would have been a state record if I had seen him three or four years earlier. The rack was still heavy, but it was made wide by time and gravity, and it had degenerated from points to crab claws. His spine was clearly visible and so swayed that he looked almost like a geriatric horse. When we examined him after the shot, the few teeth he had were worn down to the gums.

I suspect the reason he walked so very close without hearing us was because he was deaf, but every time I look at that trophy, I remind myself never to drink bourbon with Mack again.

So many others. A whitetail taken on Frank Lyons’ beloved and legendary Wingmead Plantation, so symmetrical it looks as if it had been digitally created for a movie about whitetail. A Coues deer taken in the mountains of Sonora, Mexico, just before that particular area became too popular with drug cartels to be safely hunted. A mountain lion taken in the Chiricahua range with the living legend Warner Glenn. A bear shot in self-defense while hunting with my long-time dentist, friend and hunting partner Dave Markiewitz, who was later murdered by a survivalist lunatic, sparking the longest and most extensive manhunt in Kern County history.

So many others, so many others. The trophies are nice, but memories shine no matter what color the wall is painted.

This book is a collection of the author’s true-shared essays of outdoor activities and of the folks he has encountered on the Great High Plains. It’s Ben’s Rocky Mountain Memories of hunting, fishing, people and places. This book has a far wider appeal than just for the hunting and fishing audience. No matter where you live, or what age, or in what walk of life you live, one of these essays will revive your memory of an experience in some way you had or someone in your family has handed down to you.

This book is a collection of the author’s true-shared essays of outdoor activities and of the folks he has encountered on the Great High Plains. It’s Ben’s Rocky Mountain Memories of hunting, fishing, people and places. This book has a far wider appeal than just for the hunting and fishing audience. No matter where you live, or what age, or in what walk of life you live, one of these essays will revive your memory of an experience in some way you had or someone in your family has handed down to you.

The stories are all vintage Ben; his writing is honest, heartfelt, always intends to be instructive, and is simply fun to read. They are not about killing things or hook and bullet stuff. These essays are about appreciating the land, enjoying the chase with his bird dogs, fly-fishing, conversations with outdoor folks and kicking gravel with landowners. Then, after each one of Ben’s stories there is a vignette, written by one of his many outdoor friends. Best Day Yet is an attitude that Ben created for himself. It’s how he feels about things according to his sense of the world around him. It’s like sitting by a mountain lake after a wonderful day of fishing with a flask of cheap blended scotch whiskey and believing an airplane dropped a fine 30-year-old single malt scotch whiskey that just drifted to shore at the exact spot where he was camping. His partner sitting next to him says, “What do you think of the whiskey?” “That’s one fine scotch.” Buy Now